Posts Tagged ‘Trust-based approach’

When it’s Time to Make a Difference

When it’s time to make meaningful change, there’s no time for consensus.

When the worn path of success must be violated, use a small team.

When it’s time for new thinking, create an unreasonable deadline, and get out of the way.

The best people don’t want the credit, they want to be stretched just short of their breaking point.

When company leadership wants you to build consensus before moving forward, they don’t think the problem is all that important or they don’t trust you.

When it’s time to make unrealistic progress, it’s time for fierce decision making.

When there’s no time for consensus, people’s feelings will be hurt. But there’s no time for that either.

When you’re pissed off because there’s been no progress for three years, do it yourself.

When it’s time to make a difference, permission is not required. Make a difference.

The best people must be given the responsibility to use their judgment.

When it’s time to break the rules, break them.

When the wheels fall off, regardless of the consequences, put them back on.

When you turn no into yes and catch hell for violating protocol, you’re working for the wrong company.

When everyone else has failed, it’s time to use your discretion and do as you see fit.

When you ask the team to make rain and they balk, you didn’t build the right team.

When it’s important and everyone’s afraid of getting it wrong, do it yourself and give them the credit.

The best people crave ridiculous challenges.

When the work must be different, create an environment that demands the team acts differently.

When it’s time for magic, keep the scope tight and the timeline tighter.

When the situation is dire and you use your discretion, to hell with anyone who has a problem with it.

When it’s time to pull a rabbit out of the hat, you get to decide what gets done and your special team member gets to decide how to go about it. Oh, and you also get to set an unreasonable time constraint.

When it’s important, to hell with efficiency. All that matters is effectiveness.

The best people want you to push them to the limit.

When you think you might get fired for making a difference, why the hell would you want to work for a company like that?

When it’s time to disrespect the successful business model, it’s time to create harsh conditions that leave the team no alternative.

The best people want to live where they want to live and do impossible work.

Image credit — Bernard Spragg. Nz

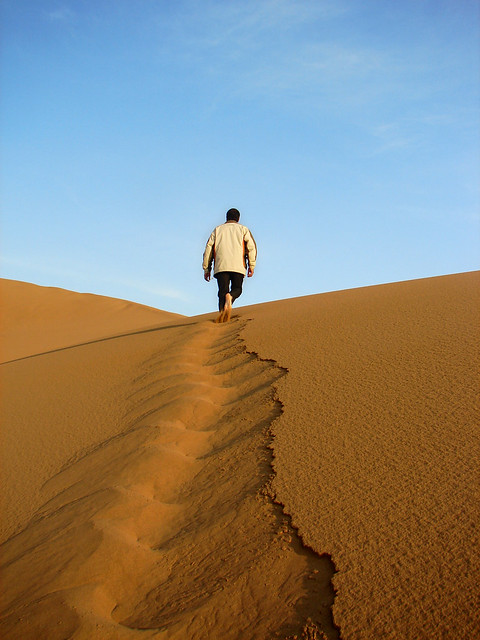

The Most Important People in Your Company

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

The most important person in your company is the person that drags the most important projects over the finish line. Full stop.

When the project is on the line, the CEO doesn’t matter; the General Manager doesn’t matter; the Business Leader doesn’t matter. The person that matters most is the Project Manager. And the second and third most important people are the two people that the Project Manager relies on.

Don’t believe that? Well, take a bite of this. If the project fails, the product doesn’t sell. And if the product doesn’t sell, the revenue doesn’t come. And if the revenue doesn’t come, it’s game over. Regardless of how hard the CEO pulls, the product doesn’t launch, the revenue doesn’t come, and the company dies. Regardless of how angry the GM gets, without a product launch, there’s no revenue, and it’s lights out. And regardless of the Business Leader’s cajoling, the project doesn’t cross the finish line unless the Project Manager makes it happen.

The CEO can’t launch the product. The GM can’t launch the product. The Business Leader can’t launch the product. Stop for a minute and let that sink in. Now, go back to those three sentences and read them out loud. No, really, read them out loud. I’ll wait.

When the wheels fall off a project, the CEO can’t put them back on. Only a special Project Manager can do that.

There are tools for project management, there are degrees in project management, and there are certifications for project management. But all that is meaningless because project management is alchemy.

Degrees don’t matter. What matters is that you’ve taken over a poorly run project, turned it on its head, and dragged it across the line. What matters is you’ve run a project that was poorly defined, poorly staffed, and poorly funded and brought it home kicking and screaming. What matters is you’ve landed a project successfully when two of three engines were on fire. (Belly landings count.) What matters is that you vehemently dismiss the continuous improvement community on the grounds there can be no best practice for a project that creates something that’s new to the world. What matters is that you can feel the critical path in your chest. What matters is that you’ve sprinted toward the scariest projects and people followed you. And what matters most is they’ll follow you again.

Project Managers have won the hearts and minds of the project team.

The Project manager knows what the team needs and provides it before the team needs it. And when an unplanned need arises, like it always does, the project manager begs, borrows, and steals to secure what the team needs. And when they can’t get what’s needed, they apologize to the team, re-plan the project, reset the completion date, and deliver the bad news to those that don’t want to hear it.

If the General Manager says the project will be done in three months and the Project Manager thinks otherwise, put your money on the Project Manager.

Project Managers aren’t at the top of the org chart, but we punch above our weight. We’ve earned the trust and respect of most everyone. We aren’t liked by everyone, but we’re trusted by all. And we’re not always understood, but everyone knows our intentions are good. And when we ask for help, people drop what they’re doing and pitch in. In fact, they line up to help. They line up because we’ve gone out of our way to help them over the last decade. And they line up to help because we’ve put it on the table.

Whether it’s IoT, Digital Strategy, Industry 4.0, top-line growth, recurring revenue, new business models, or happier customers, it’s all about the projects. None of this is possible without projects. And the keystone of successful projects? You guessed it. Project Managers.

Image credit – Bernard Spragg .NZ

When It’s Time to Defy Gravity

If you pull hard on your team, what will they do? Will they rebel? Will they push back? Will they disagree? Will they debate? And after all that, will they pull with you? Will the pull for three weeks straight? Will they pull with their whole selves? How do you feel about that?

If you pull hard on your team, what will they do? Will they rebel? Will they push back? Will they disagree? Will they debate? And after all that, will they pull with you? Will the pull for three weeks straight? Will they pull with their whole selves? How do you feel about that?

If you pull hard on your peers, what will they do? Will they engage? Will they even listen? Will they dismiss? And if they dismiss, will you persist? Will you pull harder? And when you pull harder, do they think more of you? And when you pull harder still, do they think even more of you? Do you know what they’ll do? And how do you feel about that?

If you push hard on your leadership, what will they do? Will they ‘lllisten or dismiss? And if they dismiss, will you push harder? When you push like hell, do they like that or do they become uncomfortable, what will you do? Will they dislike it and they become comfortable and thankful you pushed? Whatever they feel, that’s on them. Do you believe that? If not, how do you feel about that?

When you say something heretical, does your team cheer or pelt you with fruit? Do they hang their heads or do they hope you do it again? Whatever they do, they’ve watched your behavior for several years and will influence their actions.

When you openly disagree with the company line, do your peers cringe or ask why you disagree? Do they dismiss your position or do they engage in a discussion? Do they want this from you? Do they expect this from you? Do they hope you’ll disagree when you think it’s time? Whatever they do, will you persist? And how do you feel about that?

When you object to the new strategy, does your leadership listen? Or do they un-invite you to the next strategy session? And if they do, do you show up anyway? Or do they think you’re trying to sharpen the strategy? Do they think you want the best for the company? Do they know you’re objecting because everyone else in the room is afraid to? What they think of your dissent doesn’t matter. What matters is your principled behavior over the last decade.

If there’s a fire, does your team hope you’ll run toward the flames? Or, do they know you will?

If there’s a huge problem that everyone is afraid to talk about, do your peers expect you get right to the heart of it? Or, do they hope you will? Or, do they know you will?

If it’s time to defy gravity, do they know you’re the person to call?

And how do you feel about that?

Image credit – The Western Sky

The Giving Cycle

The best gifts are the ones that demonstrate to the recipients that you understand them. You understand what they want; you understand their size (I’m and men’s large); you understand their favorite color; you know what they already have; you know what they’re missing, and you know what they need.

The best gifts are the ones that demonstrate to the recipients that you understand them. You understand what they want; you understand their size (I’m and men’s large); you understand their favorite color; you know what they already have; you know what they’re missing, and you know what they need.

On birthdays and holidays, everyone knows it’s time to give gifts and this makes it easy for us to know them for what they are. And, just to make sure everyone knows the gift is a gift, we wrap them in colorful paper or place them in a fancy basket and formally present them. But gifts given at work are different.

Work isn’t about birthdays and holidays, it’s about the work. There’s no fixed day or date to give them. And there’s no expectation that gifts are supposed to be given. And gifts given at work are not the type that can be wrapped in colorful paper. In that way, gifts given at work are rare. And when they are given, often they’re not recognized as gifts.

The gift of a challenge. When you give someone a challenge, that’s a gift. Yes, the task is difficult. Yes, the request is unreasonable. Yes, it’s something they’ve never done before. And, yes, you believe they’re up to the challenge. And, yes, you’re telling them they’re worthy of the work. And whether the complete 100% of the challenge or only 5% of it, you praise them. You tell them, Holy sh*t! That was amazing. I gave you an impossible task and you took it on. Most people wouldn’t have even tried and you put your whole self into it. You gave it a go. Wow. I hope you’re proud of what you did because I am. The trick for the giver is to praise.

The gift of support. When you support someone that shouldn’t need it, that’s a gift. When the work is clearly within a person’s responsibility and the situation temporarily outgrows them, and you give them what they need, that’s a gift. Yes, it’s their responsibility. Yes, they should be able to handle it. And, yes, you recognize the support they need. Yes, you give them support in a veiled way so that others don’t recognize the gift-giving. And, yes, you do it in a way that the receiver doesn’t have to acknowledge the support and they can save face. The trick for the giver is to give without leaving fingerprints.

The gift of level 2 support. When you give the gift of support defined above and the gift is left unopened, it’s time to give the gift of level 2 support. Yes, you did what you could to signal you left a gift on their doorstep. Yes, they should have seen it for what it was. And, yes, it’s time to send a level 2 gift to their boss in the form of an email sent in confidence. Tell their boss what you tried to do and why you tried to do it. And tell them the guidance you tried to give. This one is called level 2 giving because two people get gifts and because it’s higher-level giving. The trick for the giver is to give in confidence and leave no fingerprints.

The gift of truth. When you give someone the truth of the situation when you know they don’t want to hear it, that’s a gift. Yes, they misunderstand the situation. Yes, it’s their responsibility to understand it. Yes, they don’t want your gift of truth. And, yes, you give it to them because they’re off-track. Yes, you give it to them because you care about them. And, yes you give the gift respectfully and privately. You don’t give a take-it-or-leave-it ultimatum. And you don’t make the decision for them. You tell them why you see it differently and tell them you hope they see your gift as it was intended – as a gift. The trick for the giver is to give respectfully and be okay whether the gift is opened or not.

The gift of forgiveness. When someone has mistreated you or hurt you, and you help them anyway, that’s a gift. Yes, they need help. Yes, the pain is still there. And, yes, you help them anyway. They hurt you because of the causes and conditions of their situation. It wasn’t personal. They would have treated anyone that way. And, yes, this is the most difficult gift to give. And that’s why it’s last on the list. And the trick for the giver is to feel the hurt and give anyway. It will help the hurt go away.

It may not seem this way, but the gifts are for the giver. Givers grow by giving. And best of all for the givers, they get to watch as their gifts grow getters into givers. And that’s magical. And that brings joy.

And the giving cycle spirals on.

Image credit – KTIQS.LCV

A Recipe to Grow Talent

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it with them, and let them hose it up. Let them do the work they know how to do, you do all the new work except for one new element, and let them do that one bit of new work. They won’t know how to do it, and they’ll get it wrong. And you’ve got to let them. Pretend you’re not paying attention so they think they’re doing it on their own, but pay deep attention. Know what they’re going to do before they do it, and protect them from catastrophic failure. Let them fail safely. And when then hose it up, explain how you’d do it differently and why you’d do it that way. Then, let them do it with your help. Praise them for taking on the new work. Praise them for trying. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help them when they need it. Let them lead the project, but stay close to the work. Pretend to be busy doing another project, but stay one step ahead of them. Know what they plan to do before they do it. If they’re on the right track, leave them alone. If they’re going to make a small mistake, let them. And be there to pick up the pieces. If they’re going to make a big mistake, casually check in with them and ask about the project. And, with a light touch, explain why this situation is different than it seems. Help them take a different approach and avoid the big mistake. Praise them for their good work. Praise them for their professionalism. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help only when they ask. Take off the training wheels and let them run the project on their own. Work on something else, and don’t keep track of their work. And when they ask for help, drop what you are doing and run to help them. Don’t walk. Run. Help them like they’re your family. Praise them for doing the work on their own. Praise them for asking for help. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do the new work for them, then repeat. Repeat the whole recipe for the next level of new work you’ll help them master.

Image credit — John Flannery

When Problems Are Bigger Than They Seem

If words and actions are different, believe the actions.

If the words change over time, don’t put stock in the person delivering them.

If a good friend doesn’t trust someone, neither should you.

If the people above you don’t hold themselves accountable, yet they try to hold you accountable, shame on them.

If people are afraid to report injustices, it’s just a matter of time before the best people leave.

If actions are consistently different than the published values, it’s likely the values should be up-revved.

If you don’t trust your leader, respect your instincts.

If people are bored and their boredom is ignored, expect the company to death spiral into the ground.

If behaviors are different than the culture, the culture isn’t the culture.

If all the people in a group apply for positions outside the group, the group has a problem.

When actions seen by your eyes are different than the rhetoric force-fed into your ears, believe your eyes.

If you think your emotional wellbeing is in jeopardy, it is.

If to preserve your mental health you must hunker down with a trusted friend, find a new place to work.

If people are afraid to report injustices, company leadership has failed.

If the real problems aren’t discussed because they’re too icky, there’s a bigger problem.

If everyone in the group applies for positions outside the group and HR doesn’t intervene, the group isn’t the problem.

And to counter all this nonsense:

If someone needs help, help them.

If someone helps you, thank them.

If someone does a good job, tell them.

Rinse, and repeat.

Without trust, there is nothing.

If someone treats you badly, that’s on them. You did nothing wrong.

If someone treats you badly, that’s on them. You did nothing wrong.

When you do your best and your boss tells you otherwise, your boss is unskillful.

If you make a mistake, own it. And if someone gives you crap about it, disown them.

If someone is untruthful, hold them accountable. If they’re still untruthful, double down and hold them accountable times two.

If you’re treated unfairly, it’s because someone has low self-esteem. And if you get mad at them, it’s because you have low self-esteem.

What people think about you is none of your concern, especially if they treat you badly.

If you see something, say something, especially when you see a leader treat their team badly.

A leader that treats you badly isn’t a leader.

If you don’t trust your leader, find a new leader. And if you can’t find a new leader to trust, find a new company.

If someone belittles you, that’s about them. Try to forgive them. And if you can’t, try again.

No one deserves to be treated badly, even if they treat you badly.

If you have high expectations for your leader and they fall short, that says nothing about your expectations.

If someone’s behavior makes you angry, that’s about you. And when your behavior makes someone angry, the calculus is the same.

When actions are different from the words, believe the actions.

When the words are different than the actions, there can be no trust.

The best work is built on trust. And without trust, the work will not be the best.

If you don’t feel comfortable calling people on their behavior it’s because you don’t believe they’ll respond in good faith.

If you don’t think someone is truthful, nothing good will come from working with them.

If you can’t be truthful it’s because there is insufficient trust.

Without trust there is nothing.

If there’s a mismatch between someone’s words and their actions, call them on their actions.

If you call someone on their actions and they use their words to try to justify their actions, run away.

You might be a leader if…

If you have to tell people what to do, you didn’t teach them to think for themselves.

If you have to tell people what to do, you didn’t teach them to think for themselves.

If you know one of your team members has something to say but they don’t say it, it’s because you didn’t create an environment where they feel safe.

If your new hire doesn’t lead an important part of a project within the first week, you did them a disservice.

If the team learns the same thing three times, you should have stepped in two times ago.

If you don’t demand that your team uses their discretion, they won’t.

If the project’s definition of success doesn’t correlate with business success, you should have asked for a better definition of success before the project started.

If someone on your team tells you you’re full of sh*t, thank them for their truthfulness.

If your team asks for permission, change how you lead them.

If you can’t imagine that one of your new hires will be able to do your job in five years, you hired the wrong people.

If your team doesn’t disagree with you, it’s because you haven’t led from your authentic self.

If your team doesn’t believe in themselves, neither do you.

If your team disobeys your direct order, thank them for disobeying and apologize for giving them an order.

If you ask a new hire to lead an important part of a project and you don’t meet with them daily to help them, you did them a disservice.

If one of your team members moves to another team and their new leader calls them “unmanageable”, congratulations.

If your team knows what you’ll say before they ask you, you’ve led them from your authentic self.

If you haven’t chastised your team members for their lack of disagreement with you, you should.

If you don’t tell people they did a good job, they won’t.

Image credit — Hamed Saber

People, Money and Time

If you want the next job, figure out why.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting the job you have.

When you don’t care about the next job it’s because you fit the one you have.

A larger salary is good, but time with family is better.

Less time with family is a downward spiral into sadness.

When you decide you have enough, you don’t need things to be different.

A sense of belonging lasts longer than a big bonus.

A cohesive team is an oasis.

Who you work with makes all the difference.

More stress leads to less sleep and that leads to more stress.

If you’re not sleeping well, something’s wrong.

How much sleep do you get? How do you feel about that?

Leaders lead people.

Helping others grow IS leadership.

Every business is in the people business.

To create trust, treat people like they matter. It’s that simple.

When you do something for someone even though it comes at your own expense, they remember.

You know you’ve earned trust when your authority trumps the org chart.

Image credit — Jimmy Baikovicius

The Difficulty of Commercializing New Concepts

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you have the data that says the market for the new concept is big enough, you waited too long.

If you require the data that verifies the market is big enough before pursuing new concepts, you’ll never pursue them.

If you’re afraid to trust the judgement of your best technologists, you’ll never build the traction needed to launch new concepts.

If you will sell the new concept to the same old customers, don’t bother. You already sold them all the important new concepts. The returns have already diminished.

If you must sell the new concept to new customers, it could create a whole new business for you.

If you ask your successful business units to create and commercialize new concepts, they’ll launch what they did last time and declare it a new concept.

If you leave it to your successful business units to decide if it’s right to commercialize a new concept created by someone else, they won’t.

If a new concept is so significant that it will dwarf the most successful business unit, the most successful business unit will scuttle it.

If the new concept is so significant it warrants a whole new business unit, you won’t make the investment because the sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept are yet to be realized.

If you can’t justify the investment to commercialize a new concept because there are no sales of the yet-to-be-launched concept, you don’t understand that sales come only after you launch. But, you’re not alone.

If a new concept makes perfect sense, you would have commercialized it years ago.

If the new concept isn’t ridiculed by the Status Quo, do something else.

If the new concept hasn’t failed three times, it’s not a worthwhile concept.

If you think the new concept will be used as you intend, think again.

If you’re sure a new concept will be a flop, you shouldn’t be. Same goes for the ones you’re sure will be successful.

If you’re afraid to trust your judgement, you aren’t the right person to commercialize new concepts.

And if you’re not willing to put your reputation on the line, let someone else commercialize the new concept.

Image credit – Melissa O’Donohue

As a leader, be truthful and forthcoming.

Have you ever felt like you weren’t getting the truth from your leader? You know – when they say something and you know that’s not what they really think. Or, when they share their truth but you can sense that they’re sharing only part of the truth and withholding the real nugget of the truth? We really have no control over the level of forthcoming of our leaders, but we do have control over how we respond to their incomplete disclosure.

There are times when leaders cannot, by law, disclose things. But, even then, they can make things clear without disclosing what legally cannot be disclosed. For example, they can say: “That’s a good question and it gets to the heart of the situation. But, by law, I cannot answer that question.” They did not answer the question, but they did. They let you know that you understand the situation; they let you know that there is an answer; and the let you know why they cannot share it with you. As the recipient of that non-answer answer, I respect that leader.

There are also times when a leader withholds information or gives a strategically partial response for inappropriate reasons. When a leader withholds information to manipulate or control, that’s inappropriate. It’s also bad leadership. When a leader withholds information from their smartest team members, they lose trust. And when leaders lose trust, the best people are crestfallen and withhold their best work. The thinking goes like this. If my leader doesn’t trust me enough to share the complete set of information with me it’s because they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust and they don’t think highly of me. And if they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust, they don’t understand who I am and what I stand for. And if they don’t understand me and know what I stand for, they’re not worthy of my best work.

As a leader, you must share all you can. And when you can’t, you must tell your team there are things you can’t share and tell them the reasons why. Your team can handle the fact that there are some things you cannot share. But what your team cannot hand is when you withhold information so you can gain the upper hand on them. And your team can tell when you’re withholding with your best interest in mind. Remember, you hired them because they were smart, and their smartness doesn’t go away just because you want to control them.

If your direct reports always tell you they can get it done even when they don’t have the capacity and capability, that’s not the behavior you want. If your direct reports tell you they can’t get it done when they can’t get it done, that’s the behavior you want. But, as a leader, which behavior do you reward? Do you thank the truthful leader for being truthful about the reality of insufficient resources and do you chastise the other leader for telling you what you want to hear? Or, do you tell the truthful leader they’re not a team player because team players get it done and praise the unjustified can-do attitude of the “yes man” leader? As a leader, I suggest you think deeply about this. As a direct report of a leader, I can tell you I’ve been punished for responding in way that was in line with the reality of the resources available to do the work. And I can also tell you that I lost all respect for that leader.

As a leader, you have three types of direct reports. Type I are folks are happy where they are and will do as little as possible to keep it that way. Type II are people that are striving for the next promotion and will tell you whatever you want to hear in order to get the next job. Type III are the non-striving people who will tell you what you need to hear despite the implications to their career. Type I people are good to have on your team. They know what they can do and will tell you when the work is beyond their capability. Type II people are dangerous because they think only of themselves. They will hang you out to dry if they think it will advance their career. And Type III people are priceless.

Type III people care enough to protect you. When you ask them for something that can’t be done, they care enough about you to tell you the truth. It’s not that they don’t want to get it done, they know they cannot. And they’re willing to tell you to your face. Type II people don’t care about you as a leader; they only care about themselves. They say yes when they know the answer is no. And they do it in a way that absolves them of responsibility when the wheels fall off. As a leader, which type do you want on your team? And as a leader, which type do you promote and which do you chastise. And, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you must be truthful. And when you can’t disclose the full truth, tell people. And when your Type II direct reports give you the answer they know you want to hear, call them on their bullshit. And when your Type III folks give you the answer they know you don’t want to hear, thank them.

Image credit — Anandajoti Bhikkhu

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski