Posts Tagged ‘Manufacturing Competitveness’

Continuous Improvement Is Dead

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time, just three percent better, so none of your people can try new things.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time, just three percent better, so none of your people can try new things.

Discontinuous Improvement – Make a radical step-change in performance at the expense of continuously improving it.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so you can say “no” to projects that are magical.

No-To-Yes – Make the product do something it cannot. That way you can sell a new value proposition to new customers and new markets. And you can threaten those that are clinging to your tired value proposition.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so no one will be threatened by meaningful change.

Less With Far Less – Reduce the goodness of today’s offering to free up design space and create an entirely new offering that provides 80% of the goodness at 20% of the price. That way, you can sell a whole new family of offerings to customers that cannot buy today’s offering.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so we can rest on our laurels.

Obsolete Your Best Work – Design and commercialize new offerings that purposefully make obsolete your most profitable offering. This requires level 5 courage.

And how do you do all this? Mobilize the Trust Network.

“fear — may 9 (day 9)” by theogeo is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Sometimes too much is just that – too much.

When your best isn’t good enough, how do you feel? When your best isn’t good enough, what do you do? But more importantly, when your best isn’t good enough, what does that say about you?

When your best isn’t good enough, how do you feel? When your best isn’t good enough, what do you do? But more importantly, when your best isn’t good enough, what does that say about you?

If your best used to be good enough and now it isn’t, there are four possible explanations. 1.) Expectations increased and your performance is unchanged. 2.) Expectations increased and your performance increased less. 3.) Expectations increased and your performance decreased.

If expectations of your performance haven’t increased over last year, I want to work where you work because your company is an oasis (and an aberration). Since nearly all industries and occupations are governed by the unnatural mindset of growth-year-on-year-no-matter-what, it’s highly likely your performance expectations have increased. There’s no need to review this scenario.

In scenario one, your performance is unchanged. Why? Well, you may have tried to increase your performance but issues unrelated to work have consumed huge amounts of your emotional energy, and this new drain on your emotional energy consumed the energy you needed to increase your performance. A list of such issues includes global warming, deforestation, plastic in our water supply, COVID, political unrest, and the regular issues such as medical care for aging parents, death of your parents, inevitable health issues related to your aging. What does that say about you?

In scenario two, your performance increased, but the increase was insufficient. Maybe your performance would have increased quite a bit, but the special cause issues (COVID, etc.) along with the common cause issues (you and your parents get older every year) impacted your performance in a way that lessened the increase in your performance. Without the special causes, you would have met the increased expectations, but because of them, you did not. What does that say about you?

In scenario three, even though expectations increased, your performance decreased. In this case, it could be that political unrest and the other special causes teamed up with the common causes (stress of everyday life) to reduce your performance. What does that say about you?

In thermodynamics, there’s a law whose implications make it certain that there’s a limit to the amount of matter (stuff) you can put in a control volume (a defined volume that has a limit). That means that if every year you add air to a balloon, eventually it pops. Even the strongest ones. And when you extend this notion to people, it says that no matter how much pressure you apply to people, there’s a limit to what they can achieve. And if you apply pressure that overcomes their physical limit, they pop. Even the strongest ones. Or, maybe, especially the strongest ones because they try to take on more than their share.

People have a physical limit, and people cannot indefinitely support a mindset of growth-every-year-no-matter-what. No matter what, people will pop. It’s not if, it’s when. And add in the special causes of COVID, political unrest, and environmental problems and people pop sooner and cannot do what they did last year, no matter what.

And what does all this say about you? It says you are trying harder than ever. It says you are strong. It says you are amazing.

And what does it say about growth-every-year-no-matter-what? It says we should stop with all that, at least for a while.

Image credit — Judy Schmidt

Are you doing what you did last time?

If there’s no discomfort, there’s no novelty.

When there’s no novelty, it means you did what you did last time.

When you do what you did last time, you don’t grow.

When you do what you did last time, there’s no learning.

When you do what you did last time, opportunity cost eats you.

If there’s no discomfort, you’re not trying hard enough.

If there’s no disagreement, critical thought is in short supply.

When critical thought is in short supply, new ideas never see the light of day.

When new ideas never see the light of day, you end up doing what you did last time.

When you do what you did last time, your best people leave.

When you do what you did last time, your commute into work feels longer than it is.

When you do what you did last time, you’re in a race to the bottom.

If there’s no disagreement, you’re playing a dangerous game.

If there’s no discretionary work, crazy ideas never grow into something more.

When crazy ideas remain just crazy ideas, new design space remains too risky.

When new design space remains too risky, all you can do is what you did last time.

When you do what you did last time, managers rule.

When you do what you did last time, there is no progress.

When you do what you did last time, great talent won’t accept your job offers.

If there’s no discretionary work, you’re in trouble.

We do what we did last time because it worked.

We do what we did last time because we made lots of money.

We do what we did last time because it’s efficient.

We do what we did last time because it feels good.

We do what we did last time because we think we know what we’ll get.

We do what we did last time because that’s what we do.

Doing what we did last time works well, right up until it doesn’t.

When you find yourself doing what you did last time, do something else.

Image credit — Matt Deavenport

The Most Important People in Your Company

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

The most important person in your company is the person that drags the most important projects over the finish line. Full stop.

When the project is on the line, the CEO doesn’t matter; the General Manager doesn’t matter; the Business Leader doesn’t matter. The person that matters most is the Project Manager. And the second and third most important people are the two people that the Project Manager relies on.

Don’t believe that? Well, take a bite of this. If the project fails, the product doesn’t sell. And if the product doesn’t sell, the revenue doesn’t come. And if the revenue doesn’t come, it’s game over. Regardless of how hard the CEO pulls, the product doesn’t launch, the revenue doesn’t come, and the company dies. Regardless of how angry the GM gets, without a product launch, there’s no revenue, and it’s lights out. And regardless of the Business Leader’s cajoling, the project doesn’t cross the finish line unless the Project Manager makes it happen.

The CEO can’t launch the product. The GM can’t launch the product. The Business Leader can’t launch the product. Stop for a minute and let that sink in. Now, go back to those three sentences and read them out loud. No, really, read them out loud. I’ll wait.

When the wheels fall off a project, the CEO can’t put them back on. Only a special Project Manager can do that.

There are tools for project management, there are degrees in project management, and there are certifications for project management. But all that is meaningless because project management is alchemy.

Degrees don’t matter. What matters is that you’ve taken over a poorly run project, turned it on its head, and dragged it across the line. What matters is you’ve run a project that was poorly defined, poorly staffed, and poorly funded and brought it home kicking and screaming. What matters is you’ve landed a project successfully when two of three engines were on fire. (Belly landings count.) What matters is that you vehemently dismiss the continuous improvement community on the grounds there can be no best practice for a project that creates something that’s new to the world. What matters is that you can feel the critical path in your chest. What matters is that you’ve sprinted toward the scariest projects and people followed you. And what matters most is they’ll follow you again.

Project Managers have won the hearts and minds of the project team.

The Project manager knows what the team needs and provides it before the team needs it. And when an unplanned need arises, like it always does, the project manager begs, borrows, and steals to secure what the team needs. And when they can’t get what’s needed, they apologize to the team, re-plan the project, reset the completion date, and deliver the bad news to those that don’t want to hear it.

If the General Manager says the project will be done in three months and the Project Manager thinks otherwise, put your money on the Project Manager.

Project Managers aren’t at the top of the org chart, but we punch above our weight. We’ve earned the trust and respect of most everyone. We aren’t liked by everyone, but we’re trusted by all. And we’re not always understood, but everyone knows our intentions are good. And when we ask for help, people drop what they’re doing and pitch in. In fact, they line up to help. They line up because we’ve gone out of our way to help them over the last decade. And they line up to help because we’ve put it on the table.

Whether it’s IoT, Digital Strategy, Industry 4.0, top-line growth, recurring revenue, new business models, or happier customers, it’s all about the projects. None of this is possible without projects. And the keystone of successful projects? You guessed it. Project Managers.

Image credit – Bernard Spragg .NZ

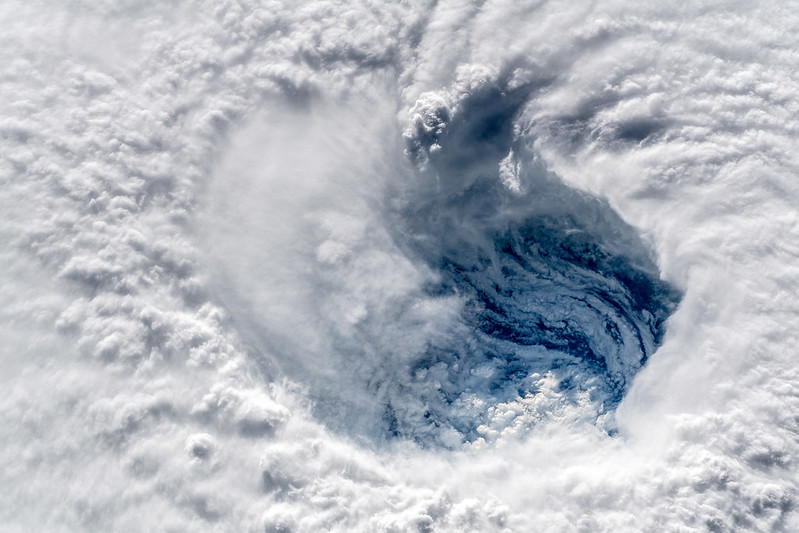

Companies, Acquisitions, Startups, and Hurricanes

If you run a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. You can’t control how the people in your company will respond to input, but you can choose the projects they work on. You can’t control which features and functions your customers will like, but you can choose which features and functions become part of the next product. And you can’t control if a new technology will work, but you can choose the design space to investigate. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to buy a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. In this case, the resources are your hard-earned money and your choice is which company to buy. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to invest in a startup company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. This case is the same as the previous one – your money is the resource and the company you choose defines how you allocate your resources. This one is a little different in that the uncertainty is greater, but so is the potential reward. Again, the same open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

Taking a step back, the three scenarios can be generalized into a category called a “system.” And the question becomes – how to understand the system in a way that improves resource allocation and increases your probability of success?

These people systems aren’t predictable in an if-A-then-B way. But they do have personalities or dispositions. They’ve got characteristics similar to hurricanes. A hurricane’s exact path cannot be forecasted, the meteorologist can use history and environmental conditions to broadly define regions where the probability of danger is higher. The meteorologist continually monitors the current state of the hurricane (the system as it is) and tracks its position over time to get an idea of its trajectory (a system’s momentum). The key to understanding where the hurricane could go next: where it is right now (current state), how it got there (how it has behaved over time), and how have other hurricanes tracked under similar conditions (its disposition). And it’s the same for systems.

To improve your understanding of how your system may respond, understand it as it is. Define the elements and how those elements interact. Then, work backward in time to understand previous generations of the system. Which elements were improved? Which ones were added? Then, like the meteorologist, start at the system’s genesis and move forward to the present to understand its path. Use the knowledge of its path and the knowledge of systems (it’s important to be the one that improves the immature elements of the system and systems follow S-curves until the S-curve flattens) to broadly define regions where the probability of success is higher.

These methods won’t guarantee success. But, they will help you choose projects, choose acquisitions, choose technologies, and choose startups in a way that increases your probability of success.

Image credit — Alexander Gerst

An Environmental Call-To-Arms for Industry

What is your obligation to improve the health of our planet?

What is your obligation to improve the health of our planet?

For the CEO – Look around. Look at Europe. Look at China’s plans. Look at the startups. I know you want to achieve your growth objectives, but if you don’t take seriously the race toward cleaner products and services, you’ll go out of business. You can see this as a problem or an opportunity. Bury your head or put on your track shoes and run! It’s your choice.

Look at the oceans. Look at the landfills. Look at the rise in global temperatures. Just look. This isn’t about ROI, this is about survival. Growth objectives aside, no one will buy things when they are struggling to survive in an uncertain future. Your same old dirty products won’t cut it anymore. So, what are you going to do?

For an example of a path forward, look to the companies in the oil business. Their recipe is clear. They’ve got to use their large but ever-diminishing profits to buy themselves into technologies and industries that will ultimately eat their core business. Though the timing is uncertain, it’s certain that improvements in cleaner technologies will demand they make the change.

Whatever you do, don’t wait. You don’t have much time. Cleaner technologies are getting better every day. It’s time to start.

For Marketing – Look at the upstarts. Look at the powerful companies in adjacent markets who will soon be your direct competitors. Look at your stodgy, unprofitable competitors who are now sufficiently desperate to try anything. Their next marketing push will be built on the bedrock of an improved planet. They’ll be almost as good as you in the traditional areas of productivity and quality and they’ll blow your doors off with their meaner and greener products. Customers will choose green over brown. And they’ll look for real improvements that make the planet smile. The time for green-washing is past. That trick is out of gas.

You need to help customers with new jobs to be done. They care about their environment. They care about their carbon footprint. They care about clean water. And they care about recycling and reuse. It’s real. They care. Now it’s up to you to help them make progress in these areas. It will be a tough road to convince your company that things need to change, but that’s why you’re in Marketing.

You’re already behind. It’s time to start. And it’s up to you to lead the charge.

For Manufacturing – Look at your Value Stream Maps (VSMs). Assign a carbon footprint to each link in the chain. And do the same with water consumption. Assess each process step for carbon and water and rank them worst to best. For the worst, run carbon kaizens and improve the carbon footprint. And run water kaizens for the thirstiest processes.

And look again at your VSMs, and look more broadly. Look back into the supply chain, rank for carbon and water and improve the ones that need the treatment. And teach your suppliers how to do it. And look forward into your distribution channels and improve or eliminate the worst actors. And then propose to Marketing that you teach your customers how to use VSMs to clean up their act. And challenge Engineering to change the design to eliminate the remaining bad actors.

You’ve made good progress with your value streams. Now it’s time to help others make the progress that must be made. As subject matter experts, it’s your time to shine. And, please, start now.

For Engineering – Look at your products. Look at how they’re used. Look at how they’re delivered. Look at how they’re made. Look at how they’re recycled. Sure, your products provide good functionality, but throughout their life cycle they also create carbon dioxide and consume water. And you’re the only ones that can design out the environmental impact.

Learn how to do a Life Cycle Assessment (LCA). Learn which elements of the product create the largest problems. For all the parts that make up the product, sort them worst to best to prioritize the design work. It’s time for radical part count reduction. Try to design out half the parts. It’s possible. And the payoff is staggering. What’s the carbon footprint of a part that was designed out of the product?

Or, to make a more radical improvement, consider an Innovation Burst Event (IBE) to make a fundamental change in the way your products/services impact the environment. With this approach, your innovation work, by definition, will make the planet smile.

It’s time to be open-minded. Ask Manufacturing for the worst processes (including supply chain and distribution) and try to design them out. Design out the part, or change the material, or change the design to enable a friendlier process. Manufacturing can only improve a bad process, but you can design them out altogether. There’s power in that, but with power comes responsibility.

And it’s time for you to take responsibility.

For Everyone in Industry – Regardless of your company, your country or your political affiliation, we can all agree that all our lives get better as the health of our planet improves. And everyone can agree that cleaner air is better. And everyone can agree it’s the same for our water – cleaner is better. And that’s a whole lot of agreement.

As industry leaders, I challenge you to build on that common ground. As industry leaders, I challenge you to improve our planet one product at a time and one process at a time. And as industry leaders, I challenge you to help each other. There’s no competitive disadvantage when you help a company outside your industry. And there’s no shame in learning from companies outside your industry. And it’s good for the planet and profits. There’s nothing in the away. It’s time to start.

As an industry leader, if you want to make a difference in the health of our planet, send me an email at mike@shipulski.com and we will help each other.

Image credit – halfrain

Additive Manufacturing’s Holy Grail

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

(Price – Cost) x Volume = Profit

The idea is to sell products for more than the cost to make them and sell a lot of them. It’s an intoxicatingly simple proposition. And as long as you look only at the volume – the number of products sold per year – life is good. Just sell more and profits increase. But for a couple reasons, it’s not that simple. First, volume is a result. Customers buy products only when those products deliver goodness at a reasonable price. And second, volume delivers profit only when the cost is less than the price. And there’s the rub with AM.

Here’s a rule – as volume increases, the cost of AM is increasingly higher than traditional manufacturing. This is doubly bad news for AM. Not only is AM more expensive, its profit disadvantage is particularly troubling at high volumes. Here’s another rule – if you’re looking to AM to reduce the cost of a part, look elsewhere. AM is not a bottom-feeder technology.

If you want to create profits with AM, use it to increase price. Use it to develop products that do more and sell for more. The magic of AM is that it can create novel shapes that cannot be made with traditional technologies. And these novel shapes can create products with increased function that demand a higher price. For example, AM can create parts with internal features like serpentine cooling channels with fine-scale turbulators to remove more heat and enable smaller products or products that weigh less. Lighter automobiles get better fuel mileage and customers will pay more. And parts that reduce automobile weight are more valuable. And real estate under the hood is at a premium, and a smaller part creates room for other parts (more function) or frees up design space for new styling, both of which demand a higher price.

Now, back to cost. There’s one exception to cost rule. AM can reduce total product cost if it is used to eliminate high cost parts or consolidate multiple parts into a single AM part. This is difficult to do, but it can be done. But it takes some non-trivial cost analysis to make the case. And, because the technology is relatively new, there’s some aversion to adopting AM. An AM conversion can require a lot of testing and a significant cost reduction to take the risk and make the change.

To win with AM, think more function AND consolidation. More (or new) function to support a higher price (and increase volume) and reduced cost to increase profit per part. Don’t do one or the other. Do both. That’s what GE did with its AM fuel nozzle in their new aircraft engines. They combined 20 parts into a single unit which weighed 25 percent less than a traditional nozzle and was more than five times as durable. And it reduced fuel consumption (more function, higher price).

AM is well-established in prototyping and becoming more established in low-volume manufacturing. The holy grail for AM – high volume manufacturing – will become a broad reality as engineers learn how to design products to take advantage of AM’s unique ability to make previously un-makeable shapes and learn to design for radical part consolidation.

More function AND radical part consolidation. Do both.

Image credit – Les Haines

The Additive Manufacturing Maturity Model

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

Additive Manufacturing (AM) is technology/product space with ever-increasing performance and an ever-increasing collection of products. There are many different physical principles used to add material and there are a range of part sizes that can be made ranging from micrometers to tens of meters. And there is an ever-increasing collection of materials that can be deposited from water soluble plastics to exotic metals to specialty ceramics.

But AM tools and technologies don’t deliver value on their own. In order to deliver value, companies must deploy AM to solve problems and implement solutions. But where to start? What to do next? And how do you know when you’ve arrived?

To help with your AM journey, below a maturity model for AM. There are eight categories, each with descriptions of increasing levels of maturity. To start, baseline your company in the eight categories and then, once positioned, look to the higher levels of maturity for suggestions on how to move forward.

For a more refined calibration, a formal on-site assessment is available as well as a facilitated process to create and deploy an AM build-out plan. For information on on-site assessment and AM deployment, send me a note at mike@shipulski.com.

Execution

- Specify AM machine – There a many types of AM machines. Learn to choose the right machine.

- Justify AM machine – Define the problem to be solved and the benefit of solving it.

- Budget for AM machine – Find a budget and create a line item.

- Pay for machine – Choose the supplier and payment method – buy it, rent to own, credit card.

- Install machine – Choose location, provide necessary inputs and connectivity

- Create shapes/add material – Choose the right CAD system for the job, make the parts.

- Create support/service systems – Administer the job queue, change the consumables, maintenance.

- Security – Create a system for CAD files and part files to move securely throughout the organization.

- Standardize – Once the first machines are installed, converge on a small set of standard machines.

- Teach/Train – Create training material for running AM machine and creating shapes.

Solution

- Copy/Replace – Download a shape from the web and make a copy or replace a broken part.

- Adapt/Improve – Add a new feature or function, change color, improve performance.

- Create/Learn – Create something new, show your team, show your customers.

- Sell Products/Services – Sell high volume AM-produced products for a profit. (Stretch goal.)

Volume

- Make one part – Make one part and be done with it.

- Make five parts – Make a small number of parts and learn support material is a challenge.

- Make fifty parts – Make more than a handful of parts. Filament runs out, machines clog and jam.

- Make parts with a complete manufacturing system – This topic deserves a post all its own.

Complexity

- Make a single piece – Make one part.

- Make a multi-part assembly – Make multiple parts and fasten them together.

- Make a building block assembly – Make blocks that join to form an assembly larger than the build area.

- Consolidate – Redesign an assembly to consolidate multiple parts into fewer.

- Simplify – Redesign the consolidated assembly to eliminate features and simplify it.

Material

- Plastic – Low temperature plastic, multicolor plastics, high performance plastics.

- Metal – Low melting temperature with low conductivity, higher melting temps, higher conductivity

- Ceramics – common materials with standard binders, crazy materials with crazy binders.

- Hybrid – multiple types of plastics in a single part, multiple metals in one part, custom metal alloy.

- Incompatible materials – Think oil and water.

Scale

- 50 mm – Not too large and not too small. Fits the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 500 mm – Larger than the build area of medium-sized machine.

- 5 m – Requires a large machine or joining multiple parts in a building block way.

- 0.5 mm – Tiny parts, tiny machines, superior motion control and material control.

Organizational Breadth

- Individuals – Early adopters operate in isolation.

- Teams – Teams of early adopters gang together and spread the word.

- Functions – Functional groups band together to advance their trade.

- Supply Chain – Suppliers and customers work together to solve joint problems.

- Business Units – Whole business units spread AM throughout the body of their work.

- Company – Whole company adopts AM and deploys it broadly.

Strategic Importance

- Novelty – Early adopters think it’s cool and learn what AM can do.

- Point Solution – AM solves an important problem.

- Speed – AM speeds up the work.

- Profitability – AM improves profitability.

- Initiative – AM becomes an initiative and benefits are broadly multiplied.

- Competitive Advantage – AM generates growth and delivers on Vital Business Objectives (VBOs).

Image credit – Cheryl

To improve innovation, use fewer words.

Everyone knows innovation is difficult, but there’s no best way to make it easier. And everyone knows there’s plenty of opportunities to make innovation more effective, but, again, there’s no best way. Clearly, there are ways to improve the process, and new tools can help, but the right process improvements depend on the existing process and the specific project. And it’s the same for tools – the next tool depends on the existing toolbox and the new work required by the project. With regard to tools and processes, the right next steps are not universal.

Everyone knows innovation is difficult, but there’s no best way to make it easier. And everyone knows there’s plenty of opportunities to make innovation more effective, but, again, there’s no best way. Clearly, there are ways to improve the process, and new tools can help, but the right process improvements depend on the existing process and the specific project. And it’s the same for tools – the next tool depends on the existing toolbox and the new work required by the project. With regard to tools and processes, the right next steps are not universal.

But with all companies’ innovation processes, there is a common factor – the innovation process is run by people. Regardless of process maturity or completeness, people run the process. And this fundamental cuts across language, geography and company culture. And it cuts across products, services, and business models. Like it or not, innovation is done by people.

At the highest level, innovation converts ideas into something customers value and delivers the value to them for a profit. At the front end, innovation is about ideas, in the middle, it’s about problems and at the back end, it’s about execution. At the front, people have ideas, define them, evaluate them and decide which ones to advance. In the middle, people define the problems and solve them. And at the back end, people define changes to existing business process and run the processes in a new way.

Tools are a specialized infrastructure that helps people run lower-level processes within the innovation framework. At the front, people have ideas about new tools, or how to use them in a new way, define the ideas, evaluate them, and decide which tools to advance. In the middle, people define problems with the tools and solve them. And at the back end, they run the new tools in new ways.

With innovation processes and tools, people choose the best ideas, people solve problems and people implement solutions.

In order to choose the best ideas, people must communicate the ideas to the decision makers in a clear, rich, nuanced way. The better the idea is communicated, the better the decision. But it’s difficult to communicate an idea, even when the idea is not new. For example, try to describe your business model using just words. And it’s more difficult when the idea is new. Try to describe a new (untested) business model using just your words. For me, words are not a good way to communicate new ideas.

Improved communication improves innovation. To improve communication of ideas, use fewer words. Draw a picture, create a cartoon, make a storyboard, or make a video. Let the decision maker ask questions of your visuals and respond with another cartoon, a modified storyboard or a new sketch. Repeat the process until the decision maker stops asking questions. Because communication is improved, the quality of the decision is improved.

Improved problem solving improves innovation. To improve problem-solving, improve problem definition (the understanding of problem definition.) Create a block diagram of the problem – with elements of the system represented by blocks and labeled with nouns, and with actions and information flow represented by arrows labeled with verbs. Or create a sketch of the customer caught in the act of experiencing the problem. Define the problem in time (when it happens) so it can be solved before, during or after. And in all cases, limit yourself to one page. Continue to modify the visuals until there’s a common definition of the problem (the words stop.) When the problem is defined and communicated in this way, the problem solves itself. Problem-solving is seven-eighths problem definition.

Improved execution improves innovation. To improve execution, improve clarity of the definition of success. And again, minimize the words. Draw a picture that defines success using charts or graphs and data. Create the axes and label them (don’t forget the units of measure). Include data from the baseline product (or process) and define the minimum performance criterion in red. And add the sample size (number of tests.) Use one page for each definition of success and sequence them in order of importance. Start with the work that has never been done before. And to go deeper, define the test protocol used to create the data.

For a new business model, the one-page picture could be a process diagram with new blocks for new customers or partners or new arrows for new information flows. There could be time requirements (response time) or throughput requirements (units per month). Or it could be a series of sketches of new deliverables provided by the business model, each with clearly defined criteria to judge success. When communicated clearly to the teams, definitions of success are beacons of light that guide the boats as the tide pulls them through the project or when uncharted rocks suddenly appear to starboard.

Innovation demands communication and communication demands mechanisms. In the domain of uncertainty, words are not the best communicators. Create visual communication mechanisms that distill and converge on a common understanding.

A picture isn’t worth a thousand words, it gets rid of a thousand.

Image credit – Michael Coghlan

Understanding the trajectory of the competitive landscape

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

If you want to gain ground on your competition you’ve first got to know where things stand. Where are their advantages? Where are your advantages? Where is there parity? To quickly understand the situations there are three tricks: stay at a high level, represent the situation in a clear way and, where possible, use public information from their website.

A side-by-side comparison of the two companies’ products is the way to start. Create a common set of axes with price running south to north and performance (or output) running west to east. Make two copies and position them side-by-side on the page – yours on the left and theirs directly opposite on the right. Go to their website (and yours) and make a list of every product, its price and its output. (For prices of their products you may have to engage your sales team and your customers.) For each of your products place a symbol (the company logo) on your performance-price landscape and do the same for their products on their landscape. It’s now clear who has the most products, where their portfolio outflanks yours and where you outflank them. The clarity and simplicity will help everyone see things as they are – there may be angst but there will be no confusion and no disagreement. The picture is clear. But it’s static.

The areal differences define the gaps to close and the advantages to exploit. Now it’s time to define the momentum and trajectories of the portfolios to add a dynamic element. For your most recent product launch add a one next to its logo, for the second most recent add a two and for the third add three. These three regions of your portfolio are your most recent focus areas. This is your trajectory and this is where you have momentum. Extend and arrow in the direction of your trajectory. If you stay the course, this is where your portfolio will add mass. Do the same for your competitor and compare arrows. You know have a glimpse into the future. Are your arrows pointing in the same directions as theirs? Are they located in the same regions? How would feel if both companies continued on their trajectories? With this addition you have glimpse into the stay-the-course future. But will they stay the course? For that you need to look at the patent landscape.

Do a patent search on their patents and applications over the previous year and represent each with its most descriptive figure. Write a short thematic description for each, group like themes and draw a circle around them. Mark the circle with a one to denote last year’s patents. Repeat the process for two years ago and three years ago and mark each circle accordingly. Now you have objective evidence of the future. You know where they have been working and you know where they want to go. You have more than a glimpse into the future. You know their preferred trajectories. Reconcile their preferred trajectories with their price-performance landscapes and arrows 1, 2 and 3. If their preferred trajectories line up with their product momentum, it’s business as usual for them. If they contradict, they are playing a different game. And because it takes several years for patent applications to publish, they’ve been playing a new game for a while now.

Repeat the process for your patent landscape and flop it onto your performance-price landscape. I’m not sure what you’ll see, but you’ll know it when you see it. Then, compare yours with theirs and you’ll know what the competitive landscape will look like in three years. You may like what you see, or not. But, the picture will be clear. There may be discomfort, but there can be no arguments.

This process can also be used in the acquisition process to get a clear picture a company’s future state. In that way you can get a calibrated view three years into the future and use your crystal ball to adjust your offer price accordingly.

Image credit – Rob Ellis

If you don’t know the critical path, you don’t know very much.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Two words to live by: Critical Path.

By definition, the next task to work on is the next task on the critical path. How do you tell if the task is on the critical path? When you are late by one day on a critical path task, the project, as a whole, will finish a day late. If you are late by one day and the project won’t be delayed, the task is not on the critical path and you shouldn’t work on it.

Rule 1: If you can’t work the critical path, don’t work on anything.

Working on a non-critical path task is worse than working on nothing. Working on a non-critical path task is like waiting with perspiration. It’s worse than activity without progress. Resources are consumed on unnecessary tasks and the resulting work creates extra constraints on future work, all in the name of leveraging the work you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

How to spot the critical path? If a similar project has been done before, ask the project manager what the critical path was for that project. Then listen, because that’s the critical path. If your project is similar to a previous project except with some incremental newness, the newness is on the critical path.

Rule 2: Newness, by definition, is on the critical path.

But as the level of newness increases, it’s more difficult for project managers to tell the critical path from work that should wait. If you’re the right project manager, even for projects with significant newness, you are able to feel the critical path in your chest. When you’re the right project manager, you can walk through the cubicles and your body is drawn to the critical path like a divining rod. When you’re the right project manager and someone in another building is late on their critical path task, you somehow unknowingly end up getting a haircut at the same time and offering them the resources they need to get back on track. When you’re the right project manager, the universe notifies you when the critical path has gone critical.

Rule 3: The only way to be the right project manager is to run a lot of projects and read a lot. (I prefer historical fiction and biographies.)

Not all newness is created equal. If the project won’t launch unless the newness is wrestled to the ground, that’s level 5 newness. Stop everything, clear the decks, and get after it until it succumbs to your diligence. If the product won’t sell without the newness, that’s level 5 and you should behave accordingly. If the newness causes the product to cost a bit more than expected, but the project will still sell like nobody’s business, that’s level 2. Launch it and cost reduce it later. If no one will notice if the newness doesn’t make it into the product, that’s level 0 newness. (Actually, it’s not newness at all, it’s unneeded complexity.) Don’t put in the product and don’t bother telling anyone.

Rule 4: The newness you’re afraid of isn’t the newness you should be afraid of.

A good project plan starts with a good understanding of the newness. Then, the right project work is defined to make sure the newness gets the attention it deserves. The problem isn’t the newness you know, the problem is the unknown consequence of newness as it ripples through the commercialization engine. New product functionality gets engineering attention until it’s run to ground. But what if the newness ripples into new materials that can’t be made or new assembly methods that don’t exist? What if the new materials are banned substances? What if your multi-million dollar test stations don’t have the capability to accommodate the new functionality? What if the value proposition is new and your sales team doesn’t know how to sell it? What if the newness requires a new distribution channel you don’t have? What if your service organization doesn’t have the ability to diagnose a failure of the new newness?

Rule 5: The only way to develop the capability to handle newness is to pair a soon-to-be great project manager with an already great project manager.

It may sound like an inefficient way to solve the problem, but pairing the two project managers is a lot more efficient than letting a soon-to-be great project manager crash and burn. After an inexperienced project manager runs a project into the ground, what’s the first thing you do? You bring in a great project manager to get the project back on track and keep them in the saddle until the product launches. Why not assume the wheels will fall off unless you put a pro alongside the high potential talent?

Rule 6: When your best project managers tell you they need resources, give them what they ask for.

If you want to deliver new value to new customs there’s no better way than to develop good project managers. A good project manager instinctively knows the critical path; they know how the work is done; they know to unwind situations that needs to be unwound; they have the personal relationships to get things done when no one else can; because they are trusted, they can get people to bend (and sometimes break) the rules and feel good doing it; and they know what they need to successfully launch the product.

If you don’t know your critical path, you don’t know very much. And if your project managers don’t know the critical path, you should stop what you’re doing, pull hard on the emergency break with both hands and don’t release it until you know they know.

Image credit – Patrick Emerson

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski