Posts Tagged ‘Lessons Learned’

Words To Live By

What people think about you is none of your business.

What people think about you is none of your business.

If you’re afraid to be wrong, you shouldn’t be setting direction.

Think the better of people, as they’ll be better for it.

When you find yourself striving, pull the emergency brake and figure out how to start thriving.

If you want the credit, you don’t want to make a difference.

If you’re afraid to use your best judgment, find a mentor.

Family first, no exceptions.

When you hold a mirror to the organization, you demonstrate that you care.

If you want to grow people and you invest less than 30% of your time, you don’t want to grow them.

When someone gives you an arbitrary completion date, they don’t know what they’re doing.

When the Vice President wants to argue with the physics, let them.

When all else fails, use your best judgment.

If it’s not okay to tell the truth, work for someone else.

The best way to make money is not the best way to live.

When someone yells at you, that says everything about them and nothing about you.

Trust is a result. Think about that.

When you ask for the impossible, all the answers will be irrational.

No one can diminish you without your consent.

If you don’t have what you want, why not try to want what you have?

When you want to control things, you limit the growth of everyone else.

People can tell when you’re telling the truth, so tell them.

If you find yourself watching the clock, find yourself another place to work.

When someone does a great job, tell them.

If you have to choose between employment and enjoyment, choose the latter.

If you’re focused on cost reduction, you’re in a race to the bottom.

The best way to help people grow is to let them do it wrong (safely).

When you hold up a mirror to the organization, no one will believe what they see.

If you’re not growing your replacement, what are you doing?

If you’re not listening, you’re not learning.

When someone asks for help, help them.

If you think you know the right answer, you’re the problem.

When someone wants to try something new, help them.

Whatever the situation, tell the truth, and love everyone.

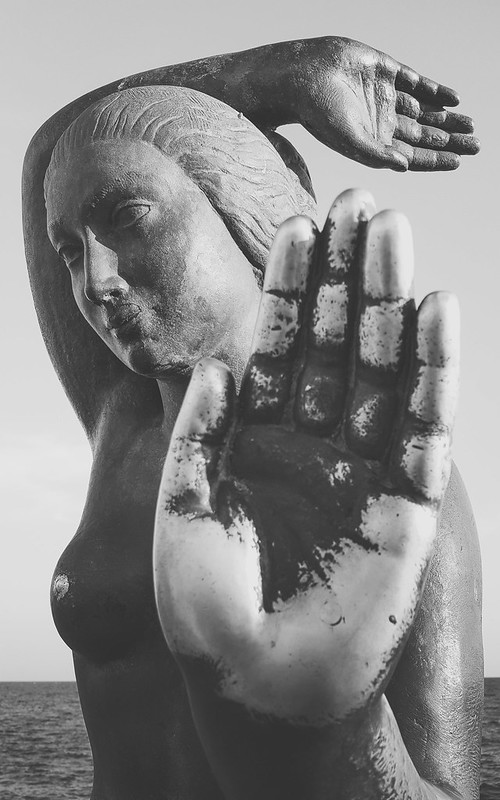

Image credit — John Fife

Want to succeed? Learn how to deliver customer value.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whenever the discussion turns to customer value, expect confusion, disagreement, and, likely, anger. To help things move forward, here’s an operational definition I’ve found helpful:

When they buy it for more than your cost to make it, you have customer value.

And when there’s no way to pull out of the death spiral of disagreement, use this operational definition to avoid (or stop) bad projects:

When no one will buy it, you don’t have customer value and it’s a bad project.

As two words, customer and value don’t seem all that special. But, when you put them together, they become words to live by. But, also, when you do put them together, things get complicated. Here’s why.

To provide customer value, you’ve got to know (and name) the customer. When you asked “Who is the customer?” the wheels fall off. Here are some wrong answers to that tricky question. The Board of Directors is the customer. The shareholders are the customers. The distributor is the customer. The OEM that integrates your product is the customer. And the people that use the product are the customer. Here’s an operational definition that will set you free:

When someone buys it, they are the customer.

When the discussions get sticky, hold onto that definition. Others will try to bait you into thinking differently, but don’t bite. It will be difficult to stand your ground. And if you feel the group is headed in the wrong direction, try to set things right with this operational definition:

When you’ve found the person who opens their wallet, you’ve found the customer.

Now, let’s talk about value. Isn’t value subjective? Yes, it is. And the only opinion that matters is the customer’s. And here’s an operational definition to help you create customer value:

When you solve an important customer problem, they find it valuable.

And there you have it. Putting it all together, here’s the recipe for customer value:

- Understand who will buy it.

- Understand their work and identify their biggest problem.

- Solve their problem and embed it in your offering.

- Sell it for more than it costs you to make it.

Image credit — Caroline

Learn to Recognize Waiting

If you want to do a task, but you don’t have what you need, that’s waiting for a support resource. If you need a tool, but you don’t have it, you wait for a tool. If you need someone to do the task, but you don’t have anyone, you wait for people. If you need some information to make a decision, but you don’t have it, you wait for information.

If a tool is expensive, usually you have to wait for it. The thinking goes like this – the tool is expensive, so let’s share the cost over too many projects and too many teams. Sure, less work will get done, but when we run the numbers, the tool will look less expensive because it’s used by many people. If you see a long line of people (waiting) or a signup list (people waiting at their desks), what they are waiting for is usually an expensive tool or resource. In that way, to find the cause of waiting, stand at the front of the line and look around. What you see is the cause of the waiting.

If the tool isn’t expensive, buy another one and reduce the waiting. If the tool is expensive, calculate the cost of delay. Cost of delay is commonly used with product development projects. If the project is delayed by a month, the incremental revenue from the product launch is also delayed by a month. That incremental revenue is the cost of delaying the project by a month. When the cost of delay is larger than the cost of an expensive tool, it makes sense to buy another expensive tool. But, to purchase that expensive tool requires multiple levels of approvals. So, the waiting caused by the tool results in waiting for approval for the new tool. I guess there’s a cost of delay for the approval process, but let’s not go there.

Most companies have more projects than people, and that’s why projects wait. And when projects wait, projects are late. Adding people is like getting another expensive tool. They are spread over too many projects, and too little gets done. And like with expensive tools, getting more people doesn’t come easy. New hires can be justified (more waiting in the approval queue), but that takes time to find them, hire them, and train them. Hiring temporary people is a good option, though that can seem too expensive (higher hourly rate), it requires approval, and it takes time to train them. Moving people from one project to another is often the best way because it’s quick and the training requirement is less. But, when one project gains a person, another project loses one. And that’s often the rub.

When it’s time to make an important decision and the team has to wait for missing information, the project waits. And when projects wait, projects are late. It’s difficult to see the waiting caused by missing or uncommunicated information, but it can be done. The easiest to see when the information itself is a project deliverable. If a milestone review requires a formal presentation of the information, the review cannot be held without it. The delay of the milestone review (waiting) is objective evidence of missing information.

Information-based waiting is relatively easy to see when the missing information violates a precedent for decision making. For example, if the decision is always made with a defined set of data or information, and that information is missing, the precedent is violated and everyone knows the decision cannot be made. In this case, everyone’s clear why the decision cannot be made, everyone’s clear on what information is missing, and everyone’s clear on who dropped the ball.

It’s most difficult to recognize information-based waiting when the decision is new or different and requires judgment because there’s no requirement for the data and there’s no precedent to fall back on. If the information was formally requested and linked to the decision, it’s clear the information is missing and the decision will be delayed. But if it’s a new situation and there’s no agreement on what information is required for the decision, it’s almost impossible to discern if the information is missing. In this situation, it comes down to trust in the decision-maker. If you trust the decision-maker and they say there’s information missing, then there’s information missing. If you trust the decision-maker and they say there’s no information missing, they should make the decision. But if you don’t trust the decision-maker, then all bets are off.

In general, waiting is bad. And it’s helpful if you can recognize when projects are waiting. Waiting is especially bad went the delayed task is on the critical path because when the project is waiting on a task that’s on the critical path, there’s a day-for-day slip in the completion date. Hint: it’s important to know which tasks and decisions are on the critical path.

Image credit — Tomasz Baranowski

The Toughest Word to Say

As the world becomes more connected, it becomes smaller. And as it becomes smaller, competition becomes more severe. And as competition increases, work becomes more stressful. We live in a world where workloads increase, timelines get pulled in, metrics multiply and “accountability” is always the word of the day. And in these trying times, the most important word to say is also the toughest.

As the world becomes more connected, it becomes smaller. And as it becomes smaller, competition becomes more severe. And as competition increases, work becomes more stressful. We live in a world where workloads increase, timelines get pulled in, metrics multiply and “accountability” is always the word of the day. And in these trying times, the most important word to say is also the toughest.

When your plate is full and someone tries to pile on more work, what’s the toughest word to say?

When the project is late and you’re told to pull in the schedule and you don’t get any more resources, what’s the toughest word to say?

When the technology you’re trying to develop is new-to-world and you’re told you must have it ready in three months, what’s the toughest word to say?

When another team can’t fill an open position and they ask you to fill in temporarily while you do your regular job, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re asked to do something that will increase sales numbers this quarter at the expense of someone else’s sales next quarter, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re told to use a best practice that isn’t best for the situation at hand, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re told to do something and how to do it, what’s the toughest word to say?

When your boss asks you something that you know is clearly their responsibility, what’s the toughest word to say?

Sometimes the toughest word is the right word.

Image credit –Noirathse’s Eye

Two Questions to Grow Your Business

Two important questions to help you grow your business:

Two important questions to help you grow your business:

- Is the problem worth solving?

- When do you want to learn it’s not worth solving?

No one in your company can tell you if the problem is worth solving, not even the CEO. Only the customer can tell you if the problem is worth solving. If potential customers don’t think they have the problem you want to solve, they won’t pay you if you solve it. And if potential customers do have the problem but it’s not that important, they won’t pay you enough to make your solution profitable.

A problem is worth solving only when customers are willing to pay more than the cost of your solution.

Solving a problem requires a good team and the time and money to run the project. Project teams can be large and projects can run for months or years. And projects require budgets to buy the necessary supplies, tools, and infrastructure. In short, solving problems is expensive business.

It’s pretty clear that it’s far more profitable to learn a problem is not worth solving BEFORE incurring the expense to solve it. But, that’s not what we do. In a ready-fire-aim way, we solve the problem of our choosing and try to sell the solution.

If there’s one thing to learn, it’s how to verify the customer is willing to pay for your solution before incurring the cost to create it.

Image credit — Milos Milosevic

When Problems Are Bigger Than They Seem

If words and actions are different, believe the actions.

If the words change over time, don’t put stock in the person delivering them.

If a good friend doesn’t trust someone, neither should you.

If the people above you don’t hold themselves accountable, yet they try to hold you accountable, shame on them.

If people are afraid to report injustices, it’s just a matter of time before the best people leave.

If actions are consistently different than the published values, it’s likely the values should be up-revved.

If you don’t trust your leader, respect your instincts.

If people are bored and their boredom is ignored, expect the company to death spiral into the ground.

If behaviors are different than the culture, the culture isn’t the culture.

If all the people in a group apply for positions outside the group, the group has a problem.

When actions seen by your eyes are different than the rhetoric force-fed into your ears, believe your eyes.

If you think your emotional wellbeing is in jeopardy, it is.

If to preserve your mental health you must hunker down with a trusted friend, find a new place to work.

If people are afraid to report injustices, company leadership has failed.

If the real problems aren’t discussed because they’re too icky, there’s a bigger problem.

If everyone in the group applies for positions outside the group and HR doesn’t intervene, the group isn’t the problem.

And to counter all this nonsense:

If someone needs help, help them.

If someone helps you, thank them.

If someone does a good job, tell them.

Rinse, and repeat.

Dare To Feel Stuck

When you’re stuck, it’s not because you don’t have good ideas. And it’s not because you’re not smart. You’re stuck because you’re trying to do something difficult. You’re stuck because you’re trying to triangulate on something that’s not quite fully formed. Simply put, you’re stuck because it’s not yet time to be unstuck.

Anyone can avoid being stuck by doing what was done last time. But that’s not unsticking yourself, that’s copping out. That’s giving in to something lesser. That’s dumbing yourself down. That’s letting yourself off the hook. That’s not believing in yourself. That’s not doing what you were born to do. That’s not unsticking, that’s avoiding the discomfort of being stuck.

Being stuck – not knowing what to do or what to write – is not a bad thing. Sure, it feels bad, but it’s a sign you’re trekking in uncharted territory. It may be a new design space or it may be new behavioral space, but make no mistake – you’re swimming in a new soup. If you’ve already mastered tomato soup, you won’t feel stuck until you jump into a pool filled with chicken noodle. And when you do, don’t beat yourself up because your lungs are half-filled with noodles. Instead, simply recognize that chicken soup is different than tomato. Pat yourself on the back for jumping in without a life preserver. And even as you tread water, congratulate yourself for not drowning.

Unsticking takes time and you can’t rush it. But that’s where most fail – they climb out of the soup too soon. The soup doesn’t feel good because it’s too hot, too salty, or too noodly, so they get out. They can’t stand the discomfort so they get out before the bodies can acclimate and figure out how to swim in a new way. The best way to avoid getting stuck is to stay out of the soup and the next best way is to get out too early. But it’s not best to avoid being stuck.

Life’s too short to avoid being stuck. Sure, you may prevent some discomfort, but you also prevent growth and learning. Do you want to get to your deathbed and realize you limited your personal growth because you were afraid to feel the discomfort of being stuck? Imagine getting to the end of your life and all you can think of is the see of things you didn’t experience because you were unwilling to feel stuck.

Stuck is not bad, it just feels bad. Instead of seeing the discomfort as discomfort, can you learn to see it as the precursor to growth? Can you learn to see the discomfort as an indicator of immanent learning? Can you learn to see it as the tell-tale sign of your quest for knowledge and understanding?

If you’re not yet ready to feel stuck, I get that. But to get yourself ready, keep your eye out for people around you who have dared to get stuck. Learn to recognize what it looks like. And when you do find someone who is stuck, tell them they are doing a brave thing. Tell them that it’s supposed to feel uncomfortable. Tell them that no one has ever died from the discomfort of being stuck. And tell them that staying with the discomfort is the best way to get unstuck. And thank them for demonstrating the right behavior.

Image credit — NeilsPhotography

As a leader, be truthful and forthcoming.

Have you ever felt like you weren’t getting the truth from your leader? You know – when they say something and you know that’s not what they really think. Or, when they share their truth but you can sense that they’re sharing only part of the truth and withholding the real nugget of the truth? We really have no control over the level of forthcoming of our leaders, but we do have control over how we respond to their incomplete disclosure.

There are times when leaders cannot, by law, disclose things. But, even then, they can make things clear without disclosing what legally cannot be disclosed. For example, they can say: “That’s a good question and it gets to the heart of the situation. But, by law, I cannot answer that question.” They did not answer the question, but they did. They let you know that you understand the situation; they let you know that there is an answer; and the let you know why they cannot share it with you. As the recipient of that non-answer answer, I respect that leader.

There are also times when a leader withholds information or gives a strategically partial response for inappropriate reasons. When a leader withholds information to manipulate or control, that’s inappropriate. It’s also bad leadership. When a leader withholds information from their smartest team members, they lose trust. And when leaders lose trust, the best people are crestfallen and withhold their best work. The thinking goes like this. If my leader doesn’t trust me enough to share the complete set of information with me it’s because they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust and they don’t think highly of me. And if they don’t think I’m worthy of their trust, they don’t understand who I am and what I stand for. And if they don’t understand me and know what I stand for, they’re not worthy of my best work.

As a leader, you must share all you can. And when you can’t, you must tell your team there are things you can’t share and tell them the reasons why. Your team can handle the fact that there are some things you cannot share. But what your team cannot hand is when you withhold information so you can gain the upper hand on them. And your team can tell when you’re withholding with your best interest in mind. Remember, you hired them because they were smart, and their smartness doesn’t go away just because you want to control them.

If your direct reports always tell you they can get it done even when they don’t have the capacity and capability, that’s not the behavior you want. If your direct reports tell you they can’t get it done when they can’t get it done, that’s the behavior you want. But, as a leader, which behavior do you reward? Do you thank the truthful leader for being truthful about the reality of insufficient resources and do you chastise the other leader for telling you what you want to hear? Or, do you tell the truthful leader they’re not a team player because team players get it done and praise the unjustified can-do attitude of the “yes man” leader? As a leader, I suggest you think deeply about this. As a direct report of a leader, I can tell you I’ve been punished for responding in way that was in line with the reality of the resources available to do the work. And I can also tell you that I lost all respect for that leader.

As a leader, you have three types of direct reports. Type I are folks are happy where they are and will do as little as possible to keep it that way. Type II are people that are striving for the next promotion and will tell you whatever you want to hear in order to get the next job. Type III are the non-striving people who will tell you what you need to hear despite the implications to their career. Type I people are good to have on your team. They know what they can do and will tell you when the work is beyond their capability. Type II people are dangerous because they think only of themselves. They will hang you out to dry if they think it will advance their career. And Type III people are priceless.

Type III people care enough to protect you. When you ask them for something that can’t be done, they care enough about you to tell you the truth. It’s not that they don’t want to get it done, they know they cannot. And they’re willing to tell you to your face. Type II people don’t care about you as a leader; they only care about themselves. They say yes when they know the answer is no. And they do it in a way that absolves them of responsibility when the wheels fall off. As a leader, which type do you want on your team? And as a leader, which type do you promote and which do you chastise. And, how do you feel about that?

As a leader, you must be truthful. And when you can’t disclose the full truth, tell people. And when your Type II direct reports give you the answer they know you want to hear, call them on their bullshit. And when your Type III folks give you the answer they know you don’t want to hear, thank them.

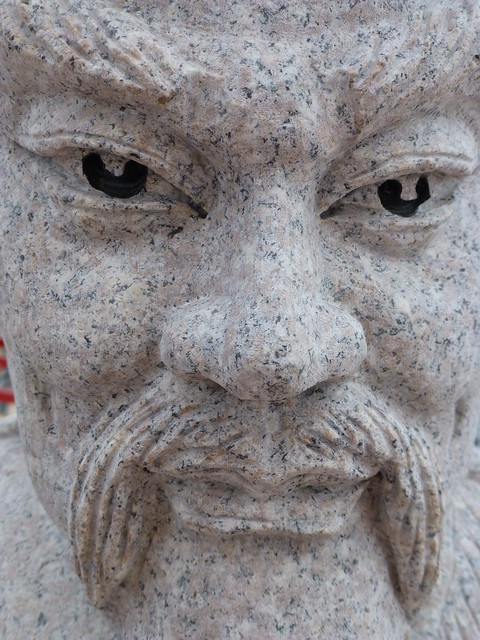

Image credit — Anandajoti Bhikkhu

Whether it goes well or poorly, what matters is how you respond.

When was the last time you taught someone a new method or technique? What was their reaction? How did it make you feel? Will you do it again?

When was the last time you taught someone a new method or technique? What was their reaction? How did it make you feel? Will you do it again?

When was the last time you learned something new from a colleague? What was your reaction? What did you do so it would happen again?

When was the last time you woke up early because you were excited to go to work? How did you feel about that? What can change so it happens once a week?

When was the last time you had a crazy idea and your colleagues helped you make it real? How did you feel about that? How can you do it for them? What can you do to make it happen more frequently?

When was the last time you had a crazy idea and it was squelched because it violated a successful recipe? How did you feel about that? What can you do so it happens differently next time?

When was the last time you used your good judgement without asking for permission? How did you feel about that? What can you do to give others the confidence to use their best judgement?

When was the last time someone gave you credit for doing good work? And when was the last time you did the same for someone else? What can you do so the behavior blossoms into common practice?

When was the last time you openly contradicted a majority opinion with a dissenting minority opinion? Though it was received poorly, you must do it again. The majority needs to hear your dissenting opinion so they can sharpen their thinking.

When was the last time you gave good advice to a younger colleague? How can you systematize that type of behavior?

When was the last time you did work so undeniably good that others twisted it a bit and adopted it as their own? Don’t feel badly. When doing innovative work this is what success looks like. All that really matters is your customers realize the value from the work and not who gets credit. What can you do so this type of thing happens as a matter of course?

Good things happen and bad things happen. That’s how life goes. But the important part is you pay attention to what worked and what didn’t. And the second important part is actively making the good stuff happen more frequently and the bad stuff happen less frequently.

Image credit — jacquemart

As a leader, your response is your responsibility.

When you’re asked to do more work that you and your team can handle, don’t pass it onto your team. Instead, take the heat from above but limit the team’s work to a reasonable level.

When you’re asked to do more work that you and your team can handle, don’t pass it onto your team. Instead, take the heat from above but limit the team’s work to a reasonable level.

When the number of projects is larger than the budget needed to get them done, limit the projects based on the budget.

When the team knows you’re wrong, tell them they’re right. And apologize.

When everyone knows there’s a big problem and you’re the only one that can fix it, fix the big problem.

When the team’s opinion is different than yours, respect the team’s opinion.

When you make a mistake, own it.

When you’re told to do turn-the-crank work and only turn-the-crank work, sneak in a little sizzle to keep your team excited and engaged.

When it’s suggested that your team must do another project while they are fully engaged in an active project, create a big problem with the active project to delay the other project.

When the project is going poorly, be forthcoming with the team.

When you fail to do what you say, apologize. Then, do what you said you’d do.

When you make a mistake in judgement which creates a big problem, explain your mistake to the team and ask them for help.

If you’ve got to clean up a mess, tell your team you need their help to clean up the mess.

When there’s a difficult message to deliver, deliver it face-to-face and in private.

When your team challenges your thinking, thank them.

When your team tells you the project will take longer than you want, believe them.

When the team asks for guidance, give them what you can and when you don’t know, tell them.

As leaders, we don’t always get things right. And that’s okay because mistakes are a normal part of our work. And projects don’t always go as planned, but that’s okay because that’s what projects do. And we don’t always have the answers, but that’s okay because we’re not supposed to. But we are responsible for our response to these situations.

When mistakes happen, good leaders own them. When there’s too much work and too little time, good leaders tell it like it is and put together a realistic plan. And when the answers aren’t known, a good leader admits they don’t know and leads the effort to figure it out.

None of us get it right 100% of the time. But what we must get right is our response to difficult situations. As leaders, our responses should be based on honesty, integrity, respect for the reality of the situation and respect for people doing the work.

Image credit – Ludovic Tristan

How to Prevent Depletion

On every operating plan there are more projects than there are people to do them and at every meeting there more new deliverables than people to take them on. At every turn, our demand for increased profits pushes our people for more. And, to me, I think this is the reason every day feel fuller than the last.

On every operating plan there are more projects than there are people to do them and at every meeting there more new deliverables than people to take them on. At every turn, our demand for increased profits pushes our people for more. And, to me, I think this is the reason every day feel fuller than the last.

This year do you have more things to accomplish or fewer? Do you have more meetings or fewer? Do you get more emails or fewer?

We add work to people’s day as if their capacity to do work is infinite. And we add metrics to measure them to make sure they get the work done. And that’s a recipe for depletion. At some point, even the best, most productive people reach their physical and emotional limits. And at some point, as the volume of work increases, we all become depleted. It’s not that we’re moving slowly, being wasteful or giving it less than our all. When the work exceeds our capacity to do it, we run out of gas.

Here are some thoughts that may help you over the next year.

The amount of work you will get done this year is the same as you got done last year. But don’t get sidetracked here. This has nothing to do with the amount of work you were asked to do last year. Because you didn’t complete everything you were asked to do last year, the same thing will happen this year unless the amount of work on this year’s plan is equal to the amount of work you actually accomplished last year. Every year, scrub a little work off your yearly commitments until the work content finally equals your capacity to get it done.

Once the work content of your yearly plan is in line, the mantra becomes – finish one before you start one. If you had three projects last year and you finished one, you can add one project this year. If you didn’t finish any projects last year you can’t start one this year, at least until you finish one this year. It’s a simple mantra, but a powerful one. It will help you stop starting and start finishing.

There’s a variant to the finish-before-you-start approach that doesn’t have to wait for the completion of a long project. Instead of finishing a project, unimportant projects are stopped before they’re finished. This is loosely known as – stop doing before start doing. Stopping is even more powerful than finishing because low value work is stopped and the freed-up resources are immediately applied to higher value work. This takes judgement and courage to stop a dull project, but it’s well worth the discomfort.

If you want to get ahead of the game, create a stop-doing list. For each item on the list estimate how much time you will free up and sum the freed-up time for the lot. Be ruthless. Stop all but the most important work. And when your boss says you can’t stop something because it’s too important, propose that you stop for a week and see what happens. And when no one notices you stopped, propose to stop for a month and see what happens. Rinse and repeat.

When the amount of work you have to get done fits with your capacity to do it, your physical and mental health will improve. You’ll regain that spring in your step and you’ll be happier. And the quality of your work will improve. But more importantly, your family life and personal relationships will improve. You’ll be able to let go of work and be fully present with your friends and family.

Regardless of the company’s growth objectives, one person can only do the work of one person. And it’s better for everyone (and the company) if we respect this natural constraint.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski