Posts Tagged ‘Lessons Learned’

Two Sides of the Same Coin

Praise is powerful, but not when you don’t give it.

Praise is powerful, but not when you don’t give it.

People learn from mistakes, but not when they don’t make them.

Wonderful solutions are wonderful, but not if there are no problems.

Novelty is good, but not if you do what you did last time.

Disagreement creates deeper understanding, but not if there’s 100% agreement.

Consensus is safe, but not when it’s time for original thought.

Progress is made through decisions, but not if you don’t make them.

It’s skillful to constrain the design space, but not if it doesn’t contain the solution.

Trust is powerful, but not before you build it.

A mantra: Praise people in public.

If you want people to learn, let them make mistakes.

Wonderful problems breed wonderful solutions.

If you want novelty, do new things.

There can be too little disagreement.

Consensus can be dangerous.

When it’s decision time, make one.

Make the design space as small as it can be, but no smaller.

Build trust before you need it.

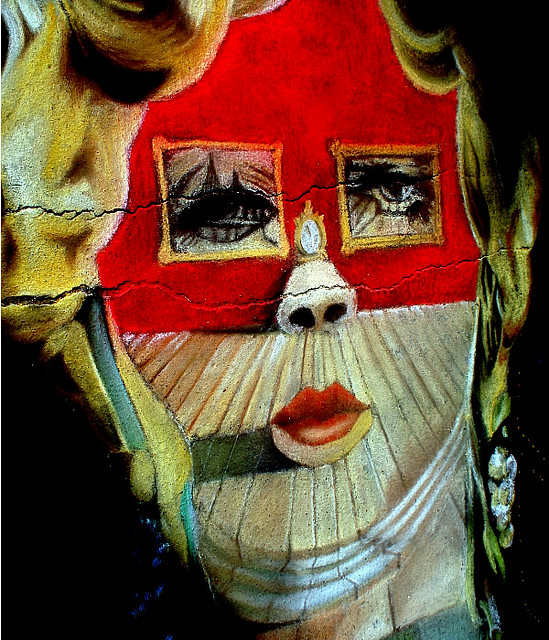

Image credit – Ralf St.

Projects, Products, People, and Problems

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

Solve the toughest problems first. When do you want to learn the problem is not solvable?

Sometimes slower is faster.

Problems aren’t problems until you realize you have them. Before that, they’re problematic.

If you can’t put it on one page, you don’t understand it. Or, it’s complex.

Take small bites. And if that doesn’t work, take smaller bites.

To get more projects done, do fewer of them.

Say no.

Stop starting and start finishing.

Effectiveness over efficiency. It’s no good to do the wrong thing efficiently.

Function first, no exceptions. It doesn’t matter if it’s cheaper to build if it doesn’t work.

No sizzle, no sale.

And customers are the ones who decide if the sizzle is sufficient.

Solve a customer’s problem before solving your own.

Design it, break it, and fix it until you run out of time. Then launch it.

Make the old one better than the new one.

Test the old one to set the goal. Test the new one the same way to make sure it’s better.

Obsolete your best work before someone else does.

People grow when you create the conditions for their growth.

If you tell people what to do and how to do it, you’ll get to eat your lunch by yourself every day.

Give people the tools, time, training, and a teacher. And get out of the way.

If you’ve done it before, teach someone else to do it.

Done right, mentoring is good for the mentor, the mentee, and the bottom line.

When in doubt, help people.

Trust is all-powerful.

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit — Hartwig HKD

Working In Domains of High Uncertainty

X: When will you be done with the project?

X: When will you be done with the project?

Me: This work has never been done before, so I don’t know.

X: But the Leadership Team just asked me when the project will be done. So, what should I say?

Me: Since nothing has changed since the last time you asked me, I still don’t know. Tell them I don’t know.

X: They won’t like that answer.

Me: They may not like the answer, but it’s the truth. And I like telling the truth.

X: Well, what are the steps you’ll take to complete the project?

Me: All I can tell you is what we’re trying to learn right now.

X: So all you can tell me is the work you’re doing right now?

Me: Yes.

X: It seems like you don’t know what you’re doing.

Me: I know what we’re doing right now.

X: But you don’t know what’s next?

Me: How could I? If this current experiment goes up in smoke, the next thing we’ll do is start a different project. And if the experiment works, we’ll do the next right thing.

X: So the project could end tomorrow?

Me: That’s right.

X: Or it could go on for a long time?

Me: That’s right too.

X: Are you always like this?

Me: Yes, I am always truthful.

X: I don’t like your answers. Maybe we should find someone else to run the project.

Me: That’s up to you. But if the new person tells you they know when the project will be done, they’re the wrong person to run the project. Any date they give you will be a guess. And I would not want to be the one to deliver a date like that to the Leadership Team.

X: We planned for the project to be done by the end of the year with incremental revenue starting in the first quarter of next year.

Me: Well, the project work is not bound by the revenue plan. It’s the other way around.

X: So, you don’t care about the profitability of the company?

Me: Of course I care. That’s why we chose this project – to provide novel customer value and sell more products.

X: So the project is intended to deliver new value to our customers?

Me: Yes, that’s how the project was justified. We started with an important problem that, if solved, would make them more profitable.

X: So you’re not just playing around in the lab.

Me: No, we’re trying to solve a customer problem as fast as we can. It only looks like we’re playing around.

X: If it works, would our company be more profitable?

Me: Absolutely.

X: Well, how can I help?

Me: Please meet with the Leadership Team and thank them for trusting us with this important project. And tell them we’re working as fast as we can.

Image credit – Florida Fish and Wildlife

X: Me: format stolen from Simon Wardley (@swardley). Thank you, Simon.

What does it mean to have enough?

What does it mean to have enough?

What does it mean to have enough?

If you don’t want more, doesn’t that mean you have enough?

And if you want what you have, doesn’t that mean you don’t want more?

If you had more, would that make things better?

If you had more, what would stop you from wanting more?

What would it take to be okay with what you have?

If you can’t see what you have and then someone helps you see it, isn’t that like having more?

What do you have that you don’t realize you have?

Do you have a pet?

Do you have the ability to walk?

Do you have friends and family?

Do you have people that rely on you?

Do you have a place where people know you?

Do you have people that care about you?

Do you have a warm jacket and hat?

When you have enough you have the freedom to be yourself.

And when you have enough it’s because you decided you have enough.

Image credit — Irudayam

There is always something to build on.

To have something is better than to have nothing, and to focus on everything dilutes progress and leads to nothing. In that way, something can be better than everything.

To have something is better than to have nothing, and to focus on everything dilutes progress and leads to nothing. In that way, something can be better than everything.

What do you have and how might you put it to good use right now?

Everything has a history. What worked last time? What did not? What has changed?

What information do you have that you can use right now? And what’s the first bit of new information you need and what can you to do get it right now?

It is always a brown-field site and never a green-field. You never start from scratch.

What do you have that you can build on right now? How might you use it to springboard into the future?

When it’s time to make a decision, there is always some knowledge about the current situation but the knowledge is always incomplete.

What knowledge do you have right now and how might you use it to advance the cause? What’s the next bit of knowledge you need and why aren’t you trying to acquire that knowledge right now?

You always have your intuition and your best judgment. Those are both real things. They’re not nothing.

How can you use your intuition to make progress right now? How can you use your judgment to advance things right here and right now?

There’s a singular recipe in all this.

Look for what you have (and you always have something) and build on it right now. Then look again and repeat.

Image credit – Jeffrey

Too Much of a Good Thing

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Too much focus on product cost reduction prevents product enhancements, blocks new customer value propositions, and stifles top-line growth.

Voice of the Customer (VOC) activities are good.

Because customers don’t know what’s possible, too much focus on VOC silences the Voice of the Technology (VOT), blocks new technologies, and prevents novel value propositions. Just because customers aren’t asking for it doesn’t mean they won’t love it when you offer it to them.

Standard work is highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company is focused on standard work, novelty is squelched, new ideas are scuttled, and new customer value never sees the light of day.

Best practices are highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company defaults to best practices, novel projects are deselected, risk is radically reduced (which is super risky), people are afraid to try new things and use their judgment, new products are just like the old ones (no sizzle), and top-line growth is gifted to your competitors.

Consensus-based decision-making reduces bad decisions.

In domains of high uncertainty, consensus-based decision-making reduces projects to the lowest common denominator, outlaws the use of judgment and intuition, slows things to a crawl, and makes your most creative people leave the company.

Contrary to Mae West’s maxim, too much of a good thing isn’t always wonderful.

Image credit — Krassy Can Do It

The People Part of the Business

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Scan your organization for single-point failure modes, where if one person leaves the wheels would fall off. For the single-point failure mode, move a new person into the role and have the replaced person teach their replacement how to do the job. Transfer the knowledge before the knowledge walks out the door.

Scan your organization for people who you think can grow into a role at least two levels above their existing level. Move them up one level now, sooner than they and the organization think they’re ready. And support them with a trio of senior leaders. Error on the side of moving up too few people and providing too many supporting resources.

Scan your organization for people who exert tight control on their team and horde all the sizzle for themselves. Help these people work for a different company. Don’t wait. Do it now or your best young talent will suffocate and leave the company.

Scan your organization for people who are in positions that don’t fit them and move them to a position that does. They will blossom and others will see it, which will make it safer and easier for others to move to positions that fit them. Soon enough, almost everyone will have something that fits them. And remember, sometimes the position that fits them is with another company.

Scan your organization for the people who work in the background to make things happen. You know who I’m talking about. They’re the people who create the conditions for the right decisions to emerge, who find the young talent and develop them through the normal course of work, who know how to move the right resources to the important projects without the formal authority to do so, who bring the bad news to the powerful so the worthy but struggling projects get additional attention and the unworthy projects get stopped in their tracks, who bring new practices to new situations but do it through others, who provide air cover so the most talented people can do the work everyone else is afraid to try, who overtly use their judgment so others can learn how to use theirs, and who do the right work the right way even when it comes at their own expense. Leave these people alone.

When you take care of the people part of the business, all the other parts will take care of themselves.

Image credit – are you my rik?

What To Do When It Matters

If you see something that matters, say something.

If you see something that matters, say something.

If you say something and nothing happens, you have a choice – bring it up again, do something, or let it go.

Bring it up again when you think your idea was not understood. And if it’s still not understood after the second try, bring it up a third time. After three unsuccessful tries, stop bringing it up.

Now your choice is to do something or let it go.

Do something to help people see your idea differently. If it’s a product or technology, build a prototype and show people. This makes the concept more real and facilitates discussion that leads to new understanding and perspectives. If it’s a new value proposition, create a one-page sales tool that defines the new value from the customers’ perspective and show it to several customers. Make videos of the customers’ reactions and show them to people that matter. The videos let others experience the customers’ reactions first-hand and first-hand customer feedback makes a difference. If is a new solution to a problem, make a prototype of the solution and show it to people that have the problem. People with problems react well to solutions that solve them.

When people see you invest time to make a prototype or show a concept to customers, they take you and your concept more seriously.

If there’s no real traction after several rounds of doing something, let it go. Letting it go releases you from the idea and enables you to move on to something better. Letting it go allows you to move on. Don’t confuse letting it go with doing nothing. Letting it go is an action that is done overtly.

The number of times to bring things up is up to you. The number of prototypes to build is up to you. And the sequence is up to you. Sometimes it’s right to forgo prototypes and customer visits altogether and simply let it go.

But don’t worry. Because it matters to you, you’ll figure out the best way to move it forward. Follow your instincts and don’t look back.

Image credit – Peter Addor

If you want to make progress, make a map.

Fascination with the idealized future state isn’t ideal. Before moving forward, define the current state of things.

Fascination with the idealized future state isn’t ideal. Before moving forward, define the current state of things.

Improvement opportunities mean nothing unless they come from a deep understanding of the state of things as they are. Define things as they are before settling on improvement opportunities.

If you want to converge on a common understanding of how things are, make a map.

In times of uncertainty, there’s no way to know the destination. Assess your location, look for low-energy paths, and investigate several in parallel.

If you want to understand the situation as it stands, try to make a map. The gaps in the map define your learning objectives. And once the map hangs together, show it to someone you trust and refine it.

Before there can be agreement on potential solutions, there must be agreement on the situation as it is. Take time to make a map of the situation and show it to those who will decide on potential solutions. Create potential solutions only after everyone agrees on the situation as it stands.

If there’s disagreement on the map of the current state, break the regions of disagreement into finer detail until there is agreement.

It may seem slow and wasteful to make maps and create a common understanding of how things are. But if you want to know slow and wasteful, look at how long things take when that work isn’t done.

If you want to make progress, make a map.

Image credit — maximilianschiffer

Function first, no exceptions.

Before a design can be accused of having too much material and labor costs, it must be able to meet its functional specifications. Before that is accomplished, it’s likely there’s not enough material and labor in the design and more must be added to meet the functional specifications. In that way, it likely doesn’t cost enough. If the cost is right but the design doesn’t work, you don’t have a viable offering.

Before a design can be accused of having too much material and labor costs, it must be able to meet its functional specifications. Before that is accomplished, it’s likely there’s not enough material and labor in the design and more must be added to meet the functional specifications. In that way, it likely doesn’t cost enough. If the cost is right but the design doesn’t work, you don’t have a viable offering.

Before the low-cost manufacturing process can be chosen, the design must be able to do what customers need it to do. If the design does not yet meet its functional specification, it will change and evolve until it can. And once that is accomplished, low-cost manufacturing processes can be selected that fit with the design. Sure, the design might be able to be subtly adapted to fit the manufacturing process, but only as much as it preserves the design’s ability to meet its functional requirements. If you have a low-cost manufacturing process but the design doesn’t meet the specifications, you don’t have anything to sell.

Before a product can function robustly over a wide range of operating conditions, the prototype design must be able to meet the functional requirements at nominal operating conditions. If you’re trying to improve robustness before it has worked the first time, your work is out of sequence.

Before you can predict when the project will be completed, the design must be able to meet its functional requirements. Before that, there’s no way to predict when the product will launch. If you advertise the project completion date before the design is able to meet the functional requirements, you’re guessing on the date.

When your existing customers buy an upgrade package, it’s because the upgrade functions better. If the upgrade didn’t work better, customers wouldn’t buy it.

When your existing customers replace the old product they bought from you with the new one you just launched, it’s because the new one works better. If the new one didn’t work better, customers wouldn’t buy it.

Function first, no exceptions.

Image credit — Mrs Airwolfhound

When You Want To Make A Difference

When you want to make a difference, put your whole self out there.

When you want to make a difference, put your whole self out there.

When you want to make a difference, tell your truth.

When you want to make a difference, invest in people.

When you want to make a difference, play the long game.

When you want to make a difference, do your homework.

When you want to make a difference, buy lunch.

When you want to make a difference, let others in.

When you want to make a difference, be real.

When you want to make a difference, listen.

When you want to make a difference, choose a side.

When you want to make a difference, don’t take things personally.

When you want to make a difference, confide in others.

When you want to make a difference, send a text out of the blue.

And when you want to make a difference for yourself, make a difference for others.

Image credit – Tambako The Jaguar

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski