Posts Tagged ‘Lessons Learned’

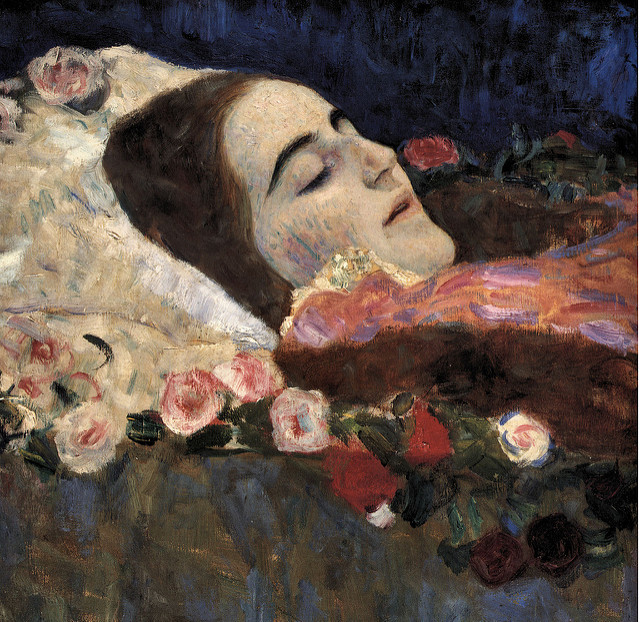

Progress is powered by people.

People ask why.

People buy products from people.

The right people turn activity into progress.

People want to make a difference, and they do.

People have biases which bring a richer understanding.

People use judgement – that’s why robots don’t run projects.

People recognize when the rules don’t apply and act accordingly.

Business models are an interconnected collection of people processes.

The simplest processes require judgement, that’s why they’re run by people.

People don’t like good service, they like effective interaction with other people.

People are the power behind the tools. (I never met a hammer that swung itself.)

Progress is powered by people.

Image credit – las – intially

How To Allocate Resources

How a company allocates its resources defines its strategy. But it’s tricky business to allocate resources in a way that makes the most of the existing products, services and business models yet accomplishes what’s needed to create the future.

How a company allocates its resources defines its strategy. But it’s tricky business to allocate resources in a way that makes the most of the existing products, services and business models yet accomplishes what’s needed to create the future.

To strike the right balance, and before any decisions on specific projects, allocate the desired spending into three buckets – short, medium and long. Or, if you prefer, Horizon 1, 2 and 3. Use the business objectives to set the weighting. Then, sit next to the CFO for a couple days and allocate last year’s actual spending to the three buckets and compare the actuals with how resources will be allocated going forward. Define the number of people who will work on short, medium and long and how many will move from one bucket to another.

To get the balance right, short term projects are judged relative to short term projects, medium term projects are judged relative to medium term projects and the long term ones are judged against their long term peers. Long term projects cannot be staffed at the expense of short term projects and medium term projects cannot take resources from long term projects. To get the balance right, those are the rules.

To choose the best projects within each bucket, clarity and constraints are more important than ROI. Here are some questions to improve clarity and define the constraints.

How will the customer benefit? It’s best to show the customer using the product or service or experiencing the new business model. Use a hand sketch and few, if any, words. Use one page.

How is it different? In the hand sketch above, draw the novel (different) elements in red.

Who is the new customer? Define where they live, the language they speak and how they get the job done today.

Are there regional constraints? Infrastructure gaps, such as electricity, water, transportation are deal breakers. Language gaps can be big problems, so can regulatory, legal and cultural constraints. If a regional constraint cannot be overcome, do something else.

How will your company make money? Use this formula: (price – cost) x volume. But, be clear about the size of the market today and the size it could be in five years.

How will you make, sell and service it? Include in the cost of the project the cost to overcome organizational capacity/capability constraints. If cost (or time) to close the gaps is prohibitive, do something else.

How will the business model change? If it won’t, strongly consider a different project.

If the investigations show the project is worthwhile, how would you staff the project and when? This is an important one. If the project would be a winner, but there is no one to work on it, do something else. Or, consider stopping a bad project to start the good one.

There’s usually a general tendency to move medium term resources to short term projects and skimp on long term projects. Be respectful of the newly-minted resource balance defined at the start and don’t choose a project from one bucket over a project from another. And don’t get carried away with ROI measured to three significant figures, rather, hold onto the fact that an insurmountable constraint reduces ROI to zero.

And staff projects fully. Partially-staffed projects set expectations that good things are happening, but they never come to be.

Image credit – john curley

Channel your inner sea captain.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

When it’s time for new work, the best and smartest get in a small room to figure out what to do. The process is pretty simple: define a new destination, and, to know when they journey is over, define what it looks like to live there. Define the idealized future state and define the work to get there. Turn on the GPS, enter the destination and follow the instructions of the computerized voice.

But with new work, the GPS analogy is less than helpful. Because the work is new, there’s no telling exactly where the destination is, or whether it exists at all. No one has sold a product like the one described in the idealized future state. At this stage, the product definition is wrong. So, set your course heading for South America though the destination may turn out to be Europe. No matter, it’s time to make progress, so get in the car and stomp the accelerator.

But with new work there is no map. It’s never been done before. Though unskillful, the first approach is to use the old map for the new territory. That’s like using map data from 1928 in your GPS. The computer voice will tell you to take a right, but that cart path no longer exists. The GPS calls out instructions that don’t match the street signs and highway numbers you see through the windshield. When the GPS disagrees with what you see with your eyeballs, the map is wrong. It’s time to toss the GPS and believe the territory.

With new work, it’s not the destination that’s important, the current location is most important. The old sea captains knew this. Site the stars, mark the time, and set a course heading. Sail for all your worth until the starts return and as soon as possible re-locate the ship, set a new heading and repeat. The course heading depends more on location than destination. If the ship is east of the West Indies, it’s best to sail west, and if the ship is to the north, it’s best to sail south. Same destination, different course heading.

When the work is new, through away the old maps and the GPS and channel your inner sea caption. Position yourself with the stars, site the landmarks with your telescope, feel the wind in your face and use your best judgement to set the course heading. And as soon as you can, repeat.

Image credit – Timo Gufler.

Stop bad project and start good ones.

At the most basic level, business is about allocating resources to the best projects and executing those projects well. Said another way, business is about deciding what to work on and then working effectively. But how to go about deciding what to work on? Here is a cascade of questions to start you on your journey.

At the most basic level, business is about allocating resources to the best projects and executing those projects well. Said another way, business is about deciding what to work on and then working effectively. But how to go about deciding what to work on? Here is a cascade of questions to start you on your journey.

What are your company’s guiding principles? Why does it exist? How does it want to go about its life? These questions create context from which to answer the questions that follow. Once defined, all your actions should align with your context.

How has the business environment changed? This is a big one. Everything is impermanent. Change is the status quo. What worked last time won’t work this time. Your success is your enemy because it stunts intentions to work on new things. Define new lines of customer goodness your competitors have developed; define how their technologies have increased performance; search YouTube to see the nascent technologies that will displace you; put yourself two years in the future where your customers will pay half what they pay today. These answers, too, define the context for the questions that follow.

What are you working on? Define your fully-staffed projects. Distill each to a single page. Do they provide new customer value? Are the projects aligned with your company’s guiding principles? For those that don’t, stop them. How do your fully-staffed projects compare to the trajectory of your competitors’ offerings? For those that compare poorly, stop them.

For projects that remain, do they meet your business objectives? If yes, put your head down and execute. If no, do you have better projects? If yes, move the freed up resources (from the stopped projects) onto the new projects. Do it now. If you don’t have better projects, find some. Use lines of evolution for technological systems to figure out what’s next, define new projects and move the resources. Do it now.

The best leading indicator of innovation is your portfolio of fully-staffed projects. Where other companies argue and complain about organizational structure, move your best resources to your best projects and execute. Where other companies use politics to trump logic, move your best resources to your best projects and execute. Where other successful companies hold on to tired business models and do-what-we-did-last-time projects, move your best resources to your best projects and execute.

Be ruthless with your projects. Stop the bad ones and start some good ones. Be clear about what your projects will deliver – define the novel customer value and the technical work to get there. Use one page for each. If you can’t define the novel customer value with a simple cartoon, it’s because there is none. And if you can’t define how you’ll get there with a hand sketch, it’s because you don’t know how.

Define your company’s purpose and use that to decide what to work on. If a project is misaligned, kill it. If a project is boring, don’t bother. If it’s been done before, don’t do it. And if you know how it will go, do something else.

If you’re not changing, you’re dying.

Image credit – David Flam

The Chief Innovation Mascot

I don’t believe the role of Chief Innovation Officer has a place in today’s organizations. Today, it should be about doing the right new work to create value. That work, I believe, should be done within the organization as a whole or within dedicated teams within the organization. That work, I believe, cannot be done by the Chief Innovation Officer because the organizational capability and capacity under their direct control is hollow.

I don’t believe the role of Chief Innovation Officer has a place in today’s organizations. Today, it should be about doing the right new work to create value. That work, I believe, should be done within the organization as a whole or within dedicated teams within the organization. That work, I believe, cannot be done by the Chief Innovation Officer because the organizational capability and capacity under their direct control is hollow.

Chief Innovation Officers don’t have the resources under their control to do innovation work. That’s the fundamental problem. Without the resources to invent, validate and commercialize, the Chief Innovation Officer is really the Chief Innovation Mascot- an advocate for the cause who wears the costume but doesn’t have direct control over the work.

Companies need to stop talking about innovation as a word and start doing the work that creates new products and services for new customers in markets. It all starts with the company’s business objectives (profitability goals) and an evaluation of existing projects to see if they’ll meet those objectives. If they will, then it’s about executing those projects. (The Chief Innovation Officer can’t help here because that requires operational resources.) If they won’t, it’s about defining and executing new projects that deliver new value to new customers. (Again, this is work for deep subject matter experts across multiple organizations, none of which work for the Chief Innovation Officer.)

To create a non-biased view of the projects, identify lines of customer goodness, measure the rate of change of that goodness, assess the underpinning technologies (momentum, trajectory, maturity and completeness) and define the trajectory of the commercial space. This requires significant resource commitments from marketing, engineering and sales, resource commitments The Chief Innovation Officer can’t commit. Cajole and prod for resources, yes. Allocate them, no.

With a clear-eyed view of their projects and the new-found realization that their projects won’t cut it, companies can strengthen their resolve to do new work in new ways. The realization of an immanent shortfall in profits is the only think powerful enough to cause the company to change course. The company then spends the time to create new projects and (here’s the kicker) moves resources to the new projects. The most articulate and persuasive Chief Innovation Officer can’t change an organization’s direction like that, nor can they move the resources.

To me it’s not about the Chief Innovation Officer. To me it’s about creating the causes and conditions for novel work; creating organizational capability and capacity to do the novel work; and applying resources to the novel work so it’s done effectively. And, yes, there are tools and methods to do that work well, but all that is secondary to allocating organizational capacity to do new work in new ways.

When Chief Innovation Officer are held accountable for “innovation objectives,” they fail because they’re beholden to the leaders who control the resources. (That’s why their tenures are short.) And even if they did meet the innovation objectives, the company would not increase it’s profits because innovation objectives don’t pay the bills. The leaders that control the resources must be held accountable for profitability objectives and they must be supported along the way by people that know how to do new work in new ways.

Let’s stop talking about innovation and the officers that are supposed to do it, and let’s start talking about new products and new services that deliver new value to new customers in new markets.

Image credit – Neon Tommy

If you don’t know the critical path, you don’t know very much.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Once you have a project to work on, it’s always a challenge to choose the first task. And once finished with the first task, the next hardest thing is to figure out the next next task.

Two words to live by: Critical Path.

By definition, the next task to work on is the next task on the critical path. How do you tell if the task is on the critical path? When you are late by one day on a critical path task, the project, as a whole, will finish a day late. If you are late by one day and the project won’t be delayed, the task is not on the critical path and you shouldn’t work on it.

Rule 1: If you can’t work the critical path, don’t work on anything.

Working on a non-critical path task is worse than working on nothing. Working on a non-critical path task is like waiting with perspiration. It’s worse than activity without progress. Resources are consumed on unnecessary tasks and the resulting work creates extra constraints on future work, all in the name of leveraging the work you shouldn’t have done in the first place.

How to spot the critical path? If a similar project has been done before, ask the project manager what the critical path was for that project. Then listen, because that’s the critical path. If your project is similar to a previous project except with some incremental newness, the newness is on the critical path.

Rule 2: Newness, by definition, is on the critical path.

But as the level of newness increases, it’s more difficult for project managers to tell the critical path from work that should wait. If you’re the right project manager, even for projects with significant newness, you are able to feel the critical path in your chest. When you’re the right project manager, you can walk through the cubicles and your body is drawn to the critical path like a divining rod. When you’re the right project manager and someone in another building is late on their critical path task, you somehow unknowingly end up getting a haircut at the same time and offering them the resources they need to get back on track. When you’re the right project manager, the universe notifies you when the critical path has gone critical.

Rule 3: The only way to be the right project manager is to run a lot of projects and read a lot. (I prefer historical fiction and biographies.)

Not all newness is created equal. If the project won’t launch unless the newness is wrestled to the ground, that’s level 5 newness. Stop everything, clear the decks, and get after it until it succumbs to your diligence. If the product won’t sell without the newness, that’s level 5 and you should behave accordingly. If the newness causes the product to cost a bit more than expected, but the project will still sell like nobody’s business, that’s level 2. Launch it and cost reduce it later. If no one will notice if the newness doesn’t make it into the product, that’s level 0 newness. (Actually, it’s not newness at all, it’s unneeded complexity.) Don’t put in the product and don’t bother telling anyone.

Rule 4: The newness you’re afraid of isn’t the newness you should be afraid of.

A good project plan starts with a good understanding of the newness. Then, the right project work is defined to make sure the newness gets the attention it deserves. The problem isn’t the newness you know, the problem is the unknown consequence of newness as it ripples through the commercialization engine. New product functionality gets engineering attention until it’s run to ground. But what if the newness ripples into new materials that can’t be made or new assembly methods that don’t exist? What if the new materials are banned substances? What if your multi-million dollar test stations don’t have the capability to accommodate the new functionality? What if the value proposition is new and your sales team doesn’t know how to sell it? What if the newness requires a new distribution channel you don’t have? What if your service organization doesn’t have the ability to diagnose a failure of the new newness?

Rule 5: The only way to develop the capability to handle newness is to pair a soon-to-be great project manager with an already great project manager.

It may sound like an inefficient way to solve the problem, but pairing the two project managers is a lot more efficient than letting a soon-to-be great project manager crash and burn. After an inexperienced project manager runs a project into the ground, what’s the first thing you do? You bring in a great project manager to get the project back on track and keep them in the saddle until the product launches. Why not assume the wheels will fall off unless you put a pro alongside the high potential talent?

Rule 6: When your best project managers tell you they need resources, give them what they ask for.

If you want to deliver new value to new customs there’s no better way than to develop good project managers. A good project manager instinctively knows the critical path; they know how the work is done; they know to unwind situations that needs to be unwound; they have the personal relationships to get things done when no one else can; because they are trusted, they can get people to bend (and sometimes break) the rules and feel good doing it; and they know what they need to successfully launch the product.

If you don’t know your critical path, you don’t know very much. And if your project managers don’t know the critical path, you should stop what you’re doing, pull hard on the emergency break with both hands and don’t release it until you know they know.

Image credit – Patrick Emerson

Battling the Dark Arts of Productivity and Accountability

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

How did you get to where you are? Was it a series of well-thought-out decisions or a million small, non-decisions that stacked up while you weren’t paying attention? Is this where you thought you’d end up? What do you think about where you are?

It takes great discipline to make time to evaluate your life’s trajectory, and with today’s pace it’s almost impossible. Every day it’s a battle to do more than yesterday. Nothing is good enough unless it’s 10% better than last time, and once it’s better, it’s no longer good enough. Efficiency is worked until it reaches 100%, then it’s redefined to start the game again. No waste is too small to eliminate. In business there’s no counterbalance to the economists’ false promise of never-ending growth, unless you provide it for yourself.

If you make the time, it’s easy to plan your day and your week. But if you don’t make the time, it’s impossible. And it’s the same for the longer term – if you make the time to think about what you want to achieve, you have a better chance of achieving it – but it’s more difficult to make the time. Before you can make the time to step back and take look at the landscape, you’ve got to be aware that it’s important to do and you’re not doing it.

Providing yourself the necessary counterbalance is good for you and your family, and it’s even better for business. When you take a step back and slow your pace from sprint to marathon, you are happier and healthier and your work is better. When scout the horizon and realize you and your work are aligned, you feel better about the work and, therefore, you feel better about yourself. You’re a better person, partner and parent. And your work is better. When the work fits, everything is better.

Sometimes, people know their work doesn’t fit and purposefully don’t take a step back because it’s too scary to acknowledge there’s a problem. But burying your head doesn’t fix things. If you know you’re out of balance, the best thing to do is admit it and start a dialog with yourself and your boss. It won’t get better immediately, but you’ll feel better immediately. But most of the time, people don’t make time to take a step back because of the blistering pace of the work. There’s simply no time to think about the future. What’s missing is a weapon to battle the black arts of productivity and accountability.

The only thing powerful enough to counterbalance the forces of darkness is the very weapon we use to create the disease of hyper-productivity – the shared calendar (MS Calendar, Google Calendar). Open up the software, choose your day, choose your time and set up a one hour weekly meeting with yourself. Attendees: you. Agenda: take a couple deep breaths, relax and think. Change your settings so no one can see the meeting title and agenda and choose the color that makes people think the meeting is off-site. With your time blocked, you now have a reason to say no to other meetings. “Sorry, I can’t attend. I have a meeting.”

This simple mechanism is all you need.

No more excuses. Make the time for yourself. You’re worth it.

image credit :jovian (image modified)

The Yin and Yang of Work

Do good work and people will notice. Do work to get noticed and people will notice that too.

Do good work and people will notice. Do work to get noticed and people will notice that too.

Try to do good work and you’ll get ahead. Try to get ahead and you won’t.

If the work feels good while you’re doing it, it’s good work. If it doesn’t, it’s not.

If you watch the clock while you work, that says nothing about the clock.

When you surf the web at work, you’re not working. When you learn from blog posts, podcasts and TED talks, you are.

Using social media at work is good for business, except when it isn’t.

When you feel you don’t have the authority, you don’t. If you think you need authority, you shouldn’t.

When people seek your guidance you have something far more powerful than authority, you have trust.

Don’t pine for authority, earn the right to influence.

Influence is to authority as trust is to control.

Personal relationships are more powerful than org charts. Work the relationships, not the org chart.

There’s no reason to change right up until there’s a good reason. It may be too late, but at least you’ll have a reason.

Holding on to what you have comes at the expense of creating the future.

As a leader don’t take credit, take responsibility.

And when in doubt, try something.

Image credit — Peter Clark

Your Words Make All The Difference.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

Sometimes people are unskillful with their words, and what they say can have multiple interpretations. But, though you don’t have control over their words, you do have control over how you interpret them. And the translation you choose makes all the difference. On the flipside, when you choose your words skillfully they can have a singular translation. And that, too, makes all the difference. Here are some examples.

It can’t be done. Translations: 1) We’ve never tried it and we don’t know how to go about it. 2) We know you’ll not give us the time and the resources to do it right, and because of that, we won’t be successful. 3) Wow. I like that idea, but we’re already so overloaded. Do you think we can talk about that in the second half of the year?

We tried that but it didn’t work. Translations: 1) Twelve years ago someone who made a prototype and it worked pretty well. But, she wasn’t given the time to take it to the next level and the project was abandoned. 2) We all think that’s a wonderful idea and really want to work on it, but we’re too busy to think about that. If I come clean, will you give me the resources to do it right?

Why didn’t you follow the best practice? Translations: 1) I’m afraid of the uncertainty around this innovation work and I’ve heard best practices can reduce risk. 2) I don’t really know what I’m talking about, but this seems like a safe question to ask without tipping my hand. 3) I want to make a difference at the company, but I’ve never been part of a project with so much newness. Can you teach me?

That’s not how we do it. Translations: 1) I’ve always done it that way, and thinking about doing it differently scares me. 2) Though the process is clunky, we’ve been told to follow it. And I don’t want to get in trouble. 3) That sounds like a good idea, but I don’t have the time to think through the potential implications to our customers.

What are you working on? Translation: I’m interested in what you’re working on because I care about you.

Can I help you? Translation: You’ve helped me in the past and I see you’re in a tough situation. I care about you. What can I do to help?

Good job. Translation: I want to positively reinforce your good work in front of everyone because, well, you did good work.

That’s a good idea. Translation: I think highly of you, I like that you stuck out your neck, and I hope you do it regularly.

I need help. Translation: I know you are highly capable and I trust you. I’m in a tight spot here. Can you help me?

Thank you. Translation: You were helpful and I appreciate it. Thank you.

How you choose your words and how you choose to assign meaning to others’ words make all the difference. Choose skillfully.

image credit — woodleywonderworks

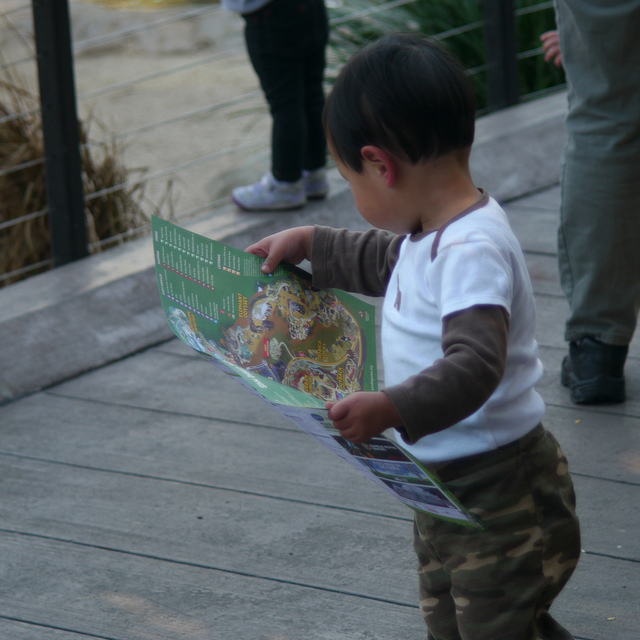

Don’t mentor. Develop young talent.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent understands technology far better than your senior leaders. And they don’t just know how it works, they know why people use it. And it’s not just social media. They know how to code, they know how to prototype (I think the call it hacking, or something like that.) and they know how things fit together. And they know what’s next. But they don’t know how to get things done within your organization.

Mentoring isn’t the right word. It’s a tired word without meaning, and we’ve demonstrated we care about it only from a compliance standpoint and not a content standpoint. The mentorship checklist – set up regular meetings, meet infrequently without an agenda, lie it die a slow death and then declare compliance. Nurturing is a better word, but it has connotations of taking care. Parenting captures the essence of the work, but it doesn’t fit with the language of companies. But that may not be so bad, because the work doesn’t fit with the operations companies.

In the short term it’s inefficient to spend precious leadership bandwidth on young talent, but in the long run, it’s the only way to go. Just as the yardwork goes more slowly when your kids help, the next time it’s a bit faster. But the real benefit, the unquantifiable benefit, is the pure joy of spending time with irreverent, energetic, idealistic young people. Yes, there’s less productivity (fewer leaves raked per hour), but that’s not what it’s about. There’s growth, increased capability and shared experience that will set up the next lesson.

The biggest mistake is to come up with special “mentorship projects”. Adding work for the sake of growing talent is wrong on so many levels. Instead, help them with the work they’re expected to do. Dig in. Help them. Contribute to their projects. Go to their meetings. Provide technical guidance. Look ahead for potential problems and tell them they are looming over the horizon. Let them make the decisions. Let them choose the path, but run ahead and make sure they negotiate the corner. If they’re going to make it, let them scoot through without them seeing you. If they’re going to crash, grab the wheel and negotiate the corner with them. Then, when things have calmed down, tell them why you stepped in.

Your children watch you. They watch how you interact with your spouse; they watch how you handle stressful situations; they watch how you treat other children; they listen to what you say to them; they listen to how you say it. And when the words disagree with the unsaid sentiment, they believe the sentiment. Your children know you by your actions. You are transparent to them. They know everything about you. They know why you do things and they know what you stand for. And young talent is no different.

There is nothing more invigorating than a bright, young person willing to dig in and make a difference. Their passion is priceless. And as much as you are helping them, they are helping you. They spark new thinking; they help you see the implicit assumptions you’ve left untested for too long and then naively stomp on them and give you a save-face way to revisit your old thinking. When the toddler learns to walk, even the grandparents spring to life and spryly support them step-by-step.

Don’t call it parenting, but behave like one. Take the time to form the close relationships that transcend the generational divide. Make it personal, because it is. And when you have too much to do and too little time to invest in young talent, do it anyway. Do it for them or do it for the company, but do it.

But in the end, do it for the right reason, the selfish reason – because it the best thing for you.

Image credit – mliu92

Step-Wise Learning

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

At every meeting you have a chance to move things forward or hold them back. When a new idea is first introduced it’s bare-naked. In its prenatal state, it’s wobbly and can’t stand on its own and is vulnerable to attack. But since it’s not yet developed, it’s impressionable and willing to evolve into what it could be. With the right help it can go either way – die a swift death or sprout into something magical.

Early in gestation, the most worthy ideas don’t look that way. They’re ugly, ill-formed, angry or threatening. Or, they’re playful, silly or absurd. Depending on your outlook, they can be a member of either camp. And as your outlook changes, they can jump from one camp to the other. Or, they can sit with one leg in each. But none of that is about the idea, it’s all about you. The idea isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a reflection of you. The idea is nothing until you attach your feelings to it. Whether it lives or dies depends on you.

Are you looking for reasons to say yes or reasons to say no?

On the surface, everyone in the organization looks like they’re fully booked with more smart goals than they can digest and have more deliverables than they swallow, but that’s not the case. Though it looks like there’s no room for new ideas, there’s plenty of capacity to chew on new ideas if the team decides they want to. Every team can spare and hour or two a week for the right ideas. The only real question is do they want to?

If someone shows interest and initiative, it’s important to support their idea. The smallest acceptable investment is a follow-on question that positively reinforces the behavior. “That’s interesting, tell me more.” sends the right message. Next, “How do you think we should test the idea?” makes it clear you are willing to take the next step. If they can’t think of a way to test it, help them come up with a small, resource-lite experiment. And if they respond with a five year plan and multi-million dollar investment, suggest a small experiment to demonstrate worthiness of the idea. Sometimes it’s a thought experiment, sometimes it’s a discussion with a customer and sometimes it’s a prototype, but it’s always small. Regardless of the idea, there’s always room for a small experiment.

Like a staircase, a series of small experiments build on each other to create big learning. Each step is manageable – each investment is tolerable and each misstep is survivable – and with each experiment the learning objective is the same: Is the new idea worthy of taking the next step? It’s a step-wise set of decisions to allocate resources on the right work to increase learning. And after starting in the basement, with step-by-step experimentation and flight-by-flight investment, you find yourself on the fifth floor.

This is about changing behavior and learning. Behavior doesn’t change overnight, it changes day-by-day, step-by-step. And it’s the same for learning – it builds on what was learned yesterday. And as long at the experiment is small, there can be no missteps. And it doesn’t matter what the first experiment is all about, as long as you take the first step.

Your team will recognize your new behavior because it respectful of their ideas. And when you respect their ideas, you respect them. Soon enough you will have a team that stands taller and runs small experiments on their own. Their experiments will grow bolder and their learning will curve will steepen. Then, you’ll struggle to keep up with them, and you’ll have them right where you want them.

image credit — Rob Warde

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski