Posts Tagged ‘Lessons Learned’

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

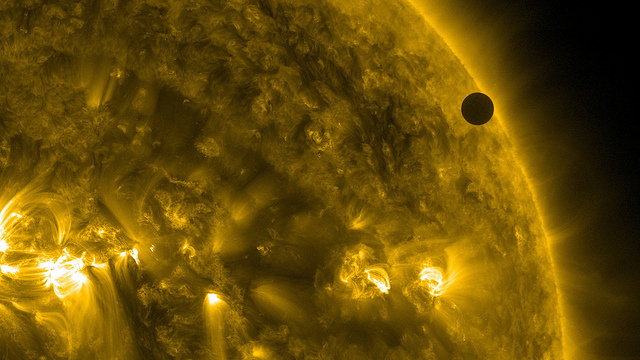

Image credit: NASA Goddard

How To Innovate Within a Successful Company

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

You can’t compete with the successful business teams that pay the bills because paying the bills is too important. No one in their right mind should get in the way of paying them. And if you do put yourself in the way of the freight train that pays the bills you’ll get run over. If you want to live to fight another day, don’t do it.

If an established business has been growing three percent year-on-year, expect them to grow three percent next year. Sure, you can lather them in investment, but expect three and a half percent. And if they promise six percent, don’t believe them. In fairness, they truly expect they can grow six percent, but only because they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid.

Rule 1: If they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid, don’t believe them.

Without a cataclysmic problem that threatens the very existence of a successful company, it’s almost impossible to innovate within its four walls. If there’s no impending cataclysm, you have two choices: leave the four walls or don’t innovate.

It’s great to work at successful company because it has a recipe that worked. And it sucks to work at a successful company because everyone thinks that tired old recipe will work for the next ten years. Whether it will work for the next ten or it won’t, it’s still a miserable place to work if you want to try something new. Yes, I said miserable.

What’s the one thing a successful company needs? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo. What’s the one thing a successful company does not tolerate? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo.

Some experts recommend leveraging (borrowing) resources from the established businesses and using them to innovate. If the established business catches wind that their borrowed resources will be used to displace the status quo, the resources will mysteriously disappear before the innovation project can start. Don’t try to borrow resources from established businesses and don’t believe the experts.

Instead of competing with established businesses for resources, resources for innovation should be allocated separately. Decide how much to spend on innovation and allocate the resources accordingly. And if the established businesses cry foul, let them.

Instead of borrowing resources from established businesses to innovate, increase funding to the innovation units and let them buy resources from outside companies. Let them pay companies to verify the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP); let them pay outside companies to design the new product; let them pay outside companies to manufacture the new product; and let them pay outside companies to sell it. Sure, it will cost money, but with that money you will have resources that put their all into the design, manufacture and sale of the innovative new offering. All-in-all, it’s well worth the money.

Don’t fall into the trap of sharing resources, especially if the sharing is between established businesses and the innovative teams that are charged with displacing them. And don’t fall into the efficiency trap. Established businesses need efficiency, but innovative teams need effectiveness.

It’s not impossible to innovate within a successful company, but it is difficult. To make it easier, error on the side of doing innovation outside the four walls of success. It may be more expensive, but it will be far more effective. And it will be faster. Resources borrowed from other teams work the way they worked last time. And if they are borrowed from a successful team, they will work like a successful team. They will work with loss aversion. Instead of working to bring something to life they will work to prevent loss of what worked last time. And when doing work that’s new, that’s the wrong way to work.

The best way I know to do innovation within a successful company is to do it outside the successful company.

Image credit – David Doe

Cubicles – just say no.

Whether it’s placing machine tools on the factory floor or designing work spaces for people that work at the company, the number one guiding metric is resources per square foot. If you’re placing machine tools, this metric causes the machines to be stacked closely together, where the space between them is minimized, access to the machines is minimized, and the aisles are the smallest they can be. The result – the number of machines per square foot is maximized.

And though there has been talk of workplaces that promote effective interactions and creativity, the primary metric is still people per square foot. Don’t believe me? I have one word for you – cubicles. Cubicles are the design solution of choice when you want to pack the most people into the smallest area.

Here’s a test. At your next team meeting, ask people to raise their hand if they hate working in a cubicle. I rest my case.

With cubicles, it’s the worst of both worlds. There is none of the benefit of an office and none of the benefit of collaborative environment. They are half of neither.

What is one of Dilbert’s favorite topic? Cubicles.

If no one likes them, why do we still have them? If you want quiet, cubicles are the wrong answer. If you want effective collaboration, cubicles are the wrong answer. If everyone hates them, why do we still have them?

When people need to do deep work, they stay home so they can have peace and quiet. When people they want to concentrate, they avoid cubicles at all costs. When you need to focus, you need quiet. And the best way to get quiet is with four walls and a door. Some would call that and office, but those are passe. And in some cases, they are outlawed. In either case, they are the best way to get some quiet time. And, as a side benefit, they also block interruptions.

Best way for people to interact is face-to-face. And in order to interact at way, they’ve got to be in the same place at the same time. Sure spontaneous interactions are good, but it’s far better to facilitate interactions with a fixed schedule. Like with a bus stop schedule, people know where to be and when. In that way, many people can come together efficiently and effectively and the number of interactions increases dramatically. So why not set up planned interactions at ten in the morning and two in the afternoon?

I propose a new metric for facilities design – number of good ideas per square foot. Good ideas require deep thought, so quiet is important. And good ideas require respectful interaction with others, so interactions are important.

I’m not exactly sure what a facility must look like to maximize the number of good ideas per square foot, but I do know it has no cubicles.

Image credit – Tim Patterson

How To Design

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What does it do? A complete set of functional requirements is difficult to create, so don’t start with a complete set. Use your new knowledge of the top customer needs to define and prioritize the top functional requirements (think three to five). Once tightly formalized, these requirements will guide the more detailed work that follows. The functional requirements are mapped to elements of the design, or design parameters, that will bring the functions to life. But before that, ask yourself if a check-in with some potential customers is warranted. Sometimes it is, but at these early stages it’s may best to wait until you have something tangible to show customers.

What does it look like? The design parameters define the physical elements of the design that ultimately create the functionality customers will buy. The design parameters define shape of the physical elements, the materials they’re made from and the interaction of the elements. It’s best if one design parameter controls a single functional requirement so the functions can be dialed in independently. At this early concept phase, a sketch or CAD model can be created and reviewed with customers. You may learn you’re off track or you may learn you’re way off track, but either way, you’ll learn how the design must change. But before that, take a little time to think through how the product will be made.

How to make it? The process variables define the elements of the manufacturing process that make the right shapes from the right materials. Sometimes the elements of the design (design parameters) fit the process variables nicely, but often the design parameters must be changed or rearranged to fit the process. Postpone this mapping at your peril! Once you show a customer a concept, some design parameters are locked down, and if those elements of the design don’t fit the process you’ll be stuck with high costs and defects.

How to sell it? The goodness of the design must be translated into language that fits the customer. Create a single page sales tool that describes their needs and how the new functionality satisfies them. And include a digital image of the concept and add it to the one-pager. Show document to the customer and listen. The customer feedback will cause you to revisit the functional requirements, design parameters and process variables. And that’s how it’s supposed to go.

Though I described this process in a linear way, nothing about this process is linear. Because the domains are mapped to each other, changes in one domain ripple through the others. Change a material and the functionality changes and so do the process variables needed to make it. Change the process and the shapes must change which, in turn, change the functionality.

But changes to the customer needs are far more problematic, if not cataclysmic. Change the customer needs and all the domains change. All of them. And the domains don’t change subtly, they get flipped on their heads. A change to a customer need is an avalanche that sweeps away much of the work that’s been done to date. With a change to a customer need, new functions must be created from scratch and old design elements must culled. And no one knows what the what the new shapes will be or how to make them.

You can’t hold off on the design work until all the customer needs are locked down. You’ve got to start with partial knowledge. But, you can check in regularly with customers and show them early designs. And you can even show them concept sketches.

And when they give you feedback, listen.

Image credit – Worcester Wired

Is your tank empty?

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

We’re pretty good at remembering that a car’s tank is finite. At the start of the morning commute, the car’s fuel gauge gives a clear reading of the fuel level and we do the calculation to determine if we can make it or we need to stop for fuel. And we do the same thing in the evening – look at the gauge, determine if we need fuel and act accordingly. Rarely we run the car out of fuel because the car continuously monitors and displays the fuel level and we know there are consequences if we run out of fuel.

We’re not so good at remembering our personal tanks are finite. At the start of the day, there are no objective fuel gauges to display our internal fuel levels. The only calculation we make – if we can make it out of bed we have enough fuel for the day. We need to do better than that.

Our bodies do have fuel gages of sorts. When our fuel is low we can be irritable, we can have poor concentration, we can be easily distracted. Though these gages are challenging to see and difficult to interpret, they can be used effectively if we slow down and be in our bodies. The most troubling part has nothing to do with our internal fuel gages. Most troubling is we fail to respect their low fuel warnings even when we do recognize them. It’s like we don’t acknowledge our tanks are finite.

We don’t think our cars are flawed because their fuel tanks run low as we drive. Yet, we see the finite nature of our internal fuel tanks as a sign of weakness. Why is that? Rationally, we know all fuel tanks are finite and their fuel level drops with activity. But, in the moment, when are tanks are low, we think something is wrong with us, we think we’re not whole, we think less of ourselves.

When your tank is low, don’t curse, don’t blame, don’t feel sorry and don’t judge. It’s okay. That’s what tanks do.

A simple rule for all empty tanks – put fuel in them.

Image credit – Hamed Saber

The people part is the hardest part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

The toughest part of all things is the people part.

Hold on to being right and all you’ll be is right. Transcend rightness and get ready for greatness.

Embrace hubris and there’s no room for truth. Embrace humbleness and everyone can get real.

Judge yourself and others will pile on. Praise others and they will align with you.

Expect your ideas to carry the day and they won’t. Put your ideas out there lightly and ask for feedback and your ideas will grow legs.

Fight to be right and all you’ll get is a bent nose and bloody knuckles. Empathize and the world is a different place.

Expect your plan to control things and the universe will have its way with you. See your plan as a loosely coupled set of assumptions and the universe will still have its way with you.

Argue and you’ll backslide. Appreciate and you’ll ratchet forward.

See the two bad bricks in the wall and life is hard. See the other nine hundred and ninety-eight and everything gets lighter.

Hold onto success and all you get is rope burns. Let go of what worked and the next big thing will find you.

Strive and get tired. Thrive and energize others.

The people part may be the toughest part, but it’s the part that really matters.

Image credit — Arian Zwegers

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

Don’t trust your gut, run the test.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

The first step is to define the idea/concept you want to validate or invalidate. The best way is to complete one of these two sentences: I want to learn that [type your idea here] is true. Or, I want to learn that [enter your idea here] is false.

Next, ask yourself this question: What information do I need to validate (or invalidate) [type your idea here]? Write down the information you need. In the engineering domain, this is straightforward: I need the temperature of this, the pressure of that, the force generated on part xyz or the time (in seconds) before the system catches fire. But for people-related ideas, things aren’t so straightforward. Some things you may want to know are: how much will you pay for this new thing, how many will you buy, on a scale of 1 to 5 how much do you like it?

Now the tough part – how will you judge pass or fail? What is the maximum acceptable temperature? What is the minimum pressure? What is the maximum force that can be tolerated? How many seconds must the system survive before catching fire? And for people: What is the minimum price that can support a viable business? How many must they buy before the company can prosper? And if they like it at level 3, it’s a go. And here’s the most importance sentence of the entire post:

The decision criteria must be defined BEFORE running the test.

If you wait to define the go/no-go criteria until after you run the test and review the data, you’ll adjust the decision criteria so you make the decision you wanted to make before running the test. If you’re not going to define the decision criteria before running the test, don’t bother running the test and follow your gut. Your decision will be a bad one, but at least you’ll save the time and money associated with the test.

And before running the test, define the test protocol. Think recipe in a cookbook: a pinch of this, a quart of that, mix it together and bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 40 minutes. The best protocols are simple and clear and result in the same sequence of events regardless of who runs the test. And make sure the measurement method is part of the protocol – use this thermocouple, use that pressure gauge, use the script to ask the questions about price and the number they’d buy.

And even with all this rigor, good judgement is still part of the equation. But the judgment is limited to questions like: did we follow the protocol? Did the measurement system function properly? Do the initial assumptions still hold? Did anything change since we defined the learning objective and defined the test protocol?

To create formal learning objectives, to write well-defined test protocols and to formalize the decision criteria before running the test require rigor, discipline, time and money. But, because the cost of making a bad decision is so high, the cost of running good tests is a bargain at twice the price.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Flight Center

A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski