Posts Tagged ‘Fear’

On Gumption

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Move from self-judging to self-loving. It makes a difference.

It’s never enough until you decide it’s enough. And when you do, you can be more beholden to yourself.

You already have what you’re looking for. Look inside.

Taking care of yourself isn’t selfish, it’s self-ful.

When in doubt, go outside.

You can’t believe in yourself without your consent.

Your well-being is your responsibility. And it’s time to be responsible.

When you move your body, your mind smiles.

With selfish, you take care of yourself at another’s expense. With self-ful, you take care of yourself because you’re full of self-love.

When in doubt, feel the doubt and do it anyway.

If you’re not taking care of yourself, understand what you’re putting in the way and then don’t do that anymore.

You can’t help others if you don’t take care of yourself.

If you struggle with taking care of yourself, pretend you’re someone else and do it for them.

Image credit — Ramón Portellano

You can’t innovate when…

Your company believes everything should always go as planned.

You still have to do your regular job.

The project’s completion date is disrespectful of the work content.

Your company doesn’t recognize the difference between complex and complicated.

The team is not given the tools, training, time and a teacher.

You’re asked to generate 500 ideas but you’re afraid no one will do anything with them.

You’re afraid to make a mistake.

You’re afraid you’ll be judged negatively.

You’re afraid to share unpleasant facts.

You’re afraid the status quo will be allowed to squash the new ideas, again.

You’re afraid the company’s proven recipe for success will stifle new thinking.

You’re afraid the project team will be staffed with a patchwork of part time resources.

You’re afraid you’ll have to compete for funding against the existing business units.

You’re afraid to build a functional prototype because the value proposition is poorly defined.

Project decisions are consensus-based.

Your company has been super profitable for a long time.

The project team does not believe in the project.

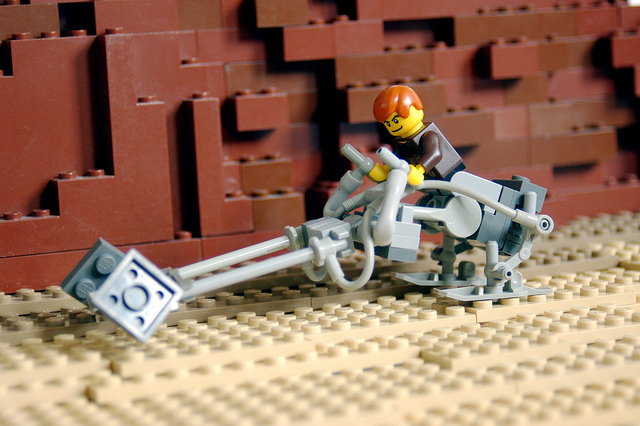

Image credit Vera & Gene-Christophe

Your response is your responsibility.

If you don’t want to go to work in the morning, there’s a reason. If’ you/re angry with how things go, there’s a reason. And if you you’re sad because of the way that people treat you, there’s a reason. But the reason has nothing to do with your work, how things are going or how people treat you. The reason has everything to do with your ego.

If you don’t want to go to work in the morning, there’s a reason. If’ you/re angry with how things go, there’s a reason. And if you you’re sad because of the way that people treat you, there’s a reason. But the reason has nothing to do with your work, how things are going or how people treat you. The reason has everything to do with your ego.

And your ego has everything to do with what you think of yourself and the identity you attach to yourself. If you don’t want to go to work, it’s because you don’t like what your work says about you or your image of your self. If you are angry with how things go, it’s because how things go says something about you that you don’t like. And if you’re sad about how people treat you, it’s because you think they may be right and you don’t like what that says about you.

The work is not responsible for your dislike of it. How things go is not responsible for your anger. And people that treat you badly are not responsible for your sadness. Your dislike is your responsibility, your anger is your responsibility and your sadness is your responsibility. And that’s because your response is your responsibility.

Don’t blame the work. Instead, look inside to understand how the work cuts against the grain of who you think you are. Don’t blame the things for going as they go. Instead, look inside to understand why those things don’t fit with your self-image. Don’t blame the people for how they treat you. Instead, look inside to understand why you think they may be right.

It’s easy to look outside and assign blame for your response. It’s the work’s fault, it’s the things’ fault, and it’s the people’s fault. But when you take responsibility for your response, when you own it, work gets better, things go better and people treat you better. Put simply, you take away their power to control how you feel and things get better.

And if work doesn’t get better, things don’t go better and people don’t treat you better, not to worry. Their responses are their responsibility.

Image credit Mrs. Gemstone

Being Right in the Right Way

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

Right doesn’t mean correct. And right doesn’t mean something else is wrong. When you have right view, it doesn’t mean you see things exactly right. It means you’re going about things in a way that’s right for the situation. It means your approach feels right to the people involved. It means you’re going about things with the right intention.

Now, like with any new idea, you’re obligated to formalize what you think is right and explain it to your peers. But, to be clear, you’re not looking for permission, you’re writing it down to help you understand what you think. When you try to present your thoughts, you’ll learn what you know and what you don’t. You’ll learn which words work and which don’t. You’ll learn right speech.

And you’ll find the potholes. And that’s why you present to your peers. They’ll be critical of the idea and respectful of you. They’ll tell you the truth because they know it’s better to iron out the details early and often. As a group, you’ll support each other. As a group, you’ll take the right action.

When ideas are introduced that are different, the organization will feel stress. Everyone wants to do a good job, yet there’s no agreement on the right way. Even though there’s stress, no one wants to create harm and everyone wants to behave ethically. It’s important to demonstrate compassion to yourself and others. The stress is natural, but it’s also natural to go about your livelihood in the right way.

But when the stakes are high and there’s no consensus on how to move forward, it’s not easy to hold onto the right mental state. The stress can cause us to delude ourselves into thinking things aren’t going well. But, letting the disagreement go unaddressed is unskillful, as it will only fester. It’s far more skillful to respectfully debate and discuss the disagreement. In that way, everyone makes the right effort to work things out.

Over time, the pattern of behavior can transition to a natural openness where ideas are shared freely. This becomes easier when we drop the mental habit of categorizing things into buckets we like and buckets we don’t. And it helps to maintain awareness of how things really are so we can strip away our subjective options. In this case, mindfulness is the right way to go.

None of this is easy. Our minds are constantly distracted by competing demands, growing to-do lists and organizational complexities of the work. Without dedicated practice, our minds can get lost in a flurry of thoughts of our own creation. To make it work, we’ve got to maintain a heightened alertness to our mental state and that takes the right concentration.

There’s nothing new here, but this well-worn path has merit.

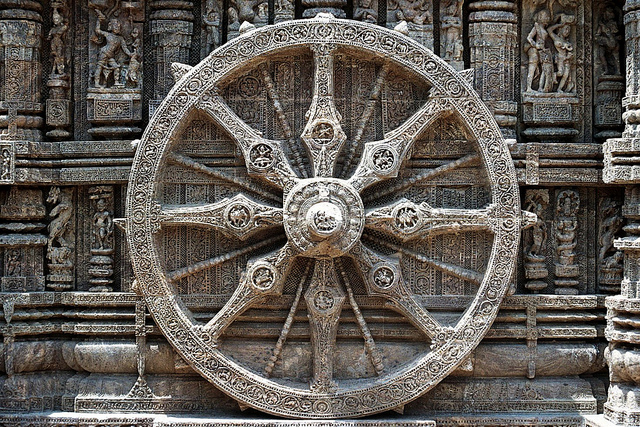

Image credit – saamiblog

A Healthy Dose of Heresy

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

Anything worth its salt will meet with resistance. More strongly, if you get no resistance, don’t bother.

There’s huge momentum around doing what worked last time. Same as last time but better; build on success; leverage last year’s investment; we know how to do it. Why are these arguments so appealing? Two words: comfort and perceived risk. Why these arguments shouldn’t be so appealing: complacency and opportunity cost.

We think statically and selectively. We look in the rear view mirror, write down what happened and say “let’s do that again.” Hey, why not? We made the initial investment and did the leg work. We created the script. Let’s get some mileage out of it. And we selectively remember the positive elements and actively forget the uncertainty of the moment. We had no idea it was going to work, and we forget that part. It worked better than we imagined and we remember the “working better” part. And we forget we imagined it would go differently. And we forget that was a long time ago and we don’t take the time to realize things are different now. The rules are dynamic, yet our thinking is static.

We compete with the past tense. We did this and they did that, and, therefore, that’s what will happen again. So wrong. We’ve got smarter; they’ve got smarter; battery capacity has tripled; power electronics are twice as efficient; efficiency of solar panels has doubled; CRISPR can edit our genes. The rules are different but the sheet music hasn’t changed. The established players sing the same songs and the upstarts cut them off at the knees.

If you were successful last time and everyone thinks your proposed project is a good idea, ball it up and throw it in the trash. It reeks of stale thinking. If your project plan is dismissed by the experts because it contradicts the tired recipe of success, congratulations! You may be onto something! Stomp on the accelerator and don’t look back.

If your proposal meets with consensus, hang your head and try again. You missed the mark. If they scream “heretic” and want to burn you at the stake, double down. If the CEO isn’t adamantly against it, you’re not trying hard enough. If she throws you out of the room half way through your presentation, you may have a winner!

Yesterday’s recipes for success are today’s worn paths of mediocracy.

If you’re confident it will work, you shouldn’t be. If you’re filled with electric excitement it might actually work and scared to death it might end in a wild fireball of burn metal toxic fumes, what are you waiting for?!

Heretics were burned at the stake because the establishment knew they were right. Goddard was right and the New York Times wasn’t. Decades later they apologized – rockets work is space. And though the Qualifiers and Pope Paul V were unanimous in their dismissal of Galileo and Copernicus, the heretics had it right – the sun is at the center of everything.

Don’t seek out dissent, but if all you get is consensus, be wary. Don’t be adversarial, but if all you get is open arms, question your thesis. Don’t be confrontational, but if all you get is acceptance, something’s wrong.

If there’s no resistance, work on something else.

Image Credit WPI (Robert Goddard’s Lab)

The Leader’s Journey

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you’re pretty sure what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you think you may know what to do, do it. Don’t ask, just do.

If you don’t know what to do, try something small. Then, do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

If your team doesn’t know what to do unless they ask you, tell them to do what they think is right. And tell them to stop asking you what to do.

If your team won’t act without your consent, tell them to do what they think is right. Then, next time they seek your consent, be unavailable.

If the team knows what to do and they go around you because they know you don’t, praise them for going around you. Then, set up a session where they educate you on what you should know.

If the team knows what to do and they know you don’t, but they don’t go around you because they are too afraid, apologize to them for creating a fear-based culture and ask them to do what they think is right. Then, look inside to figure out how to let go of your insecurities and control issues.

If your team needs your support, support them.

If your team need you to get out of the way, go home early.

If your team needs you to break trail, break it.

If they need to see how it should go, show them.

If they need the rules broken, break them.

If they need the rules followed, follow them.

If they need to use their judgement, create the causes and conditions for them to use their judgement.

If they try something new and it doesn’t go as anticipated, praise them for trying something new.

If they try the same thing a second time and they get the same results and those results are still unanticipated, set up a meeting to figure out why they thought the same experiment would lead to different results.

Try to create the team that excels when you go on vacation.

Better yet, try to create the team that performs extremely well when you’re involved in the work and performs even better when you’re on vacation. Then, because you know you’ve prepared them for the future, happily move on to your next personal development opportunity.

Image credit — Puriri deVry

It’s time to stretch yourself.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

To find the right balance point, start with an assessment of your stretch level. List the number of projects you have and sum the number of major deliverables you’ve got to deliver. If you have more than three projects, you have too many. And if you think you take on more than three because you’re superhuman, you’re wrong. The data is clear – multitasking is a fallacy. If you have four projects you have too many. And it’s the same with three, but you’d think I was crazy if I suggested you limit your projects to two. The right balance point starts with reducing the number of projects you work on.

Now that you eliminated four or five projects and narrowed the portfolio down to the vital two or three, it’s time to list your major deliverables. Take a piece of paper and write them in a column down the left side of the page. And in a column next to the projects, categorize each of them as: -1 (done it before), 0 (done something similar), 1 (new to me), 2 (new to team), 3 (new to company), 5 (new to industry), 11 (new to world).

For the -1s, teach an entry level person how to do it and make sure they do it well. For the 0s, find someone who deserves a growth opportunity and let them have the work. And check in with them to make sure they do a good job. The idea is to free yourself for the stretch work.

For the 1s, find the best person in the team who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, do as they suggest but build on their work and take it to the next level.

For the 2s, find the best person in the company who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, build on their approach and make it your own.

For the 3s, do your research and find out who in your industry has done it before. Figure out how they did it and improve on their work.

For the 5s, do your research and figure out who has done similar work in another industry. Adapt their work to your application and twist it into something magical.

And for the 11s, they’re a special project category that live in rarified air and deserve a separate blog post of their own.

Start with where you are – evaluate your existing deliverables, cull them to a reasonable workload and assess your level of stretch. And, where it makes sense, stop doing work you’ve done before and start doing work you haven’t done yet. Stretch yourself, but be reasonable. It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Image credit – filtran

The Evolution of New Ideas

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

Before there is something new to see, there is just a good idea worthy of a prototype. And before there can be good ideas there are a whole flock of bad ones. And until you have enough self confidence to have bad ideas, there is only the status quo. Creating something from nothing is difficult.

New things are new because they are different than the status quo. And if the status quo is one thing, it’s ruthless in desire to squelch the competition. In that way, new ideas will get trampled simply based on their newness. But also in that way, if your idea gets trampled it’s because the status quo noticed it and was threatened by it. Don’t look at the trampling as a bad sign, look at it as a sign you are on the right track. With new ideas there’s no such thing as bad publicity.

The eureka moment is a lie. New ideas reveal themselves slowly, even to the person with the idea. They start as an old problem or, better yet, as a successful yet tired solution. The new idea takes its first form when frustration overcomes intellectual inertia a strange sketch emerges on the whiteboard. It’s not yet a good idea, rather it’s something that doesn’t make sense or doesn’t quite fit.

The idea can mull around as a precursor for quite a while. Sometimes the idea makes an evolutionary jump in a direction that’s not quite right only to slither back to it’s unfertilized state. But as the environment changes around it, the idea jumps on the back of the new context with the hope of evolving itself into something intriguing. Sometimes it jumps the divide and sometimes it slithers back to a lower energy state. All this happens without conscious knowledge of the inventor.

It’s only after several mutations does the idea find enough strength to make its way into a prototype. And now as a prototype, repeats the whole process of seeking out evolutionary paths with the hope of evolving into a product or service that provides customer value. And again, it climbs and scratches up the evolutionary ladder to its most viable embodiment.

Creating something new from scratch is difficult. But, you are not alone. New ideas have a life force of their own and they want to come into being. Believe in yourself and believe in your ideas. Not every idea will be successful, but the only way to guarantee failure is to block yourself from nurturing ideas that threaten the status quo.

Image credit – lost places

Starting 101

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

The downside of making a mistake is far less than the downside of not starting.

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long to start.

Stopping is fine, as long as it’s followed closely by starting.

The scope of the project you start is defined by the cash in your pocket.

If you don’t start you can’t learn.

The project doesn’t have to be all figured out before starting, you just have to start.

Starting is scary because it’s important.

Before you can start you’ve got to decide to start.

If you’re finally ready to start, you should have started yesterday.

Without starting there can be no finishing.

Starting is blocked by both the fear of success and the fear of failure.

You don’t need to be ready to start, you just need to start.

The only thing in the way of starting is you.

Image credit — Dermot O’Halloran

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

Complaining isn’t a strategy.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

It’s easy to complain about how things are going, especially when they’re not going well. But even with the best intentions, complaining doesn’t move the organization in a new direction. Sometimes people complain to attract attention to an important issue. Sometimes it’s out of frustration, sometimes out of sadness and sometimes out of fear, but it’s never the best mechanism.

If the intention is to convey importance, why not convey the importance by explaining why it’s important? Why not strip the issue of its charge and use an approach and language that help people understand why it’s important? It’s a simple shift from complaining to explaining, but it can make all the difference. Where complaining distracts, explaining brings people together. And if it’s truly important, why not take the time to have a give-and-take conversation and listen to what others have to say? Instead of listening to respond, why not listen to understand?

If you’re not willing to understand someone else’s position it’s not a conversation.

And if you’re on the receiving end of a complaint, how can you learn to see it as a sign of importance and not as an attack? As the receiver, why not strip it of its charge and ask questions of clarification? Why not deescalate and move things from complaint to conversation? Understanding is not agreeing, but it still a step forward for everyone.

When two sides are divided, complaining doesn’t help, even if it’s well-intentioned. When two sides are divided and there’s strong emotion, the first step is to take responsibility to deescalate. And once emotions are calmed, the next step is to take responsibility to understand the other side. At this stage, there is no requirement to agree, but there can be no hint of disagreement as it will elevate emotions and set progress back to zero. It’s a slow process, but when the issues are highly charged, it’s the fastest way to come together.

If you’re dissatisfied with the negativity, demonstrate positivity. If you want to come together, take the first step toward the middle. If you want to generate the trust needed to move things forward, take action that builds trust.

If you want things to be different, look inside.

Image credit – Ireen2005

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski