Posts Tagged ‘Fear’

How To See What’s Missing

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

And the same can be said for an organization. When everyone sees things from a single perspective, the organization has no depth perception. But with at least two perspectives, the organization can better see things as they are. The problem is we’re not taught to see from unique perspectives.

With most presentations, the material is delivered from a single perspective with the intention of helping everyone see from that singular perspective. Because there’s no depth to the presentation, it looks the same whether you look at it with one eye or two. But with some training, you can learn how to see depth even when it has purposely been scraped away.

And it’s the same with reports, proposals, and plans. They are usually written from a single perspective with the objective of helping everyone reach a single conclusion. But with some practice, you can learn to see what’s missing to better see things as they are.

When you see what’s missing, you see things in stereo vision.

Here are some tips to help you see what’s missing. Try them out next time you watch a presentation or read a report, proposal, or plan.

When you see a WHAT, look for the missing WHY on the top and HOW on the bottom. Often, at least one slice of bread is missing from the why-what-how sandwich.

When you see a HOW, look for the missing WHO and WHEN. Usually, the bread or meat is missing from the how-who-when sandwich.

Here’s a rule to live by: Without finishing there can be no starting.

When you see a long list of new projects, tasks, or initiatives that will start next year, look for the missing list of activities that would have to stop in order for the new ones to start.

When you see lots of starting, you’ll see a lot of missing finishing.

When you see a proposal to demonstrate something for the first time or an initial pilot, look for the missing resources for the “then what” work. After the prototype is successful, then what? After the pilot is successful, then what? Look for the missing “then what” resources needed to scale the work. It won’t be there.

When you see a plan that requires new capabilities, look for the missing training plan that must be completed before the new work can be done well. And look for the missing budget that won’t be used to pay for the training plan that won’t happen.

When you see an increased output from a system, look for the missing investment needed to make it happen, the missing lead time to get approval for the missing investment, and the missing lead time to put things in place in time to achieve the increased output that won’t be realized.

When you see a completion date, look for the missing breakdown of the work content that wasn’t used to arbitrarily set the completion date that won’t be met.

When you see a cost reduction goal, look for the missing resources that won’t be freed up from other projects to do the cost reduction work that won’t get done.

It’s difficult to see what’s missing. I hope you find these tips helpful.

“missing pieces” by LeaESQUE is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Regardless of the problem, the solution lives inside you.

If you want things to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want things to stay the same, you also have a problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain, you can do something about it, or you can accept things as they are.

If you want things to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want things to stay the same, you also have a problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain, you can do something about it, or you can accept things as they are.

Complaining can be fun for a while, then it turns sour. Doing something about it can take a lot of time and energy, and it’s difficult to know what to do. Accepting things as they are can be a challenge because that means it’s time to change your perspective. But it’s your choice. So, what do you choose?

What does it look like to accept things as they are AND do something about it?

If you want someone to be different than they are, you have a problem. And if you want them to stay the same, you have a different problem. Either way, you have a problem. You can complain about them, you can do something about it, or you can accept them as they are.

Complaining about people can be fun, but only in small doses. Doing something about it, well, that’s difficult because people will do what they want to do, not what you want them to do. Accepting people as they are is difficult because it means you have to look inside and change yourself. But it’s your choice. So, what do you choose?

What does it look like to accept people as they are AND to do something that makes things better for all?

If you have a problem with things changing, the solution lives inside you. Things change. That’s what they do. And if you have a problem with things staying the same, the solution lives inside you. Things stay the same. That’s what they do. Either way, the solution lives inside you, and it’s time to look inside.

How would it feel to own your problem and look inside for the solution?

If you have a problem because you want people to be different, the solution lives inside you. People behave the way they want to behave, not the way you want them to behave. And if you have a problem because you want people to stay the same, the solution lives inside you. People change. That’s what they do. Either way, the problem is you, and it’s time to look inside for the solution.

How would it feel to accept people as they are and look inside to solve your problem?

Certainty or novelty – it’s your choice.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

When you follow the best practice, by definition your work is not new. New work is never done the same way twice. That’s why it’s called new.

Best practices are for old work. Usually, it’s work that was successful last time. But just as you can never step into the same stream twice, when you repeat a successful recipe it’s not the same recipe. Almost everything is different from last time. The economy is different, the competitors are different, the customers are in a different phase of their lives, the political climate is different, interest rates are different, laws are different, tariffs are different, the technology is different, and the people doing the work are different. Just because work was successful last time doesn’t mean that the old work done in a new context will be successful next time. The most important property of old work is the certainty that it will run out of gas.

When someone asks you to follow the best practice, they prioritize certainty over novelty. And because the context is different, that certainty is misplaced.

We have a funny relationship with certainty. At every turn, we try to increase certainty by doing what we did last time. But the only thing certain with that strategy is that it will run out of gas. Yet, frantically waving the flag of certainty, we continue to double down on what we did last time. When we demand certainty, we demand old work. As a company, you can have too much “certainty.”

When you flog the teams because they have too much uncertainty, you flog out all the novelty.

What if you start the design review with the question “What’s novel about this project?” And when the team says there’s nothing novel, what if you say “Well, go back to the drawing board and come back with some novelty.”? If you seek out novelty instead of squelching it, you’ll get more novelty. That’s a rule, though not limited to novelty.

A bias toward best practices is a bias toward old work. And the belief underpinning those biases is the belief that the Universe is static. And the one thing the Universe doesn’t like to be called is static. The Universe prides itself on its dynamic character and unpredictable nature. And the Universe isn’t above using karma to punish those who call it names.

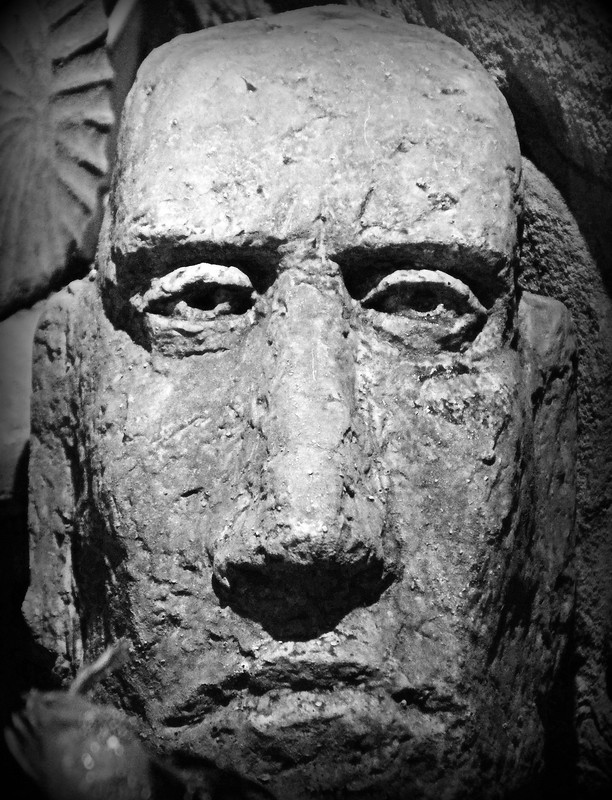

“Stonecold certainty” by philwirks is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The Illusion of Control

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Happy: When you accept things as they are.

Sad: When you fixate on times when things turned out differently than you wanted.

Neutral: When you know you have little control over how things will turn out.

Anxious: When you fixate on times when things might turn out differently than you want.

Stressed: When you think you have control over how things will turn out.

Relaxed: When you know you don’t have control over how things will turn out.

Agitated: When you live in the future.

Calm: When you live in the present.

Sad: When you live in the past.

Angry: When you expect a just world, but it isn’t.

Neutral: When you expect that it could be a just world, but likely isn’t.

Happy: When you know it doesn’t matter if the world is just.

Angry: When others don’t meet your expectations.

Neutral: When you know your expectations are about you.

Happy: When you have no expectations.

Timid: When you think people will judge you negatively.

Neutral: When you think people may judge you negatively or positively.

Happy: When you know what people think about you is none of your business.

Distracted: When you live in the past or future.

Focused: When you live in the now.

Afraid of change: When you think all things are static.

Accepting change: When you know all things are dynamic.

Intimidated: When you think you don’t meet someone’s expectations.

Confident: When you know you did your best.

Uncomfortable: When you want things to be different than they are.

Comfortable: When you know the Universe doesn’t care what you think.

“Space – Antennae Galaxies” by Trodel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

What will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When you’re dead and gone, what stories will your kids tell about you?

What stories will your coworkers tell?

How about your bosses?

Will they see your disagreement as mischievous or skillful?

Will they see your frustration as disruptive or caring?

Will they see your vehemence as disrespectful or passionate?

Will they see your divergent views as contrarian or well-intentioned?

Will they see your withholding as passive-aggressive or as the result of exhausting all other possibilities?

Will they see your tears as sadness for yourself or the company you care about deeply?

Will they see your “no’s” as curmudgeonly given or brave?

Will they see your dissent as destructive or constructive?

Will they see your frustration as immaturity or as others falling short of your high expectations?

Will they see your unpopular perspective as troublemaking or as the antidote to groupthink?

Will they see your positivity as fake or as the support that everyone needs to do their best work?

Here’s the thing: What matters is not what it looks like from the outside, but your intentions.

And another thing: Anyone that knows you knows your intentions.

Now, go out and do what you think is right. And do it like you mean it. And don’t look back.

And here’s a mantra: What people think about you is none of your business.

Will you be remembered?

100% agreement means there’s less than 100% truth. If, as a senior leader, you know there are differing opinions left unsaid, what would you do? Would you chastise the untruthful who are afraid to speak their minds? Would you simply ignore what you know to be true and play Angry Birds on your phone? Would you make it safe for the fearful to share their truth? Or would you take it on the chin and speak their truth? As a senior leader, I’d do the last one.

100% agreement means there’s less than 100% truth. If, as a senior leader, you know there are differing opinions left unsaid, what would you do? Would you chastise the untruthful who are afraid to speak their minds? Would you simply ignore what you know to be true and play Angry Birds on your phone? Would you make it safe for the fearful to share their truth? Or would you take it on the chin and speak their truth? As a senior leader, I’d do the last one.

Best practice is sometimes a worst practice. If, as a senior leader, you know a more senior leader is putting immense pressure put on the team to follow a best practice, yet the context requires a new practice, what would you do? Would you go along with the ruse and support the worst practice? Would you keep your mouth shut and play tick-tack-toe until the meeting is over? Would you suggest a new practice, help the team implement it, and take the heat from the Status Quo Police? As a senior leader, I’d do the last one.

Truth builds trust. If, as a senior leader, you know the justification for a new project has been doctored, what would you do? Would you go along with the charade because it’s easy? Would call out the duplicity and preserve the trust you’ve earned from the team over the last decade? As a senior leader, I’d do the last one.

The loudest voice isn’t the rightest voice. If, as a senior leader, you know a more senior leader is using their positional power to strong-arm the team into a decision that is not supported by the data, what would you do? Would you go along with it, even though you know it’s wrong? Would you ask a probing question that makes it clear there is some serious steamrolling going on? And if that doesn’t work, would you be more direct and call out the steamrolling for what it is? As a senior leader, I’d do the last two.

What’s best for the company is not always best for your career. When you speak truth to power in the name of doing what’s best for the company, your career may suffer. When you see duplicity and call it by name, the company will be better for it, but your career may not. When you protect people from the steam roller, the team will thank you, but it may cost you a promotion. When you tell the truth, the right work happens and you earn the trust and respect of most everyone. As a senior leader, if your career suffers, so be it.

When you do the right thing, people remember. When, in a trying time, you have someone’s back, they remember. When a team is unduly pressured and you put yourself between them and the pressure, they remember. When you step in front of the steamroller, people remember. And when you silence the loudest voice so the right decision is made, people remember. As a senior leader, I want to be remembered.

Do you want to be remembered as someone who played Angry Birds or advocated for those too afraid to speak their truth?

Do you want to be remembered as someone who doodled on their notepad or spoke truth to power?

Do you want to be remembered as someone who kept their mouth shut or called out the inconvenient truth?

Do you want to be remembered as someone who did all they could to advance their career or someone who earned the trust and respect of those they worked with?

In the four cases above, I choose the latter.

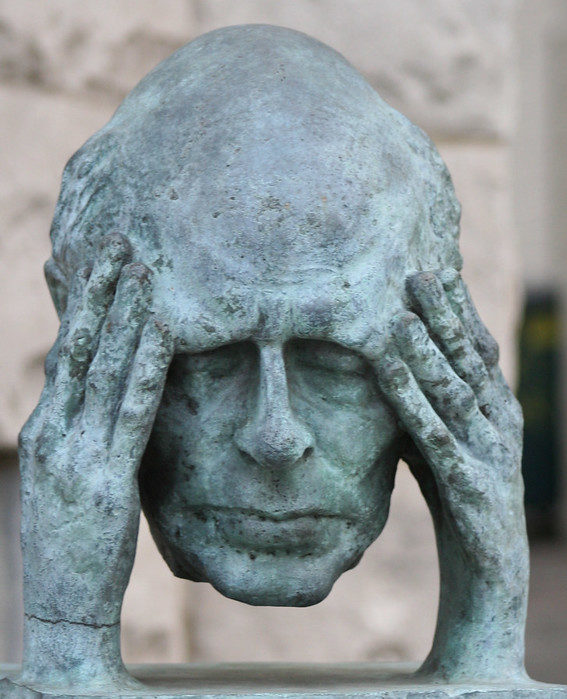

“cryptic.” by dfactory is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When is it innovation theater?

When you go to the cinema or the playhouse you go you see a show. The show may be funny, it may be sad, it may be thought-provoking, it may be beautiful, and it may take your mind off your problems for a couple of hours; but it’s not real. Sure, the storyline is good, but it came from someone’s imagination. And because it’s a story, it doesn’t have to bound by reality. Sure, the choreography is catchy, but it’s designed for effect. Yes, the cinematography paints a good picture, but it’s contrived. And, yes, the actors are good, but they’re actors. What you see isn’t real. What you see is theater.

When you go to the cinema or the playhouse you go you see a show. The show may be funny, it may be sad, it may be thought-provoking, it may be beautiful, and it may take your mind off your problems for a couple of hours; but it’s not real. Sure, the storyline is good, but it came from someone’s imagination. And because it’s a story, it doesn’t have to bound by reality. Sure, the choreography is catchy, but it’s designed for effect. Yes, the cinematography paints a good picture, but it’s contrived. And, yes, the actors are good, but they’re actors. What you see isn’t real. What you see is theater.

If you are asked to focus on the innovation process, that’s theater. Innovation doesn’t care about process; it cares about delivering novel customer value. The process isn’t most important, the output is. When there’s an extreme focus on the process that usually means an extreme focus on the output of the process would be embarrassing.

If you are tasked to calculate the net present value of the project hopper, that’s theater. With innovation, there’s no partial credit for projects you’re not working on. None. The value of the projects in the hopper is zero. The song about the value of the project hopper is nothing more than a catchy melody performed to make sure the audience doesn’t ask about the feeble collection of projects you are working on. And, assigning a value to the stagnant project hopper is a creative storyline crafted to hide the fact you have too many projects you’re not working on.

If you are asked to create high-level metrics and fancy pie charts, that’s innovation theater. Process metrics and pie charts don’t pay the bills. Here’s innovation’s script for paying the bills: complete amazing projects, launch amazing products, and sell a boatload. Full stop. If your innovation script is different than that, ball it up and throw it away along with its producer.

If the lame projects aren’t stopped so better ones can start, if people aren’t moved off stale projects onto amazing ones, if the same old teams are charged with the innovation mandate, if new leaders aren’t added, if the teams are measured just like last year, that’s innovation theater. How many mundane projects have you stopped? How many amazing projects have you started? How many new leaders have you added? How many new teams have you formed? How will you measure your teams differently? How do you feel about all that?

If a return on investment (ROI) calculation is the gating criterion before starting an amazing project, that’s innovation theater. Projects that could create a new product family with a fundamentally different value proposition for a whole new customer segment cannot be assigned an ROI because no one has experience in this new domain. Any ROI will be a guess and that’s why innovation is governed by judgment and not ROI. Innovation is unpredictable which makes an ROI is impossible to predict. And if your innovation process squeezes judgment out of the storyline, that’s a tell-tale sign of innovation theater.

If the specifications are fixed, the resources are fixed, and the completion date is fixed, that’s innovation theater. Since it can be innovation only when there’s novelty, and since novelty comes with uncertainty, without flexibility in specs, resources, or time, it’s innovation theater.

If the work doesn’t require trust, it’s innovation theater. If trust is not required it’s because the work has been done before, and if that’s the case, it’s not innovation.

If you know it will work, it’s innovation theater. Innovation and certainty cannot coexist.

If a steering team is involved, it’s innovation theater. Consensus cannot spawn innovation.

If more than one person in charge, it’s innovation theater. With innovation, there’s no place for compromise.

And what to do when you realize you’re playing a part in your company’s innovation theater? Well, I’ll save that for another time.

“Large clay theatrical mask, Romisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne” by Following Hadrian is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Do you have a problem?

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If you fix someone else’s problem, you prevent the organization from fixing the root cause.

If you see a problem, say something.

If you see a problem, you have an obligation to do something, but not an obligation to fix it.

If someone tries to give you their stinky problem and you don’t accept it, it’s still theirs.

If you think the problem is a symptom of a bigger problem, fixing the small problem doesn’t fix anything.

If someone isn’t solving their problem, maybe they don’t know they have a problem.

If someone you care about has a problem, help them.

If someone you don’t care about has a problem, help them, too.

If you don’t have a problem, there can be no progress.

If you make progress, you likely solved a problem.

If you create the right problem the right way, you presuppose the right solution.

If you create the right problem in the right way, the right people will have to solve it.

If you want to create a compelling solution, shine a light on a compelling problem.

If there’s a big problem but no one wants to admit it, do the work that makes it look like the car crash it is.

If you shine a light on a big problem, the owner of the problem won’t like it.

If you shine a light on a big problem, make sure you’re in a position to help the problem owner.

If you’re not willing to contribute to solving the problem, you have no right to shine a light on it.

If you can’t solve the problem, it’s because you’ve defined it poorly.

Problem definition is problem-solving.

If you don’t have a problem, there’s no problem.

And if there’s no problem, there can be no solution. And that’s a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, how can you have a solution?

If you want to create the right problem, create one that tugs on the ego.

If you want to shine a light on an ego-threatening problem, make it as compelling as a car crash – skid marks and all.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, give them an opportunity to own it, and then turn on the lights.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, so be it.

If it’s not your problem, keep your hands in your pockets or it will become your problem.

But no one can give you their problem without your consent.

If you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, the problem at hand isn’t your biggest problem.

If you see a problem but it’s not yours to fix, you’re not obliged to fix it, but you are obliged to shine a light on it.

When it comes to problems, when you see something, say something.

But, if shining a light on a big problem is a problem, well, you have a bigger problem.

“No Problem!” by Andy Morffew is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Technical Risk, Market Risk, and Emotional Risk

Technical risk – Will it work?

Market risk – Will they buy it?

Emotional risk – Will people laugh at your crazy idea?

Technical risk – Test it in the lab.

Market risk – Test it with the customer.

Emotional risk – Try it with a friend.

Technical risk – Define the right test.

Market risk – Define the right customer.

Emotional risk – Define the right friend.

Technical risk – Define the minimum acceptable performance criteria.

Market risk – Define the minimum acceptable response from the customer.

Emotional risk – Define the minimum acceptable criticism from your friend.

Technical risk – Can you manufacture it?

Market risk – Can you sell it?

Emotional risk – Can you act on your crazy idea?

Technical risk – How sure are you that you can manufacture it?

Market risk – How sure are you that you can sell it?

Emotional risk – How sure are you that you can act on your crazy idea?

Technical risk – When the VP says it can’t be manufactured, what do you do?

Market risk – When the VP says it can’t be sold, what do you do?

Emotional risk – When the VP says your idea is too crazy, what do you do?

Technical risk – When you knew the technical risk was too high, what did you do?

Market risk – When you knew the market risk was too high, what did you do?

Emotional risk – When you knew someone’s emotional risk was going to be too high, what did you do?

Technical risk – Can you teach others to reduce technical risk? How about increasing it?

Market risk – Can you teach others to reduce technical risk? How about increasing it?

Emotional risk – Can you teach others to reduce emotional risk? How about increasing it?

Technical risk – What does it look like when technical risk is too low? And the consequences?

Market risk – What does it look like when technical risk is too low? And the consequences?

Emotional risk – What does it look like when emotional risk is too low? And the consequences?

We are most aware of technical risk and spend most of our time trying to reduce it. We have the mindset and toolset to reduce it. We know how to do it. But we were not taught to recognize when technical risk is too low. And if we do recognize it’s too low, we don’t know how to articulate the negative consequences. With all this said, market risk is far more dangerous.

We’re unfamiliar with the toolset and mindset to reduce market risk. Where we can change the design, run the test, and reduce technical risk, market risk is not like that. It’s difficult to understand what drives the customers’ buying decision and it’s difficult to directly (and quickly) change their buying decision. In short, it’s difficult to know what to change so they make a different buying decision. And if they don’t buy, you don’t sell. And that’s a big problem. With that said, emotional risk is far more debilitating.

When a culture creates high emotional risk, people keep their best ideas to themselves. They don’t want to be laughed at or ridiculed, so their best ideas don’t see the light of day. The result is a collection of wonderful ideas known only to the underground Trust Network. A culture that creates high emotional risk has insufficient technical and market risk because everyone is afraid of the consequences of doing something new and different. The result – the company with high emotional risk follows the same old script and does what it did last time. And this works well, right up until it doesn’t.

Here’s a three-pronged approach that may help.

- Continue to reduce technical risk.

- Learn to reduce market risk early in a project.

- And behave in a way that reduces emotional risk so you’ll have the opportunity to reduce technical and market risk.

Image credit — Shan Sheehan

Feel It All

In these trying times, when 30% of Americans cannot pay their rent or mortgage, is it okay to put hard limits on the amount of work we do or to take good care of ourselves or to feel good about taking a vacation?

In these trying times, when 30% of Americans cannot pay their rent or mortgage, is it okay to put hard limits on the amount of work we do or to take good care of ourselves or to feel good about taking a vacation?

With remote work, we commute less, which should give us more time to take care of ourselves. But, do you have more time? If you do, what do you do with your freed-up time? Do you work more? Do you exercise? Do you worry? Do you take the time to feel grateful that you have a job?

When you work from home do you stop and make time to eat lunch? Do you shut off the work and just eat? Or, do you eat while you work? Do you take more time than when you are (or were) in the office or less? If you take more time to eat than when at the office, do you feel good that you’re taking care of yourself? Or, if you take less, do you feel good you’re doing all you can to prevent layoffs? Or, are you simply thankful you still have healthcare benefits?

When you work at home do you attend too many Zoom meetings? If so, what happens to all the work you can’t get done? Do you attend half-heartedly and multitask (work on something else)? Multitasking is disrespectful to the Zoom meeting and the other work, but do you have a choice? To get the work done, do you extend your workday to include your non-commute time? Or, do you decline Zoom meetings because other work is more important? Is it okay to decline a Zoom meeting?

Do you feel good when you set limits to preserve your emotional well-being? Do you preserve your well-being or do you do all you can to keep your job?

And now the tough one. Do you feel good when you go on vacation or do you feel sad because so many citizens have lost their jobs?

Thing is, it’s not or. It’s and.

It’s not that we must feel bad when we work during our non-commute time or feel good when we take care of ourselves or feel thankful for our jobs or feel bad because so many have lost theirs. It’s not or, it’s and. We’ve got to hold all these feelings at once. Tough to do, but we can.

It’s not that we feel bad when we work through lunch or feel good when we go for a walk or feel happy when we do all we can to prevent layoffs or we are thankful we have a job at all. It’s and. We’ve got to handle it all at once. We do what we can to prevent layoffs and take care of ourselves. We feel it all and make the choice.

We attend Zoom meetings and decline them and multitask. We process the three potential realities and choose. The bad ones we decline, the good ones we attend wholeheartedly, and for the others we multitask.

We feel great when we go on vacation and feel sad that others are in a bad way. We feel both at the same time.

Or, as word, is binary, black and white. But today’s realities are not black and white and there is no best way.

If you’re looking for some relief during these trying times, give “and” a try. Feel happy and sad. Feel grateful and scared. Feel it all and see what happens.

I hope it brings you peace.

Image credit — David

Wrong Questions to Ask When Doing Technology Development

I know you’re trying to do something that has never been done before, but when will you be done? I don’t know. We’ll run the next experiment then decide what to do next. If it works, we’ll do more of that. And if it doesn’t, we’ll do less of that. That’s all we know right now.

I know you’re trying to do something that has never been done before, but when will you be done? I don’t know. We’ll run the next experiment then decide what to do next. If it works, we’ll do more of that. And if it doesn’t, we’ll do less of that. That’s all we know right now.

I know you’re trying to create something that is new to our industry, but how many will we sell? I don’t know. Initial interviews with customers made it clear that this is an important customer problem. So, we’re trying to figure out if the technology can provide a viable solution. That’s all we know right now.

No one is asking for that obscure technology. Why are you wasting time working on that? Well, the voice of the technology and the S-curve analyses suggest the technology wants to move in this direction, so we’re investing this solution space. It might work and it might not. That’s all we know right now.

Why aren’t you using best practices? If it hasn’t been done before, there can be no best practice. We prefer to use good practice or emergent practice.

There doesn’t seem like there’s been much progress. Why aren’t you running more experiments? We don’t know which experiments to run, so we’re taking some time to think about what to do next.

Will it work? I don’t know.

That new technology may obsolete our most profitable product line. Shouldn’t you stop work on that? No. If we don’t obsolete our best work, someone else will. Wouldn’t it be better if we did the obsoleting?

How many more people do you need to accelerate the technology development work? None. Small teams are better.

Sure, it’s a cool technology, but how much will it cost? We haven’t earned the right to think about the cost. We’re still trying to make it work.

So, what’s your solution? We don’t know yet. We’re still trying to formulate the customer problem.

You said you’d be done two months ago. Why aren’t you done yet? I never said we’d be done two months ago. You asked me for a completion date and I could not tell you when we’d be done. You didn’t like that answer so I suggested that you choose your favorite date and put that into your spreadsheet. We were never going to hit that date, and we didn’t.

We’ve got a tight timeline. Why are you going home at 5:00? We’ve been working on this technology for the last two years. This is a marathon. We’re mentally exhausted. See you tomorrow.

If you don’t work harder, we’ll get someone else to do the technology development work. What do you think about that? You are confusing activity with progress. We are doing the right analyses and the right thinking and we’re working hard. But if you’d rather have someone else lead this work, so would I.

We need a patented solution. Will your solution be patentable? I don’t know because we don’t yet have a solution. And when we do have a solution, we still won’t know because it takes a year or three for the Patent Office to make that decision.

So, you’re telling me this might not work? Yes. That’s what I’m telling you.

So, you don’t know when you’ll be done with the technology work, you don’t know how much the technology will cost, you don’t know if it will be patentable, or who will buy it? That’s about right.

Image credit — Virtual EyeSee

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski