Posts Tagged ‘Fear’

The Ins and Outs of Things

When things are overwhelming to you but not to others, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed for a while.

When things are overwhelming to you but not to others, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed for a while.

When the seas are rough, you may think you are alone, but others may see it differently.

What’s worthy of your attention is defined by you, though some make it easy for you to think otherwise.

When you disagree with someone’s idea, that says nothing about them.

Judging someone from the outside is unfair, and it’s the same with judging yourself from the inside.

When everyone around you sees you differently than you see yourself, it’s worth looking critically at what you see that they don’t and what they see that you don’t.

You aren’t your thoughts and feelings, but it can feel like it in the heat of the moment.

Self-judgment is the strongest flavor of judgment.

“Object from the exhibition We call them Vikings produced by The Swedish History Museum” by The Swedish History Museum, Stockholm is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The Power of Stopping

If when you write your monthly report no one responds with a question of clarification or constructive comment, this may be a sign your organization places little value on your report and the work it stands for. If someone sends a thank you email and do not mention something specific in your report, this masked disinterest is a half-step above non-interest and is likely also a sign your organization places little value on your report and the work it stands for.

If when you write your monthly report no one responds with a question of clarification or constructive comment, this may be a sign your organization places little value on your report and the work it stands for. If someone sends a thank you email and do not mention something specific in your report, this masked disinterest is a half-step above non-interest and is likely also a sign your organization places little value on your report and the work it stands for.

If you want to know for sure what people think of your work, stop writing your report. If no one complains, your work is not valuable to the company. If one person complains, it’s likely still not valuable. And if that single complaint comes from your boss, your report/work is likely not broadly valuable, but you’ll have to keep writing the report.

But don’t blame the organization because they don’t value your work. Instead, ask yourself how your work must change so it’s broadly valuable. And if you can’t figure a way to make your work valuable, stop the work so you can start work that is.

If when you receive someone else’s monthly report and you don’t reply with a question of clarification or constructive comment, it’s because you don’t think their work is all that important. And if this is the case, tell them you want to stop receiving their report and ask them to stop sending them to you. Hopefully, this will start a discussion about why you want to stop hearing about their work which, hopefully, will lead to a discussion about how their work could be modified to make it more interesting and important. This dialog will go one of two ways – they will get angry and take you off the distribution list or they will think about your feedback and try to make their work more interesting and important. In the first case, you’ll receive one fewer report and in the other, there’s a chance their work will blossom into something magical. Either way, it’s a win.

While reports aren’t the work, they do stand for the work. And while reports are sometimes considered overhead, they do perform an inform function – to inform the company of the work that’s being worked. If the work is amazing, the reports will be amazing and you’ll get feedback that’s amazing. And if the work is spectacular, the reports will be spectacular and you’ll get feedback that matches.

But this post isn’t about work or reports, it’s about the power of stopping. When something stops, the stopping is undeniable and it forces a discussion about why the stopping started. With stopping, there can be no illusion that progress is being made because stopping is binary – it’s either stopped or it isn’t. And when everyone knows progress is stopped, everyone also knows the situation is about to get some much-needed attention from above, wanted or not.

Stopping makes a statement. Stopping gets attention. Stopping is serious business.

And here’s a little-known fact: Starting starts with stopping.

Image credit — joiseyshowaa

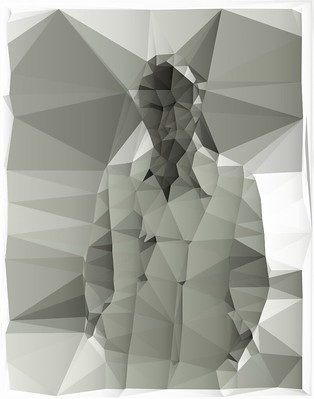

Triangulation of Leadership

Put together things that contradict yet make a wonderfully mismatched pair.

Say things that contradict common misunderstandings.

See the dark and dirty underside of things.

Be more patient with people.

Stomp on success.

Dissent.

Tell the truth even when it’s bad for your career.

See what wasn’t but should have been.

Violate first principles.

Protect people.

Trust.

See things as they aren’t.

See what’s missing.

See yourself.

See.

“man in park (triangulation)” by Josh (broma) is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Do you build trust or break it?

When someone tells you their truth, what do you do? Do you ask them to defend? Do you tell them what you think? Do you dismiss them? Do you listen? Do you believe them?

When someone has the courage to tell you their truth, they demonstrate they trust you. If you want to destroy their trust, ask them to defend their truth. Sooner or later, or then and there, they’ll stop trusting you. And like falling off a cliff, it’s almost impossible for things to be the same.

When someone confesses their truth, they demonstrate they trust you enough to share a difficult issue with you. If you want them to feel small and block them from sharing their truth in the future, tell them why their truth isn’t right. That will be the last time they speak candidly with you. Ever.

When someone reluctantly shares their truth, they demonstrate they’re willing to push through their discomfort due to the significance and their trust in you. If you want them to get angry, explain how they see things incorrectly or tell them what they don’t understand. Either one will cause them to move to a purely transactional relationship with you. And there’s no coming back from that.

When someone confides in you and shares their truth, you ask them to defend it, and, despite your unskillful response they share it again, believe them. And if you don’t, you’ll damn yourself twice.

When someone shares their truth and you listen without judging, you build trust.

When someone sends you a heartfelt email describing a dilemma and your response is to set up a meeting to gain a fuller understanding, you build trust.

When someone demonstrates the courage to share a truth that they know contradicts the mission, believe them. You’ll build trust.

When someone shares their truth, you have an opportunity to build trust or break it. Which will you choose?

Image credit — Christian Scheja

An open letter to company leaders: We’re still out of gas.

We’re still out of gas.

Corporate initiatives and reinvention are important, but so are the fundamentals of meeting customer orders and keeping the production lines running. And so is our emotional well-being.

We cannot do it all.

Our youngest children must go to daycare and elementary school, and that scares us. And when they get the sniffles, we have a difficult time knowing whether it’s the sniffles or Covid. And that creates stress for us. Though we faithfully show up every day, our children’s health is a concern for us. We still give 100%, but it isn’t as good as a couple of years ago. But it is our best.

Our children in high school and college are having a difficult time. In-person, not in-person, masks, no mask, and soon-to-be masks are all additional stressors to the already stressful high school and college dynamics. This is what we live with every day. Is college even worth it? Our kids aren’t sure and neither are we. But that doesn’t stop the expenses. This is what we have to deal with after a full day of work. It’s stressful and draining. And our batteries aren’t fully charged when we wake up in the morning. Yet, we come to work and give our best. Though we know our best isn’t as good as it used to be, it IS our best.

We can’t give more.

And there’s a war in Europe. And while that messes up the company’s financials, it also messes up our emotional state. People are being killed every day and we see the pictures on the web. This drains and debilitates us. We need some time to process all this.

Partisan politics are sucking the positivity out of our country, and it drains all of us.

We have less to give.

And climate change is here, and it’s scary. And we don’t know what to do. We didn’t travel for business over the last years, and we did okay. Why not save the cost and the carbon like we did over the last two years?

Respectfully submitted,

Your People

image credit — Nathan

Work Like You Matter

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When the outcome was different than you thought, there was uncertainty as the work was new.

When there was uncertainty, you knew there would be learning.

When you were afraid of learning, you were afraid to be wrong.

And when you were afraid to be wrong, you were really afraid about what people would think of you.

Would you rather wall off uncertainty to prevent yourself from being wrong or would you rather try something new?

If there’s a difference between what others think of you and what you think of yourself, whose opinion matters more?

Why does it matter what people think of you?

Why do you let their mattering block you from trying new things?

In the end, hold onto the fact that you matter, especially when you have the courage to be wrong.

“Oh no, what went wrong?” by Bennilover is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

Your core business is your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

The Core generates the revenue, but it also starves fledgling businesses so they never make it off the ground.

There’s a certainty with the Core because it builds on success, but its success sets the certainty threshold too high for new businesses. And due to the relatively high level of uncertainty of the new business (as compared to the Core) the company can’t find the gumption to make the critical investments needed to reach orbit.

The Core has generated profits over the decades and those profits have been used to create the critical infrastructure that makes its success easier to achieve. The internal startup can’t use the Core’s infrastructure because the Core doesn’t share. And the Core has the power to block all others from taking advantage of the infrastructure it created.

The Core has grown revenue year-on-year and has used that revenue to build out specialized support teams that keep the flywheel moving. And because the Core paid for and shaped the teams, their support fits the Core like a glove. A new offering with a new value proposition and new business model cannot use the specialized support teams effectively because the new offering needs otherly-specialized support and because the Core doesn’t share.

The Core pays the bills, and new ventures create bills that the Core doesn’t like to pay.

If the internal startup has to compete with the Core for funding, the internal startup will fail.

If the new venture has to generate profits similar to the Core, the venture will be a misadventure.

If the new offering has to compete with the Core for sales and marketing support, don’t bother.

If the fledgling business’s metrics are assessed like the Core’s metrics, it won’t fly, it will flounder.

If you try to run a new business from within the Core, the Core will eat it.

To work effectively with the Core, borrow its resources, forget how it does the work, and run away.

To protect your new ventures from the Core, physically separate them from the Core.

To protect your new businesses from the Core, create a separate budget that the Core cannot reach.

To protect your internal startup from the Core, make sure it needs nothing from the Core.

To accelerate the growth of the fledgling business, make it safe to violate the Core’s first principles.

To bolster the capability of your new business, move resources from the Core to the new business.

To de-risk the internal startup, move functional support resources from the Core to the startup.

To fund your new ventures, tax the Core. It’s the only way.

“Core Memory” by JD Hancock is licensed under CC BY 2.0

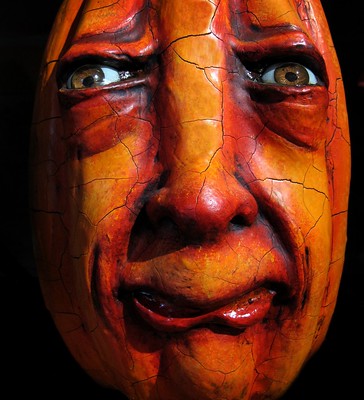

A Leading Indicator of Personal Growth — Fear

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

When was the last time you did something that scared you? And a more important follow-on question: How did you push through your fear and turn it into action?

Fear is real. Our bodies make it, but it’s real. And the feelings we create around fear are real, and so are the inhibitions we wrap around those feelings. But because we have the authority to make the fear, create the feelings, and wrap the inhibitions, we also have the authority to unmake, un-create, and unwrap.

Fear can feel strong. Whether it’s tightness in the gut, coldness in the chest, or lushness in the face, the physical manifestations in the body are recognizable and powerful. The sensations around fear are strong enough to stop us in our tracks. And in the wild of a bygone time, that was fear’s job – to stop us from making a mistake that would kill us. And though we no longer venture into the wild, fear responds to family dynamics, social situations, interactions at work, as if we still live in the wild.

To dampen the impact of our bodies’ fear response, the first step is to learn to recognize the physical sensations of fear for what they are – sensations we make when new situations arise. To do that, feel the sensations, acknowledge your body made them, and look for the novelty, or divergence from our expectations, that the sensations stand for. In that way, you can move from paralysis to analysis. You can move from fear as a blocker to fear as a leading indicator of personal growth.

Fear is powerful, and it knows how to create bodily sensations that scare us. But, that’s the chink in the armor that fear doesn’t want us to know. Fear is afraid to be called by name, so it generates these scary sensations so it can go on controlling our lives as it sees fit. So, next time you feel the sensations of fear in your body, welcome fear warmly and call it by name. Say something like, “Hello Fear. Thank you for visiting with me. I’d like to get to know you better. Can you stay for a coffee?”

You might find that Fear will engage in a discussion with you and apologize for causing you trouble. Fear may confess that it doesn’t like how it treats you and acknowledge that it doesn’t know how to change its ways. Or, it may become afraid and squirt more fear sensations into your body. If that happens, tell Fear that you understand it’s just doing what it evolved to do, and repeat your offer to sit with it and learn more about its ways.

The objective of calling Fear by name is to give you a process to feel and validate the sensations and then calm yourself by looking deeply at the novelty of the situation. By looking squarely into Fear’s eyes, it will slowly evaporate to reveal the nugget of novelty it was cloaking. And with the novelty in your sights, you can look deeply at this new situation (or context or interpersonal dynamic) and understand it for what it is. Without Fear’s distracting sensations, you will be pleasantly surprised with your ability to see the situation for what it is and take skillful action.

So, when Fear comes, feel the sensations. Don’t push them away. Instead, call Fear by name. Invite Fear to tell its story, and get to know it. You may find that accepting Fear for what it is can help you grow your relationship with Fear into a partnership where you help each other grow.

“tractor pull 02 – Arnegard ND – 2013-07-04” by Tim Evanson is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

If you “don’t know,” you’re doing it right.

If you know how to do it, it’s because you’ve done it before. You may feel comfortable with your knowledge, but you shouldn’t. You should feel deeply uncomfortable with your comfort. You’re not trying hard enough, and your learning rate is zero.

If you know how to do it, it’s because you’ve done it before. You may feel comfortable with your knowledge, but you shouldn’t. You should feel deeply uncomfortable with your comfort. You’re not trying hard enough, and your learning rate is zero.

Seek out “don’t know.”

If you don’t know how to do it, acknowledge you don’t know, and then go figure it out. Be afraid, but go figure it out. You’ll make mistakes, but without mistakes, there can be no learning.

No mistakes, no learning. That’s a rule.

If you’re getting pressure to do what you did last time because you’re good at it, well, you’re your own worst enemy. There may be good profits from a repeat performance, but there is no personal growth.

Why not find someone with “don’t know” mind and teach them?

Find someone worthy of your time and attention and teach them how. The company gets the profits, an important person gets a new skill, and you get the satisfaction of helping someone grow.

No learning, no growth. That’s a rule.

No teaching, no learning. That’s a rule, too.

If you know what to do, it’s because you have a static mindset. The world has changed, but you haven’t. You’re walking an old cowpath. It’s time to try something new.

Seek out “don’t know” mind.

If you don’t know what to do, it’s because you recognize that the old way won’t cut it. You know have a forcing function to follow. Follow your fear.

No fear, no growth. That’s a rule.

Embrace the “don’t know” mind. It will help you find and follow your fear. And don’t shun your fear because it’s a leading indicator of novelty, learning, and growth.

“O OUTRO LADO DO MEDO É A LIBERDADE (The Other Side of the Fear is the Freedom)” by jonycunha is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

When you don’t know the answer, what do you say?

When you are asked a question and you don’t know the answer, what do you say? What does that say about you?

When you are asked a question and you don’t know the answer, what do you say? What does that say about you?

What happens to people in your organization who say “I don’t know.”? Are they lauded or laughed at? Are they promoted, overlooked, or demoted? How many people do you know that have said: “I don’t know.”? And what does that say about your company?

When you know someone doesn’t know, what do you do? Do you ask them a pointed question in public to make everyone aware that the person doesn’t know? Do you ask oblique questions to raise doubt about the person’s knowing? Do you ask them a question in private to help them know they don’t know? Do you engage in an informal discussion where you plant the seeds of knowing? And how do you feel about your actions?

When you say “I don’t know.” you make it safe for others to say it. So, do you say it? And how do you feel about that?

When you don’t know and you say otherwise, decision quality suffers and so does the company. Yet, some companies make it difficult for people to say “I don’t know.” Why is that? Do you know?

I think it’s unreasonable to expect people to know the answer to know the answers to all questions at all times. And when you say “I don’t know.” it doesn’t mean you’ll never know; it means you don’t know at this moment. And, yet, it’s difficult to say it. Why is that? Do you know?

Just because someone asks a question doesn’t mean the answer must be known right now. It’s often premature to know the answer, and progress is not hindered by the not knowing. Why not make progress and figure out the answer when it’s time for the answer to be known? And sometimes the answer is unknowable at the moment. And that says nothing about the person that doesn’t know the answer and everything about the moment.

It’s okay if you don’t know the answer. What’s not okay is saying you know when you don’t. And it’s not okay if your company makes it difficult for you to say you don’t know. Not only does that create a demoralized workforce, but it’s also bad for business.

Why do companies make it so difficult to say “I don’t know.”? You guessed it – I don’t know.

“Question Mark Cookies 1” by Scott McLeod is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Trust-Based Disagreement

When there’s disagreement between words and behavior, believe the behavior. This is especially true when the words deny the behavior.

When there’s disagreement between the data and the decision, the data is innocent.

When there’s agreement that there’s insufficient data but a decision must be made, there should be no disagreement that the decision is judgment-based.

When there’s disagreement on the fact that there’s no data to support the decision, that’s a problem.

When there’s disagreement on the path forward, it’s helpful to have agreement on the process to decide.

When there’s disagreement among professionals, there is no place for argument.

When there’s disagreement, there is respect for the individual and a healthy disrespect for the ideas.

When there’s disagreement, the decisions are better.

When there’s disagreement, there’s independent thinking.

When there’s disagreement, there is learning.

When there’s disagreement, there is vulnerability.

When there’s disagreement, there is courage.

When there’s disagreement, there is trust.

“Teamwork” by davis.steve32 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski