Posts Tagged ‘Fear’

What do you believe about yourself?

If you believe you can’t do something, you can’t.

If you believe you can’t do something, you can’t.

If you try something and it doesn’t work, you might be able to pull it off next time.

If you believe you’re not good enough, you’re not.

If you try something and it doesn’t work, you’re still good enough.

If you believe someone’s opinion of you matters, it does.

If someone disparages you and you don’t believe it, they’re wrong.

If you believe you can do something, you can.

If you try something and it doesn’t work, try it again.

If you believe you’re good enough, you are.

If you try something and it doesn’t work, you have always been good enough.

If you believe someone’s opinion of you is none of your business, it isn’t.

If someone disparages you, ask them if they’re okay and ask if you can help them.

What do you believe?

What will you try next?

What will you do when someone disparages you?

Image credit — joiseyshowaa

Time is not coming back.

How much time do you spend on things you want to do?

How much time do you spend on things you don’t want to do?

How much time do you have left to change that?

If you’re spending time on things you don’t like, maybe it’s because you don’t have any better options. Sometimes life is like that.

But maybe there’s another reason you’re spending time on things you don’t like.

If you’re afraid to work on things you like, create the smallest possible project and try it in private.

If that doesn’t work, try a smaller project.

If you don’t know the ins and outs of the thing you like, give it a try on a small scale. Learn through trying.

If you don’t have a lot of money to do the thing you like, define the narrowest slice and give it a go.

If you could stop on one thing so you could start another, what are those two things? Write them down.

And start small. And start now.

Image credit — Pablo Monteagudo

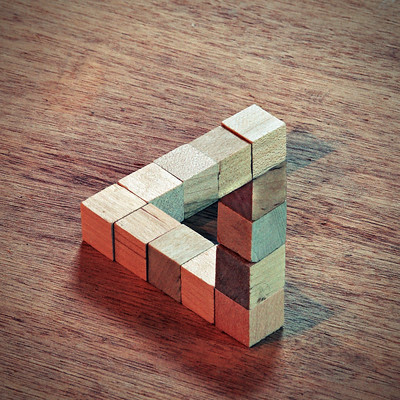

What’s in the way of the newly possible?

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

When “it’s impossible” it means it “cannot be done.” But maybe “impossible” means “We don’t yet know how to do it.” Or “We don’t yet know if others have done it before.”

What does it take to transition from impossible to newly possible? What must change to move from the impossible to the newly possible?

Context-Specific Impossibility. When something works in one industry or application but doesn’t work in another, it’s impossible in that new context. But usually, almost all the elements of the system are possible and there are one or two elements that don’t work due to the new context. There’s an entire system that’s blocked from possibility due to the interaction between one or two system elements and an environmental element of the new context. The path to the newly possible is found in those tightly-defined interactions. Ask yourself these questions: Which system elements don’t work and what about the environment is preventing the migration to the newly possible? And let the intersection focus your work.

History-Specific Impossibility. When something didn’t work when you tried it a decade ago, it was impossible back then based on the constraints of the day. And until those old constraints are revisited, it is still considered impossible today. Even though there has been a lot of progress over the last decades, if we don’t revisit those constraints we hold onto that old declaration of impossibility. The newly possible can be realized if we search for new developments that break the old constraints. Ask yourself: Why didn’t it work a decade ago? What are the new developments that could overcome those problems? Focus your work on that overlap between the old problems and the new developments.

Emotionally-Specific Impossibility. When you believe something is impossible, it’s impossible. When you believe it’s impossible, you don’t look for solutions that might birth the newly possible. Here’s a rule: If you don’t look for solutions, you won’t find them. Ask yourself: What are the emotions that block me from believing it could be newly possible? What would I have to believe to pursue the newly possible? I think the answer is fear, but not the fear of failure. I think the fear of success is a far likelier suspect. Feel and acknowledge the emotions that block the right work and do the right work. Feel the fear and do the work.

The newly possible is closer than you think. The constraints that block the newly possible are highly localized and highly context-specific. The history that blocks the newly possible is no longer applicable, and it’s time to unlearn it. Discover the recent developments that will break the old constraints. And the emotions that block the newly possible are just that – emotions. Yes, it feels like the fear will kill you, but it only feels like that. Bring your emotions with you as you do the right work and generate the newly possible.

image credit – gfpeck

Too Much of a Good Thing

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Product cost reduction is a good thing.

Too much focus on product cost reduction prevents product enhancements, blocks new customer value propositions, and stifles top-line growth.

Voice of the Customer (VOC) activities are good.

Because customers don’t know what’s possible, too much focus on VOC silences the Voice of the Technology (VOT), blocks new technologies, and prevents novel value propositions. Just because customers aren’t asking for it doesn’t mean they won’t love it when you offer it to them.

Standard work is highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company is focused on standard work, novelty is squelched, new ideas are scuttled, and new customer value never sees the light of day.

Best practices are highly effective and highly productive.

When your whole company defaults to best practices, novel projects are deselected, risk is radically reduced (which is super risky), people are afraid to try new things and use their judgment, new products are just like the old ones (no sizzle), and top-line growth is gifted to your competitors.

Consensus-based decision-making reduces bad decisions.

In domains of high uncertainty, consensus-based decision-making reduces projects to the lowest common denominator, outlaws the use of judgment and intuition, slows things to a crawl, and makes your most creative people leave the company.

Contrary to Mae West’s maxim, too much of a good thing isn’t always wonderful.

Image credit — Krassy Can Do It

What To Do When It Matters

If you see something that matters, say something.

If you see something that matters, say something.

If you say something and nothing happens, you have a choice – bring it up again, do something, or let it go.

Bring it up again when you think your idea was not understood. And if it’s still not understood after the second try, bring it up a third time. After three unsuccessful tries, stop bringing it up.

Now your choice is to do something or let it go.

Do something to help people see your idea differently. If it’s a product or technology, build a prototype and show people. This makes the concept more real and facilitates discussion that leads to new understanding and perspectives. If it’s a new value proposition, create a one-page sales tool that defines the new value from the customers’ perspective and show it to several customers. Make videos of the customers’ reactions and show them to people that matter. The videos let others experience the customers’ reactions first-hand and first-hand customer feedback makes a difference. If is a new solution to a problem, make a prototype of the solution and show it to people that have the problem. People with problems react well to solutions that solve them.

When people see you invest time to make a prototype or show a concept to customers, they take you and your concept more seriously.

If there’s no real traction after several rounds of doing something, let it go. Letting it go releases you from the idea and enables you to move on to something better. Letting it go allows you to move on. Don’t confuse letting it go with doing nothing. Letting it go is an action that is done overtly.

The number of times to bring things up is up to you. The number of prototypes to build is up to you. And the sequence is up to you. Sometimes it’s right to forgo prototypes and customer visits altogether and simply let it go.

But don’t worry. Because it matters to you, you’ll figure out the best way to move it forward. Follow your instincts and don’t look back.

Image credit – Peter Addor

Do you create the conditions for decisions to be made without you?

What does your team do when you’re not there? Do they make decisions or wait for you to come back so you can make them?

What does your team do when you’re not there? Do they make decisions or wait for you to come back so you can make them?

If your team makes an important decision while you’re out of the office, do you support or criticize them? Which response helps them stand taller? Which is most beneficial to the longevity of the company?

If other teams see your team make decisions while you are on vacation, doesn’t that make it easier for those other teams to use their good judgment when their leader is on vacation?

If a team waits for their leader to return before making a decision, doesn’t that slow progress? Isn’t progress what companies are all about?

When you’re not in the office, does the organization reach out directly to your team directly? Or do they wait until they can ask your permission? If they don’t reach out directly, isn’t that a reflection on you as the leader? Is your leadership helping or hindering progress? How about the professional growth of your team members?

Does your team know you want them to make decisions and use their best judgment? If not, tell them. Does the company know you want them to reach out directly to the subject matter experts on your team? If not, tell them.

If you want your company to make progress, create the causes and conditions for good decisions to be made without you.

Image credit – Conall

Are you making progress?

Just before it’s possible, it’s impossible.

Just before it’s possible, it’s impossible.

An instant before you know how to do it, you don’t.

After searching for the answer for a year, you may find it in the next instant.

If you stop searching, that’s the only way to guarantee you won’t find it.

When people say it won’t work, their opinion is valid only if nothing has changed since the last time, including the people and their approach.

If you know it won’t work, change the approach, the specification, or the scope.

If you think it won’t work, that’s another way of saying “it might work “.

If you think it might work, that’s another way of saying “it might not work”.

When there’s a difference of opinion, that’s objective evidence the work is new.

If everyone sees it the same way, you’re not trying hard enough.

When you can’t predict the project’s completion date, that’s objective evidence that the work is new.

If you know when the project will be done, the novelty has been wrestled out of the project or there was none at the start.

When you don’t start with the most challenging element of the project, you cause your company to spend a lot of money on a potentially nonviable project.

Until the novel elements of a project are demonstrated, there is no real progress.

“Jumping Backwards – Cape Verde, Sal Rei” by Espen Faugstad is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

What would you do differently if you believed in yourself more?

Belief in yourself manifests in your actions. What do your actions say about your belief in yourself?

Belief in yourself doesn’t mean everything will work out perfectly. It means that you’ll be okay regardless of how things turn out.

When you see someone that doesn’t believe in themselves, how do you feel? And what do you do?

And when that someone is you, how do you feel? And what do you do?

When someone believes in you more than you do, do you believe them?

You reach a critical threshold when your belief in yourself can withstand others’ judgment of you.

When you believe in yourself, you don’t define yourself by what others think of you.

When you love yourself more, you believe in yourself more.

If you had a stronger belief in yourself, what would you do differently?

Try this. Make a list of three things you’d do differently if you had a stronger belief in yourself. Then, find one of those special people that believe in you and show them your list. And whatever they say about your list, believe them.

Image credit — ajari

It’s good to have experience, until the fundamentals change.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

We use our previous experiences as context for decisions we make in the present. When we have a bad experience, the experience-context pair gets stored away in our memory so that we can avoid a similar bad outcome when a similar context arises. And when we have a good experience, or we’re successful, that memory-context pair gets stored away for future reuse. This reuse approach saves time and energy and, most of the time keeps us safe. It’s nature’s way of helping us do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

The system works well when we correctly match the historical context with today’s context and the system’s fundamentals remain unchanged. There are two potential failure modes here. The first is when we mistakenly map the context of today’s situation with a memory-context pair that does not apply. With this, we misapply our experience-based knowledge in a context that demands different knowledge and different decisions. The second (and more dangerous) failure mode is when we correctly identify the match between past and current contexts but the rules that underpin the context have changed. Here, we feel good that we know how things will turn out, and, at the same time, we’re oblivious to the reality that our experience-based knowledge is out of date.

“If a cat sits on a hot stove, that cat won’t sit on a hot stove again. That cat won’t sit on a cold stove either. That cat just don’t like stoves.” Mark Twain

If you tried something ten years ago and it failed, it’s possible that the underpinning technology has changed and it’s time to give it another try.

If you’ve been successful doing the same thing over the last ten years, it’s possible that the underpinning business model has changed and it’s time to give a different one a try.

“Hissing cat” by Consumerist Dot Com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

The first step is to admit you have a problem.

Nothing happens until the pain caused by a problem is greater than the pain of keeping things as they are.

Nothing happens until the pain caused by a problem is greater than the pain of keeping things as they are.

Problems aren’t bad for business. What’s bad for business is failing to acknowledge them.

The consternation that comes from the newly-acknowledged problem is the seed from which the solution grows.

There can be no solution until there’s a problem.

When the company doesn’t have a big problem, it has a bigger problem – complacency.

If you want to feel anxious about something, feel anxious that everything is going swimmingly.

Successful companies tolerate problems because they can.

Successful companies that tolerate their problems for too long become unsuccessful companies.

What happens to people in your company that talk about big problems? Are they celebrated, ignored, or ostracized? And what behavior does that reinforce? And how do you feel about that?

When everyone knows there’s a problem yet it goes unacknowledged, trust erodes.

And without trust, you don’t have much.

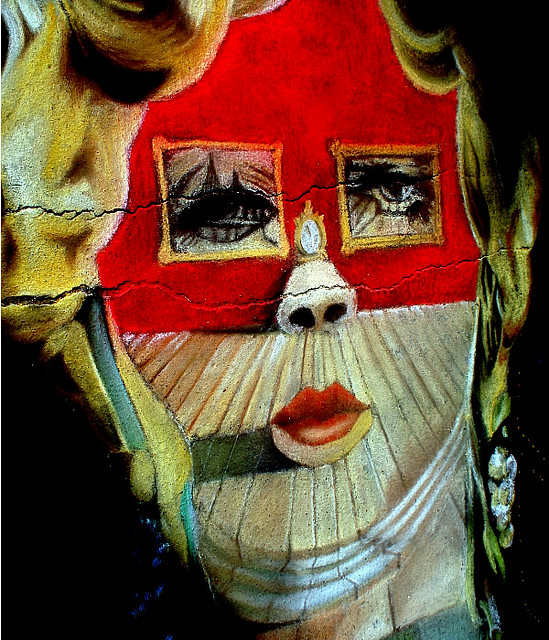

The Ins and Outs of Things

When things are overwhelming to you but not to others, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed for a while.

When things are overwhelming to you but not to others, it’s okay to feel overwhelmed for a while.

When the seas are rough, you may think you are alone, but others may see it differently.

What’s worthy of your attention is defined by you, though some make it easy for you to think otherwise.

When you disagree with someone’s idea, that says nothing about them.

Judging someone from the outside is unfair, and it’s the same with judging yourself from the inside.

When everyone around you sees you differently than you see yourself, it’s worth looking critically at what you see that they don’t and what they see that you don’t.

You aren’t your thoughts and feelings, but it can feel like it in the heat of the moment.

Self-judgment is the strongest flavor of judgment.

“Object from the exhibition We call them Vikings produced by The Swedish History Museum” by The Swedish History Museum, Stockholm is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski