Posts Tagged ‘Creativity’

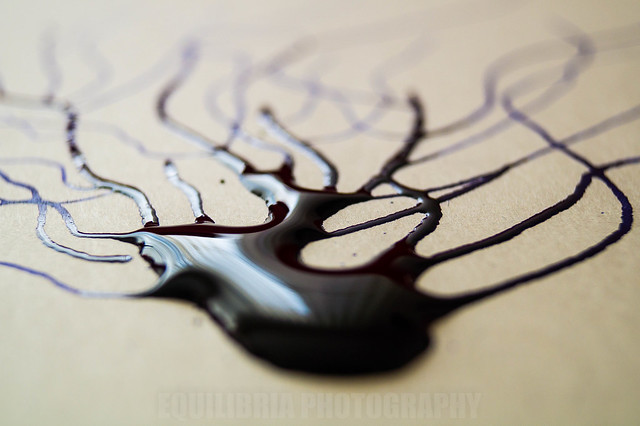

Seeing Things as They Can’t Be

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

When there’s a big problem, the first step is to define what’s causing it. To do that, based on an understanding of the physics, a sequence of events is proposed and then tested to see if it replicates the problem. In that way, the team must understand the system as it is before the problem can be solved.

Seeing things as they are. The same logic applies when it’s time to improve an existing product or service. The first thing to do is to see the system as it is. But seeing things as they are is difficult. We have a tendency to see things as we want them or to see them in ways that make us look good (or smart). Or, we see them in a way that justifies the improvements we already know we want to make.

To battle our biases and see things as they are, we use tools such as block diagrams to define the system as it is. The most important element of the block diagram is clarity. The first revision will be incorrect, but it must be clear and explicit. It must describe things in a way that creates a singular understanding of the system. The best block diagrams can be interpreted only one way. More strongly, if there’s ambiguity or lack of clarity, the thing has not yet risen to the level of a block diagram.

The block diagram evolves as the team converges on a single understanding of things as they are. And with a diagram of things as they are, a solution is readily defined and validated. If when tested the proposed solution makes the problem go away, it’s inferred that the team sees things as they are and the solution takes advantage of that understanding to make the problem go away.

Seeing things as they may be. Even whey the solution fixes the problem, the team really doesn’t know if they see things as they are. Really, all they know is they see things as they may be. Sure, the solution makes the problem go away, but it’s impossible to really know if the solution captures the physics of failure. When the system is large and has a lot of moving parts, the team cannot see things as they are, rather, they can only see the system as it may be. This is especially true if the system involves people, as people behave differently based on how they feel and what happened to them yesterday.

There’s inherent uncertainty when working with larger systems and systems that involve people. It’s not insurmountable, but you’ve got to acknowledge that your understanding of the system is less than perfect. If your company is used to solving small problems within small systems, there will be little tolerance for the inherent uncertainty and associated unpredictability (in time) of a solution. To help your company make the transition, replace the language of “seeing things as they are” with “seeing things as they may be.” The same diagnostic process applies, but since the understanding of the system is incomplete or wrong, the proposed solutions cannot not be pre-judged as “this will work” and “that won’t work.” You’ve got to be open to all potential solutions that don’t contradict the system as it may be. And you’ve got to be tolerant of the inherent unpredictability of the effort as a whole.

Seeing things as they could be. To create something that doesn’t yet exist, something does things like never before, something altogether new, you’ve got to stand on top of your understanding of the system and jump off. Whether you see things as they are or as they may be, the new system will be different. It’s not about diagnosing the existing system; it’s about imagining the system as it could be. And there’s a paradox here. The better you understand the existing system, the more difficulty you’ll have imagining the new one. And, the more success the company has had with the system as it is, the more resistance you’ll feel when you try to make the system something it could be.

Seeing things as they could be takes courage – courage to obsolete your best work and courage to divest from success. The first one must be overcome first. Your body creates stress around the notion of making yourself look bad. If you can create something altogether better, why didn’t you do it last time? There’s a hit to the ego around making your best work look like it’s not all that good. But once you get over all that, you’ve earned the right to go to battle with your organization who is afraid to move away from the recipe responsible for all the profits generated over the last decade.

But don’t look at those fears as bad. Rather, look at them as indicators you’re working on something that could make a real difference. Your ego recognizes you’re working on something better and it sends fear into your veins. The organization recognizes you’re working on something that threatens the status quo and it does what it can to make you stop. You’re onto something. Keep going.

Seeing things as they can’t be. This is rarified air. In this domain you must violate first principles. In this domain you’ve got to run experiments that everyone thinks are unreasonable, if not ill-informed. You must do the opposite. If your product is fast, your prototype must be the slowest. If the existing one is the heaviest, you must make the lightest. If your reputation is based on the highest functioning products, the new offering must do far less. If your offering requires trained operators, the new one must prevent operator involvement.

If your most seasoned Principal Engineer thinks it’s a good idea, you’re doing it wrong. You’ve got to propose an idea that makes the most experienced people throw something at you. You’ve got to suggest something so crazy they start foaming at the mouth. Your concepts must rip out their fillings. Where “seeing things as they could be” creates some organizational stress, “seeing things as they can’t be” creates earthquakes. If you’re not prepared to be fired, this is not the domain for you.

All four of these domains are valuable and have merit. And we need them all. If there’s one message it’s be clear which domain you’re working in. And if there’s a second message it’s explain to company leadership which domain you’re working in and set expectations on the level of uncertainty and unpredictability of that domain.

Image credit – David Blackwell.

Don’t change culture. Change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

At the highest level, you can make the biggest cultural change when you change how you spend your resources. Want to change culture? Say yes to projects that are different than last year’s and say no to the ones that rehash old themes. And to provide guidance on how to choose those new projects create, formalize new ways you want to deliver new value to new customers. When you change the criteria people use to choose projects you change the projects. And when you change the projects people’s behaviors change. And when behavior changes, culture changes.

The other important class of resources is people. When you change who runs the project, they change what work is done. And when they prioritize a different task, they prioritize different behavior of the teams. They ask for new work and get new behavior. And when those project leaders get to choose new people to do the work, they choose in a way that changes how the work is done. New project leaders change the high-level behaviors of the project and the people doing the work change the day-to-day behavior within the projects.

Change how projects are chosen and culture changes. Change who runs the projects and culture changes. Change who does the project work and culture changes.

Image credit – Eric Sonstroem

Innovation isn’t uncertain, it’s unknowable.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

With innovation, there can be no Marketing Brief because there are no customers, no product and no technology to underpin it. And the needs the innovation will satisfy are unknowable because customers have not asked for the them, nor can the customer understand the innovation if you showed it to them. And how the customers will use the? That’s unknowable because, again, there are no customers and no customer needs. And how many will you sell and the sales price? Again, unknowable.

Where’s the Specification? In product development, the Marketing Brief is translated into a Specification that defines what the product must do and how much it will cost. To define what the product must do, the Specification defines a set of test protocols and their measurable results. And the minimum performance is defined as a percentage improvement over the test results of the existing product.

With innovation, there can be no Specification because there are no customers, no product, no technology and no business model. In that way, there can be no known test protocols and the minimum performance criteria are unknowable.

Where’s the Schedule? In product development, the tasks are defined, their sequence is defined and their completion dates are defined. Because the work has been done before, the schedule is a lot like the last one. Everyone knows the drill because they’ve done it before.

With innovation, there can be no schedule. The first task can be defined, but the second cannot because the second depends on the outcome of the first. If the first experiment is successful, the second step builds on the first. But if the first experiment is unsuccessful, the second must start from scratch. And if the customer likes the first prototype, the next step is clear. But if they don’t, it’s back to the drawing board. And the experiments feed the customer learning and the customer learning shapes the experiments.

Innovation is different than product development. And success in product development may work against you in innovation. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to lock things down, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to write a specification, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. And if you are doing innovation and find yourself trying to nail down a completion date, you are definitely misapplying your product development expertise.

With innovation, people say the work is uncertain, but to me that’s not the right word. To me, the work is unknowable. The customer is unknowable because the work hasn’t been done before. The specification is unknowable because there is nothing for comparison. And the schedule in unknowable because, again, the work hasn’t been done before.

To set expectations appropriately, say the innovation work is unknowable. You’ll likely get into a heated discuss with those who want demand a Marketing Brief, Specification and Schedule, but you’ll make the point that with innovation, the rules of product development don’t apply.

Image credit — Fatih Tuluk

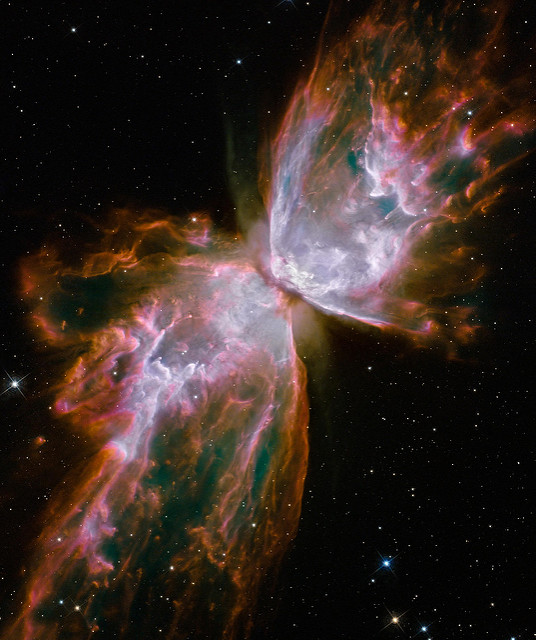

You’re probably not doing transformational work.

Continuous improvement is not transformation. With continuous improvement, products, processes and services are improved three percent year-on-year. With transformation, products are a mechanism to generate data, processes are eliminated altogether and services move from fixing what’s broken to proactive updates that deliver the surprising customer value.

A strategic initiative is not transformation. A strategic initiative improves a function or process that is – a move to consultative selling or a better new product development process. Transformation dismantles. The selling process is displaced by automatic with month-to-month renewals. And while product development is still a thing, it’s relegated to a process that creates the platform for the real money-maker – the novel customer value made possible by the data generated by the product.

Cultural change is not transformation. Cultural change uses the gaps in survey data to tweak a successful formula and adjust messaging. Transformation creates new organizations that violate existing company culture.

If there the corporate structure is unchanged, there can be no transformation.

If the power brokers are unchanged, there can be no transformation.

If the company culture isn’t violated, there can be no transformation.

If it’s not digital, there can be no transformation.

In short, if the same rules apply, there can be no transformation.

Transformation doesn’t generate discomfort, it generates disarray.

Transformation doesn’t tweak the successful, it creates the unrecognizable.

Transformation doesn’t change the what, it creates a new how.

Transformation doesn’t make better caterpillars, it creates butterflies.

Image credit – Chris Sorge

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

The primary impediment to innovation is fear, and the prime directive of any innovation system should be to drive out fear.

A culture of accountability, implemented poorly, can inject fear and deter innovation. When the team is accountable to deliver on a project but are constrained to a fixed scope, a fixed launch date and resources, they will be afraid. Because they know that innovation requires new work and new work is inherently unpredictable, they rightly recognize the triple accountability – time, scope and resources – cannot be met. From the very first day of the project, they know they cannot be successful and are afraid of the consequences.

A culture of accountability can be adapted to innovation to reduce fear. Here’s one way. Keep the team small and keep them dedicated to a single innovation project. No resource sharing, no swapping and no double counting. Create tight time blocks with clear work objectives, where the team reports back on a fixed pitch (weekly, monthly). But make it clear that they can flex on scope and level of completeness. They should try to do all the work within the time constraints but they must know that it’s expected the scope will narrow or shift and the level of completeness will be governed by the time constraint. Tell them you believe in them and you trust them to do their best, then praise their good judgement at the review meeting at the end of the time block.

Innovation is about solving new problems, yet fear blocks teams from trying new things. Teams like to solve problems that are familiar because they have seen previous teams judged negatively for missing deadlines. Here’s the logic – we’d rather add too little novelty than be late. The team would love to solve new problems but their afraid, based on past projects, that they’ll be chastised for missing a completion date that’s disrespectful of the work content and level of novelty. If you want the team to solve new problems, give them the tools, time, training and a teacher so they can select different problems and solve them differently. Simply put – create the causes and conditions for fear to quietly slink away so innovation will flow.

Fear is the most powerful inhibitor. But before we can lessen the team’s fear we’ve got to recognize the causes and conditions that create it. Fear’s job is to keep us safe, to keep us away from situations that have been risky or dangerous. To do this, our bodies create deep memories of those dangerous or scary situations and creates fear when it recognizes similarities between the current situation and past dangerous situations. In that way, less fear is created if the current situation feels differently from situations of the past where people were judged negatively.

To understand the causes and conditions that create fear, look back at previous projects. Make a list of the projects where project members were judged negatively for things outside their control such as: arbitrary launch dates not bound by the work content, high risk levels driven by unjustifiable specifications, insufficient resources, inadequate tools, poor training and no teacher. And make a list of projects where team members were praised. For the projects that praised, write down attributes of those projects (e.g., high reuse, low technical risk) and their outcomes (e.g., on time, on cost). To reduce fear, the project team will bend new projects toward those attributes and outcomes. Do the same for projects that judged negatively for things outside the project teams’ control. To reduce fear, the future project teams will bend away from those attributes and outcomes.

Now the difficult parts. As a leader, it’s time to look inside. Make a list of your behaviors that set (or contributed to) causes and conditions that made it easy for the project team to be judged negatively for the wrong reasons. And then make a list of your new behaviors that will create future causes and conditions where people aren’t afraid to solve new problems in new ways.

Image credit — andrea floris

Ask for the right work product and the rest will take care of itself.

We think we have more control than we really have. We imagine an idealized future state and try desperately to push the organization in the direction of our imagination. Add emotional energy, define a rational approach, provide the supporting rationale and everyone will see the light. Pure hubris.

We think we have more control than we really have. We imagine an idealized future state and try desperately to push the organization in the direction of our imagination. Add emotional energy, define a rational approach, provide the supporting rationale and everyone will see the light. Pure hubris.

What if we took a different approach? What if we believed people want to do the right thing but there’s something in the way? What if like a log jam in a fast-moving river, we remove the one log blocking them all? What if like a river there’s a fast-moving current of company culture that wants to push through the emotional log jam that is the status quo? What if it’s not a log at all but, rather, a Peter Principled executive that’s threatened by the very thing that will save the company?

The Peter Principled executive is a tough nut to crack. Deeply entrenched in the powerful goings on of the mundane and enabled by the protective badge of seniority, these sticks-in-the-mud need to be helped out of the way without threatening their no-longer-deserved status. Tricky business.

Rule 1: If you get into an argument with a Peter Principled executive, you’ll lose.

Rule 2: Don’t argue with Peter Principled executive.

If we want to make it easy for the right work to happen, we’ve got to learn how to make it easy for the Peter Principled executive to get out of the way. First, ask yourself why the executive is in the way. Why are they blocking progress? What’s keeping them from doing the right thing? Usually it comes down to the fear of change or the fear of losing control. Now it’s time to think of a work product that will help make the case there’s a a better way. Think of a small experiment to demonstrate a new way is possible and then run the experiment. Don’t ask, just run it. But the experiment isn’t the work product. The work product is a short report that makes it clear the new paradigm has been demonstrated, at least at small scale. The report must be clear and dense and provide objective evidence the right work happened by the right people in the right way. It must be written in a way that preempts argument – this is what happened, this is who did it, this is what it looks like and this is the benefit.

It’s critical to choose the right people to run the experiment and create the work product. The work must be done by someone in the chain of command of the in-the-way executive. Once the work product is created, it must be shared with an executive of equal status who is by definition outside the chain of command. From there, that executive must send a gracious email back into the chain of command that praises the work, praises the people who did it and praises the leader within the chain of command who had the foresight to sponsor such wonderful work.

As this public positivity filters through the organization, more people will add their praise of the work and the leaders that sponsored it. And by the time it makes it up the food chain to the executive of interest, the spider web of positivity is anchored across the organization and can’t be unwound by argument. And there you have it. You created the causes and conditions for the log jam to unjam itself. It’s now easy for the executive to get out of the way because they and their organization have already been praised for demonstrating the new paradigm. You’ve built a bridge across the emotional divide and made it easy for the executive and the status quo to cross it.

Asking for the right work product is a powerful skill. Most error on the side of complication and complexity, but the right work product is just the opposite – simple and tight. Think sledgehammer to the forehead in the form of and Excel chart where the approach is beyond reproach; where the chart can be interpreted just one way; where the axes are labeled; and it’s clear the status quo is long dead.

Business model is dead and we’ve got to stop trying to keep it alive. It’s time to break the log jam. Don’t be afraid. Create the right work product that is the dynamite that blows up the status quo and the executives clinging to it.

Image credit – Emilio Küffer

How To Design

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What do they want? Some get there with jobs-to-be-done, some use Customer Needs, some swear by ethnographic research and some like to understand why before what. But in all cases, it starts with the customer. Whichever mechanism you use, the objective is clear – to understand what they need. Because if you don’t know what they need, you can’t give it to them. And once you get your arms around their needs, you’re ready to translate them into a set of functional requirements, that once satisfied, will give them what they need.

What does it do? A complete set of functional requirements is difficult to create, so don’t start with a complete set. Use your new knowledge of the top customer needs to define and prioritize the top functional requirements (think three to five). Once tightly formalized, these requirements will guide the more detailed work that follows. The functional requirements are mapped to elements of the design, or design parameters, that will bring the functions to life. But before that, ask yourself if a check-in with some potential customers is warranted. Sometimes it is, but at these early stages it’s may best to wait until you have something tangible to show customers.

What does it look like? The design parameters define the physical elements of the design that ultimately create the functionality customers will buy. The design parameters define shape of the physical elements, the materials they’re made from and the interaction of the elements. It’s best if one design parameter controls a single functional requirement so the functions can be dialed in independently. At this early concept phase, a sketch or CAD model can be created and reviewed with customers. You may learn you’re off track or you may learn you’re way off track, but either way, you’ll learn how the design must change. But before that, take a little time to think through how the product will be made.

How to make it? The process variables define the elements of the manufacturing process that make the right shapes from the right materials. Sometimes the elements of the design (design parameters) fit the process variables nicely, but often the design parameters must be changed or rearranged to fit the process. Postpone this mapping at your peril! Once you show a customer a concept, some design parameters are locked down, and if those elements of the design don’t fit the process you’ll be stuck with high costs and defects.

How to sell it? The goodness of the design must be translated into language that fits the customer. Create a single page sales tool that describes their needs and how the new functionality satisfies them. And include a digital image of the concept and add it to the one-pager. Show document to the customer and listen. The customer feedback will cause you to revisit the functional requirements, design parameters and process variables. And that’s how it’s supposed to go.

Though I described this process in a linear way, nothing about this process is linear. Because the domains are mapped to each other, changes in one domain ripple through the others. Change a material and the functionality changes and so do the process variables needed to make it. Change the process and the shapes must change which, in turn, change the functionality.

But changes to the customer needs are far more problematic, if not cataclysmic. Change the customer needs and all the domains change. All of them. And the domains don’t change subtly, they get flipped on their heads. A change to a customer need is an avalanche that sweeps away much of the work that’s been done to date. With a change to a customer need, new functions must be created from scratch and old design elements must culled. And no one knows what the what the new shapes will be or how to make them.

You can’t hold off on the design work until all the customer needs are locked down. You’ve got to start with partial knowledge. But, you can check in regularly with customers and show them early designs. And you can even show them concept sketches.

And when they give you feedback, listen.

Image credit – Worcester Wired

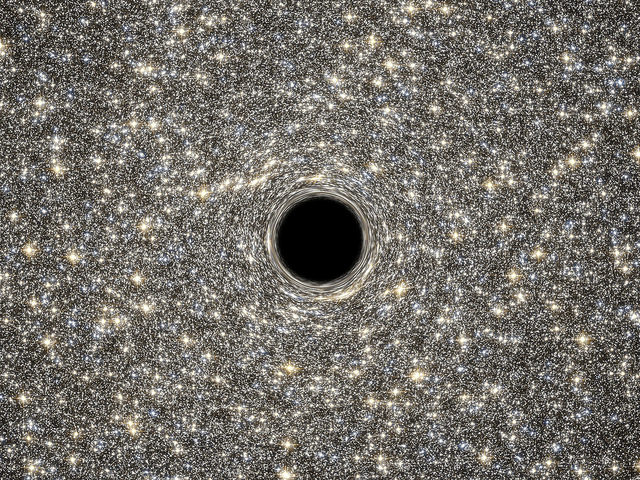

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

Image credit – NASA

A Little Uninterrupted Work Goes a Long Way

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

If your day doesn’t start with a list of things you want to get done, there’s little chance you’ll get them done. What if you spent thirty minutes to define what you want to get done and then spent an hour getting them done? In ninety minutes you’ll have made a significant dent in the most important work. It doesn’t sound like a big deal, but it’s bigger than big. Question: How often do you work for thirty minutes without interruptions?

Switching costs are high, but we don’t behave that way. Once interrupted, what if it takes ten minutes to get back into the groove? What if it takes fifteen minutes? What if you’re interrupted every ten or fifteen minutes? Question: What if the minimum time block to do real thinking is thirty minutes of uninterrupted time?

Let’s assume for your average week you carve out sixty minutes of uninterrupted time each day to do meaningful work, then, doing as I propose – spending thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing something meaningful every day – increases your meaningful work by 50%. Not bad. And if for your average week you currently spend thirty contiguous minutes each day doing deep work, the proposed ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 200%. A big deal. And if you only work for thirty minutes three out of five days, the ninety-minute arrangement increases your meaningful work by 400%. A night and day difference.

Question: How many times per week do you spend thirty minutes of uninterrupted time working on the most important things? How would things change if every day you spent thirty minutes planning and sixty minutes doing the most important work?

Great idea, but with today’s business culture there’s no way to block out ninety minutes of uninterrupted time. To that I say, before going to work, plan for thirty minutes at home. And set up a sixty-minute recurring meeting with yourself first thing every morning and do sixty minutes of uninterrupted work. And if you can’t sit at your desk without being interrupted, hold the sixty-minute meeting with yourself in a location where you won’t be interrupted. And, to make up for the thirty minutes you spent planning at home, leave thirty minutes early.

No way. Can’t do it. Won’t work.

It will work. Here’s why. Over the course of a month, you’ll have done at least 50% more real work than everyone else. And, because your work time is uninterrupted, the quality of your work will be better than everyone else’s. And, because you spend time planning, you will work on the most important things. More deep work, higher quality working conditions, and regular planning. You can’t beat that, even if it’s only sixty to ninety minutes per day.

The math works because in our normal working mode, we don’t spend much time working in an uninterrupted way. Do the math for yourself. Sum the number of minutes per week you spend working at least thirty minutes at time. And whatever the number, figure out a way to increase the minutes by 50%. A small number of minutes will make a big difference.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Space Flight Center

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

When you see emergent behavior that could grow into a powerful new theme, it’s important to acknowledge the behavior quickly and most publicly. If you see it in person, praise the behavior in front of everyone. Explain why you like it, explain why it’s important, explain what it could become. And as soon as you can find a computer, send an email to their bosses and copy the right-doers. Tell their bosses why you like it, tell them why it’s important, tell them what it could become.

Emergent behavior is like the first shoots of a beautiful orchid that may come to be. To the untrained eye, these little green beauties can look like scraggly weeds pushing out of the dirt. To the tired, overworked leader these new behaviors can like divergence, goofing around and even misbehavior. Without studying the leaves, the fledgling orchid can be confused for crabgrass.

Without initiative there is no new behavior and without new behavior there can be no orchids. When good people solve a problem in a creative way and it goes unacknowledged, the stem of the emergent behavior is clipped. But when the creativity is watered and fertilized the seedling has a chance to grow into something more. The leaders’ time and attention provide the nutrients, the leaders’ praise provides the hydration and their proactive advocacy for more of the wonderful behavior provides the sunlight to fuel the photosynthesis.

When the company demands bushels of grain, it’s a challenge to keep an eye out for the early signs of what could be orchids in the making. But that’s what a leader must do. More often than not, this emergent behavior, this magical behavior, goes unacknowledged if not unnoticed. As leaders, this behavior is unskillful. As leaders, we’ve got to slow down and pay more attention.

When you see the magic in emergent behavior, when you see the revolution it could grow into, and when you look someone in the eye and say – “I’ve got to tell you, what you did was crazy good. What you did could turn things upside down. What you did was inspiring. Thank you.” – you get people’s attention. Not only to do you get the attention of the person you’re talking to, you get the attention of everyone within a ten-foot radius. And thirty minutes later, almost everyone knows about the emergent behavior and the warm sunshine it attracted.

And, magically, without a corporate initiative or top-down deployment, over the next weeks there will be patches of orchids sprouting under desks, behind filing cabinets, on the manufacturing floor, in the engineering labs and in the common areas.

As leaders we must make it easier for new behavior to happen. We must figure a way to slow down and pay attention so we can recognize the seeds of could-be greatness. And to be able to invest the emotional energy needed to protect the seedlings, we must be well-rested. And like we know to provide the right soil, the right fertilizer, the right watering schedule and the right sunlight, we must remember that special behavior we want to grow is a result of causes and conditions we create.

Image credit – Rosemarie Crisasfi

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski