Posts Tagged ‘Creativity’

Rediscovering The Power of Getting Together In-Person

When you spend time with a group in person, you get to know them in ways that can’t be known if you spend time with them using electronic means. When meeting in person, you can tell when someone says something that’s difficult for them. And you can also tell when that difficulty is fake. When using screens, those two situations look the same, but, in person, you know they are different. There’s no way to quantify the value of that type of discernment, but the value borders on pricelessness.

When you spend time with a group in person, you get to know them in ways that can’t be known if you spend time with them using electronic means. When meeting in person, you can tell when someone says something that’s difficult for them. And you can also tell when that difficulty is fake. When using screens, those two situations look the same, but, in person, you know they are different. There’s no way to quantify the value of that type of discernment, but the value borders on pricelessness.

When people know you see them as they really are, they know you care. And they like that because they know your discernment requires significant effort. Sure, at first, they may be uncomfortable because you can see them as they are, but, over time, they learn that your ability to see them as they are is a sign of their importance. And there’s no need to call this out explicitly because all that learning comes as a natural byproduct of meeting in person.

And the game changes when people know you see them (and accept them) for who they are. The breadth of topics that can be discussed becomes almost limitless. Personal stories flow; family experiences bubble to the surface; misunderstandings are discussed openly; vulnerable thoughts and feelings are safely expressed; and trust deepens.

I think we’ve forgotten the power of working together in person, but it only takes three days of in-person project work to help us remember. If you have an important project deliverable, I suggest you organize a three-day, in-person event where a small group gets together to work on the deliverable. Create a formal agenda where it’s 50% work and 50% not work. (I’ve found that the 50% not work is the most valuable and productive.) Make it focused and make it personal. Cook food for the group. Go off-site to a museum. Go for a hike. And work hard. But, most importantly, spend time together.

Things will be different after the three-day event. Sure, you’ll make progress on your project deliverable, but, more importantly, you’ll create the conditions for the group to do amazing work over the next five years.

“Elephants Amboseli” by blieusong is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0.

Free Resources

Since resources are expensive, it can be helpful to see the environment around your product as a source of inexpensive resources that can be modified to perform useful functions. Here are some examples.

Since resources are expensive, it can be helpful to see the environment around your product as a source of inexpensive resources that can be modified to perform useful functions. Here are some examples.

Gravity is a force you can use to do your bidding. Since gravity is always oriented toward the center of the earth, if you change the orientation of an object, you change the direction gravity exerts itself relative to the object. If you flip the object upside down, gravity will push instead of pull.

And it’s the same for buoyancy but in reverse. If you submerge an object of interest in water and add air (bubbles) from below, the bubbles will rise and push in areas where the bubbles collect. If you flip over the object, the bubbles will collect in different areas and push in the opposite direction relative to the object.

And if you have water and bubbles, you have a delivery system. Add a special substance to the air which will collect at the interface between the water and air and the bubbles will deliver it northward.

If you have motion, you also have wind resistance or drag force (but not in deep space). To create more force, increase speed or increase the area that interacts with the moving air. To change the direction of the force relative to the object, change the orientation of the object relative to the direction of motion.

If you have water, you can also have ice. If you need a solid substance look to the water. Flow water over the surface of interest and pull out heat (cool) where you want the ice to form. With this method, you can create a protective coating that can regrow as it gets worn off.

If you have water, you can make ice to create force. Drill a blind hole in a piece of a brittle material (granite), fill the hole with water, and freeze the water by cooling the granite (or leave it outside in the winter). When the water freezes it will expand, push on the granite and break it.

These are some contrived examples, but I hope they help you see a whole new set of free resources you can use to make your magic.

Thank you, VF.

Image credit – audi_insperation

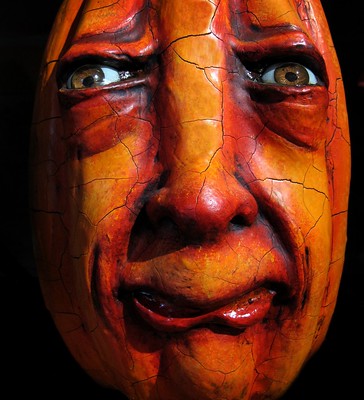

Triangulation of Leadership

Put together things that contradict yet make a wonderfully mismatched pair.

Say things that contradict common misunderstandings.

See the dark and dirty underside of things.

Be more patient with people.

Stomp on success.

Dissent.

Tell the truth even when it’s bad for your career.

See what wasn’t but should have been.

Violate first principles.

Protect people.

Trust.

See things as they aren’t.

See what’s missing.

See yourself.

See.

“man in park (triangulation)” by Josh (broma) is licensed under CC BY 2.0.

Work Like You Matter

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When you were wrong, the outcome was different than you thought.

When the outcome was different than you thought, there was uncertainty as the work was new.

When there was uncertainty, you knew there would be learning.

When you were afraid of learning, you were afraid to be wrong.

And when you were afraid to be wrong, you were really afraid about what people would think of you.

Would you rather wall off uncertainty to prevent yourself from being wrong or would you rather try something new?

If there’s a difference between what others think of you and what you think of yourself, whose opinion matters more?

Why does it matter what people think of you?

Why do you let their mattering block you from trying new things?

In the end, hold onto the fact that you matter, especially when you have the courage to be wrong.

“Oh no, what went wrong?” by Bennilover is marked with CC BY-ND 2.0.

Three Things for the New Year

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Next year will be different, but we don’t know how it will be different. All we know is that it will be different.

Some things will be the same and some will be different. The trouble is that we won’t know which is which until we do. We can speculate on how it will be different, but the Universe doesn’t care about our speculation. Sure, it can be helpful to think about how things may go, but as long as we hold on to the may-ness of our speculations. And we don’t know when we’ll know. We’ll know when we know, but no sooner. Even when the Operating Plan declares the hardest of hard dates, the Universe sets the learning schedule on its own terms, and it doesn’t care about our arbitrary timelines.

What to do?

Step 1. Try three new things. Choose things that are interesting and try them. Try to try them in parallel as they may interact and inform each other. Before you start, define what success looks like and what you’ll do if they’re successful and if they’re not. Defining the follow-on actions will help you keep the scope small. For things that work out, you’ll struggle to allocate resources for the next stages, so start small. And if things don’t work out, you’ll want to say that the projects consumed little resources and learned a lot. Keep things small. And if that doesn’t work, keep them smaller.

Step 2. Rinse and repeat.

I wish you a happy and safe New Year. And thanks for reading.

Mike

“three” by Travelways.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0

If you want to understand innovation, understand novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

Novelty is the difference between how things are today and how they might be tomorrow. And that comparison calibrates tomorrow’s idea within the context of how things are today. And that makes all the difference. When you can define how something is novel, you have an objective measure of things.

How is it different than what you did last time? If you don’t know, either you don’t know what you did last time or you don’t know the grounding principle of your new idea. Usually, it’s a little of the former and a whole lot of the latter. And if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t learn how potential customers will react to the novelty. In fact, if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t even decide who are the right potential customers.

A new idea can be novel in unique ways to different customer segments and it can be novel in opposite ways to intermediaries or other partners in the business model. A customer can see the novelty as something that will make them more profitable and an intermediary can see that same novelty as something that will reduce their influence with the customer and lead to their irrelevance. And, they’ll both be right.

Novelty is in the eye of the beholder, so you better look at it from their perspective.

Like with hot sauce, novelty comes in a range of flavors and heat levels. Some novelty adds a gentle smokey flavor to your favorite meal and makes you smile while the ghost pepper variety singes your palate and causes you to lose interest in the very meal you grew up on. With novelty, there is no singular level of Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) that is best. You’ve got to match the heat with the situation. Is it time to improve things a bit with a smokey, yet subtle, chipotle? Or, is it time to submerge things in pure capsaicin and blow the roof off? The good news is the bad news – it’s your choice.

With novelty, you can choose subtle or spicy. Choose wisely.

And like with hot sauce, novelty doesn’t always mix well with everything else on the plate. At the picnic, when you load your plate with chicken wings, pork ribs, and apple pie, it’s best to keep the hot sauce away from the apple pie. Said more strongly, with novelty, it’s best to use separate plates. Separate the teams – one team to do heavy novelty work, the disruptive work, to obsolete the status quo, and a separate team to the lighter novelty work, the continuous improvement work, to enhance the existing offering.

Like with hot sauce, different people have different tolerance levels for novelty. For a given novelty level, one person can be excited while another can be scared. And both are right. There’s no sense in trying to change a person’s tolerance for novelty, they either like it or they don’t. Instead of trying to teach them to how to enjoy the hottest hot sauce, it’s far more effective to choose people for the project whose tolerance for novelty is in line with the level of novelty required by the project.

Some people like habanero hot sauce, and some don’t. And it’s the same with novelty.

How to Decide if Your Problem is Worth Solving

How to decide if a problem is worth solving?

How to decide if a problem is worth solving?

If it’s a new problem, try to solve it.

If it’s a problem that’s already been solved, it can’t be a new problem. Let someone else re-solve it.

If a new problem is big, solve it in a small way. If that doesn’t work, try to solve it in a smaller way.

If there’s a consensus that the problem is worth solving, don’t bother. Nothing great comes from consensus.

If the Status Quo tells you not to solve it, you’ve hit paydirt!

If when you tell people about solving the problem they laugh, you’re onto something.

If solving the problem threatens the experts, double down.

If solving the problem obsoletes your most valuable product, solve it before your competition does.

If solving the problem blows up your value proposition, light the match.

If solving the problem replaces your product with a service, that’s a recipe for recurring revenue.

If solving the problem frees up a factory, well, now you have a free factory to make other things.

If solving the problem makes others look bad, that’s why they’re trying to block you from solving it.

If you want to know if you’re doing it right, make a list of the new problems you’ve tried to solve.

If your list is short, make it longer.

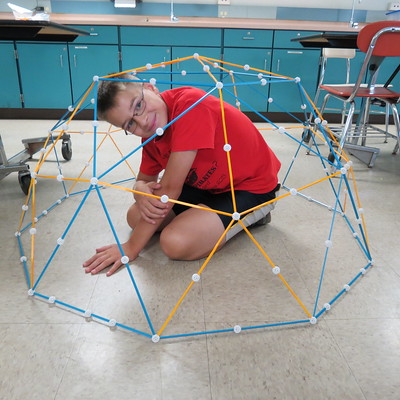

“CERDEC Math and Science Summer Camp, 2013” by CCDC_C5ISR is licensed under CC BY 2.0

If nine out of ten projects projects fail, you’re doing it wrong.

For work that has not been done before, there’s no right answer. The only wrong answer is to say “no” to trying something new. Sure, it might not work. But, the only way to guarantee it won’t work is to say no to trying.

For work that has not been done before, there’s no right answer. The only wrong answer is to say “no” to trying something new. Sure, it might not work. But, the only way to guarantee it won’t work is to say no to trying.

If innovation projects fail nine out of ten times, you can increase the number of projects you try or you can get better at choosing the projects to say no to. I suggest you say learn to say yes to the one in ten projects that will be successful.

If you believe that nine out of ten innovation projects will fail, you shouldn’t do innovation for a living. Even if true, you can’t have a happy life going to work every day with a ninety percent chance of failure. That failure rate is simply not sustainable. In baseball, the very best hitters of all time were unsuccessful sixty percent of the time, yet, even they focused on the forty percent of the time they got it right. Innovation should be like that.

If you’ve failed on ninety percent of the projects you’ve worked on, you’ve probably been run out of town at least several times. No one can fail ninety percent of the time and hold onto their job.

If you’ve failed ninety percent of the time, you’re doing it wrong.

If you’ve failed ninety percent of the time, you’ve likely tried to solve the wrong problems. If so, it’s time to learn how to solve the right problems. The right problems have two important attributes: 1) People will pay you if they are solved. 2) They’re solvable. I think we know a lot about the first attribute and far too little about the second. The problem with solvability is that there’s no partial credit, meaning, if a problem is almost solvable, it’s not solvable. And here’s the troubling part: if a problem is almost solved, you get none of the money. I suggest you tattoo that one on your arm.

As a subject matter expert, you know what could work and what won’t. And if you don’t think you can tell the difference, you’re not a subject matter expert.

Here’s a rule to live by: Don’t work on projects that you know won’t work.

Here’s a corollary: If your boss asks you to work on something that won’t work, run.

If you don’t think it will work, you’re right, even if you’re not.

If it might work, that’s about right. If it will work, let someone else do it. If it won’t work, run.

If you’ve got no reason to believe it will work, it won’t.

If you can’t imagine it will work, it won’t.

If someone else says it won’t work, it might.

If someone else tries to convince you it won’t work, they may have selfish reasons to think that way.

It doesn’t matter if others think it won’t work. It matters what you think.

So, what do you think?

If you someone asks you to believe something you don’t, what will you do?

If you try to fake it until you make it, the Universe will make you pay.

If you think you can outsmart or outlast the Universe, you can’t.

If you have a bad feeling about a project, it’s a bad project.

If others tell you that it’s a bad project, it may be a good one.

Only you can decide if a project is worth doing.

It’s time for you to decide.

“Good example of Crossfit Weight lifting – In Crossfit Always lift until you reach the point of Failure or you tear something” by CrossfitPaleoDietFitnessClasses is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Some Problems With Problems

If you don’t know what the problem is, that’s your first problem.

If you don’t know what the problem is, that’s your first problem.

A problem can’t be a problem unless there’s a solution. If there’s no possible solution, don’t try to solve it, because it’s not a problem.

If there’s no problem, you have a big problem.

If you’re trying to solve a problem, but the solution is outside your sphere of influence, you’re taking on someone else’s problem.

If someone tries to give you a gift but you don’t accept it, it’s still theirs. It’s like that with problems.

If you want someone to do the right thing, create a problem for them that, when solved, the right thing gets done.

Problems are good motivators and bad caretakers.

A problem is between two things, e.g., a hammer and your thumb. Your job is to figure out the right two things.

When someone tries to give you their problem, keep your hands in your pockets.

A problem can be solved before it happens, while it happens, or after it happened. Each time domain has different solutions, different costs, and different consequences. Your job is to choose the most appropriate time domain.

If you have three problems, solve one at a time until you’re done.

Solving someone else’s problem is a worst practice.

If you solve the wrong problem, you consume all the resources needed to solve the right problem without any of the benefits of solving it.

Ready, fire, aim is no way to solve problems.

When it comes to problems, defining IS solving.

If you learn one element of problem-solving, learn to see when someone is trying to give you their problem.

“My first solved Rubik’s cube” by Nina Stawski is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Continuous Improvement Is Dead

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time, just three percent better, so none of your people can try new things.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time, just three percent better, so none of your people can try new things.

Discontinuous Improvement – Make a radical step-change in performance at the expense of continuously improving it.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so you can say “no” to projects that are magical.

No-To-Yes – Make the product do something it cannot. That way you can sell a new value proposition to new customers and new markets. And you can threaten those that are clinging to your tired value proposition.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so no one will be threatened by meaningful change.

Less With Far Less – Reduce the goodness of today’s offering to free up design space and create an entirely new offering that provides 80% of the goodness at 20% of the price. That way, you can sell a whole new family of offerings to customers that cannot buy today’s offering.

Continuous Improvement – Do what you did last time so we can rest on our laurels.

Obsolete Your Best Work – Design and commercialize new offerings that purposefully make obsolete your most profitable offering. This requires level 5 courage.

And how do you do all this? Mobilize the Trust Network.

“fear — may 9 (day 9)” by theogeo is licensed under CC BY 2.0

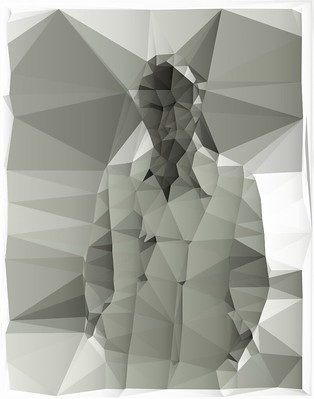

The Innovation Mantra

We have an immense distaste for uncertainty. And, as a result, we create for ourselves a radical and unskillful overestimation of our ability to control things. Our distaste of uncertainty is really a manifestation of our fear of death. When we experience and acknowledge uncertainty, it’s an oblique reminder that we will die. And that’s why talk ourselves into the belief we can control thing we really cannot. It’s a defense mechanism that creates distance between ourselves and from feeling our fear of death. And it’s the obliquity that makes it easier to overestimate our ability to control our environment. Without the obliquity, it’s clear we can’t control our environment, the very thing we wake up to every morning, and it’s clear we can’t control much. And if we can’t control much, we can’t control our aging and our ultimate end. And this is why we reject uncertainty at all costs.

We have an immense distaste for uncertainty. And, as a result, we create for ourselves a radical and unskillful overestimation of our ability to control things. Our distaste of uncertainty is really a manifestation of our fear of death. When we experience and acknowledge uncertainty, it’s an oblique reminder that we will die. And that’s why talk ourselves into the belief we can control thing we really cannot. It’s a defense mechanism that creates distance between ourselves and from feeling our fear of death. And it’s the obliquity that makes it easier to overestimate our ability to control our environment. Without the obliquity, it’s clear we can’t control our environment, the very thing we wake up to every morning, and it’s clear we can’t control much. And if we can’t control much, we can’t control our aging and our ultimate end. And this is why we reject uncertainty at all costs.

Predictable, controllable, repeatable, measurable – overt rejections of uncertainty. Six Sigma – Measure, Analyze, Improve, Control – overt rejection of uncertainty. Standard work – rejection of uncertainty. Don’t change the business model – a rejection of uncertainty. A rejection of novelty is a rejection of uncertainty. And that’s why we don’t like novelty. It scares us deeply. And it scares us because it reminds us that everything changes, including our skin, joints, and hairline. And that’s why it’s so challenging to do innovation.

Innovation reminds us of our death and that’s why it’s difficult? Really? Yes.

Six Sigma is comforting because its programmatic illusion of control lets us forget about our death? Yes.

The aging business model reminds us of our death and that’s why we won’t let it go? Yes.

That’s crazy! Yes, but at the deepest level, I think it’s true.

I understand if you disagree with my rationale. And I understand if you think my thinking is morbid. If that’s the case, I suggest you write down why you think it’s so incredibly difficult to create a new business model, to do novel work, or to obsolete your best work. I’ll stop for a minute to give you time to grab a pen and paper. Okay, now put your pen to paper and write down why doing innovation (doing novel work) is so difficult. Now, ask yourself why that is. And do that three more times. Where did you end up? What’s the fundamental reason why doing new work (and the uncertainty that comes with it) is so difficult to do?

To be clear, I’m not advocating that you tell everyone that innovation is difficult because it reminds them that they’ll die. I explained my rationale to give you an idea of the magnitude of the level of fear around uncertainty so that, when someone is scared to death of novelty, you might help them navigate their fear.

Trying something new doesn’t invalidate what you did over the last decade to grow your business, nor will it replace it immediately, if it all. Maybe the new work will add to what you’ve done over the last decade. Maybe the new work will amplify what’s made you successful. Maybe the new work will slowly and effectively migrate your business to greener pastures. And maybe it won’t work at all. Or, maybe your customers will make it work and bury you and your business.

With innovation, start small. That way the threat is smaller. Run small experiments and share the results, especially the bad results. That way you demonstrate that unanticipated results don’t kill you and, when you share them, you demonstrate that you’re not afraid of uncertainty. Try many things in parallel to demonstrate that it’s okay that everything doesn’t turn out well and you’re okay with it. And when someone asks what you’ll do next, tell them “I don’t know because it depends on how the next experiment turns out.”

When you’re asked when you’ll be done with an innovation project, tell them “I don’t know because the work has never been done before.” And if they say you must give them a completion date, tell them “If you must have a completion date, you do the project.”

When you’re running multiple experiments in parallel and you’re asked what you’ll do next, tell them you’ll do “more of what works and less of what doesn’t.” And if they say “that’s not acceptable”, then tell them “Well, then you run the project.”

We don’t have nearly as much control as our minds want to us believe, but that’s okay as long as we behave like we know it’s true. Uncertainty is uncomfortable, but that’s not a bad thing. In fact, I think it’s a good thing.

If people aren’t afraid, there can be no uncertainty. And if there’s no uncertainty, there can be no novelty. And if there’s no novelty, there can be no innovation. If people aren’t afraid, you’re doing it wrong.

As a leader, tell them you’re afraid but you’re going to do it anyway.

As a leader, tell your team that it’s natural to be afraid and their fear is a leading indicator of innovation.

As a leader, tell them there’s one thing you’re certain about – that innovation is uncertain.

And when things get difficult, repeat the Innovation Mantra: Be afraid and do it anyway.

“Mantra” by j / f / photos is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski