Posts Tagged ‘Competitiveness’

Before solving, learn more about the problem.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Is the problem big enough? There’s no sense spending the time and money to solve a problem unless you have a good idea the payback is worth the cost. Before spending the money to create the solution, spend the time to assess the benefits that will come from solving the problem.

Before you can decide if the problem is big enough, you have to define the problem and know who has it. One of the best ways to do this is to define how things are done today. Draw a block diagram that defines the steps potential customers follow or draw a picture of how they do things today. Define the products/services they use today and ask them what it would mean if you solved their problem. What’s particularly difficult at this point is they may not know they have a problem.

But before moving on, formalize who has the problem. Define the attributes of the potential customers and figure out how many have the same attributes and, possibly, the same problem. Define the segments narrowly to make sure each segment does, in fact, have the same problem. There will be a tendency to paint with broad strokes to increase the addressable market, but stay narrow and maintain focus on a tight group of potential customers.

Estimate the value of the solution based on how it compares to the existing alternative. And the only ones who can give you this information are the potential customers. And the only way they can give you the information is if you interview them and watch them work. And with this detailed knowledge, figure out the number of potential customers who have the problem. Do all this BEFORE any solving.

Will they pay for it? The only way to know if potential customers will pay for your solution is to show them an offering – a description of your value proposition and how it differs from the existing alternatives, a demo (a mockup of a solution and not a functional prototype) and pricing. (See LEANSTACK for more on an offering.) There will be a tendency to wait until the solution is ready, but don’t wait. And there will be a reluctance attach a price to the solution, but that’s the only way you’ll know how much they value your solution. And there will be difficulty defining a tight value proposition because that requires you to narrowly define what the solution does for the potential customer. And that’s scary because the value proposition will be clear and understandable and the potential customer will understand it well enough to decide they if they like it or not.

If you don’t assign a price and ask them to buy it, you’ll never know if they’ll buy it in real life.

Can you deliver it? List all the elements that must come together. Can you make it? Can you sell it? Can you ship it? Can you service it? Are your partners capable and committed? Do you have the money do put everything in place?

Like with a chain, it takes one bad link to make the whole thing fall apart. Figure out if any of your links are broken or missing. And don’t commit resources until they’re all in place and ready to go.

Image credit — Matthias Ripp

Growth Isn’t The Answer

Most companies have growth objectives – make more, sell more and generate more profits. Increase profit margin, sell into new markets and twist our products into new revenue. Good news for the stock price, good news for annual raises and plenty of money to buy the things that will help us grow next year. But it’s not good for the people that do the work.

Most companies have growth objectives – make more, sell more and generate more profits. Increase profit margin, sell into new markets and twist our products into new revenue. Good news for the stock price, good news for annual raises and plenty of money to buy the things that will help us grow next year. But it’s not good for the people that do the work.

To increase sales the same sales folks will have to drive more, call more and do more demos. Ten percent more work for three percent more compensation. Who really benefits here? The worker who delivers ten percent more or the company that pays them only three percent more? Pretty clear to me it’s all about the company and not about the people.

To increase the number of units made implies that there can be no increase in the number of people required to make them. To increase throughput without increasing headcount, the production floor will have less time for lunch, less time for improving their skills and less time to go to the bathroom. Sure, they can do Lean projects to eliminate waste, as long as they don’t miss their daily quota. And sure, they can help with Six Sigma projects to reduce variation, as long as they don’t miss TAKT time. Who benefits more – the people or the company?

Increased profit margin (or profit percentage) is the worst offender. There are only two ways to improve the metric – sell it for more or make it for less. And even better than that is to sell it for more AND make it for less. No one can escape this metric. The sales team must meet with more customers; the marketing team must work doubly hard to define and communicate the value proposition; the engineering staff must reduce the time to launch the product and make it perform better than their best work; and everyone else must do more with less or face the chopping block.

In truth, corporate growth is the fundamental behind global warming, reduced life expectancy in the US and the ridiculous increase in the cost of healthcare. Growth requires more products and more products require more material mined, pumped or clear-cut from the planet. Growth puts immense pressure on the people doing the work and increases their stress level. And when they can’t deliver, their deep sense of helplessness and inadequacy causes them to kill themselves. And healthcare costs increase because the companies within (and insuring) the system need to make more profit. Who benefits here? The people in our community? The people doing the work? The planet? Or the companies?

What if we decided that companies could not grow? What if instead companies paid dividends to the people do the work based on the profit the company makes? With constant output wouldn’t everyone benefit year-on-year?

What if we decided output couldn’t grow? What if instead, as productivity increased, companies required people to work fewer hours? What if everyone could make the same number of products in seven hours and went home an hour early, working seven and getting paid for eight? Would everyone be better off? Wouldn’t the planet be better off?

What if we decided the objective of companies was to employ more people and give them a sense of purpose and give meaning to their lives? What if we used the profit created by productivity improvements to employ more people? Wouldn’t our communities benefit when more people have good jobs? Wouldn’t people be happier because they can make a contribution to their community? Wouldn’t there be less stress and fewer suicides when parents have enough money to feed their kids and buy them clothes? Wouldn’t everyone benefit? Wouldn’t the planet benefit?

Year-on-year growth is a fallacy. Year-on-year growth stresses the planet and the people doing the work. Year-on-year growth is good for no one except the companies demanding year-on-year growth.

The planet’s resources are finite; people’s ability to do work is finite; and the stress level people can tolerate is finite. Why not recognize these realities?

And why not figure out how to structure companies in a way that benefits the owners of the company, the people doing the work, the community where the work is done and the planet?

Image credit – Ryan

Important Questions for Innovation

Here are some important questions for innovation.

Here are some important questions for innovation.

What’s the Distinctive Value Proposition? The new offering must help the customer make progress. How does the customer benefit? How is their life made easier? How does this compare to the existing offerings? Summarize the difference on one page. If the innovation doesn’t help the customer make progress, it’s not an innovation.

Is it too big or too small? If the project could deliver sales growth that would dwarf the existing sales numbers for the company, the endeavor is likely too big. The company mindset and philosophy would have to be destroyed. Are you sure you’re up to the challenge? If the project could deliver only a small increase in sales, it’s likely not worth the time and expense. Think return on investment. There’s no right answer, but it’s important to ask the question and set the limits for too big and too small. If it could grow to 10% of today’s sales numbers, that’s probably about right.

Why us? There’s got to be a reason why you’re the right company to do this new work. List the company’s strengths that make the work possible. If you have several strengths that give you an advantage, that’s great. And if one of your weaknesses gives you an advantage, that works too. Step on the accelerator. If none of your strengths give you an advantage, choose another project.

How do we increase our learning rate? First thing, define Learning Objectives (LOs). And once defined, create a plan to achieve them quickly. Here’s a hint. Define what it takes to satisfy the LOs. Here’s another hind. Don’t build a physical prototype. Instead, create a website that describes the potential offering and its value proposition and ask people if they want to buy it. Collect the data and refine the offering based on your learning. Or, create a one-page sales tool and show it to ten potential customers. Define your learning and use the learning to decide what to do next.

Then what? If the first phase of the work is successful, there must be a then what. There must be an approved plan (funding, resources) for the second phase before the first phase starts. And the same thing goes for the follow-on phases. The easiest way to improve innovation effectiveness is avoid starting phase one of projects when their phase two is unfunded. The fastest innovation project is the wrong one that never starts.

How do we start? Define how much money you want to spend. Formalize your business objectives. Choose projects that could meet your business objectives. Free up your best people. Learn as quickly as you can.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

For top line growth, think no-to-yes.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Bottom line growth is good, but top line growth is better. But if you want to grow the bottom line, ignore labor costs and reduce material costs. Labor cost is only 5-10% of product cost. Stop chasing it, and, instead, teach your design community to simplify the product so it uses fewer parts and design out the highest cost elements.

Where the factory creates bottom line growth, top line growth is generated in the market/customer domain. The best way I know to grow the top line is to broaden the applicability of your products and services. But, before you can broaden applicability, you’ve got to define applicability as it is. Define the limits of what your product can do – how much it can lift, how fast it can run a calculation and where it can be used. And for your service, define who can use it, where it can be used and what elements without customer involvement. And with the limits defined, you know where top line growth won’t come from.

Radical top line growth comes only when your products and services can be used in new applications. Sure, you can train your sales force to sell more of what you already have, but that runs out of gas soon enough. But, real top line growth comes when your services serve new customers in new ways. By definition, if you’re not trying to make your product work in new ways, you’re not going to achieve meaningful top line growth. And by definition, if you’re not creating new functionality for your services, you might as well be focusing on bottom line growth.

If your product couldn’t do it and now it can, you’re doing it right. If your service couldn’t be used by people that speak Chinese and now it can, you’re on your way. If your product couldn’t be used in applications without electricity and now it can, you’re on to something. If your service couldn’t run on a smartphone and now it can, well, you get the idea.

For the acid test, think no-to-yes.

If your product can’t work in application A, you can’t sell it to people who do that work. If your service can’t be used by visually impaired people, you’re not delivering value to them and they won’t buy it. Turning can’t into can is a big deal. But you’ve got to define can’t before you can turn it into can. If you want top line growth, take the time to define the limits of applicability.

No-to-yes is powerful because it creates clarity. It’s easy to know when a project will create no-to-yes functionality and when it won’t. And that makes it easy to stop projects that don’t deliver no-to-yes value and start projects that do.

No-to-yes is the key element of a compete-with-no-one approach to business.

image credit – liebeslakritze

How to Avoid a Cliff

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

Thoughts on Selling

Like most things, selling is about people.

Like most things, selling is about people.

The hard sell has nothing to do with selling.

Just when you think you’re having the least influence, you’re having the most.

When – ready, sell, listen – has run its course, try – ready, listen, sell.

Regardless of how politely it’s asked, “How many do you want?” isn’t selling.

If sales people are compensated by sales dollars, why do you think they’ll sell strategically?

The time horizon for selling defines the selling.

When people think you’re selling, they’re not thinking about buying.

Selling is more about ears than mouths.

Selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Wanting sales people to develop relationships is a great idea; why not make it worth their while?

Solving customer problems is selling.

Making it easy to buy makes it easy to sell.

You can’t sell much without trust.

Sell like you expect your first sale will happen a year from now.

Selling is a result.

I’m not sure the best way to sell; but listening can’t hurt.

Over-promising isn’t selling, unless you only want to sell once.

Helping customers grow is selling.

Delaying gratification is exceptionally difficult, but it’s wonderful way to sell.

Ground yourself in the customers’ work and the selling will take care of itself.

People buy from people and people sell to people.

Image credit – Kevin Dooley

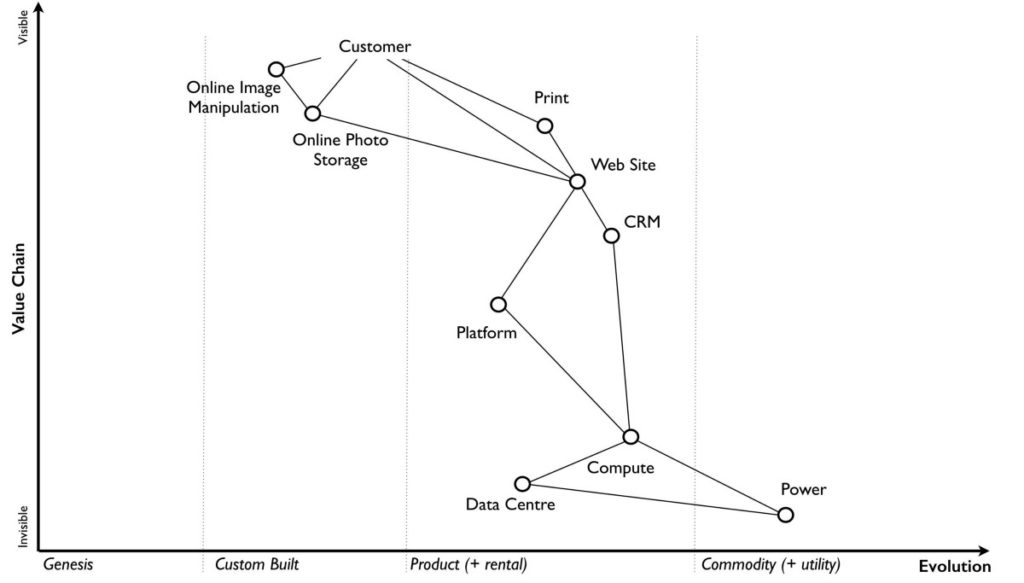

Mapping the Future with Wardley Maps

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

When there’s so many new things to work on, how do you choose the next project? When you’re lost, you look at a map. And when there is no map, you make one. The first bit of work is defined by the holes in the first revision of your map. And once the holes are filled and patched, the next work emerges from the map itself. And, in a self-similar way, the next work continually emerges from the previous work until the project finishes.

But with so much new territory, how do you choose the right new territory to map? You don’t. Before there’s a need to map new territory, you must map the current territory. What you’ll learn is there are immature areas that, when made mature, will deliver new value to customers. And you’ll also learn the mature areas that must be blown up and replaced with infant solutions that will ultimately create the next evolution of your business. And as you run thought experiments on your map – projecting advancements on the various elements – the right new territory will emerge. And here’s a hint – the right new solutions will be enabled by the newly matured elements of the map.

But how do you predict where the right new solutions will emerge? I can’t tell you that. You are the experts, not me. All I can say is, make the maps and you’ll know.

And when I say maps, I mean Wardely Maps – here’s a short video (go to 4:13 for the juicy bits).

Image credit – Simon Wardley

Too Many Balls in the Air

In today’s world of continuous improvement, everything is seen as an opportunity for improvement. The good news is things are improving. But the bad news is without governance and good judgement, things can flip from “lots of opportunity for improvement” to “nothing is good enough.” And when that happens people would rather hang their heads than stick out their necks.

In today’s world of continuous improvement, everything is seen as an opportunity for improvement. The good news is things are improving. But the bad news is without governance and good judgement, things can flip from “lots of opportunity for improvement” to “nothing is good enough.” And when that happens people would rather hang their heads than stick out their necks.

When there’s an improvement goal is propose like this “We’ve got to improve the throughput of process A by 12% over the next three months.” a company that respects their people should want (and expect) responses like these:

As you know, the team is already working to improve processes C, D, and E and we’re behind on those improvement projects. Is improvement of process A more important than the other three? If so, which project do you want to stop so we can start work on process A? If not, can we wait until we finish one of the existing projects before we start a new one? If not, why are you overloading us when we’re making it clear we already have too much work?

Are we missing customer ship dates on process A? If so, shouldn’t we move resources to process A right now to work off the backlog? If we have no extra resources, let’s authorize some overtime so we can catch up. If not, why is it okay to tolerate late shipments to our customers? Are you saying you want us to do more improvement work AND increase production without overtime?

That’s a pretty specific improvement goal. What are the top three root causes for reduced throughput? Well, if the first part of the improvement is to define the root causes, how do you know we can achieve 12% improvement in 3 months? We learned in our training that Deming said all targets are artificial. Are you trying to impose an artificial improvement target and set us up for failure?

Continuous improvement is infinitely good, but resources are finite. Like it or not, continuous improvement work WILL be bound by the resources on hand. Might as well ask for continuous improvement work in a way that’s in line with the reality of the team’s capacity.

And one thing to remember for all projects – there’s no partial credit. When you’re 80% done on ten projects, zero projects are done. It’s infinitely better to be 100% done on a single project.

Image credit – Gabriel Rojas Hruska

Allocating resources as if people and planet mattered.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

Business is about allocating resources to achieve business objectives. And for that, the best place to start is to define the business objectives.

First – what is the timeframe of the business objectives? Well, there are three – short, medium and long. Short is about making payroll, shipping this month’s orders and meeting this year’s sales objectives. Long is about the existence of the company over the next decade and happiness of the people that do the work along the way. And medium – the toughest – is in-between. It’s neither short nor long but bound by both.

Second – define business objectives within the three types: people, planet and profit.

People. Short term: pay them so they can eat, pay the mortgage and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safe workplace, give them work that fits their strengths and give them time to improve their community. Medium: pay them so they can provide for their family and fund their retirement, provide healthcare, provide a safer workplace, give them work that requires them to grow their strengths and give them time to become community leaders. Long: pay them so they can pay for their kids’ college and know they can safely retire, provide the safest workplace, let them choose their own work, and give them time to grow the next community leaders. And make it easy.

Planet. Short term: teach Life Cycle Assessment, Buddhist Economics and TRIZ and create business metrics for them to flourish. Medium: move from global sourcing to local sourcing, move to local production, move from business models based on non-renewable resources to renewable resources. Long: create new business models that are resource neutral. Longer: create business models that generate excess resources. Longest: teach others.

Profit. Short, medium and long – focus on people and planet and the profits will come. But also focus on creating new value for new customers.

For business objectives, here’s the trick on timeframe – always work short term, always work long term and prioritize medium term.

And for the three types of business objectives, focus on people, planet and creating new value for new customers. Profits are a result.

Image credit – magnetismus

Additive Manufacturing’s Holy Grail

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

The holy grail of Additive Manufacturing (AM) is high volume manufacturing. And the reason is profit. Here’s the governing equation:

(Price – Cost) x Volume = Profit

The idea is to sell products for more than the cost to make them and sell a lot of them. It’s an intoxicatingly simple proposition. And as long as you look only at the volume – the number of products sold per year – life is good. Just sell more and profits increase. But for a couple reasons, it’s not that simple. First, volume is a result. Customers buy products only when those products deliver goodness at a reasonable price. And second, volume delivers profit only when the cost is less than the price. And there’s the rub with AM.

Here’s a rule – as volume increases, the cost of AM is increasingly higher than traditional manufacturing. This is doubly bad news for AM. Not only is AM more expensive, its profit disadvantage is particularly troubling at high volumes. Here’s another rule – if you’re looking to AM to reduce the cost of a part, look elsewhere. AM is not a bottom-feeder technology.

If you want to create profits with AM, use it to increase price. Use it to develop products that do more and sell for more. The magic of AM is that it can create novel shapes that cannot be made with traditional technologies. And these novel shapes can create products with increased function that demand a higher price. For example, AM can create parts with internal features like serpentine cooling channels with fine-scale turbulators to remove more heat and enable smaller products or products that weigh less. Lighter automobiles get better fuel mileage and customers will pay more. And parts that reduce automobile weight are more valuable. And real estate under the hood is at a premium, and a smaller part creates room for other parts (more function) or frees up design space for new styling, both of which demand a higher price.

Now, back to cost. There’s one exception to cost rule. AM can reduce total product cost if it is used to eliminate high cost parts or consolidate multiple parts into a single AM part. This is difficult to do, but it can be done. But it takes some non-trivial cost analysis to make the case. And, because the technology is relatively new, there’s some aversion to adopting AM. An AM conversion can require a lot of testing and a significant cost reduction to take the risk and make the change.

To win with AM, think more function AND consolidation. More (or new) function to support a higher price (and increase volume) and reduced cost to increase profit per part. Don’t do one or the other. Do both. That’s what GE did with its AM fuel nozzle in their new aircraft engines. They combined 20 parts into a single unit which weighed 25 percent less than a traditional nozzle and was more than five times as durable. And it reduced fuel consumption (more function, higher price).

AM is well-established in prototyping and becoming more established in low-volume manufacturing. The holy grail for AM – high volume manufacturing – will become a broad reality as engineers learn how to design products to take advantage of AM’s unique ability to make previously un-makeable shapes and learn to design for radical part consolidation.

More function AND radical part consolidation. Do both.

Image credit – Les Haines

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski