Posts Tagged ‘Competitiveness’

When It’s Time to Defy Gravity

If you pull hard on your team, what will they do? Will they rebel? Will they push back? Will they disagree? Will they debate? And after all that, will they pull with you? Will the pull for three weeks straight? Will they pull with their whole selves? How do you feel about that?

If you pull hard on your team, what will they do? Will they rebel? Will they push back? Will they disagree? Will they debate? And after all that, will they pull with you? Will the pull for three weeks straight? Will they pull with their whole selves? How do you feel about that?

If you pull hard on your peers, what will they do? Will they engage? Will they even listen? Will they dismiss? And if they dismiss, will you persist? Will you pull harder? And when you pull harder, do they think more of you? And when you pull harder still, do they think even more of you? Do you know what they’ll do? And how do you feel about that?

If you push hard on your leadership, what will they do? Will they ‘lllisten or dismiss? And if they dismiss, will you push harder? When you push like hell, do they like that or do they become uncomfortable, what will you do? Will they dislike it and they become comfortable and thankful you pushed? Whatever they feel, that’s on them. Do you believe that? If not, how do you feel about that?

When you say something heretical, does your team cheer or pelt you with fruit? Do they hang their heads or do they hope you do it again? Whatever they do, they’ve watched your behavior for several years and will influence their actions.

When you openly disagree with the company line, do your peers cringe or ask why you disagree? Do they dismiss your position or do they engage in a discussion? Do they want this from you? Do they expect this from you? Do they hope you’ll disagree when you think it’s time? Whatever they do, will you persist? And how do you feel about that?

When you object to the new strategy, does your leadership listen? Or do they un-invite you to the next strategy session? And if they do, do you show up anyway? Or do they think you’re trying to sharpen the strategy? Do they think you want the best for the company? Do they know you’re objecting because everyone else in the room is afraid to? What they think of your dissent doesn’t matter. What matters is your principled behavior over the last decade.

If there’s a fire, does your team hope you’ll run toward the flames? Or, do they know you will?

If there’s a huge problem that everyone is afraid to talk about, do your peers expect you get right to the heart of it? Or, do they hope you will? Or, do they know you will?

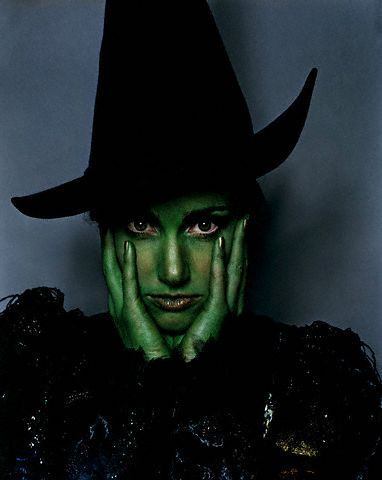

If it’s time to defy gravity, do they know you’re the person to call?

And how do you feel about that?

Image credit – The Western Sky

A Recipe to Grow Talent

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it with them, and let them hose it up. Let them do the work they know how to do, you do all the new work except for one new element, and let them do that one bit of new work. They won’t know how to do it, and they’ll get it wrong. And you’ve got to let them. Pretend you’re not paying attention so they think they’re doing it on their own, but pay deep attention. Know what they’re going to do before they do it, and protect them from catastrophic failure. Let them fail safely. And when then hose it up, explain how you’d do it differently and why you’d do it that way. Then, let them do it with your help. Praise them for taking on the new work. Praise them for trying. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help them when they need it. Let them lead the project, but stay close to the work. Pretend to be busy doing another project, but stay one step ahead of them. Know what they plan to do before they do it. If they’re on the right track, leave them alone. If they’re going to make a small mistake, let them. And be there to pick up the pieces. If they’re going to make a big mistake, casually check in with them and ask about the project. And, with a light touch, explain why this situation is different than it seems. Help them take a different approach and avoid the big mistake. Praise them for their good work. Praise them for their professionalism. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help only when they ask. Take off the training wheels and let them run the project on their own. Work on something else, and don’t keep track of their work. And when they ask for help, drop what you are doing and run to help them. Don’t walk. Run. Help them like they’re your family. Praise them for doing the work on their own. Praise them for asking for help. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do the new work for them, then repeat. Repeat the whole recipe for the next level of new work you’ll help them master.

Image credit — John Flannery

Strategy, Tactics, and Action

When it comes to strategy and tactics, there are a lot of definitions, a lot of disagreement, and a whole lot of confusion. When is it strategy? When is it tactics? Which is more important? How do they inform each other?

Instead of definitions and disagreement, I want to start with agreement. Everyone agrees that both strategy AND tactics are required. If you have one without the other, it’s just not the same. It’s like with shoes and socks: Without shoes, your feet get wet; without socks, you get blisters; and when you have both, things go a lot better. Strategy and tactics work best when they’re done together.

The objective of strategy and tactics is to help everyone take the right action. Done well, everyone from the board room to the trenches knows how to take action. In that way, here are some questions to ask to help decide if your strategy and tactics are actionable.

What will we do? This gets to the heart of it. You’ve got to be able to make a list of things that will get done. Real things. Real actions. Don’t be fooled by babble like “We will provide customer value” and “Will grow the company by X%.” Providing customer value may be a good idea, but it’s not actionable. And growing the company by an arbitrary percentage is aspirational, but not actionable.

Why will we do it? This one helps people know what’s powering the work and helps them judge whether their actions are in line with that forcing function. Here’s a powerful answer: Competitors now have products and services that are better than ours, and we can’t have that. This answer conveys the importance of the work and helps everyone put the right amount of energy into their actions. [Note: this question can be asked before the first one.]

Who will do it? Here’s a rule: if no one is freed up to do the new work, the new work won’t get done. Make a list of the teams that will stop their existing projects before they can take action on the new work. Make a list of the new positions that are in the budget to support the strategy and tactics. Make a list of the new companies you’ll partner with. Make a list of all the incremental funding that has been put in the budget to help all the new people complete all these new actions. If your lists are short or you can make any, you don’t have what it takes to get the work done. You don’t have a strategy and you don’t have tactics. You have an unfunded mandate. Run away.

When will it be done? All actions must have completion dates. The dates will be set without consideration of the work content, so they’ll be wrong. Even still, you should have them. And once you have the dates, double all the task durations and push out the dates in your mind. No need to change the schedule now (you can’t change it anyway) because it will get updated when the work doesn’t get done on time. Now, using your lists of incremental headcount and budget, assign the incremental resources to all the actions with completion dates. Look for actions and budgets as those are objective evidence of the unfunded mandate character of your strategy and tactics. And for actions without completion dates, disregard them because they can never be late.

How will we know it’s done? All actions must call out a definition of success (DOS) that defines when the action has been accomplished. Without a measurable DOS, no one is sure when they’re done so they’ll keep working until you stop them. And you don’t want that. You want them to know when they’re done so they can quickly move on to the next action without oversight. If there’s no time to create a DOS, the action isn’t all that important and neither is the completion date.

When the wheels fall off, and they will, how will we update the strategy and tactics? Strategy and tactics are forward-looking and looking forward is rife with uncertainty. You’ll be wrong. What actions will you take to see if everything is going as planned? What actions will you take when progress doesn’t meet the plan? What actions will you take when you learn your tactics aren’t working and your strategy needs a band-aid? What will you do? Who will do it? When will it be done? And how will you know it’s done?

Image credit: Eric Minbiole

What it Takes to Do New Work

What it takes to do new work.

Confidence to get it wrong and confidence to do it early and often.

Purposeful misuse of worst practices in a way that makes them the right practices.

Tolerance for not knowing what to do next and tolerance for those uncomfortable with that.

Certainty that they’ll ask for a hard completion date and certainty you won’t hit it.

Knowledge that the context is different and knowledge that everyone still wants to behave like it’s not.

Disdain for best practices.

Discomfort with success because it creates discomfort when it’s time for new work.

Certainty you’ll miss the mark and certainty you’ll laugh about it next week.

Trust in others’ bias to do what worked last time and trust that it’s a recipe for disaster.

Belief that successful business models have half-lives and belief that no one else does.

Trust that others will think nothing will come of the work and trust that they’re likely right.

Image credit — japanexpertna.se

Use less, make more.

If you use fewer natural resources, your product costs less.

If you use fewer natural resources, your product costs less.

If you use recycled materials, your product costs less.

If you use less electricity, your product costs less.

If you use less water to make your product, your product costs less.

If you use less fuel to ship your product, your product costs less.

If you make your product lighter, your product costs less.

If you use less packaging, your product costs less.

If you don’t want to be environmentally responsible because you think it’s right, at least do it to be more profitable.

Image credit — Sandrine Néel

Uncertainty Isn’t All Bad

If you think you understand what your customers want, you don’t.

If you think you understand what your customers want, you don’t.

If you’re developing a new product for new customers, you know less.

If you’re developing a new technology for a new product for new customers, you know even less.

If you think you know how much growth a new product will deliver, you don’t.

If that new product will serve new customers, you know less.

If that new product will require a new technology, you know even less.

If you have to choose between project A and B, you’ll choose the one that’s most like what you did last time.

If project A will change the game and B will grow sales by 5%, you’ll play the game you played last time.

If project A and B will serve new customers, you’ll change one of them to serve existing customers and do that one.

If you think you know how the market will respond to a new product, it won’t make much of a difference.

If you don’t know how the market will respond, you may be onto something.

If you don’t know which market the product will serve, there’s a chance to create a whole new one.

If you know how the market will respond, do something else.

When we have a choice between certainty and upside, the choice is certain.

When we choose certainty over upside, we forget that the up-starts will choose differently.

When we have a lot to lose, we chose certainty.

And once it’s lost, we start over and choose uncertainty.

Image credit — Alexandra E Rust

Will your work make the world a better place?

As parents, our lives are centered around our children and their needs. In the shortest-term, it’s all about their foundational needs like food, water, and shelter. In the medium-term, it’s all about education and person-to-person interactions. And in the longest-term, it’s all about creating the causes and conditions to help them grow into kind, caring citizens that will do the right things after we’re gone. As parents, our focus on our children gives meaning to our lives.

As parents, our lives are centered around our children and their needs. In the shortest-term, it’s all about their foundational needs like food, water, and shelter. In the medium-term, it’s all about education and person-to-person interactions. And in the longest-term, it’s all about creating the causes and conditions to help them grow into kind, caring citizens that will do the right things after we’re gone. As parents, our focus on our children gives meaning to our lives.

Though work is not the same as our children, what if we took a similar short-medium-long view to our work? And, like with our children, what if we looked at our work as a source of meaning in our lives?

Short-term, our work must pay for our food and our mortgage. And if can’t cover these expenses, the job isn’t viable. In that way, it’s easy to tell if our job works at the month-to-month timescale. You may not know if the job is right for you in the long-term, but you know if it can support your lifestyle month-to-month. And even if it’s a job we love, we know we’ve got to find another job because this one doesn’t support our family.

Medium-term, our work should pay the bills, but it should be more than that. It should allow us to be our best selves and be an avenue for continued growth and development. If you have to pretend to be someone else, you need a new job. And if you’re doing the same thing year-on-year, you need a new job. But, where it’s easy to know that your job doesn’t allow you to pay for your food and rent, it’s more difficult to acknowledge that your job isn’t right because you’ve got to wear a mask and it’s a dead-end job where next year will be the same as last year.

Long-term, our work should pay the bills, should demand we be our best selves, should demand we grow, and should make the world a better place, even after we’re gone. And where it’s difficult to acknowledge you’re in the wrong job because you must wear a mask and do what you did last year, it’s almost impossible to acknowledge you’re in the wrong job because you’re not making the world a better place.

So, I ask you now to stop for a minute and ask yourself some difficult questions. How are you making the world a better place? How are you developing yourself so you can make the world a better place?

How are you growing the future leaders that will make the world a better place?

For many reasons, it’s difficult to allocate your energy in a way that makes the world a better place. But, to me, because the world changes so slowly, the number one reason is that it’s unlikely your work will change the world in your lifetime. But, as a parent, that shouldn’t matter.

As a parent, if your work won’t change the world in your lifetime but will change the world in your children’s lifetime, that’s reason enough to do the right work. And, if your work won’t change the world in your children’s lifetime but will change it in your grandchildren’s lifetime, that is also reason enough to do the right work.

Image credit – Niall Collins

Disruption – the work that makes the best things obsolete.

I think the word “disruption” doesn’t help us do the right work. Instead, I use “innovation.” But that word has also lost much of its usefulness. There are different flavors of innovation and the flavor that maps to disruption is the flavor that makes things obsolete. This flavor of new work doesn’t improve things, it displaces them. So, when you see “innovation” in my posts, think “work that makes the best things obsolete.”

Doing work that makes the best things obsolete requires new behavior. Here’s a post that gives some tips to help make it easy for new behaviors to come to be. Within the blog post, there is a link to a short podcast that’s worth a listen. One Good Way to Change Behavior

And here’s a follow-on post about what gets in the way of new behavior. What’s in the way?

It’s difficult to define “disruption.” Instead of explaining what disruption is or isn’t, I like to use “no-to-yes.” Don’t improve the system by 3%, instead use no-to-yes to make the improved system do something the existing system cannot. Battle Success With No-to-Yes

Instead of “disruption” I like “compete with no one.” To compete with no one, you’ve got to make your services so fundamentally good that your competition doesn’t stand a chance. Compete With No One

Disruption, as a word, is not actionable. But here’s what is actionable: Choose to solve new problems. Choose to solve problems that will make today’s processes and outcomes worthless. Before you solve a problem ask yourself “Will the solution displace what we have today?” Innovation In Three Words

Here’s a nice operational definition of how to do disruption – Obsolete your best work.

And if you’re not yet out of gas, here are some posts that describe what gets in the way of new behavior and how to create the right causes and conditions for new behaviors to emerge.

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

Image credit — Thomas Wensing

Speed Through Better Decision Making

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

First things first – define the decision criteria before the work starts. That’s right – before. This is unnatural and difficult because decision criteria are typically poorly defined, if not undefined, even when the work is almost complete. Don’t believe me? Try to find the agreed-upon decision criteria for an active project. If you can find them, they’ll be ambiguous and incomplete. If you can’t find them, well, there you go.

Decision criteria aren’t just categories -like sales revenue, speed, weight – they all must have a go-no-go threshold. Sales must be greater than X, speed must be greater than Y and weight must be less than Z. A decision criterion is a category with a threshold value.

Second, before the work starts, define the actions you’ll take if the threshold values are achieved and if they are not. If sales are greater than X, speed is greater than Y and weight is less than Z, we’ll invest A dollars a year for B years to scale the business. If one of X, Y or Z are less than their threshold value, we’ll scrap the project and distribute the team throughout the organization.

Lastly, before the work starts, define the decision-maker and how their decision will be documented and communicated. In practice, there is usually just one decision-maker. So, strive to write down just one person’s name as the decision-maker. But that person will be reluctant to sign up as the decision-maker because they don’t want to be mapped the decision if things flop. Instead, the real decision-maker will put together a committee to make the decision.

To tighten things down for the committee, define how the decision will be made. Will it be a simple majority vote, a supermajority, unanimous decision or the purposefully ambiguous consensus vote. My bet is on consensus, which allows the individual committee members to distance themselves from the decision if it goes badly. And, it allows the real decision-maker to influence the consensus and effectively make the decision without making it.

Formalizing the decision process creates speed. The decision categories help the team avoid the wrong work and the threshold values eliminate the time-wasting is-it-good-enough arguments. When the follow-on actions are predefined, there’s no waiting there’s just action. And defining upfront the decision-maker and the mechanism eliminates the time-sucking ambiguity that delays decisions.

Transcending a Culture of Continuous Improvement

We’ve been too successful with continuous improvement. Year-on-year, we’ve improved productivity and costs. We’ve improved on our existing products, making them slightly better and adding features.

Our recipe for success is the same as last year plus three percent. And because the customers liked the old one, they’ll like the new one just a bit more. And the sales can sell the new one because its sold the same way as the old one. And the people that buy the new one are the same people that bought the old one.

Continuous improvement is a tried-and-true approach that has generated the profits and made us successful. And everyone knows how to do it. Start with the old one and make it a little better. Do what you did last time (and what you did the time before). The trouble is that continuous improvement runs out of gas at some point. Each year it gets harder to squeeze out a little more and each year the return on investment diminishes. And at some point, the same old improvements don’t come. And if they do, customers don’t care because the product was already better than good enough.

But a bigger problem is that the company forgets to do innovative work. Though there’s recognition it’s time to do something different, the organization doesn’t have the muscles to pull it off. At every turn, the organization will revert to what it did last time.

It’s no small feat to inject new work into a company that has been successful with continuous improvement. A company gets hooked on the predictable results of continuous which grows into an unnatural aversion to all things different.

To start turning the innovation flywheel, many things must change. To start, a team is created and separated from the continuously improving core. Metrics are changed, leadership is changed and the projects are changed. In short, the people, processes, and tools must be built to deal with the inherent uncertainty that comes with new work.

Where continuous improvement is about the predictability of improving what is, innovation is about the uncertainty of creating what is yet to be. And the best way I know to battle uncertainty is to become a learning organization. And the best way to start that journey is to create formal learning objectives.

Define what you want to learn but make sure you’re not trying to learn the same old things. Learn how to create new value for customers; learn how to deliver that value to new customers; learn how to deliver that new value in new ways (new business models.)

If you’re learning the same old things in the same old way, you’re not doing innovation.

Don’t change culture. Change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

At the highest level, you can make the biggest cultural change when you change how you spend your resources. Want to change culture? Say yes to projects that are different than last year’s and say no to the ones that rehash old themes. And to provide guidance on how to choose those new projects create, formalize new ways you want to deliver new value to new customers. When you change the criteria people use to choose projects you change the projects. And when you change the projects people’s behaviors change. And when behavior changes, culture changes.

The other important class of resources is people. When you change who runs the project, they change what work is done. And when they prioritize a different task, they prioritize different behavior of the teams. They ask for new work and get new behavior. And when those project leaders get to choose new people to do the work, they choose in a way that changes how the work is done. New project leaders change the high-level behaviors of the project and the people doing the work change the day-to-day behavior within the projects.

Change how projects are chosen and culture changes. Change who runs the projects and culture changes. Change who does the project work and culture changes.

Image credit – Eric Sonstroem

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski