Archive for the ‘Uncertainty’ Category

Transcending a Culture of Continuous Improvement

We’ve been too successful with continuous improvement. Year-on-year, we’ve improved productivity and costs. We’ve improved on our existing products, making them slightly better and adding features.

Our recipe for success is the same as last year plus three percent. And because the customers liked the old one, they’ll like the new one just a bit more. And the sales can sell the new one because its sold the same way as the old one. And the people that buy the new one are the same people that bought the old one.

Continuous improvement is a tried-and-true approach that has generated the profits and made us successful. And everyone knows how to do it. Start with the old one and make it a little better. Do what you did last time (and what you did the time before). The trouble is that continuous improvement runs out of gas at some point. Each year it gets harder to squeeze out a little more and each year the return on investment diminishes. And at some point, the same old improvements don’t come. And if they do, customers don’t care because the product was already better than good enough.

But a bigger problem is that the company forgets to do innovative work. Though there’s recognition it’s time to do something different, the organization doesn’t have the muscles to pull it off. At every turn, the organization will revert to what it did last time.

It’s no small feat to inject new work into a company that has been successful with continuous improvement. A company gets hooked on the predictable results of continuous which grows into an unnatural aversion to all things different.

To start turning the innovation flywheel, many things must change. To start, a team is created and separated from the continuously improving core. Metrics are changed, leadership is changed and the projects are changed. In short, the people, processes, and tools must be built to deal with the inherent uncertainty that comes with new work.

Where continuous improvement is about the predictability of improving what is, innovation is about the uncertainty of creating what is yet to be. And the best way I know to battle uncertainty is to become a learning organization. And the best way to start that journey is to create formal learning objectives.

Define what you want to learn but make sure you’re not trying to learn the same old things. Learn how to create new value for customers; learn how to deliver that value to new customers; learn how to deliver that new value in new ways (new business models.)

If you’re learning the same old things in the same old way, you’re not doing innovation.

What if you were gone for a month?

If you were out of the office for a month and did not check email or check in, how would things go?

If you were out of the office for a month and did not check email or check in, how would things go?

Your Team – Would your team curl up into a ball under the pressure, or would they use their judgement when things don’t go as planned? I think the answer depends on how you interacted with them over the last year. If you created an environment where it’s a genius and a thousand helpers, they won’t make any decisions because you made it clear that it’s your responsibility to make decisions and it’s their responsibility to listen. But if over the last year you demanded that they use their judgement, they’ll use it when you’re gone. Which would they do? How sure are you? And, how do you feel about that?

Other Teams – Would other teams reach out to your team for help, or would they wait until you get back to ask for help? If they wait it’s because they know you make all the decisions and your team is voice actuated – you talk and they act. But if other teams reach out directly to your team, it’s because over the last years you demonstrated to your team that you expect them to use their good judgement and make good decisions. Would other teams reach out for help or would they wait for you to get back? How do you feel about that?

Your Boss – Would your boss dive into the details of the team’s work or leave the work to the team? I think it depends on whether you were transparent with your boss over the last years about the team’s capability. If in your interactions you took credit for all the good work and blamed your team for the work that went poorly, your boss will dig into the details with your team. Your boss trusts you to do good work and not your team, and since you’re not there, your boss will think the work is in jeopardy and will set up meetings with your team to make sure the work goes well. But if over the last years you gave credit to the team and communicated the strengths and weaknesses of the team, your boss will let the team do the work. Would your boss set up the meetings or leave your team to their work? How sure are you?

To celebrate my son’s graduation from engineering school, I am taking a month off from work to ride motorcycles with him. I’m not sure how it will go with my team, the other teams and my boss, but over the last several years I’ve been getting everyone ready for just this type of thing.

Image credit — Biker Biker

Innovation isn’t uncertain, it’s unknowable.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

Where’s the Marketing Brief? In product development, the Marketing team creates a document that defines who will buy the new product (the customer), what needs are satisfied by the new product and how the customer will use the new product. And Marketing team also uses their crystal ball to estimate the number of units the customers will buy, when they’ll buy it and how much they’ll pay. In theory, the Marketing Brief is finalized before the engineers start their work.

With innovation, there can be no Marketing Brief because there are no customers, no product and no technology to underpin it. And the needs the innovation will satisfy are unknowable because customers have not asked for the them, nor can the customer understand the innovation if you showed it to them. And how the customers will use the? That’s unknowable because, again, there are no customers and no customer needs. And how many will you sell and the sales price? Again, unknowable.

Where’s the Specification? In product development, the Marketing Brief is translated into a Specification that defines what the product must do and how much it will cost. To define what the product must do, the Specification defines a set of test protocols and their measurable results. And the minimum performance is defined as a percentage improvement over the test results of the existing product.

With innovation, there can be no Specification because there are no customers, no product, no technology and no business model. In that way, there can be no known test protocols and the minimum performance criteria are unknowable.

Where’s the Schedule? In product development, the tasks are defined, their sequence is defined and their completion dates are defined. Because the work has been done before, the schedule is a lot like the last one. Everyone knows the drill because they’ve done it before.

With innovation, there can be no schedule. The first task can be defined, but the second cannot because the second depends on the outcome of the first. If the first experiment is successful, the second step builds on the first. But if the first experiment is unsuccessful, the second must start from scratch. And if the customer likes the first prototype, the next step is clear. But if they don’t, it’s back to the drawing board. And the experiments feed the customer learning and the customer learning shapes the experiments.

Innovation is different than product development. And success in product development may work against you in innovation. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to lock things down, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. If you’re doing innovation and you find yourself trying to write a specification, you may be misapplying your product development expertise. And if you are doing innovation and find yourself trying to nail down a completion date, you are definitely misapplying your product development expertise.

With innovation, people say the work is uncertain, but to me that’s not the right word. To me, the work is unknowable. The customer is unknowable because the work hasn’t been done before. The specification is unknowable because there is nothing for comparison. And the schedule in unknowable because, again, the work hasn’t been done before.

To set expectations appropriately, say the innovation work is unknowable. You’ll likely get into a heated discuss with those who want demand a Marketing Brief, Specification and Schedule, but you’ll make the point that with innovation, the rules of product development don’t apply.

Image credit — Fatih Tuluk

The Most Powerful Question

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Creativity, innovation and continuous improvement – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

And what about lifelong personal development? Yup – learning.

Learning results when a system behaves differently than your mental model. And there four ways make a system behave differently. First, give new inputs to an existing system. Second, exercise an existing system in a new way (for example, slow it down or speed it up.) Third, modify elements of the existing system. And fourth, create a new system. Simply put, if you want a system to behave differently, you’ve got to change something. But if you want to learn, the system must respond differently than you predict.

If a new system performs exactly like you expect, it isn’t a new system. You’re not trying hard enough.

When your prediction is different than how the system actually behaves, that is called error. Your mental model was wrong and now, based on the new test results, it’s less wrong. From a learning perspective, that’s progress. But when companies want predictable results delivered on a predictable timeline, error is the last thing they want. Think about how crazy that is. A company wants predictable progress but rejects the very thing that generates the learning. Without error there can be no learning.

If you don’t predict the results before you run the test, there can be no learning.

It’s exciting to create a new system and put it through its paces. But it’s not real progress – it’s just activity. The valuable part, the progress part, comes only when you have the discipline to write down what you think will happen before you run the test. It’s not glamorous, but without prediction there can be no error.

If there is no trial, there can be no error. And without error, there can be no learning.

Let’s face it, companies don’t make it easy for people to try new things. People don’t try new things because they are afraid to be judged negatively if it “doesn’t work.” But what does it mean when something doesn’t work? It means the response of the new system is different than predicted. And you know what that’s called, right? It’s called learning.

When people are afraid to try new things, they are afraid to learn.

We have a language problem that we must all work to change. When you hear, “That didn’t work.”, say “Wow, that’s great learning.” When teams are told projects must be “on time, on spec and on budget”, ask the question, “Doesn’t that mean we don’t want them to learn?”

But, the whole dynamic can change with this one simple question – “What did you learn?” At every meeting, ask “What did you learn?” At every design review, ask “What did you learn?” At every lunch, ask “What did you learn?” Any time you interact with someone you care about, find a way to ask, “What did you learn?”

And by asking this simple question, the learning will take care of itself.

Image credit m.shattock

What’s in the way?

If you want things to change, you have two options. You can incentivize change or you can move things out of the way that block change. The first way doesn’t work and the second one does. For more details, click this link at it will take you to a post that describes Danny Kahneman’s thoughts on the subject.

If you want things to change, you have two options. You can incentivize change or you can move things out of the way that block change. The first way doesn’t work and the second one does. For more details, click this link at it will take you to a post that describes Danny Kahneman’s thoughts on the subject.

And, also from Kahneman, to move things out of the way and unblock change, change the environment.

Change-blocker 1. Metrics. When you measure someone on efficiency, you get efficiency. And if people think a potential change could reduce efficiency, that change is blocked. And the same goes for all metrics associated with cost, quality and speed. When a change threatens the metric, the change will be blocked. To change the environment to eliminate the blocking, help people understand who the change will actually IMPROVE the metric. Do the analysis and educate those who would be negatively impacted if the change reduced the metric. Change their environment to one that believes the change will improve the metric.

Change-blocker 2. Incentives. When someone’s bonus could be negatively impacted by a potential change, that change will be blocked. Figure out whose incentive compensation are jeopardized by the potential change and help them understand how the potential change will actually increase their incentives. You may have to explain that their incentives will increase in the long term, but that’s an argument that holds water. Until they believe their incentives will not suffer, they’ll block the change.

Change-blocker 3. Fear. This is the big one – fear of negative consequences. Here’s a short list: fear of being judged, fear of being blamed, fear of losing status, fear of losing control, fear of losing a job, fear of losing a promotion, fear of looking stupid and fear of failing. One of the best ways to help people get over their fear is to run a small experiment that demonstrates that they have nothing to fear. Show them that the change will actually work. Show them how they’ll benefit.

Eliminating the things that block change is fundamentally different than pushing people in the direction of change. It’s different in effectiveness and approach. Start with the questions: “What’s in the way of change?” or “Who is in the way of change?” and then “Why are they in the way of change?” From there, you’ll have an idea what must be moved out of the way. And then ask: “How can their environment be changed so the change-blocker can be moved out of the way?”

What’s in the way of giving it a try?

Image credit B4bees

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

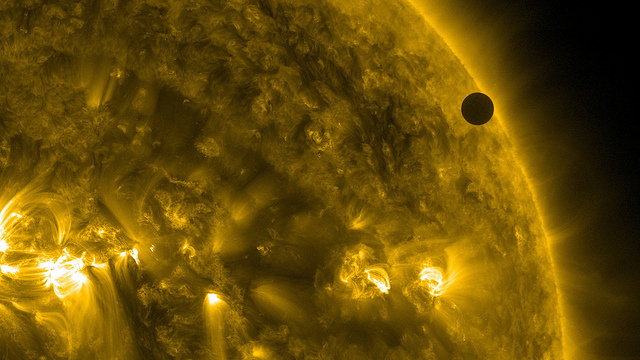

Image credit: NASA Goddard

Defy success and choose innovation.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Innovation is difficult because it requires novelty. And novelty is difficult because it’s different than last time. And different than last time is difficult because you’ve got to put yourself out there. And putting yourself out there is difficult because no one wants to be judged negatively.

Success, no matter how small, reinforces what was done last time. There’s safety in doing it again. The return may be small, but the wheels won’t fall off. You may run yourself into the ground over time, but you won’t fail catastrophically. You may not reach your growth targets, but you won’t get fired for slowly destroying the brand. In short, you won’t fail this year, but you will create the causes and conditions for a race to the bottom.

Diminishing returns are real. As a system improves it becomes more difficult to improve. A ten percent improvement is more difficult every year and at some point, improvement becomes impossible. In that way, success doesn’t breed success, it breeds more effort for less return. And as that improvement per unit effort decreases, it becomes ever more important (and ever more difficult) to do something different (to innovate).

Paradoxically, success makes it more difficult to innovate.

Success brings profits that could fund innovation. But, instead, success brings the expectation of predictable growth. Last year we were successful and grew 10%. We know the recipe, so this year let’s grow 12%. We can do what we did last year, but do it more efficiently. A sound bit of logic, except it assumes the rules haven’t changed and that competitors haven’t improved. But rules and competitors always change, and, at some point the the same old recipe for success runs out of gas.

It’s time to do something new (to innovate) when the same old effort brings reduced results. That change in output per unit effort means the recipe is tiring and it’s time for a new one. But with a new approach comes unpredictability, and for those who demand predictability, a new approach is scary. Sure, the yearly trend of reduced return on investment should scare them more, but it doesn’t. The devil you know is less scary than the one you don’t. But, it shouldn’t be.

Calculate your revenue dollars per sales associate and plot it over time. If the metric is flat over the last three years, it was time to innovate three years ago. If it’s decreasing over the last three years, it was time to innovate six years ago.

If you wait to innovate until revenue per sales person is flat, you waited too long.

No one likes to be judged negatively, more than that, no one likes their company to collapse and lose their job. So, choose to do something new (to innovate) and choose the possibility of being judged. That’s much better than choosing to go out of business.

Image credit – Michel Rathwell

The Four Ways to Run Projects

There are four ways to run projects.

There are four ways to run projects.

One – 80% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 100% On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Flex scope and certainty

Set a tight timeline and use the people and budget you have. You’ll be done on time, but you must accept a reduced scope (fewer bells and whistles) and less certainty of how the product/service will perform and how well it will be received by customers. This is a good way to go when you’re starting a new adventure or investigating new space.

Two – 100% Right, 100% Done, 0% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

- Flex time

Use the team and budget you have and tightly define the scope (features) and define the level of certainty required by your customers. Because you can’t predict when the project will be done, you’ll be late and over budget, but your offering will be right and customers will like it. Use this method when your brand is known for predictability and stability. But, be weary of business implications of being late to market.

Three – 100% Right, 100% Done, 100% On Time, 0% On Budget

- Fix scope and certainty

- Fix time

- Flex resources

Tightly define the scope and level of certainty. Your customers will get what they expect and they’ll get it on time. However, this method will be costly. If you hire contract resources, they will be expensive. And if you use internal resources, you’ll have to stop one project to start this one. The benefits from the stopped project won’t be realized and will increase the effective cost to the company. And even though time is fixed, this approach will likely be late. It will take longer than planned to move resources from one project to another and will take longer than planned to hire contract resources and get them up and running. Use this method if you’ve already established good working relationships with contract resources. Avoid this method if you have difficulty stopping existing projects to start new ones.

Four – Not Right, Not Done, Not On Time, Not On Budget

- Fix time

- Fix resources

- Fix scope and certainty

Though almost every project plan is based on this approach, it never works. Sure, it would be great if it worked, but it doesn’t, it hasn’t and it won’t. There’s not enough time to do the right work, not enough money to get the work done on time and no one is willing to flex on scope and certainty. Everyone knows it won’t work and we do it anyway. The result – a stressful project that doesn’t deliver and no one feels good about.

Image credit – Cees Schipper

Situational Awareness (Winter is Coming)

Business and life are all about choosing how you want to allocate your time and money. In life, it’s your personal time and money and in business it’s the company’s.

Business and life are all about choosing how you want to allocate your time and money. In life, it’s your personal time and money and in business it’s the company’s.

If you’ve ever done any winter hiking, you know that it’s important to know the terrain. If there’s a mountain in the way, you either go over it or around it. But there is one thing you can’t do is pretend it’s not there. If you go around it, you’ve got to make sure you have enough energy, food, water and daylight to make the long trek to shelter. If you go over it, you’ve got to make sure you have the ice picks, crampons, down jackets and climbing skills to make it up and down to shelter. With winter hiking, the territory, gear and team capability matter. And the right decision is defined by situational awareness.

And what of the shelter? Does it sleep five, six or seven? And because you have seven on your team, it’s not really shelter if it sleeps five. And if you don’t know how many it sleeps, you’re not situationally aware. And if you’re not situationally aware, on five may fit in the shelter and two will freeze to death. Maybe before your trip you should look at the map and learn all the shelters their locations and how many the can hold. The right action and the safety of your crew depends on your situational awareness.

And the decision depends on how much daylight do you have left. Before you left basecamp it was possible to know when the sun will set. Did you take the time to look at the charts? Did you take advantage of the knowledge? If you don’t have enough sunlight, you’ve got to go over the top. If you do, you can take the leisurely great circle route around the mountain. And if you don’t know, you’ve got to roll the dice. I’d prefer to be aware of the situation and keep the dice in my pocket. And for that, you need to be aware of the situation.

Winter hiking is difficult enough even when you have maps of the terrain, weather forecasts, locations of the shelters and knowledge of when the sun will set. But it’s an unsafe activity when there are no maps of the territory, the weather is unknown and there’s no knowledge of the shelters. But that’s just how it is with innovation – the territory has never been hiked, no maps, no weather forecast, and shelters are unknown. With innovation, there’s no situational awareness unless you create it. And that’s why with innovation, the first step is to create the maps. No maps, no possibility of situational awareness.

The best people at situational awareness are the military. The know maps and they know how to use them. The know to do recon to position the enemy on the map and they know to use the situational awareness (the map, the enemy’s location, and their direction of travel) to decide how what to do. If the enemy’s force is small and in poorly defensible position, there are a certain set of actions that are viable. If the enemy force is large and has the high ground, it’s time to sit tight or retreat with dignity. (To be clear, I’m a pacifist and this military example does mean I condone violence of any kind. It’s just that the military is super good at situational awareness.)

If you’re not making maps of the competitive landscape, you’re doing it wrong. If you’re not moving resources around and speculating how the competition will respond based on the topography and your position within it, you’re not sharpening your situational awareness and you’re not taking full advantage of the information around you. If you don’t know where the mountains are you can’t avoid them or use them to slow your competition. And if you don’t know know where the shelters are an how many miles you can hike in a day, you don’t know if you’re overextending your position and putting your crew at risk.

Winter is coming. If you’re not creating maps to build situational awareness, what are you doing?

Image credit – Martin Fisch

How to Avoid a Cliff

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

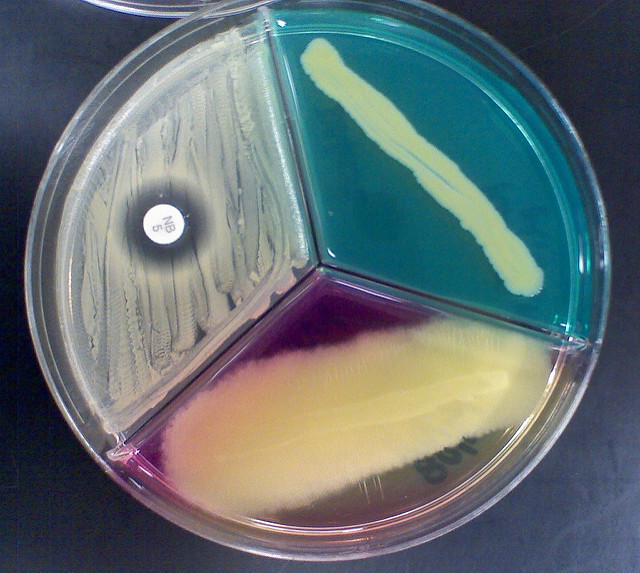

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski