Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Musings on Skillfulness

Best practices are good, but dragging projects over the finish line is better.

Best practices are good, but dragging projects over the finish line is better.

Alignment is good, but not when it’s time for misalignment.

Short-term thinking is good, as long as it’s not the only type of thinking.

Reuse of what worked last time is good, as long as it’s bolstered by the sizzle of novelty.

If you find yourself blaming the customer, don’t.

People that look like they can do the work don’t like to hang around with those that can do it.

Too much disagreement is bad, but not enough is worse.

The Status Quo is good at repeating old recipes and better at squelching new ones.

Using your judgment can be dangerous, but not using it can be disastrous.

It’s okay to have some fun, but it’s better to have more.

If it has been done before, let someone else do it.

When stuck on a tricky problem, make it worse and do the opposite.

The only thing worse than using bad judgment is using none at all.

It can be problematic to say you don’t know, but it can be catastrophic to behave as if you do.

The best way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment.

When you don’t know what to do, don’t do it.

“Old Monk” by anahitox is licensed under CC BY 2.0

What will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When people look back on your life, what will they see?

When you’re dead and gone, what stories will your kids tell about you?

What stories will your coworkers tell?

How about your bosses?

Will they see your disagreement as mischievous or skillful?

Will they see your frustration as disruptive or caring?

Will they see your vehemence as disrespectful or passionate?

Will they see your divergent views as contrarian or well-intentioned?

Will they see your withholding as passive-aggressive or as the result of exhausting all other possibilities?

Will they see your tears as sadness for yourself or the company you care about deeply?

Will they see your “no’s” as curmudgeonly given or brave?

Will they see your dissent as destructive or constructive?

Will they see your frustration as immaturity or as others falling short of your high expectations?

Will they see your unpopular perspective as troublemaking or as the antidote to groupthink?

Will they see your positivity as fake or as the support that everyone needs to do their best work?

Here’s the thing: What matters is not what it looks like from the outside, but your intentions.

And another thing: Anyone that knows you knows your intentions.

Now, go out and do what you think is right. And do it like you mean it. And don’t look back.

And here’s a mantra: What people think about you is none of your business.

What should we do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Me: It depends. How did you get here?

Anonymous: Well, we’ve had great success improving on what we did last time.

Me: Well, then you’ll likely do that again.

Anonymous: Do you think we’ll be successful this time?

Me: It depends. If the performance/goodness has been flat over your last offerings, then no. When performance has been constant over the last several offerings it means your technology is mature and it’s time for a new one. Has performance been flat over the years?

Anon: Yes, but we’ve been successful with our tried-and-true recipe and the idea of creating a new technology is risky.

Me: All things have a half-life, including successful business models and long-in-the-tooth technologies, and your success has blinded you to the fact that yours are on life support. Developing a new technology isn’t risky. What’s risk is grasping tightly to a business model that’s out of gas.

Anon: That’s harsh.

Me: I prefer “truthful.”

Anon: So, we should start from scratch and create something altogether new?

Me: Heavens no. That would be a disaster. Figure out which elements are blocking new functionality and reinvent those. Hint: look for the system elements that haven’t changed in a dog’s age and that are shared by all your competitors.

Anon: So, I only have to reinvent several elements?

Me: Yes, but probably fewer than several. Probably just one.

Anon: What if we don’t do that?

Me: Over the next five years, you’ll be successful. And then in year six, the wheels will fall off.

Anon: Are you sure?

Me: No, they could fall off sooner.

Anon: How do you know it will go down like that?

Me: I’ve studied systems and technologies for more than three decades and I’ve made a lot of mistakes. Have you heard of The Voice of Technology?

Anon: No.

Me: Well, take a bite of this – The Voice of Technology. Kevin Kelly has talked about this stuff at great length. Have you read him?

Anon: No.

Me: Here’s a beauty from Kevin – What Technology Wants. How about S-curves?

Anon: Nope.

Me: Here’s a little primer – Beyond Dead Reckoning. How about Technology Forecasting?

Anon: Hmm. I don’t think so.

Me: Here’s something from Victor Fey, my teacher. He worked with Altshuller, the creator of TRIZ – Guided Technology Evolution. I’ve used this method to predict several industry-changing technologies.

Anon: Yikes! There’s a lot here. I’m overwhelmed.

Me: That’s good! Overwhelmed is a sign you realize there’s a lot you don’t know. You could be ready to become a student of the game.

Anon: But where do I start?

Me: I’d start Wardley Maps for situation analysis and LEANSTACK to figure out if customers will pay for your new offering.

Anon: With those two I’m good to go?

Me: Hell no!

Anon: What do you mean?

Me: There’s a whole body of work to learn about. Then you’ve got to build the organization, create the right mindset, select the right projects, train on the right tools, and run the projects.

Anon: That sounds like a lot of work.

Me: Well, you can always do what you did last time. END.

“he went that way matey” by jim.gifford is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Foundation of Leadership Development — Work Products

Leadership development is a good idea in principle, but not in practice. Assessing a person against a list of seven standard competencies does not a leadership development plan make. Nor does a Meyers-Briggs assessment or a strengths assessment. The best way I know to describe the essence of leadership development is through a series of questions to assess and hire new leaders.

Leadership development is a good idea in principle, but not in practice. Assessing a person against a list of seven standard competencies does not a leadership development plan make. Nor does a Meyers-Briggs assessment or a strengths assessment. The best way I know to describe the essence of leadership development is through a series of questions to assess and hire new leaders.

Here’s the first question: Is this person capable of doing the work required for this leadership position? If you don’t start here, choose the person you like most and promote (or hire) them into the new leadership position. It’s much faster, and at least you’ll get along with them as the wheels fall off.

Next question: In this leadership position, what work products must the leader create (or facilitate the creation of)? Work products are objective evidence that the work has been completed. Examples of work products: analyses, reports, marketing briefs, spreadsheets, strategic plans, product launches, test results for new technologies. Here’s a rule: If you can’t define the required work products, you can’t define the work needed to create them. Here’s another rule: If you can’t define the work, you can’t assess a candidate’s ability to do that work. And if you can’t assess a candidate’s ability to the work, you might as well make it a popularity contest and hire the person who makes the interview committee smile.

Next question: Can the candidate show work products they’ve created that fit with those required for the leadership position? To be clear, if the candidate can show examples of all the flavors of work products required for the position, it’s a lateral move for the candidate. That’s not a bad thing, as there are good reasons candidates seek lateral positions (e.g., geographic move due to family or broadening of experience – new product line or customer segment). And if they’ve demonstrated all the work products, but the scope and/or scale are larger, the new position, the new position is a promotion for the candidate. Here’s a rule: if the candidate can’t show you an example of a specific work product or draw a picture of one on the whiteboard, they’ve never done it before. And another rule: when it comes to work products, if the candidate talks about a work product but can’t show you, it’s because they’ve never created one like that. And talking about work products in the future tense means they’ve never done it. When it comes to work products, there’s no partial credit.

Next question: For the work products the candidate has shown us, are they relevant? A candidate won’t be able to show you work products that are a 100% overlap with those required by the leadership position. The context will be different, the market will be different, and the players will be different. But, a 50-70% overlap should be good enough.

Next question: For the relevant work products the candidate has shown us, do they represent more than half of those required? If yes, go to the next question.

Next question: For the work products the candidate has not demonstrated, has the team done them? If the team has done a majority of them, that’s good. Go to the next question.

Next question: For the work products the candidate or team has not demonstrated, can we partner them with an expert (an internal one, I hope) who has? If yes, hire the candidate.

Leadership development starts with the definition of the new work the leader must be able to do in their next position. And the best way I know to define the work is to compile a collection of work products that must be created in the next position and match that against the collection of work products the leader has created. The difference between the required work products and the ones the leader has demonstrated defines the leadership development plan.

To define the leadership development plan, start with the work products.

And to help the leader develop, think apprenticeship. And for that, see this seminal report from 1945.

When is it innovation theater?

When you go to the cinema or the playhouse you go you see a show. The show may be funny, it may be sad, it may be thought-provoking, it may be beautiful, and it may take your mind off your problems for a couple of hours; but it’s not real. Sure, the storyline is good, but it came from someone’s imagination. And because it’s a story, it doesn’t have to bound by reality. Sure, the choreography is catchy, but it’s designed for effect. Yes, the cinematography paints a good picture, but it’s contrived. And, yes, the actors are good, but they’re actors. What you see isn’t real. What you see is theater.

When you go to the cinema or the playhouse you go you see a show. The show may be funny, it may be sad, it may be thought-provoking, it may be beautiful, and it may take your mind off your problems for a couple of hours; but it’s not real. Sure, the storyline is good, but it came from someone’s imagination. And because it’s a story, it doesn’t have to bound by reality. Sure, the choreography is catchy, but it’s designed for effect. Yes, the cinematography paints a good picture, but it’s contrived. And, yes, the actors are good, but they’re actors. What you see isn’t real. What you see is theater.

If you are asked to focus on the innovation process, that’s theater. Innovation doesn’t care about process; it cares about delivering novel customer value. The process isn’t most important, the output is. When there’s an extreme focus on the process that usually means an extreme focus on the output of the process would be embarrassing.

If you are tasked to calculate the net present value of the project hopper, that’s theater. With innovation, there’s no partial credit for projects you’re not working on. None. The value of the projects in the hopper is zero. The song about the value of the project hopper is nothing more than a catchy melody performed to make sure the audience doesn’t ask about the feeble collection of projects you are working on. And, assigning a value to the stagnant project hopper is a creative storyline crafted to hide the fact you have too many projects you’re not working on.

If you are asked to create high-level metrics and fancy pie charts, that’s innovation theater. Process metrics and pie charts don’t pay the bills. Here’s innovation’s script for paying the bills: complete amazing projects, launch amazing products, and sell a boatload. Full stop. If your innovation script is different than that, ball it up and throw it away along with its producer.

If the lame projects aren’t stopped so better ones can start, if people aren’t moved off stale projects onto amazing ones, if the same old teams are charged with the innovation mandate, if new leaders aren’t added, if the teams are measured just like last year, that’s innovation theater. How many mundane projects have you stopped? How many amazing projects have you started? How many new leaders have you added? How many new teams have you formed? How will you measure your teams differently? How do you feel about all that?

If a return on investment (ROI) calculation is the gating criterion before starting an amazing project, that’s innovation theater. Projects that could create a new product family with a fundamentally different value proposition for a whole new customer segment cannot be assigned an ROI because no one has experience in this new domain. Any ROI will be a guess and that’s why innovation is governed by judgment and not ROI. Innovation is unpredictable which makes an ROI is impossible to predict. And if your innovation process squeezes judgment out of the storyline, that’s a tell-tale sign of innovation theater.

If the specifications are fixed, the resources are fixed, and the completion date is fixed, that’s innovation theater. Since it can be innovation only when there’s novelty, and since novelty comes with uncertainty, without flexibility in specs, resources, or time, it’s innovation theater.

If the work doesn’t require trust, it’s innovation theater. If trust is not required it’s because the work has been done before, and if that’s the case, it’s not innovation.

If you know it will work, it’s innovation theater. Innovation and certainty cannot coexist.

If a steering team is involved, it’s innovation theater. Consensus cannot spawn innovation.

If more than one person in charge, it’s innovation theater. With innovation, there’s no place for compromise.

And what to do when you realize you’re playing a part in your company’s innovation theater? Well, I’ll save that for another time.

“Large clay theatrical mask, Romisch-Germanisches Museum, Cologne” by Following Hadrian is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Goals, goals, goals.

All goals are arbitrary, but some are more arbitrary than others.

All goals are arbitrary, but some are more arbitrary than others.

When your company treats goals like they’re not arbitrary, welcome to the US industrial complex.

What happens if you meet your year-end goals in June? Can you take off the rest of the year?

What happens if at year-end you meet only your mid-year goals? Can you retroactively declare your goals unreasonable?

What happens if at the start of the year you declare your year-end goals are unreasonable? Can you really know they’re unreasonable?

You can’t know a project’s completion date before the project is defined. That’s a rule.

Why does the strategic planning process demand due dates for projects that are yet to be defined?

The ideal future state may be ideal, but it will never be real.

When the work hasn’t been done before, you can’t know when you’ll be done.

When you don’t know when the work will be done, any due date will do.

A project’s completion date should be governed by the work content, not someone’s year-end bonus.

Resources and progress are joined at the hip. You can’t have one without the other.

If you are responsible for the work, you should be responsible for setting the completion date.

Goals are real, but they’re not really real.

“Arbitrary limitations II” by Marcin Wichary is licensed under CC BY 2.0

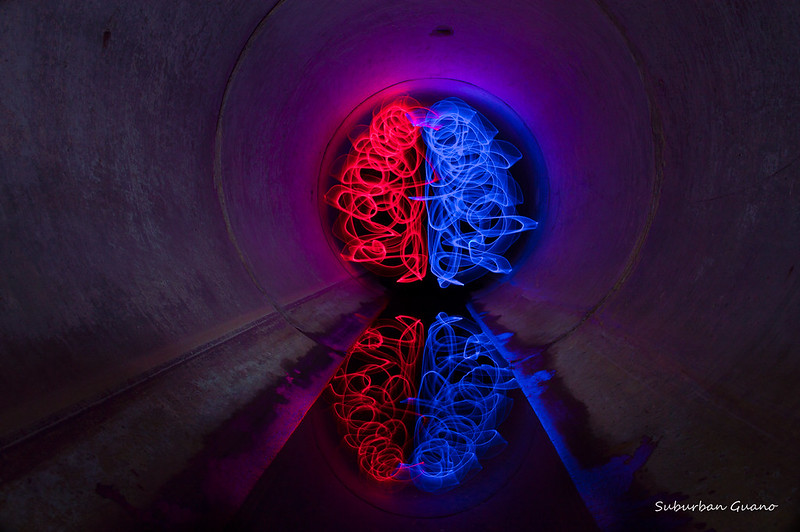

The Power of Purple

Blue isn’t better than red, and red isn’t better than blue.

Blue isn’t better than red, and red isn’t better than blue.

What’s better is wearing a red shirt with blue pants or a blue shirt with red pants.

What’s better is wearing one blue sock and one red sock.

What’s better is swapping one of your red socks for a friend’s blue one. Two matching pairs.

What’s better is offering your blue sweater to someone standing in the cold in a red tee-shirt.

What’s better is offering your red rain boots to someone standing in a puddle wearing blue sneakers.

What’s better is a blue hat with a red stripe and a red hat with a blue stripe. That’s how it starts.

What’s better is respecting the right to wear red or blue and choosing to wear purple.

What’s better is being respectful of red, respectful of blue, and coming together under a purple tent.

What’s better is thanking people for wearing purple.

What better is when blue and red are proud to wear purple.

When red and blue become purple, competition becomes cooperation.

When blue and red come together, purple carries the day.

Purple is the most powerful color, but there can be no purple without red AND blue.

“Red + Blue = Purple” by darkday. is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Do you have a problem?

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If it’s your problem, fix it. If it’s not your problem, let someone else fix it.

If you fix someone else’s problem, you prevent the organization from fixing the root cause.

If you see a problem, say something.

If you see a problem, you have an obligation to do something, but not an obligation to fix it.

If someone tries to give you their stinky problem and you don’t accept it, it’s still theirs.

If you think the problem is a symptom of a bigger problem, fixing the small problem doesn’t fix anything.

If someone isn’t solving their problem, maybe they don’t know they have a problem.

If someone you care about has a problem, help them.

If someone you don’t care about has a problem, help them, too.

If you don’t have a problem, there can be no progress.

If you make progress, you likely solved a problem.

If you create the right problem the right way, you presuppose the right solution.

If you create the right problem in the right way, the right people will have to solve it.

If you want to create a compelling solution, shine a light on a compelling problem.

If there’s a big problem but no one wants to admit it, do the work that makes it look like the car crash it is.

If you shine a light on a big problem, the owner of the problem won’t like it.

If you shine a light on a big problem, make sure you’re in a position to help the problem owner.

If you’re not willing to contribute to solving the problem, you have no right to shine a light on it.

If you can’t solve the problem, it’s because you’ve defined it poorly.

Problem definition is problem-solving.

If you don’t have a problem, there’s no problem.

And if there’s no problem, there can be no solution. And that’s a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, how can you have a solution?

If you want to create the right problem, create one that tugs on the ego.

If you want to shine a light on an ego-threatening problem, make it as compelling as a car crash – skid marks and all.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, give them an opportunity to own it, and then turn on the lights.

If shining a light on a problem will make someone look bad, so be it.

If it’s not your problem, keep your hands in your pockets or it will become your problem.

But no one can give you their problem without your consent.

If you’re damned if you do and damned if you don’t, the problem at hand isn’t your biggest problem.

If you see a problem but it’s not yours to fix, you’re not obliged to fix it, but you are obliged to shine a light on it.

When it comes to problems, when you see something, say something.

But, if shining a light on a big problem is a problem, well, you have a bigger problem.

“No Problem!” by Andy Morffew is licensed under CC BY 2.0

The truth can set you free, but only if you tell it.

Your truth is what you see. Your truth is what you think. Your truth is what feel. Your truth is what you say. Your truth is what you do.

If you see something, say something.

If no one wants to hear it, that’s on them.

If your truth differs from common believe, I want to hear it.

If your truth differs from common believe and no one wants to hear it, that’s troubling.

If you don’t speak your truth, that’s on you.

If you speak it and they dismiss it, that’s on them.

Your truth is your truth, and no one can take that away from you.

When someone tries to take your truth from you, shame on them.

Your truth is your truth. Full stop.

And even if it turns out to be misaligned with how things are, it’s still your responsibility to tell it.

If your company makes it difficult for you to speak your truth, you’re still obliged to speak it.

If your company makes it difficult for you to speak your truth, they don’t value you.

When your truth turns out to be misaligned with how things are, thank you for telling it.

You’ve provided a valuable perspective that helped us see things more clearly.

If you’re striving for your next promotion, it can be difficult to speak your dissenting truth.

If it’s difficult to speak your dissenting truth, instead of promotion, think relocation.

If you feel you must yell your dissenting truth, you’re not confident in it.

If you’re confident in your truth and you still feel you must yell it, you have a bigger problem.

When you know your truth is standing on bedrock, there’s no need to argue.

When someone argues with your bedrock truth, that’s a problem for them.

If you can put your hand over mouth and point to your truth, you have bedrock truth.

When you write a report grounded in bedrock truth, it’s the same as putting your hand over your mouth and pointing to the truth.

If you speak your truth and it doesn’t bring about the change you want, sometimes that happens.

And sometimes it brings about its opposite.

Your truth doesn’t have to be right to be useful.

But for your truth to be useful, you must be uncompromising with it.

You don’t have to know why you believe your truth; you just have to believe it.

It’s not your responsibility to make others believe your truth; it’s your responsibility to tell it.

When your truth contradicts success, expect dismissal and disbelief.

When your truth meets with dismissal and disbelief, you may be onto something.

Tomorrow’s truth will likely be different than today’s.

But you don’t have a responsibility to be consistent; you have a responsibility to the truth.

image credit — “the eyes of truth r always watching u” by TheAlieness GiselaGiardino²³ is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

It’s time to start starting.

What do we do next? I don’t know

What do we do next? I don’t know

What has been done before?

What does it do now?

What does it want to do next?

If it does that, who cares?

Why should we do it? I don’t know.

Will it increase the top line? If not, do something else.

Will it increase the bottom line? If so, let someone else do it.

What’s the business objective?

Who will buy it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

What does it look like when you know they’ll buy it?

Why do you think it’s okay to do the work before you know they’ll buy it?

What problem must be solved? I don’t know.

How will you define the problem?

Why do you think it’s okay to solve the problem before defining it?

Why do you insist on solving the wrong problem? Don’t you know that ready, fire, aim is bad for your career?

Where’s the functional coupling? When will you learn about Axiomatic Design?

Where is the problem? Between which two system elements?

When does the problem happen? Before what? During what? After what?

Will you separate in time or space?

When will you learn about TRIZ?

Who wants you to do it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

When will you read all the operating plans?

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

Who doesn’t want you to do it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

Who looks bad if this works?

Who is threatened by the work?

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

What does it look like when it’s done? I don’t know.

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

What do you need to be successful? I don’t know.

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

Starting is essential, but getting ready to start is even more so.

Image credit — Jon Marshall

Bad Behavior or Unskillful Behavior?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

What if you could see everyone as doing their best?

When they are ineffective, what if you think they are using all the skills to the best of their abilities?

What changes when you see people as having a surplus of good intentions and a shortfall of skills?

If someone cannot recognize social cues and behaves accordingly, what does that say about them?

What does it say about you if you judge them as if they recognize those social cues?

Even if their best isn’t all skillful, what if you saw them as doing their best?

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe they never learned how to behave skillfully.

When someone yells at you, maybe yelling is the only skill they were taught.

When someone treats you unskillfully, maybe that’s the only skill they have at their disposal.

And what if you saw them as doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot be stopped with punishment.

Unskillful behavior changes only when new skills are learned.

New skills are learned only when they are taught.

New skills are taught only when a teacher notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset.

And a teacher only notices a yet-to-be-developed skillset when they understand that the unskillful behavior is not about them.

And when a teacher knows the unskillful behavior is not about them, the teacher can teach.

And when teachers teach, new skills develop.

And as new skills develop, behavior becomes skillful.

It’s difficult to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as mean, selfish, uncaring, and hurtful.

It’s easier to acknowledge unskillful behavior when it’s seen as a lack of skills set on a foundation of good intentions.

When you see unskillful behavior, what if you see that behavior as someone doing their best?

Unskillful behavior cannot change unless it is called by its name.

And once called by name, skillful behavior must be clearly described within the context that makes it skillful.

If you think someone “should” know their behavior is unskillful, you won’t teach them.

And when you don’t teach them, that’s about you.

If no one teaches you to hit a baseball, you never learn the skill of hitting a baseball.

When their bat always misses the ball, would you think the lesser of them? If you did, what does that say about you?

What if no one taught you how to crochet and you were asked to knit scarf? Even if you tried your best, you couldn’t do it. How could you possibly knit a scarf without developing the skill? How would you want people to see you? Wouldn’t you like to be seen as someone with good intentions that wants to be taught how to crochet?

If you were never taught how to speak French, should I see your inability to speak French as a character defect or as a lack of skill?

We are not born with skills. We learn them.

And we cannot learn skillful behavior unless we’re taught.

When we think they “should” know better, we assume they had good teachers.

When we think their unskillful behavior is about us, that’s about us.

When we punish unskillful behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When we use prizes and rewards to change behavior, it would be more skillful to teach new skills.

When in doubt, it’s skillful to think the better of people.

Image credit — Steve Baker

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski