Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Are you striving or thriving?

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Thriving is not striving. And they’re more than unrealated. They’re opposites.

Striving is about the now and what’s in it for me. Thriving is about the greater good and choosing – choosing to choose your own path and choosing to travel it in your own way. Thriving doesn’t thrive because outcomes fit with expectations. Thriving thrives on the journey.

Where striving comes at others’ expense, thriving comes at no one’s expense. Where striving strives on getting ahead, thriving thrives on growing. Striving looks outwardly, thriving looks inwardly. No two words are spelled so similarly yet contradict so vehemently.

Plants thrive when they’re put in the right growing conditions. They grow the way they were meant to grow and they don’t look back. They thrive because they don’t second guess themselves. If they don’t grow as tall as others, they’re happy for the tallest. And if they bloom bigger and brighter than the rest, they’re thoughtful enough to make conversation about other things.

Plants and animals don’t strive. Only people do. Strivers live their lives looking through the lens of the zero sum game. Strivers feel there’s not enough sunlight to go around so they reach and stretch and step on your head so they get a tan and leave you to supplement with vitamin D.

I can deal with strivers that tell you they’re going to step on your head and step on it just as they said. And I have immense disdain for strivers that pretend they’re sunflowers. But when I’m around thrivers I resonate.

Strivers suck energy from the room and thrivers give it way freely. And just as the bumblebee gets joy from spreading the love flower-to-flower, thrivers thrive more as they give more.

If you leave a meeting feeling good about yourself and three days later you rethink things and feel like a lesser person, you were victimized by a striver. If you feel great about yourself after a meeting and three days later feel even better, you rubbed shoulders with a thriver.

Learn to spot the strivers so you can distance yourself. And seek out the thrivers so you can grow with them.

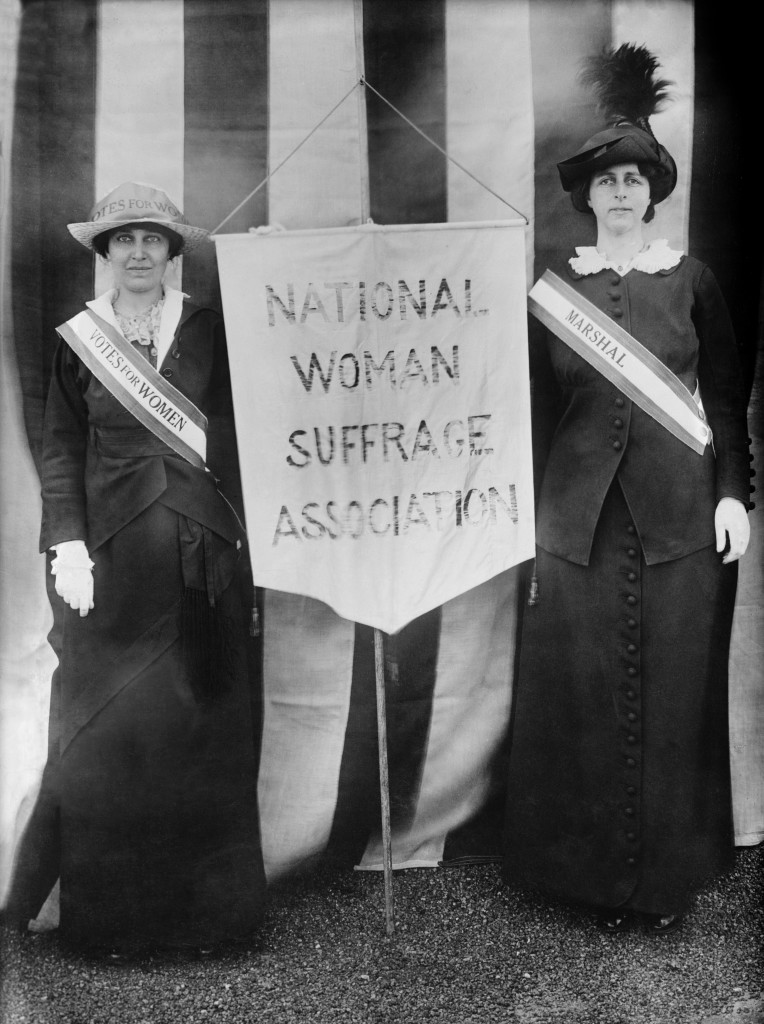

Image credit Brad Smith

If there’s no conflict, there’s no innovation.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

With Innovation, things aren’t always what they seem. And the culprit for all this confusion is how she goes about her work. Innovation starts with different, and that’s the source of all the turmoil she creates.

For the successful company, Innovation demands the company does things that are different from what made it successful. Where the company wants to do more of the same (but done better), Innovation calls it as she sees it and dismisses the behavior as continuous improvement. Innovation is a big fan of continuous improvement, but she’s a bit particular about the difference between doing things that are different and things that are the same.

The clashing of perspectives and the gnashing of teeth is not a bad thing, in fact it’s good. If Innovation simply rolls over when doing the same is rationalized as doing differently, nothing changes and the recipe for success runs out of gas. Said another way, company success is displaced by company failure. When innovation creates conflict over sameness she’s doing the company favor. Though it sometimes gives her a bad name, she’s willing to put up with the attack on her character.

The sacred business model is a mortal enemy of Innovation. Those two have been getting after each other for a long time now, and, thankfully, Innovation is willing to stand tall against the sacred business model. Innovation knows even the most sacred business models have a half-life, and she knows that she must actively dismantle them as everyone else in the company tries to keep them on life support long after they should have passed. Innovation creates things that are different (novel), useful and successful to help the company through the sad process of letting the sacred business model die with dignity. She’s willing to do the difficult work of bringing to life a younger more viral business model, knowing full well she’s creating controversy and turmoil at every turn. Innovation knows the company needs help admitting the business model is tired and old, and she’s willing to do the hard work of putting it out to pasture. She knows there’s a lot of misplaced attachment to the tired business model, but for the sake of the company, she’s willing to put it out of its misery.

For a long time now the company’s products have delivered the same old value in the same old way to the same old customers, and Innovation knows this. And because she knows that’s not sustainable, she makes a stink by creating different and more profitable value to different and more valuable customers. She uses different assumptions, different technologies and different value propositions so the company can see the same old value proposition as just that – old (and tired). Yes, she knows she’s kicking company leaders in the shins when she creates more value than they can imagine, but she’s doing it for the right reasons. Knowing full well people will talk about her behind her back, she’s willing to create the conflict needed to discredit old value proposition and adopt a new one.

Innovation is doing the company a favor when she creates strife, and the should company learn to see that strife not as disagreement and conflict for their own sake, rather as her willingness to do what it takes to help the company survive in an unknown future. Innovation has been around a long time, and she knows the ropes. Over the centuries she’s learned that the same old thing always runs out of steam. And she knows technologies and their business models are evolving faster than ever. Thankfully, she’s willing to do the difficult work of creating new technologies to fuel the future, even as the status quo attacks her character.

Without Innovation’s disruptive personality there would be far less conflict and consternation, but there’d also be far less change, far less growth and far less company longevity. Yes, innovation takes a strong hand and is sometimes too dismissive of what has been successful, but her intentions are good. Yes, her delivery is sometimes too harsh, but she’s trying to make a point and trying to help the company survive.

Keep an eye out for the turmoil and conflict that Innovation creates, and when you see it fan the flames. And when hear the calls of distress of middle managers capsized by her wake of disruption, feel good that Innovation is alive and well doing the hard work to keep the company afloat.

The time to worry is not when Innovation is creating conflict and consternation at every turn; the time to worry is when the telltale signs of her powerful work are missing.

The Top Three Enemies of Innovation – Waiting, Waiting, Waiting

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

With regard to time and resources, innovation’s biggest enemy is waiting. There. I said it.

There are books and articles that say innovation is too complex to do quickly, but complexity isn’t the culprit. It’s true there’s a lot of uncertainty with innovation, but, uncertainty isn’t the reason it takes as long as it does. Some blame an unhealthy culture for innovation’s long time constant, but that’s not exactly right. Yes, culture matters, but it matters for a very special reason. A culture intolerant of innovation causes a special type of waiting that, once eliminated, lets innovation to spool up to break-neck speeds.

Waiting? Really? Waiting is the secret? Waiting isn’t just the secret, it’s the top three secrets.

In a backward way, our incessant focus on productivity is the root cause for long wait times and, ultimately, the snail’s pace of innovation. Here’s how it goes. Innovation takes a long time so productivity and utilization are vital. (If they’re key for manufacturing productivity they must be key to innovation productivity, right?) Utilization of fixed assets – like prototype fabrication and low volume printed circuit board equipment – is monitored and maximized. The thinking goes – Let’s jam three more projects into the pipeline to get more out of our shared resources. The result is higher utilizations and skyrocketing queue times. It’s like company leaders don’t believe in queuing theory. Like with global warming, the theory is backed by data and you can’t dismiss queuing theory because it’s inconvenient.

One question: If over utilization of shared resources delays each prototype loop by two weeks (creates two weeks of incremental wait time) and you cycle through 10 prototype loops for each innovation project, how many weeks does it delay the innovation project? If you said 20 weeks you’re right, almost. It doesn’t delay just that one project; it delays all the projects that run through the shared resource by 20 weeks. Another question: How much is it worth to speed up all your innovation projects by 20 weeks?

In a second backward way, our incessant drive for productivity blinds us of the negative consequences of waiting. A prototype is created to determine viability of a new technology, and this learning is on the project’s critical path. (When the queue time delays the prototype loop by two weeks, the entire project slips two weeks.) Instead of working to reduce the cycle time of the prototype loop and advance the critical path, our productivity bias makes us work on non-critical path tasks to fill the time. It would be better to stop work altogether and help the company feel the pain of the unnecessarily bloated queue times, but we fill the time with non-critical path work to look busy. The result is activity without progress, and blindness to the reason for the schedule slip – waiting for the over utilized shared resource.

A company culture intolerant of uncertainty causes the third and most destructive flavor of waiting. Where productivity and over utilization reduce the speed of innovation, a culture intolerant of uncertainty stops innovation before it starts. The culture radiates negative energy throughout the labs and blocks all experiments where the results are uncertain. Blocking these experiments blocks the game-changing learning that comes with them, and, in that way, the culture create infinite wait time for the learning needed for innovation. If you don’t start innovation you can never finish. And if you fix this one, you can start.

To reduce wait time, it’s important to treat manufacturing and innovation differently. With manufacturing think efficiency and machine utilization, but with innovation think effectiveness and response time. With manufacturing it’s about following an established recipe in the most productive way; with innovation it’s about creating the new recipe. And that’s a big difference.

If you can learn to see waiting as the enemy of innovation, you can create a sustainable advantage and a sustainable company. It’s time to change expectations around waiting.

Image credit – Pulpolux !!!

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Innovation is alive and well.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself; rather, it’s a result of something. Set the right input conditions, monitor the right things in the right ways, and innovation weaves itself into the genetic makeup of your company. Like ivy, it grabs onto outcroppings that are the heretics and wedges itself into the cracks of the organization. It grows unpredictably, it grows unevenly, it grows slowly. And one day you wake up and your building is covered with the stuff.

Ivy doesn’t grow by mistake – It takes some initial plantings in strategic locations, some water, some sun, something to attach to, a green thumb and patience. Innovation is the same way.

There’s no way to predict how ivy will grow. One young plant may dominate the others; one trunk may have more spurs and spread broadly; some tangles will twist on each other and spiral off in unforeseen directions; some vines will go nowhere. Though you don’t know exactly how it will turn out, you know it will be beautiful when the ivy works its evolutionary magic. And it’s the same with innovation.

Ivy and innovation are more similar than it seems, and here are some rules that work for both:

- If you don’t plant anything, nothing grows.

- If growing conditions aren’t right, nothing good comes of it.

- Without worthy scaffolding, it will be slow going.

- The best time to plant the seeds was three years ago.

- The second best time to plant is today.

- If you expect predictability and certainty, you’ll be frustrated.

Innovation is the output of a set of biological systems – our people systems – and that’s why it’s helpful to think of innovation as if it’s alive because, well, it is. And like with a thriving colony of ants that grows steadily year-on-year, these living systems work well. From 10,000 foot perspective ants and innovation look the same – lots of chaotic scurrying, carrying and digging. And from an ant-to-ant, innovator-to-innovator perspective they are the same – individuals working as a coordinated collective within a shared mindset of long term sustainability.

Image credit – Cindy Cornett Seigle

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

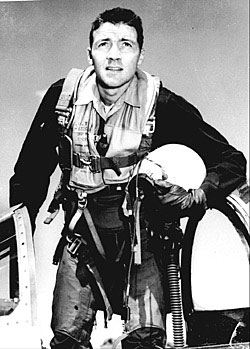

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

Clarity is King

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

There’s a strong desire to claim there’s a ton of projects happening all at once, but projects aren’t like that. Projects happen serially. Start one, finish one is the best way. Sure it’s sexy to talk about doing projects in parallel, but when the rubber meets the road, it’s “one at time” until you’re done.

The thing to remember about projects is there’s no partial credit. If a project is half done, the realized value is zero, and if a project is 95% done, the realized value is still zero (but a bit more frustrating). But to rationalize that we’ve been working hard and that should count for something, we allocate partial credit where credit isn’t due. This binary thinking may be cold, but it’s on-the-mark. If your new product is 90% done, you can’t sell it – there is no realized value. Right up until it’s launched it’s work in process inventory that has a short shelf like – kind of like ripe tomatoes you can’t sell. If your competitor launches a winner, your yet-to-see-day light product over-ripens.

Get a pencil and paper and make the list of the active projects that are fully staffed, the ones that, come hell or high water, you’re going to deliver. Short list, isn’t it? Those are the projects you track and report on regularly. That’s clarity. And don’t talk about the project you’re not yet working on because that’s clarity, too.

Are those the right projects? You can slice them, categorize them, and estimate the profits, but with such a short list, you don’t need to. Because there are only a few active projects, all you have to do is look at the list and decide if they fit with company expectations. If you have the right projects, it will be clear. If you don’t, that will be clear as well. Nothing fancy – a list of projects and a decision if the list is good enough. Clarity.

How will you know when the projects are done? That’s easy – when the resources start work on the next project. Usually we think the project ends when the product launches, but that’s not how projects are. After the launch there’s a huge amount of work to finish the stuff that wasn’t done and to fix the stuff that was done wrong. For some reason, we don’t want to admit that, so we hide it. For clarity’s sake, the project doesn’t end until the resources start full-time work on the next project.

How will you know if the project was successful? Before the project starts, define the launch date and using that launch data, set a monthly profit target. Don’t use units sold, units shipped, or some other anti-clarity metric, use profit. And profit is defined by the amount of money received from the customer minus the cost to make the product. If the project launches late, the profit targets don’t move with it. And if the customer doesn’t pay, there’s no profit. The money is in the bank, or it isn’t. Clarity.

Clarity is good for everyone, but we don’t behave that way. For some reason, we want to claim we’re doing more work than we actually are which results in mis-set expectations. We all know it’s matter of time before the truth comes out, so why not be clear? With clarity from the start, company leaders will be upset sooner rather than later and will have enough time to remedy the situation.

Be clear with yourself that you’re highly capable and that you know your work better than anyone. And be clear with others about what you’re working on and what you’re not. Be clear about your test results and the problems you know about (and acknowledge there are likely some you don’t know about).

I think it all comes down to confidence and self-worth. Have the courage wear clarity like a badge of honor. You and your work are worth it.

Image credit – Greg Foster

Innovation Fortune Cookies

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long.

Whether you like it or not, when you start something new uncertainty carries the day.

Don’t define the idealized future state, advance the current state along its lines of evolutionary potential.

Try new things then do more of what worked and less of what didn’t.

Without starting, you never start. Starting is the most important part

Perfection is the enemy of progress, so are experts.

Disruption is the domain of the ignorant and the scared.

Innovation is 90% people and the other half technology.

The best training solves a tough problem with new tools and processes, and the training comes along for the ride.

The only thing slower than going too slowly is going too quickly.

An innovation best practice – have no best practices.

Decisions are always made with judgment, even the good ones.

image credit – Gwen Harlow

Top Innovation Blogger of 2014

Innovation Excellence announced their top innovation bloggers of 2014, and, well, I topped the list!

Innovation Excellence announced their top innovation bloggers of 2014, and, well, I topped the list!

The list is full of talented, innovative thinkers, and I’m proud to be part of such a wonderful group. I’ve read many of their posts and learned a lot. My special congratulations and thanks to: Jeffrey Baumgartner, Ralph Ohr, Paul Hobcraft, Gijs van Wulfen, and Tim Kastelle.

Honors and accolades are good, and should be celebrated. As Rick Hanson knows (Hardwiring Happiness) positive experiences are far less sticky than negative ones, and to be converted into neural structure must be actively savored. Today I celebrate.

Writing a blog post every week is challenge, but it’s worth it. Each week I get to stare at a blank screen and create something from nothing, and each week I’m reminded that it’s difficult. But more importantly I’m reminded that the most important thing is to try. Each week I demonstrate to myself that I can push through my self-generated resistance. Some posts are better than others, but that’s not the point. The point is it’s important to put myself out there.

With innovative work, there are a lot of highs and lows. Celebrating and savoring the highs is important, as long as I remember the lows will come, and though there’s a lot of uncertainty in innovation, I’m certain the lows will find me. And when that happens I want to be ready – ready to let go of the things that don’t go as expected. I expect thinks will go differently than I expect, and that seems to work pretty well.

I think with innovation, the middle way is best – not too high, not too low. But I’m not talking about moderating the goodness of my experiments; I’m talking about moderating my response to them. When things go better than my expectations, I actively hold onto my good feelings until they wane on their own. When things go poorly relative to my expectations, I feel sad for a bit, then let it go. Funny thing is – it’s all relative to my expectations.

I did not expect to be the number one innovation blogger, but that’s how it went. (And I’m thankful.) I don’t expect to be at the top of the list next year, but we’ll see how it goes.

For next year my expectations are to write every week and put my best into every post. We’ll see how it goes.

To improve innovation, improve clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

For clarity on the innovative new product, here’s what the CEO needs.

Valuable Customer Outcomes – how the new product will be used. This is done with a one page, hand sketched document that shows the user using the new product in the new way. The tool of choice is a fat black permanent marker on an 81/2 x 11 sheet of paper in landscape orientation. The fat marker prohibits all but essential details and promotes clarity. The new features/functions/finish are sketched with a fat red marker. If it’s red, it’s new; and if you can’t sketch it, you don’t have it. That’s clarity.

The new value proposition – how the product will be sold. The marketing leader creates a one page sales sheet. If it can’t be sold with one page, there’s nothing worth selling. And if it can’t be drawn, there’s nothing there.

Customer classification – who will buy and use the new product. Using a two column table on a single page, these are their attributes to define: Where the customer calls home; their ability to pay; minimum performance threshold; infrastructure gaps; literacy/capability; sustainability concerns; regulatory concerns; culture/tastes.

Market classification – how will it fit in the market. Using a four column table on a single page, define: At Whose Expense (AWE) your success will come; why they’ll be angry; what the customer will throw way, recycle or replace; market classification – market share, grow the market, disrupt a market, create a new market.

For clarity on the creative work, here’s what the CEO needs: For each novel concept generated by the Innovation Burst Event (IBE), a single PowerPoint slide with a picture of its thinking prototype and a word description (limited to 12 words).

For clarity on the problems to be solved the CEO needs a one page, image-based definition of the problem, where the problem is shown to occur between only two elements, where the problem’s spacial location is defined, along with when the problem occurs.

For clarity on the viability of the new technology, the CEO needs to see performance data for the functional prototypes, with each performance parameter expressed as a bar graph on a single page along with a hyperlink to the robustness surrogate (test rig), test protocol, and images of the tested hardware.

For clarity on commercialization, the CEO should see the project in three phases – a front, a middle, and end. The front is defined by a one page project timeline, one page sales sheet, and one page sales goals. The middle is defined by performance data (bar graphs) for the alpha units which are hyperlinked to test protocols and tested hardware. For the end it’s the same as the middle, except for beta units, and includes process capability data and capacity readiness.

It’s not easy to put things on one page, but when it’s done well clarity skyrockets. And with improved clarity the right concepts are created, the right problems are solved, the right data is generated, and the right new product is launched.

And when clarity extends all the way to the CEO, resources are aligned, organizational confusion dissipates, and all elements of innovation work happen more smoothly.

Image credit – Kristina Alexanderson

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski