Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

Thoughts on Selling

Like most things, selling is about people.

Like most things, selling is about people.

The hard sell has nothing to do with selling.

Just when you think you’re having the least influence, you’re having the most.

When – ready, sell, listen – has run its course, try – ready, listen, sell.

Regardless of how politely it’s asked, “How many do you want?” isn’t selling.

If sales people are compensated by sales dollars, why do you think they’ll sell strategically?

The time horizon for selling defines the selling.

When people think you’re selling, they’re not thinking about buying.

Selling is more about ears than mouths.

Selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Wanting sales people to develop relationships is a great idea; why not make it worth their while?

Solving customer problems is selling.

Making it easy to buy makes it easy to sell.

You can’t sell much without trust.

Sell like you expect your first sale will happen a year from now.

Selling is a result.

I’m not sure the best way to sell; but listening can’t hurt.

Over-promising isn’t selling, unless you only want to sell once.

Helping customers grow is selling.

Delaying gratification is exceptionally difficult, but it’s wonderful way to sell.

Ground yourself in the customers’ work and the selling will take care of itself.

People buy from people and people sell to people.

Image credit – Kevin Dooley

Don’t trust your gut, run the test.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

At first glance, it seems easy to run a good test, but nothing can be further from the truth.

The first step is to define the idea/concept you want to validate or invalidate. The best way is to complete one of these two sentences: I want to learn that [type your idea here] is true. Or, I want to learn that [enter your idea here] is false.

Next, ask yourself this question: What information do I need to validate (or invalidate) [type your idea here]? Write down the information you need. In the engineering domain, this is straightforward: I need the temperature of this, the pressure of that, the force generated on part xyz or the time (in seconds) before the system catches fire. But for people-related ideas, things aren’t so straightforward. Some things you may want to know are: how much will you pay for this new thing, how many will you buy, on a scale of 1 to 5 how much do you like it?

Now the tough part – how will you judge pass or fail? What is the maximum acceptable temperature? What is the minimum pressure? What is the maximum force that can be tolerated? How many seconds must the system survive before catching fire? And for people: What is the minimum price that can support a viable business? How many must they buy before the company can prosper? And if they like it at level 3, it’s a go. And here’s the most importance sentence of the entire post:

The decision criteria must be defined BEFORE running the test.

If you wait to define the go/no-go criteria until after you run the test and review the data, you’ll adjust the decision criteria so you make the decision you wanted to make before running the test. If you’re not going to define the decision criteria before running the test, don’t bother running the test and follow your gut. Your decision will be a bad one, but at least you’ll save the time and money associated with the test.

And before running the test, define the test protocol. Think recipe in a cookbook: a pinch of this, a quart of that, mix it together and bake at 350 degrees Fahrenheit for 40 minutes. The best protocols are simple and clear and result in the same sequence of events regardless of who runs the test. And make sure the measurement method is part of the protocol – use this thermocouple, use that pressure gauge, use the script to ask the questions about price and the number they’d buy.

And even with all this rigor, good judgement is still part of the equation. But the judgment is limited to questions like: did we follow the protocol? Did the measurement system function properly? Do the initial assumptions still hold? Did anything change since we defined the learning objective and defined the test protocol?

To create formal learning objectives, to write well-defined test protocols and to formalize the decision criteria before running the test require rigor, discipline, time and money. But, because the cost of making a bad decision is so high, the cost of running good tests is a bargain at twice the price.

Image credit – NASA Goddard Flight Center

Starting 101

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

The downside of making a mistake is far less than the downside of not starting.

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long to start.

Stopping is fine, as long as it’s followed closely by starting.

The scope of the project you start is defined by the cash in your pocket.

If you don’t start you can’t learn.

The project doesn’t have to be all figured out before starting, you just have to start.

Starting is scary because it’s important.

Before you can start you’ve got to decide to start.

If you’re finally ready to start, you should have started yesterday.

Without starting there can be no finishing.

Starting is blocked by both the fear of success and the fear of failure.

You don’t need to be ready to start, you just need to start.

The only thing in the way of starting is you.

Image credit — Dermot O’Halloran

A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

A three-pronged approach for making progress

When you’re looking to make progress, the single most important skill is to see waiting as waiting.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you queue up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. When these meetings spring up, it’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

Another place to look for waiting is the process to schedule a meeting with high-level leaders. Their schedules are so full (efficiency over effectiveness) the next open meeting slot is next month. Let me translate – “As a senior leader and decision maker, I want you to delay the business-critical project until I carve out an hour so you can get me up to speed and I can tell you what to do.” The best project managers don’t wait. They schedule the meeting three weeks from now, make progress like their hair is on fire and provide a status update when the meeting finally happens. And the smartest leaders thank the project managers for using their discretion and good judgment.

A variant of the wait-for-the-most-important-leader theme is the never-ending-series-of-meetings-where-no-decisions-are-made scenario. The classic example of this unhealthy lifestyle is where a meeting to make a decision spawns a never-ending series of weekly meetings with 12 or more regular attendees where the initial agenda of making a decision death spirals into an ever-changing, and ultimately disappearing agenda. Everyone keeps meeting, but no one remembers why. And the decision is never made. The saddest part is that no one remembers that project is blocked by the non-decision.

The first place to look for waiting is the queue in front of a shared resource. Like taking a number at the deli, you line up behind the work that got there first and your work waits its turn. And when the situation turns bad, prioritization meeting spring up to argue about the importance of one bit of work over another. Those meetings are a sure-fire sign of ineffectiveness. It’s time to increase capacity of the shared resource to stop waiting and start making progress.

And the deadliest waiting is the waiting that we no longer see as waiting. The best example of this crippling non-waiting waiting is when we cannot work the critical path and, instead, we work on a task of secondary importance. We kid ourselves into thinking we’re improving efficiency when, in fact, we’re masking the waiting and enabling the poor decision making that starved the project of the resources it needs to work the critical path. Whether you work a non-critical path task or not, when you can’t work the critical path for a week, you delay project completion by a week. That’s a rule.

Instead of spending energy working a non-critical path task, it’s better for everyone if you do nothing. Sit at your desk and play solitaire on your computer or surf the web. Do whatever it takes for your leader to recognize you’re not making progress. And when your leader tries to chastise you, tell them to do their job and give you what you need to work the critical path.

There’s two types of work – value-added work and non-value-added work. Value-added work happens when you complete a task on the critical path. Non-value-added work happens when you wait, when you do work that’s not on the critical path, when you get ready to do work and when you clean up after doing work. In most processes, the ratio of non-value-added to value-added work is 20:1 to 200:1. Meaning, for every hour of value-added work there are twenty to two hundred hours of non-value-added work.

If you want to make progress, don’t improve how you do your value-added work. Instead, identify the non-value-added work you can stop and stop it. In that way, without changing how you do an hour long value-added task, you can eliminate twenty to two hundred hours wasted effort.

Here’s the three-pronged approach for making progress:

Prong one – eliminate waiting. Prong two – eliminate waiting. Prong three – eliminate waiting.

Image credit João Lavinha

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

The Power of Surprise

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

There’s disagreement on what is creative, innovative and disruptive. And there is no set of hard criteria to sort concepts into the three categories. Stepping back a bit, a lesser but still important sorting is an in-or-out categorization. Though not as good as discerning among the three, it is useful to decide if a new concept is in (one of the three) or out (not).

The closest thing to an acid test is assessment of the emotional response generated by a new concept. Here are some responses that I consider tell-tail signs of powerful ideas/concepts worthy of the descriptors creative, innovative, or disruptive.

When first shown, a prototype creates fear and defensiveness. The fear signals that the prototype threatens the status quo and defensiveness is objective evidence of the fear.

When first explained, a new concept creates anger and aggression. Because the concept doesn’t play by the rules, it disrespects everything holy, and the unfairness spawns indigence.

After some time, the dismissive comments about the new prototype fade and turn to discussions colored by deep sadness as the gravity of the situation hits home.

But the best leading indicator is surprise. When a test result doesn’t match your expectations, it generates surprise. And since your expectations are built on your mental models, surprising concepts contradict your mental models. And since your mental models are formed by successful experiences, prototypes that create surprise violate previous success.

If you’re surprised by a new concept, it’s worth a deeper look. If you’re not surprised, move on.

If you’re not tolerant of surprise, you should be. And if you are tolerant of surprise, it’s time to become fervent.

Image credit – Raul Pop

The one good way to change behavior.

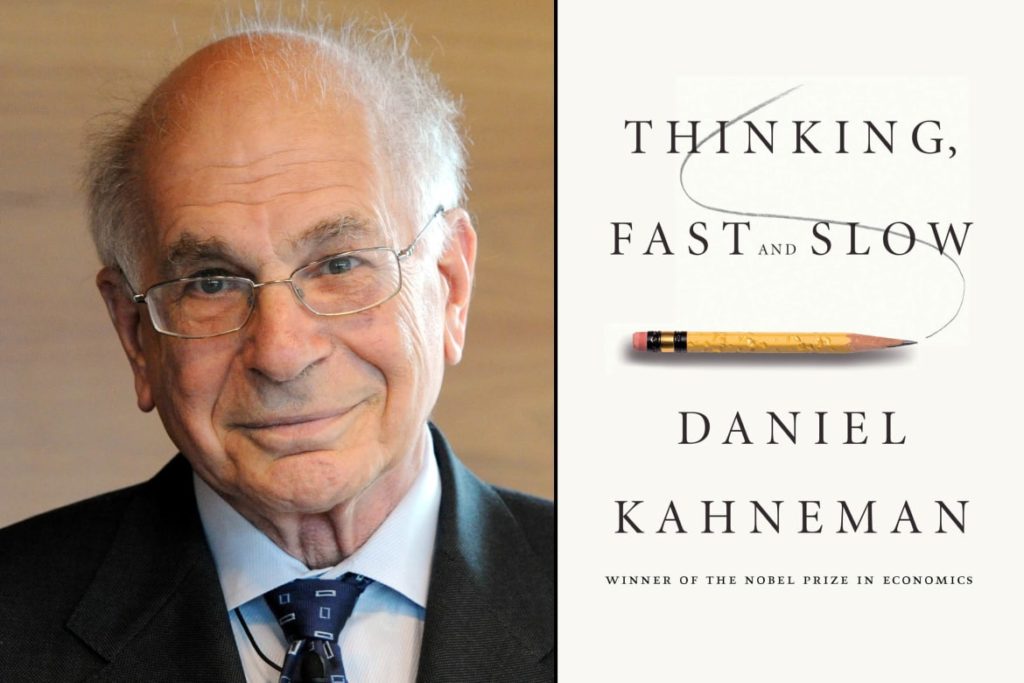

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

There’s one good way to change behavior. But don’t take my word for it, take Daniel Kahneman’s, psychologist who was awarded the Nobel Prize in Economic Sciences. In Freakonomics Radio’s podcast How to Launch a Behavioral Change Revolution, Kahneman explains how to achieve change in behavior. His explanation is short [30:35 – 35:21] and good.

Kahneman describes a theory of Kurt Lewin, his academic grandfather, where behavior is an equilibrium, a balance between driving forces that push for change and restraining forces that hold back change. Kahneman goes on to describe Lewin’s insight. “Lewin’s insight was that if you want to achieve change in behavior, there is one good way to do it and one bad way. The good way is by diminishing restraining forces, not by increasing the driving forces. That turns out to be profoundly non-intuitive.”

Usually, when we want someone to change, we push them in the direction we want them to go. Kahneman says this approach is natural, but ineffective. He offers a different approach – “Instead of asking how can I get him or her to do it, it starts with a question of why isn’t she doing it already? Go one-by-one, systematically, and you ask ‘What can I do to make it easier for that person to move?’”

What would happen if instead of pushing someone to change, you understand what’s in the way and eliminated the restraining force? I don’t know, but I’m going to give it a try.

Kahneman goes on to describe how to make things easier for a person to move. He says “…the way to make things easier is almost always by controlling the individual’s environment…by just making it easier.” Sounds pretty simple – change people’s environment to make it easier for them to move toward the desired behavior. But, we don’t do it that way.

Kahneman gives more detail. “Are there incentives that work against it? Let’s change the incentives.” And then he gives a simple example. “I want to influence B, but there is A in the background and it’s A who is a restraining force on B, let’s work on A, not on B.”

I urge you to listen to the short segment to hear Kahneman’s words for yourself. His ideas really hit home when you hear them from him.

Leadership isn’t binary, and that’s why judgement is important.

100% of the people won’t like your new idea, even if it’s a really good one like the airplane, mayonnaise or air conditioning.

100% of the people won’t like your new idea, even if it’s a really good one like the airplane, mayonnaise or air conditioning.

I don’t know the right amount of conflict, but I know it’s not 0% or 100%.

If 100% is good, 110% isn’t better. Percentages don’t work that way.

100% alignment is not the best thing. Great things aren’t built on the back of consensus.

100% of the problems shouldn’t be solved. Sometimes it’s best to let the problem blossom into something that cannot be dismissed, denied or avoided.

Fitting in can be good, but not 100% of the time. Sometimes the people in power need to hear the truth, even if you know they’ll choke on it.

If the system is in the way, work the rule. Follow it 100%, follow it to the letter, follow it until it’s absurd. But, keep in mind the system isn’t in the way 100% of the time.

Following the process 100% eliminates intellectual diversity. And, as Darwin said, that leads to extinction. I think he was onto something.

Trying to fix 100% of the problems leads to dilution. Solve one at a time until you’re done.

The best tool isn’t best 100% of the time. Here’s a rule: If the work’s new, try a new tool. You can’t cut a board with a hammer.

I don’t know how frequently to make mistakes, but I know it’s not 0% or 100% of the time.

As a sport, leadership isn’t binary. That’s why we’re paid to use our good judgement.

Image credit – Joe Dyer

Wisdom Within Dichotomy

To create future success, you’ve got to outlaw the very thing responsible for your past success.

To create future success, you’ve got to outlaw the very thing responsible for your past success.

Sometimes slower is faster and sometimes slower is slower. But it’s always a judgement call.

We bite the bullet and run expensive experiments because they’re valuable, but we neglect to run the least expensive thought experiments because they’re too disruptive.

There’s an infinite difference between the impossible and the almost impossible. And the people that can tell the difference are infinitely important.

If you know how to do it, so does your competition. Do something else.

We want differentiation, but we can’t let go of the sameness of success.

People that make serious progress take themselves lightly.

If you can predict when the project will finish, you can also predict customers won’t be excited when you do.

If you don’t have time to work on something, you can still work on it a little a time.

Perfection is good, but starting is better.

Sometimes it’s time to think and sometimes it’s time to do. And it’s easy to decide because doing starts with thinking.

When your plate is full and someone slops on a new project, there may be a new project on your plate but there’s also another project newly flopped on the floor.

New leaders demand activity and seasoned professionals make progress.

Sometimes it’s not ready, but most of the time it’s ready enough.

There’s no partial credit for almost done. That’s why pros don’t start a project until they finish one.

In this age of efficiency, effectiveness is far more important.

Image credit — Silentmind8

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski