Archive for the ‘Seeing Things As They Are’ Category

Making a difference starts with recognizing the opportunity to make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

When you’re in a meeting, watch and listen. If someone is quiet, ask them a question. My favorite is “What do you think?” Your question says you value them and their thinking, and that makes a difference. Others will recognize the difference you made, and that may inspire them to make a similar difference at their next meeting.

When you see a friend in the hallway, look them in the eyes, smile, and ask them what they’re up to. Listen to their words but more importantly watch their body language. If you recognize they are energetic, acknowledge their energy, ask what’s fueling them, and listen. Ask more questions to let them know you care. That will make a difference. If you recognize they have low energy, tell them, and then ask what that’s all about. Try to understand what’s going on for them. You don’t have to fix anything to make a difference, you have to invest in the conversation. They’ll recognize your genuine interest and that will make a difference.

If you remember someone is going through something, send them a simple text – “I’m thinking of you.” That’s it. Just say that. They’ll know you remembered their situation and that you care. And that will make a difference. Again, you don’t have to fix anything. You just have to send the text.

Check in with a friend. That will make a difference.

When you learn someone got a promotion, send them a quick note. Sooner is better, but either way, you’ll make a difference.

Ask someone if they need help. Even if they say no, you’ve made a difference. And if they say yes, help them. That will make a big difference.

And here’s a little different spin. If you need help, ask for it. Tell them why you need it and explain why you asked them. You’ll demonstrate vulnerability and they’ll recognize you trust them. Difference made. And your request for help will signal that you think they’re capable and caring. Another difference made.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference. Pay attention and take action and you’ll make a difference. But really, you’ll make two differences. You’ll make a difference for them and you’ll make a difference for yourself.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Give your sales team a reason to talk to customers. Create something that your salespeople can talk about with customers. A mildly modified product offering, a new bundling of existing products, a brochure for an upcoming new product, a price reduction, a program to keep prices as they are even though tariffs are hitting you. Give them a chance to talk about something new so the customers can buy something (old or new).

Think Least Launchable Unit (LLU). Instead of a platform launch that can take years to develop and commercialize, go the other way. What’s the minimum novelty you can launch? What will take the least work to launch the smallest chunk of new value? Whatever that is, launch it now.

Take a Frankensteinian approach. Frankenstein’s monster was a mix and match of what the good doctor had scattered about his lab. The head was too big, but it was the head he had. And he stitched onto the neck most crudely with the tools he had at his disposal. The head was too big, but no one could argue that the monster didn’t have a head. And, yes, the stitching was ugly, but the head remained firmly attached to the neck. Not many were fans of the monster, but everyone knew he was novel. And he was certainly something a sales team could talk about with customers. How can you combine the head from product A with the body of product B? How can you quickly stitch them together and sell your new monster?

Less-With-Far-Less. You’ve already exhausted the more-with-more design space. And there’s no time for the technical work to add more. It’s time for less. Pull out some functionality and lots of cost. Make your machines do less and reduce the price. Simplify your offering and make things easier for your customers. Removing, eliminating, and simplifying usually comes with little technical risk. Turning things down is far easier than turning them up. You’ll be pleasantly surprised how excited your customers will be when you offer them slightly less functionality for far less money.

These are trying times, but they’re not to be wasted. The pressure we’re all under can open us up to do new work in new ways. Push the envelope. Propose new offerings that are inelegant but take advantage of the new sense of urgency forced.

Be bold and be fast.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

What Is and Is Not

Building trust takes time. Tearing it apart does not.

Building trust takes time. Tearing it apart does not.

Seeing what is there is easy. Seeing what is missing is not.

Concentrating is easy for some. For others, daydreaming is not.

Bringing your whole self to work takes courage. Pretending does not.

Hearing is easy. Listening is not.

Trying is subjective. Doing is not.

Telling the truth is appreciated. Done unskillfully, it is not.

Singing is easy for some. For others, not singing is not.

Going fast can be good. Going too fast cannot.

Hearing what is said is easy. Hearing what is withheld is not.

Finishing takes a long time. Quitting should not.

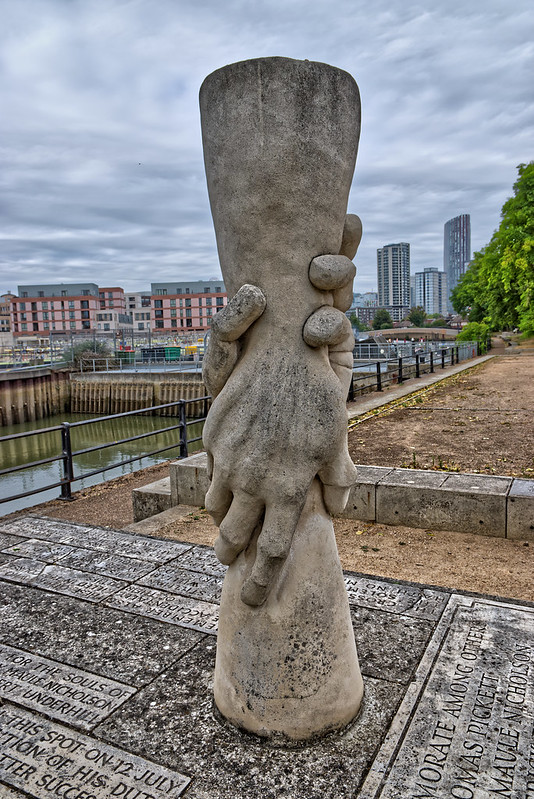

Image credit — Mike Keeling

Bringing Your Whole Self To The Party

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

If it’s taken from you, you’ll have a problem if you think it was yours.

When it’s taken from you, it doesn’t matter if it was never yours.

No one can take anything from you unless you think it is yours.

There can be no loss if it was never yours to have.

You can be manipulated if they know you have a problem letting go.

Said differently, if you can let go you can’t be manipulated.

Whether you want to admit it or not, it all goes away.

But if you see your favorite mug as already broken, there’s no problem when it breaks.

If you recognize your thirties will end, you won’t feel slighted when you start your fourth decade.

And it’s the same when you start your your fifth.

When you know things will end, their ending comes easier.

When you’re aware it will end, you can do it your way.

When you’re aware it’s finite, it’s easier to do what you think is right.

When you’re it all goes away, you can better appreciate what you have.

When you’re aware everything has a half-life, you’re less likely to live your life as a half-person.

Wouldn’t you like to do things your way?

Wouldn’t you like to do what you think is right?

Wouldn’t you like to live as a whole person?

Wouldn’t you like to appreciate what you have?

Would’t you like to bring your whole self to the party?

If so, why not embrace the impermanence?

Image credit — 正面顔〜〜〜(- .. -)

Improvement In Reverse Sequence

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can identify improvement opportunities, you must look for them.

Before you can look for improvement opportunities, you must believe improvement is possible.

Before believing improvement is possible, you must admit there’s a need for improvement.

Before you can admit the need for improvement, you must recognize the need for improvement.

Before you can recognize the need for improvement, you must feel dissatisfied with how things are.

Before you can feel dissatisfied with how things are, you must compare how things are for you relative to how things are for others (e.g., competitors, coworkers).

Before you can compare things for yourself relative to others, you must be aware of how things are for others and how they are for you.

Before you can be aware of how things are, you must be calm, curious, and mindful.

Before you can be calm, curious, and mindful, you must be well-rested and well-fed. And you must feel safe.

What choices do you make to be well-rested? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to be well-fed? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to feel safe? How do you feel about that?

Image credit — Philip McErlean

It’s not about failing fast; it’s about learning fast.

No one has ever been promoted by failing fast. They may have been promoted because they learned something important from an experiment that delivered unexpected results, but that’s fundamentally different than failure. That’s learning.

Failure, as a word, has the strongest negative connotations. Close your eyes and imagine a failure. Can you imagine a scenario where someone gets praised or promoted for that failure? I think not. It’s bad when you fail to qualify for a race. It’s bad when you fail to get that new job. It’s bad when driving down the highway the transmission fails fast. If you squint, sometimes you can see a twinkle of goodness in failure, but it’s still more than 99% bad.

When it’s bad for people’s careers, they don’t do it. Failure is like that. If you want to motivate people or instill a new behavior, I suggest you choose a word other than failure.

Learning, as a word, has highly positive connotations. Children go to school to learn, and that’s good. People go to college to learn, and that’s good. When people learn new things they can do new things, and that’s good. Learning is the foundation for growth and development, and that’s good.

Learning can look like failure to the untrained eye. The prototype blew up – FAILURE. We thought the prototype would survive the test, but it didn’t. We ran a good test, learned the weakest element, and we’re improving it now – LEARNING. In both cases, the prototype is a complete wreck, but in the FAILURE scenario, the team is afraid to talk about it, and in the LEARNING scenario they brag. In the LEARNING scenario, each team member stands two inches taller.

Learning yes; failure no.

The transition from failure to learning starts with a question: What did you learn? It’s a magic question that helps the team see the progress instead of the shattered remains. It helps them see that their hard work has made them smarter. After several what-did-you-learns, the team will start to see what they learned. Without your prompts, they’ll know what they learned. Then, they’ll design their work around their desired learning. Then they’ll define formal learning objectives (LOs). Then they’ll figure out how to improve their learning rate. And then they’re off to the races.

You don’t break things for the sake of breaking them. You break things so you can learn.

Learning yes; failure no. Because language matters.

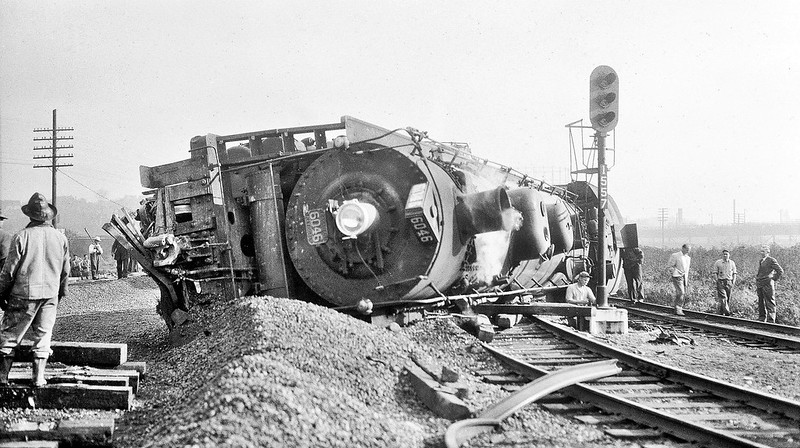

Image credit — mining camper

Wanting What You Have

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

Would you be happy or would you want something else?

Wanting doesn’t have a half-life. Regardless of how much we have, wanting is always right there with us lurking in the background.

Getting what you want has a half-life. After you get what you want, your happiness decays until what you just got becomes what you always had. I think they call that hedonistic adaptation.

When you have what you always had, you have two options. You can want more or you can want what you have. Which will you choose?

When you get what you want, you become afraid to lose what you got. There’s no free lunch with getting what you want.

When you want more, I can manipulate you. I wouldn’t do that, but I could.

When you want more your mind lives in the future where it tries to get what you want. And lives in the past where it mourns what you did not get or lost.

It’s easier to live in the present moment when you want what you have. There’s no need to craft a plan to get more and no need to lament what you didn’t have.

You can tell when a person wants what they have. They are kind because there’s no need to be otherwise. They are calm because things are good. And they are themselves because they don’t need anything from anyone.

Wanting what you have is straightforward. Whatever you have, you decide that’s what you want. It’s much different than having what you want. Once you have what you want hedonistic adaptation makes you want more, and then it’s time to jump back on the hamster wheel.

Wanting what you have is freeing. Why not choose to be free and choose to want what you have?

Image credit — Steven Guzzardi

How To Put Yourself Out There

When in doubt, put it out there. Easy to say, difficult to do.

When in doubt, put it out there. Easy to say, difficult to do.

Why not give it a go? What’s in the way? A better question: Who is in the way? I bet that who is you.

I’ve heard the fear of failure blocks people from running full tilt into new territory. Maybe. But I think the fear of success is the likely culprit.

If you go like hell and it doesn’t work, the consequences of failure are clear, immediate, and short-lived. It’s like skinning your knee. Everyone knows you went down hard and it hurts in the moment. And two days after the Band-Aid, you’re better.

If you run into the fire and succeed, the consequences are unknown, and there’s no telling when those consequences will find you. Will you be seen as an imposter? Will soar to new heights only to fail catastrophically and publicly? Will the hammer drop after this success or the next one? There’s uncertainty at every turn and our internal systems don’t like that.

Whether it’s the fear of success or failure, I think the root cause is the same: our aversion to being judged by others. We tell ourselves stories about what people will think about us if we fail and if we succeed. In both cases, our internal stories scratch at our self-image and make our souls bleed. And all this before any failure or success.

I think it’s impossible to stop altogether our inner stories. But, I think it is possible to change our response to our inner stories. You can’t stop someone from calling you a dog. But when they call a dog, you can turn around and look to see if you have a tail. And if you don’t have a tail, you can tell yourself objectively you’re not a dog. And I think that’s a good way to dismiss our internal stories.

The next time you have an opportunity put yourself out there, listen to the stories you tell yourself. Acknowledge they’re real and acknowledge they’re not true. They may call you a dog, but you have no tail. So, no, you’re not a dog.

You may fail or you may fail. But the only way to find out is to put yourself out there. Whether you fail or succeed, you don’t have a tail and you’re not a dog. So you might as well put yourself out there.

Image credit — Tambako the Jaguar

There’s no such thing as 100% disagreement.

Even when there is significant disagreement, there is not 100% disagreement.

Even when there is significant disagreement, there is not 100% disagreement.

Can both sides agree breathing is good for our health? I think so. And if so, there is less than 100% disagreement. Now that we know agreement is possible, might we stand together on this small agreement platform and build on it?

Can both sides agree all people are important? Maybe not. But what if we break it down into smaller chunks? Can we agree family is important? Maybe. Can we agree my family is important to me and your family is important to you? I think so. Now that we have some agreement, won’t other discussions be easier?

Can we agree we want the best for our families? I think so. And even though we don’t agree on what’s best for our families, we still agree we want the best for them. What if we focused on our agreement at the expense of our disagreement? Down the road, might this make it easier to talk to each other about what we want for our families? Wouldn’t we see each other differently?

But might we agree on some things we want for our families? Do both sides agree we want our families to be healthy? Do we agree we want them to be happy? Do we agree we want them to be well-fed? Do we want them to be warm and dry when the weather isn’t? With all this agreement, might we be on the same side, at least in this space?

But what about our country? Is there 100% disagreement here? I think not. Do we agree we want to be safe? Do we agree we want the people we care about to be safe? Do we agree we want good roads? Good bridges? Do we agree we want to earn a good living and provide for our families? It seems to me we agree on some important things about our country. And I think if we acknowledge our agreement, we can build on it.

I think there’s no such thing as 100% disagreement. I think you and I agree on far more things than we realize. When we meet, I will look for small nuggets of agreement. And when I find one, I will acknowledge our agreement. And I hope you will feel understood. And I hope that helps us grow our agreement into a friendship built on mutual respect. And I hope we can teach our friends to seek agreement and build on it.

I think this could be helpful for all of us. Do you agree?

Image credit — Orin Zebest

Swimming In New Soup

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

You know the space is new when you don’t have the right words to describe the phenomenon.

When there are two opposite sequences of events and you think both are right, you know the space is new.

You know you’re thinking about new things when the harder you try to figure it out the less you know.

You know the space is outside your experience but within your knowledge when you know what to do but you don’t know why.

When you can see the concept in your head but can’t drag it to the whiteboard, you’re swimming in new soup.

When you come back from a walk with a solution to a problem you haven’t yet met, you’re circling new space.

And it’s the same when know what should be but it isn’t – circling new space.

When your old tricks are irrelevant, you’re digging in a new sandbox.

When you come up with a new trick but the audience doesn’t care – new space.

When you know how an experiment will turn out and it turns out you ran an irrational experiment – new space.

When everyone disagrees, the disagreement is a surrogate for the new space.

It’s vital to recognize when you’re swimming in a new space. There is design freedom, new solutions to new problems, growth potential, learning, and excitement. There’s acknowledgment that the old ways won’t cut it. There’s permission to try.

And it’s vital to recognize when you’re squatting in an old space because there’s an acknowledgment that the old ways haven’t cut it. And there’s permission to wander toward a new space.

Image credit — Tambaco The Jaguar

When in doubt, start.

At the start, it’s impossible to know the right thing to do, other than the right thing is to start.

At the start, it’s impossible to know the right thing to do, other than the right thing is to start.

If you think you should have started, but have not, the only thing in the way is you.

If you want to start, get out of your own way, and start.

And even if you’re not in the way, there’s no harm in declaring you ARE in the way and starting.

If you’re afraid, be afraid. And start.

If you’re not afraid, don’t be afraid. And start.

If you can’t choose among the options, all options are equally good. Choose one, and start.

If you’re worried the first thing won’t work, stop worrying, start starting, and find out.

Before starting, you don’t have to know the second thing to do. You only have to choose the first thing to do.

The first thing you do will not be perfect, but that’s the only path to the second thing that’s a little less not perfect.

The second thing is defined by the outcome of the first. Start the first to inform the second.

If you don’t have the bandwidth to start a good project, stop a bad one. Then, start.

If you stop more you can start more.

Starting small is a great way to start. And if you can’t do that, start smaller.

If you don’t start, you can never finish. That’s why starting is so important.

In the end, starting starts with starting. This is The Way.

Image credit — Claudio Marinangeli

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski