Archive for the ‘Risk’ Category

The obligations of knowing your stuff.

If you know your shit, you have an obligation to behave that way:

Do – don’t ask.

Say, “I don’t know.”

Wear the clothes you want.

Tread water with Fear until she drowns.

Walk softly – leave your big stick at home.

Ask people what they think – let them teach you.

Kick Consensus in the balls – he certainly deserves it.

Be kind to those who should know – teach, don’t preach.

Hug the bullies – they cannot hurt you, you know too much.

Work with talented new folks – piss and ginger is a winning combination.

In short, use your powers for good – you have an obligation to yourself, your family, and society.

Obsolete your best work.

You solved a big problem in a meaningful way; you made a big improvement in something important; you brought new thinking to an old paradigm; you created something from nothing. Unfortunately, the easy part is over. Your work created the new baseline, the new starting point, the new thing that must be made obsolete. So now on to the hard part: to obsolete your best work

You solved a big problem in a meaningful way; you made a big improvement in something important; you brought new thinking to an old paradigm; you created something from nothing. Unfortunately, the easy part is over. Your work created the new baseline, the new starting point, the new thing that must be made obsolete. So now on to the hard part: to obsolete your best work

You know best how to improve your work, but you must have the right mindset to obsolete it. Sure, take time to celebrate your success (Remember, you created something from nothing.), but as soon as you can, grow your celebration into confidence, confidence to dismantle the thing you created. From there, elevate your confidence into optimism, optimism for future success. (You earned the right to feel optimistic; your company knows your next adventure may not work, but, hey, no one else will even try some of the things you’ve already pulled off.) For you, consequences of failure are negligible; for you, optimism is right.

Now, go obsolete your best work, and feel good about it.

Treat your parts like your children

There’s lots of charged debate these days on the strengths and weakness of in-sourcing and outsourcing. That’s good. But what’s a company to do?

There’s lots of charged debate these days on the strengths and weakness of in-sourcing and outsourcing. That’s good. But what’s a company to do?

I’d like to propose a new framework to think through the situation. I call it the Parental Framework. (I get to name it since I just invented it.) There’s only one tenet – think of your parts like your children.

When they’re young you take care of their every need. They cry and you jump. If not, they make you pay with sleepless nights.

As they grow you still take care of them. But now it’s about control. They gain independence and try to go where they want. You continually bring them back to center. Their independence scares you, and it should. You cringe when you think of what can happen to them. Take your eye off them for a minute and all hell could break loose.

When they go to school you become deeply concerned with the systems and processes that control the quality of their education.

Before you dare go out for a nice evening with your spouse (I heard that happens now and again), you do background checks on potential babysitters because the consequences of a bad one are severe. The slightest question of the sitter’s capability fills you with anxiety. No chance of connecting with your spouse. It’s all about the little ones.

The Parental Framework may be a bridge too far, but I find it helpful. I like thinking about my parts as my children. It works for me.

Doing New

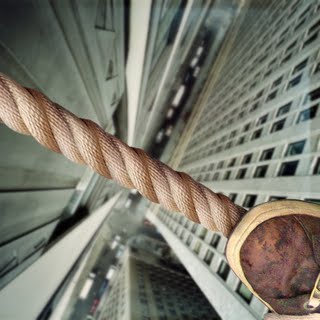

Doing new is hard and starting new is particularly hard. Once fear is overcome and new is started, doing new becomes a battle with discouragement. Not managed, discouragement can stop new.

Doing new is hard and starting new is particularly hard. Once fear is overcome and new is started, doing new becomes a battle with discouragement. Not managed, discouragement can stop new.

Slumped shoulders and a head hung low are the signs and a mismatch with expectations is the source. Expectations are defined in the form of a project plan, but, since the work is new, expectations are not grounded, not calibrated. How long will it take to do something we’ve never dreamed of doing? Yet when disguised as a project plan, uncalibrated expectations become a hard deadline.

When you want to do new, you give the project to your best. When they use the right tools, the latest data, and the best processes, yet new does not come per the plan, your best can become discouraged. But this discouragement is misplaced. Sure, the outcome is different from the plan, but reality isn’t the problem, it’s the plan, the expectations. They did everything right, so tell them. Tell them the expectations are out of line. Tell them you think their doing a good job. Tell them if it was easy, you’d have given the project to someone else. Tell them they can feel discouraged for five more minutes, but then they’ve got to go back, look new in the eye, and kick its ass.

Inspiring Work

Inspiring work is art.

Inspiring work is art.

Inspiring work is rare.

Inspiring work is scary.

Inspiring work is thrilling.

Inspiring work is the reward.

Inspiring work is life changing.

Inspiring work is easy to recognize.

Inspiring work is difficult to recognize.

Inspiring work is an acknowledgment of self.

Inspiring work’s magnitude is proportional to the fear.

With Innovation, It’s Trust But Verify.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Your best engineer walks into your office and says, “I have this idea for a new technology that could revolutionize our industry and create new markets, markets three times the size of our existing ones.” What do you do? What if, instead, it’s a lower caliber engineer that walks into your office and says those same words? Would you do anything differently? I argue you would, even though you had not heard the details in either instance. I think you’d take your best engineer at her word and let her run with it. And, I think you’d put less stock in your lesser engineer, and throw some roadblocks in the way, even though he used the same words. Why? Trust.

Innovation is largely a trust-based sport. We roll the dice on folks that have already put it on the table, and, conversely, we raise the bar on those that have not yet delivered – they have not yet earned our trust. Seems rational and reasonable – trust those who have earned it. But how did they earn your trust the first time, before they delivered? Trust.

There is no place for trust in the sport of innovation. It’s unhealthy. Ronald Reagan had it right:

Trust, but verify.

As we know, he really meant there was no place for trust in his kind of sport. Every action, every statement had to be verified. The consequences so cataclysmic, no risk could be tolerated. With innovation consequences are not as severe, but they are still substantial. A three year, multi-million (billion?) dollar innovation project that returns nothing is substantial. Why do we tolerate the risk that comes with our trust-based approach? I think it’s because we don’t think there’s a better way. But there is. What we need is some good, old-fashioned verification mixed in with our innovation.

When the engineer comes into your office and says she can reinvent your industry, what do you ask yourself? What do you want to verify? You want to know if the new idea is worth a damn, if it will work, if there are fundamental constraints in the way. But, unfortunately for you, verification requires knowledge of the physics, and you’re no physicist. However, don’t lose hope. There are two simple tactics, non-technical tactics, to help with this verification business.

First – ask the engineers a simple question, “What conflict is eliminated with the new technology?” Good, innovative technologies eliminate fundamental, long standing conflicts. These long standing conflicts limit a technology in a way that is so fundamental engineers don’t even know they exist. When a fundamental conflict is eliminated, long held “design tradeoffs” no longer apply, and optimizing is replaced by maximizing. With optimizing, one aspect of the design is improved at the expense of another. With maximizing, both aspects of the design are improved without compromise. If the engineers cannot tell you about the conflict they’ve eliminated, your trust has not been sufficiently verified. Ask them to come back when they can answer your question.

Second – when they come back with their answer, it will be too complex to be understood, even by them. Tell them to come back when they can describe the conflict on a single page using a simple block diagram, where the blocks, labeled with everyday nouns, represent parts of the design intimately involved with the conflict, and the lines, labeled with everyday verbs, represent actions intimately involved with the conflict. If they can create a block diagram of the conflict, and it makes sense to you, your trust has been sufficiently verified. (For a post with a more detailed description of the block diagrams, click on “one page thinking” in the Category list.)

Though your engineers won’t like it at first, your two-pronged verification tactics will help them raise their game, which, in turn, will improve the risk/reward ratio of your innovation work.

Reducing the risk of Innovation

Though we can’t describe it in words, or tell someone how to do it, we all know innovation is good. Why is it good? Look at the causal chain of actions that create a good economy, and you’ll find innovation is the first link.

Though we can’t describe it in words, or tell someone how to do it, we all know innovation is good. Why is it good? Look at the causal chain of actions that create a good economy, and you’ll find innovation is the first link.

When innovation happens, a new product is created that does something that no other product has done before. It provides a new function, it has a new attribute that is pleasing to the eye, it makes a customer more money, or it simply makes a customer happy. It does not matter which itch it scratches, the important part is the customer finds it valuable, and is willing to pay hard currency for it. Innovation does something amazing, it results in a product that creates value; it creates something that’s worth more than the sum of its parts. Starting with things dug from the ground or picked from it – dirt (steel, aluminum, titanium), rocks (minerals/cement/ceramics), and sticks (wood, cotton, wool), and adding new thinking, a product is created, a product that customers pay money for, money that is greater than the cost of the dirt, rocks, sticks, and new thinking. This, my friends, is value creation, and this is what makes national economies grow sustainably. Here’s how it goes.

Customers value the new product highly, so much so that they buy boatloads of them. The company makes money, so much so stock price quadruples. With its newly-stuffed war chest, the company invests with confidence, doing more innovation, selling more products, and making more money. An important magazine writes about the company’s success, which causes more companies to innovate, sell, and invest. Before you know it, the economy is flooded with money, and we’re off to the races in a sustainable way – a way based on creating value. I know this sounds too simplistic. We’ve listened too long to the economists and their theories – spur demand, markets are efficient, and the world economy thing. This crap is worse than it sounds. Things don’t have to be so complicated. I wish economists weren’t so able to confuse themselves. Innovate, sell, and invest, that’s the ticket for me.

Innovation – straightforward, no, easy, no. Innovation is scary as hell because it’s risky as hell. The risk? A company tries to develop a highly innovative product, nothing comes out the innovation tailpipe, and the company has nothing for its investment. (I can never keep the finance stuff straight. Does zero return on a huge investment increase or decrease stock price?) It’s the tricky risk thing that gets in the way of innovation. If innovation was risk free, we’d all be doing it like voting in Chicago – early and often. But it’s not. Although there is a way to shift the risk/reward ratio in our favor.

After doing innovation wrong, learning, and doing it less wrong, I have found one thing that significantly and universally reduces the risk/reward ratio. What is it?

Know you’re working on the right problem.

Work on the right problem? Are you kidding? This is the magic advice? This is the best you’ve got? Yes.

If you think it’s easy to know you’re working on the right problem, you’ve never truly known you were working on the right problem, because this type of knowing is big medicine. Innovation is all about solving a special type of problem, problems caused by fundamental conflicts and contradictions, things that others don’t know exist, don’t know how to describe, or define, let alone know how to eliminate. I’m talking about conflicts and contradictions in the physics sense – where something must be hot and cold at the same time, something must be big while being small, black while white, hard one instant, and soft the next. Solve one of those babies, and you’ve innovated yourself a blockbuster product.

In order to know you’re working on the right problem (conflict or contradiction), the product is analyzed in the physics sense. What’s happening, why, where, when, how? It’s the rule (not the exception) that no one knows what’s really going on, they only think they do. Since the physics are unknown, a hypothesis of the physics behind the conflict/contradiction must be conjured and tested. The hypothesis must be tests analytically or in the lab. All this is done to define the problem, not solve it. To conjure correctly, a radical and seemingly inefficient activity must be undertaken. Engineers must sit at their desk and think about physics. This type of thinking is difficult enough on its own and almost impossible when project managers are screaming at them to get off their butts and fix the problem. As we know, thinking is not considered progress, only activity is.

After conjuring the hypothesis, it’s tested to prove or disprove. If dis-proven, back to the desk for more thinking. If proven, the conflict/contradiction behind the problem is defined, and you know you’re working on the right problem. You have not solved it, you’ve only convinced yourself you’re working on the right one. Now the problem can be solved.

Believe it or not, solving is the easy part. It’s easy because the physics of the problem are now known and have been verified in the lab. We engineers can solve physics problems once they’re defined because we know the rules. If we don’t know the physics rules off the top of our heads, our friends do. And for those tricky times, we can go to the internet and ask Google.

I know all this sounds strange. That’s okay, it is. But it’s also true. Give your engineers the tools, time and training to identify the problems, conflicts, and contradictions and innovation will follow. Remember the engineering paradox, sometimes slower is faster. And what about those tools for innovation? I’ll save them for another time.

Engineers and Change?

As an engineering leader I work with design engineers every day. I like working with them, it’s fun. It’s comfortable for me because I understand us. Yes, I am an engineer.

As an engineering leader I work with design engineers every day. I like working with them, it’s fun. It’s comfortable for me because I understand us. Yes, I am an engineer.

I know what we’re good at, and I know we’re not good at. I’ve heard the jokes. Some funny, some not. But when engineers and non-engineers work well together, there’s lots of money to be made. I figure it’s time to explain how engineers tick so we can make more money. An engineer explaining engineers, to non-engineers – a flawed premise? Maybe, but I’ll roll the dice.

Everyone knows why design engineers are great to have around. Want a new product? Put some design engineers on it. Want to solve a tough technical problem? Put some design engineers on it. Want to create something from nothing? Design engineers. Everyone also knows we can be difficult to work with. (I know I can be.) How can we be high performing in some contexts and low performing in others? What causes the flip between modes? Understanding what’s behind this dichotomy is the key to understanding engineers. What’s behind this? In a word, “change”. And if you understand change from an engineer’s perspective, you understand engineers. If you remember just one sentence, here it is:

To engineers, change equals risk, and risk is bad.

Why do we think that way? Because that’s who we are; we’re walking risk reduction machines. And that’s good because in this time of doing more, doing it with less, and doing it faster, companies are taking more risk. Engineers make sure risk is always part of the risk-reward equation.

The best way to explain how engineers think about change and risk is to give examples. Here three examples.

Changing a drawing for manufacturing

Several months after product launch, with things running well, there is a request to change an engineering print. Change the print? That print is my recipe. I know how it works and when it doesn’t. That recipe works. My job is to make sure it works, and someone wants to change it? I’m not sure it will work. Did I tell you it’s my job to make sure it works? I don’t have time to test it thoroughly. Remember, when I say it will work, you expect that it will. I’m not sure the change will work. I don’t want to take the risk. Change is risk.

Changing the specification

This is a big one. Three months into a new product development project, the performance specification is changed, moving it north into unknown territory. The customer will benefit from the increased performance, we understand this, but the change created risk. The knowledge we created over the last three months may not be relevant, and we may have to recreate it. We want to meet the new specification (we’re passionate about product and technology), but we don’t know if we can. You count on us to be sure that things will work, and we pride ourselves on our ability to do that for you. But with the recent specification change, we’re not sure we can get it done. That’s risk, that’s uncomfortable for us, and that’s the reason we respond as we do to specification changes. Change is risk.

Changing how we do product development

This is the big one. We have our ways of doing things and we like them. Our design processes are linear, rational, and make sense (to us). We know what we can deliver when we follow our processes; we know about how long it will take; and we know the product will work when we’re done. Low risk. Why do you want us to change how we do things? Why do you want to add risk to our processes? All we’re trying to do is deliver a great product for you. Change is risk.

Engineers have a natural bias toward risk reduction. I am not rationalizing or criticizing, just explaining. We don’t expect zero risk; we know it’s about risk optimization and not risk minimization. But it’s important to keep your eye on us to make sure our risk pendulum does not swing too far toward minimization. The great American philosopher Mae West said, “Too much of a good thing can be wonderful.” But that’s not the case here.

When it comes to engineers and risk reduction, too much of a good thing is not wonderful.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski