Archive for the ‘Risk’ Category

Choose Yourself

We’ve been conditioned to ask for direction; to ask for a plan; and ask for permission. But those ways no longer apply. Today that old behavior puts you at the front of the peloton in the great race to the bottom.

We’ve been conditioned to ask for direction; to ask for a plan; and ask for permission. But those ways no longer apply. Today that old behavior puts you at the front of the peloton in the great race to the bottom.

The old ways are gone.

Today’s new ways: propose a direction (better yet, test one out on a small scale); create and present a radical plan of your own (or better, on the smallest of scales test the novel aspects and present your learning); and demonstrate you deserve permission by initiating activity on something that will obsolete the very thing responsible for your success.

People that wait for someone to give them direction are now a commodity, and with commodities it always ends in the death spiral of low cost providers putting each other out of business. As businesses are waist deep in proposals to double-down on what hasn’t worked and are choking on their flattened S-curves, there’s a huge opportunity for people that have the courage to try new things on their own. Today, if you initiate you’ll differentiate.

[This is where you say to yourself – I’ve already got too much on my plate, and I don’t have the time or budget to do more (and unsanctioned) work. And this is where I tell you your old job is already gone, and you might as well try something innovative. It’s time to grab the defibrillator and jolt your company out of its flatline. ]

It’s time to respect your gut and run a low cost, micro-experiment to test your laughable idea. (And because you’ll keep the cost low, no one will know when it doesn’t go as you thought. [They never do.]) It’s time for an underground meeting with your trusted band of dissidents to plan and run your pico-experiment that could turn your industry upside down. It’s time to channel your inner kindergartener and micro-test the impossible.

It’s time to choose yourself.

Incomplete Definition – A Way Of Life

At the start of projects, no one knows what to do. Engineering complains the specification isn’t fully defined so they cannot start, and marketing returns fire with their complaint – they don’t yet fully understand the customer needs, can’t lock down the product requirements, and need more time. Marketing wants to keep things flexible and engineering wants to lock things down; and the result is a lot of thrashing and flailing and not nearly enough starting.

At the start of projects, no one knows what to do. Engineering complains the specification isn’t fully defined so they cannot start, and marketing returns fire with their complaint – they don’t yet fully understand the customer needs, can’t lock down the product requirements, and need more time. Marketing wants to keep things flexible and engineering wants to lock things down; and the result is a lot of thrashing and flailing and not nearly enough starting.

Both camps are right – the spec is only partially formed and customer needs are only partially understood – but the project must start anyway. But the situation isn’t as bad as it seems. At the start of a project fully wrung out specs and fully validated customer needs aren’t needed. What’s needed is definition of product attributes that set its character, definition of how those attributes will be measured, and definition of the competitive products. The actual values of the performance attributes aren’t needed, just their name, their relative magnitude expressed as percent improvement, and how they’ll be measured.

And to do this the project manager asks the engineering and marketing groups to work together to create simple bar charts for the most important product attributes and then schedules the meeting where the group jointly presents their single set of bar charts.

This little trick is more powerful than it seems. In order to choose competitive products, a high level characterization of the product must be roughed out; and once chosen they paint a picture of the landscape and set the context for the new product. And in order to choose the most important performance (or design) attributes, there must be convergence on why customers will buy it; and once chosen they set the context for the required design work.

Here’s an example. Audi wants to start developing a new car. The marketing-engineering team is tasked to identify the competitive products. If the competitive products are BMW 7 series, Mercedes S class, and the new monster Hyundai, the character of the new car and the character of the project are pretty clear. If the competitive products are Ford Focus, Fiat F500, and Mini Cooper, that’s a different project altogether. For both projects the team doesn’t know every specification, but it knows enough to start. And once the competitive products are defined, the key performance attributes can be selected rather easily.

But the last part is the hardest – to define how the performance characteristics will be measured, right down to the test protocols and test equipment. For the new Audi fuel economy will be measured using both the European and North American drive cycles and measured in liters per 100 kilometer and miles per gallon (using a pre-defined fuel with an 89 octane rating); interior noise will be measured in six defined locations using sound meter XYZ and expressed in decibels; and overall performance will be measured by the lap time around the Nuremburg Ring under full daylight, dry conditions, and 25 Centigrade ambient temperature, measured in minutes.

Bar charts are created with the names of the competitive vehicles (and the new Audi) below each bar and performance attribute (and units, e.g., miles per gallon) on the right. Side-by-side, it’s pretty clear how the new car must perform. Though the exact number is not know, there’s enough to get started.

At the start of a project the objective is to make sure you’re focusing on the most performance attributes and to create clarity on how the attributes (and therefore the product) will be measured. There’s nothing worse than spending engineering resources in the wrong area. And it’s doubly bad if your misplaced efforts actually create constraints that limit or reduce performance of the most important attributes. And that’s what’s to be avoided.

As the project progresses, marketing converges on a detailed understanding of customer needs, and engineering converges on a complete set of specifications. But at the start, everything is incomplete and no part of the project is completely nailed down.

The trick is to define the most important things as clearly as possible, and start.

The Confusing Antimatter of Novelty

In a confusing way, the seemingly negative elements of novelty are actually tell-tale signs you’re doing it right. Here are some examples:

No uncertainty, no upside.

No heresy, no game-changer.

No recipe, no worries.

No ambiguity, no new markets.

No effectiveness, no success.

No efficiency, no matter.

No disagreement, no gravity.

No answers, no problem.

No problem, no innovation.

No dispute, no dilemma.

No headache, no quandary.

No obstacle, no predicament.

No unrest, no virtue.

No failure, no creativity.

No discomfort, no relevance.

No agitation, no consequence.

No questions, no significance.

No best practice, no anxiety.

No downside, no upside.

On Being Well Rested

All business processes are powered by people. Even with all our automation and standardization, nothing moves without people. And people are powered by language. Language is important.

All business processes are powered by people. Even with all our automation and standardization, nothing moves without people. And people are powered by language. Language is important.

“Fix that so we don’t make any more mistakes.” Snarl words. “Figure out what we do well, and let’s do more of that.” Purr words. Which are more powerful?

“Wonderful work.” Purr words. “Wonderful, more customer complaints.” Snarl words. The same word is both, but it’s clear to all which is which. One is empowering, the other demotivating. Which is better for business?

Subtle usage makes a difference, intonation makes a difference, and tone makes a difference. It’s not just words that matter, but how they’re delivered also matters. Words can build or words can dismantle, and so can delivery.

We know people drive everything. And we know words influence people. Yet we don’t use words in ways that respects their gravity.

It takes care to use the right words in the right ways, and it takes thoughtfulness. But with today’s race pace, it’s tough to be well rested which makes it tough to use care and forethought. Well rested shouldn’t be a luxury and shouldn’t be scoffed at. In an instant the wrong words at the wrong time can be catastrophic. Trouble is the value of being well rested cannot be quantified on the balance sheet.

People power processes and words power people, and the right words at the right time can make all the difference. But it takes thoughtful, enlightened people to deliver them. And for that, they should be well rested.

More Risk, Less Consequence

WHY? To grow sales in existing markets and create sales in new markets.

WHY? To grow sales in existing markets and create sales in new markets.

WHAT? Create innovative technologies and design products with more function and less cost.

HOW? Educate the engineering engine.

This is easier said than done, because for years we’ve set one-sided expectations – new products must work and timelines must be met – and driven risk tolerance out of our engineering engine. Now it’s time to inject it back in.

The message – Our thinking must change. We must take more risk, but do it safely by reducing negative consequences of risk.

To reduce negative consequences of risk, we must learn to localize risk through the narrowest and deepest problem definition, and learn to secure the launch so it’s safe to try new things.

We must do more up-front technology work, but learn to do it far more narrowly and deeply. We must learn to hold ourselves accountable to rigorous problem definition, and we must put our best people on technology projects.

To focus creativity we must learn to set seemingly unrealistic time constraints; to focus our actions we can look to a powerful mantra – spend a little, learn a lot.

The trouble with new thinking is it takes new thinking. If you don’t have it, go get it. If you already have it, figure out why you haven’t used it.

Mindset for Doing New

The more work I do with innovation, the more I believe mindset is the most important thing. Here’s what I believe:

The more work I do with innovation, the more I believe mindset is the most important thing. Here’s what I believe:

Doing new doesn’t take a lot of time; it’s getting your mind ready that takes time.

Engineers must get over their fear of doing new.

Without a problem there can be no newness.

Problem definition is the most important part of problem solving.

If you believe it can work or it can’t, you’re right.

Activity is different from progress.

Thinking is progress.

In short, I believe state-of-the-art is limited by state-of-mind.

Work The Rule

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the reason for the rule is no longer, do you follow it or declare it unreasonable?

If you don’t understand the rule do you work to understand it, or conveniently trespass?

If you don’t follow the rule, does that say something about the rule, or you?

When is a rule a rule and when is it shackles?

When it comes to law, physics, and safety, a rule is a rule.

If you’re limited by the rule, is it bad? (Isn’t far worse if you don’t realize it?)

What if the solution demands unruliness?

If you don’t follow rules, is it okay to make them?

What if a culture is so strong it rules out most everything, except following the rules?

What if a culture is so strong it demands you make the rules?

When it comes to rules, there’s only one rule – You decide.

I will hold a Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

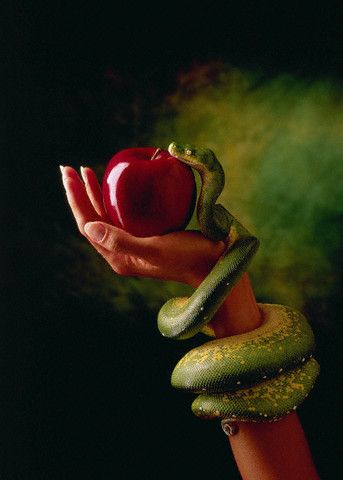

The Forbidden Fruit of Failure

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

Failure is learning in the form of experiments (including the thought kind) with outcomes different than theorized, where the outcomes create a more complete understanding of theory, or learning.

Wrong is mapped to failure, but failure should be mapped with – different than our best understanding.

Newness is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more newness, more learning. This is why tolerance of failure (and newness) is a must – no newness, no failure, no learning.

Risk is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more risk, more learning. Risk cannot be forbidden, if we’re to learn.

Risk and newness are mapped to late, and, guilt by association, failure is mapped to late. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – learn fast to avoid being late. And now, after several paragraphs of un-mapping, hopefully the re-substitution makes sense – fail fast to avoid being late.

Failure isn’t failure, failure is learning.

Manage For The Middle

Year-end numbers, quarter-to-quarter earnings, monthly production, week-to-week payroll. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Close-in focus is needed, it drives good stuff – vital few, productivity, quality, speed, and stock price. Without question, the close-in lens has value.

Year-end numbers, quarter-to-quarter earnings, monthly production, week-to-week payroll. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Close-in focus is needed, it drives good stuff – vital few, productivity, quality, speed, and stock price. Without question, the close-in lens has value.

But there’s a downside to this lens. Like a microscope, with one eye closed and the other looking through the optics, the fine detail is clear, but the field of view is small. Sure the object can be seen, but that’s all that can be seen – a small circle of light with darkness all around. It’s great if you want to see the wings of a fly, but not so good if you want to see how the fly got there.

Millennia, centuries, grand children, children. With today’s hyper-competition, today’s focus is today. Long-range focus is needed, it drives good stuff – infrastructure, building blocks, strategic advantage. Though it’s an underused lens, without question, the far-out lens has value.

But there’s a downside to this lens. Like a telescope, with one eye closed and the other looking through the optics, the field of view is enormous, but the detail is not there. Sure the far off target can be seen, but no details – a small circle of light without resolution. It’s great if you want to see a distant landscape, but not so good if you want to know what the trees look like.

What we need is a special set of binoculars. In the left is a microscope to see close-in – the details – and zoom out for a wider view – the landscape. In the right is a telescope to see far-out – the landscape – and zoom in for a tighter view – the details.

Unfortunately the physics of business don’t allow overlap between the lenses. The microscope cannot zoom out enough and the telescope cannot zoom in enough. There’s always a gap, the middle is always out of focus, unclear. Sure, we estimate, triangulate, and speculate (some even fabricate), but the middle is fuzzy at best.

It’s easy to manage for the short-term or long-term. But the real challenge is to manage for the middle. Fuzzy, uncertain, scary – it takes judgment and guts to manage for the middle. And that’s just where the best like to earn their keep.

Trust is better than control.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Although it’s more important than ever, trust is in short supply. With everyone doing three jobs, there’s really no time for anything but a trust-based approach. Yet we’re blocked by the fear that trust means loss of control. But that’s backward.

Trust is a funny thing. If you have it, you don’t need it. If you don’t have it, you need it. If you have it, it’s clear what to do – just behave like you should be trusted. If you don’t have it, it’s less clear what to do. But you should do the same thing – behave like you should be trusted. Either way, whether you have it or not, behave like you should be trusted.

Trust is only given after you’ve behaved like you should be trusted. It’s paid in arrears. And people that should be trusted make choices. Whether it’s an approach, a methodology, a technology, or a design, they choose. People that should be trusted make decisions with incomplete data and have a bias for action. They figure out the right thing to do, then do it. Then they present results – in arrears.

I can’t choose – I don’t have permission. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose. Of course you don’t have permission. Like trust, it’s paid in arrears. You don’t get permission until you demonstrate you don’t need it. If you had permission, the work would not be worth your time. You should do the work you should have permission to do. No permission is the same as no trust. Restating, I can’t choose – I don’t have trust. To that I say you’ve chosen not to choose.

There’s a misperception that minimizing trust minimizes risk. With our control mechanisms we try to design out reliance on trust – standardized templates, standardized process, consensus-based decision making. But it always comes down to trust. In the end, the subject matter experts decide. They decide how to fill out the templates, decided how to follow the process, and decide how consensus decisions are made. The subject matter experts choose the technical approach, the topology, the materials and geometries, and the design details. Maybe not the what, but they certainly choose the how.

Instead of trying to control, it’s more effective to trust up front – to acknowledge and behave like trust is always part of the equation. With trust there is less bureaucracy, less overhead, more productivity, better work, and even magic. With trust there is a personal connection to the work. With trust there is engagement. And with trust there is more control.

But it’s not really control. When subject matter experts are trusted, they seek input from project leaders. They know their input has value so they ask for context and make decisions that fit. Instead of a herd of cats, they’re a swarm of bees. Paradoxically, with a trust-based approach you amplify the good parts of control without the control parts. It’s better than control. It’s where ideas, thoughts and feelings are shared openly and respectfully; it’s where there’s learning through disagreement; it’s where the best business decisions are made; it’s where trust is the foundation. It’s a trust-based approach.

Coaxing out of the weeds.

Doing new is difficult and scary. For safety, we create complexity and hide behind it; we swim for the weeds; we dive for the details. (At least we’ll come across as knowledgeable about something when we bury our heads in details.) All of this so we can look smart and feel safe.

Doing new is difficult and scary. For safety, we create complexity and hide behind it; we swim for the weeds; we dive for the details. (At least we’ll come across as knowledgeable about something when we bury our heads in details.) All of this so we can look smart and feel safe.

But with new stuff, looking smart and feeling safe are not valid. With new, we don’t know; we’re not smart (yet); there’s no reason to feel safe. (Don’t try, it’s too slow.)

It takes focus and compassion to coax people out of the weeds and help them feel safe. Focus is needed to keep the end game in mind, to constantly keep context in the forefront (why are we here?), to maintain the right compass heading (into the wind). Compassion is needed to make “I don’t know” feel safe. To start, explain the deal: “new” and “I don’t know” are inseparable, a matched set. Like your best pair of wool socks, left without right doesn’t work. If that’s insufficient, tell them if was easy you’d have asked someone else to do it.

Day-to-day, it’s difficult to maintain focus and compassion. I find it helpful to remember it’s natural to seek safety in the weeds. We all do it. Keep that in mind while you do new as fast as you can.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski