Archive for the ‘Risk’ Category

A most powerful practice – Try It.

The first question is usually – What’s the best practice? And the second question is – Why aren’t you using it? In the done-it-before domain this makes sense. Best practices are best when inputs are tightly controlled, process steps are narrowly defined, and the desired output is known and can be formally defined.

The first question is usually – What’s the best practice? And the second question is – Why aren’t you using it? In the done-it-before domain this makes sense. Best practices are best when inputs are tightly controlled, process steps are narrowly defined, and the desired output is known and can be formally defined.

Industry loves best practice because they are so productive. Like the printing press, best practices are highly effective when it’s time to print the same pages over and over. It worked here, so do it there. And there. And there. Use the same typeface and crank it out – page by page. It’s like printing money.

Best practices are best utilized in the manufacturing domain, until they’re not. Which best practice should be used? Can it be used as-is, or must it change? And, if a best practice is changed, which version is best? Even in the tightly controlled domain of manufacturing, it’s tricky to effectively use best practices. (Maybe what’s needed is a best practice for using best practices.)

Best practices can be good when there’s strong commonality with previous work, but when the work is purposefully different (think creativity and innovation), all bets are off. But that doesn’t stop the powerful pull of productivity from jamming round best practices into square holes. In the domain of different, everything’s different – the line of customer goodness, the underpinning technology and the processes to make it, sell it, and service it. By definition, the shape of a best practice does not fit work that has yet to be done for the first time.

What’s needed is a flexible practice that can handle the variability, volatility, and uncertainty of creativity/innovation. My favorite is called – Try It. It’s a simple process (just one step), but it’s a good one. The hard part is deciding what to try. Here are some ways to decide.

No-to-yes. Define the range of inputs for the existing products and try something outside those limits.

Less-with-far-less. Reduce the performance (yes, less performance) of the very thing that makes your product successful and try adolescent technologies with a radically lower cost structures. When successful, sell to new customers.

Lines of customer goodness. Define the primary line of customer goodness of your most successful product and try things that advance different lines. When you succeed, change all your marketing documents and sales tools, reeducate your sales force, and sell the new value to new customers.

Compete with no one. Define a fundamental constraint that blocks all products in your industry, try new ideas that compromise everything sacred to free up novel design space and break the constraint. Then, sell new products into the new market you just created.

IBE (Innovation Burst Event). Everything starts with a business objective.

There is no best way to implement the Try It process, other than, of course, to try it.

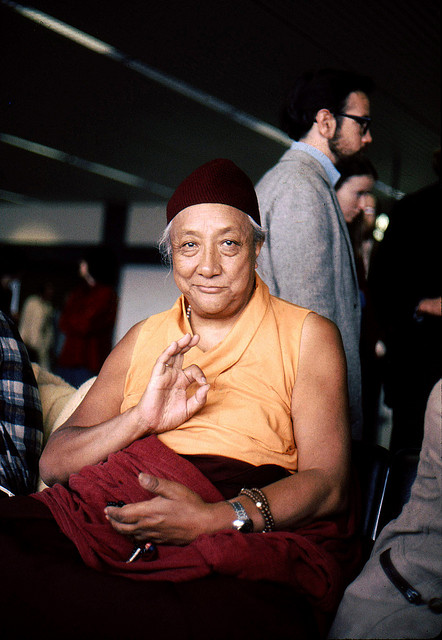

Image credit — Alland Dharmawan.

Accountability is not the answer.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

People have a natural bias toward doing what was done last time. The behavior is the result of untold generations that evolved to serve a single objective – to survive. Survival is about holding onto what is – protecting the family, providing food and waking up the next morning. In survival mode any energy spent on activities even partially unrelated to food, water and shelter is wasted energy. Any deviation from the worn path creates newness and uncertainty which causes adrenaline to flow and increases caloric burn rate. In survival mode the opportunity cost of those extra calories is larger than the potential benefit of a new experience.

Today, calories are readily available for most and survival is no longer the objective, yet the bias persists. Today, the bias is not driven by a culture of survivability. It’s driven by a culture of accountability. Accountability forces its own singular focus – make the numbers – and, like survivability, tightly links the consequences of mistakes and shortcomings to the individual. Spend your calories any way you want just don’t miss the numbers.

In a culture of accountability there is no time to rest and recharge. Like the predator that never sleeps, metrics continually keep a hungry eye on the human prey. And like with food and water, any deviation from the worn path of increased throughput and profit is unsafe behavior.

But when the watering hole dries up and the fruit has been picked from the trees, the worn path isn’t the safest path. Frantic foraging is the only real option, but it’s not much safer and certainly no way to go through life. Paradoxically, a culture of accountability, with its intent of reducing the risk of missing the numbers can create far more dangerous failure modes. Where over fishing depletes the fish population and over farming makes for a dust bowl, over reliance on what worked last time can create failure modes that jeopardize survival.

To break the bias and help people do new things, measure new things and talk about new things. Start the next meeting with a review of what’s different. The team will feel energized. And after the discussion, adjourn the meeting because everything else is the same. At the next status meeting, talk only about the surprising insights. With the next email, send praise about the new learning. At team meetings, acknowledge the inherent uncertainty of doing new things and praise it over the potentially catastrophic consequences of over extending the tried-and-true. And for metrics, stop measuring outcomes.

Image credit — Applied Nomadology

Strategic Planning is Dead.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

Things are no longer predictable, and it’s time to start behaving that way.

In the olden days (the early 2000s) the pace of change was slow enough that for most the next big thing was the same old thing, just twisted and massaged to look like the next big thing. But that’s not the case today. Today’s pace is exponential, and it’s time to behave that way. The next big thing has yet to be imagined, but with unimaginable computing power, smart phones, sensors on everything and a couple billion new innovators joining the web, it should be available on Alibaba and Amazon a week from next Thursday. And in three weeks, you’ll be able to buy a 3D printer for $199 and go into business making the next big thing out of your garage. Or, you can grasp tightly onto your success and ride it into the ground.

To move things forward, the first thing to do is to blow up the strategic planning process and sweep the pieces into the trash bin of a bygone era. And, the next thing to do is make sure the scythe of continuous improvement is busy cutting waste out of the manufacturing process so it cannot be misapplied to the process of re-imagining the strategic planning process. (Contrary to believe, fundamental problems of ineffectiveness cannot be solved with waste reduction.)

First, the process must be renamed. I’m not sure what to call it, but I am sure it should not have “planning” in the name – the rate of change is too steep for planning. “Strategic adapting” is a better name, but the actual behavior is more akin to probe, sense, respond. The logical question then – what to probe?

[First, for the risk minimization community, probing is not looking back at the problems of the past and mitigating risks that no longer apply.]

Probing is forward looking, and it’s most valuable to probe (purposefully investigate) fertile territory. And the most fertile ground is defined by your success. Here’s why. Though the future cannot be predicted, what can be predicted is your most profitable business will attract the most attention from the billion, or so, new innovators looking to disrupt things. They will probe your business model and take it apart piece-by-piece, so that’s exactly what you must do. You must probe-sense-respond until you obsolete your best work. If that’s uncomfortable, it should be. What should be more uncomfortable is the certainty that your cash cow will be dismantled. If someone will do it, it might as well be you that does it on your own terms.

Over the next year the most important work you can do is to create the new technology that will cause your most profitable business to collapse under its own weight. It doesn’t matter what you call it – strategic planning, strategic adapting, securing the future profitability of the company – what matters is you do it.

Today’s biggest risk is our blindness to the immense risk of keeping things as they are. Everything changes, everything’s impermanent – especially the things that create huge profits. Your most profitable businesses are magnates to the iron filings of disruption. And it’s best to behave that way.

Image credit – woodleywonderworks

Change your risk disposition.

Innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Something that’s novel is something that’s different, and something that’s different creates uncertainty. And, as we know, uncertainty is the enemy of all things sacred.

Innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Something that’s novel is something that’s different, and something that’s different creates uncertainty. And, as we know, uncertainty is the enemy of all things sacred.

Lean and Six Sigma have been so successful that the manufacturing analogy has created a generation that expects all things to be predictable, controllable and repeatable. Above all else, this generation values certainty. Make the numbers; reduce variability; reduce waste; do it on time – all mantras of the manufacturing analogy, all advocates of predictability and all enemies of uncertainty.

With the manufacturing analogy, a culture of accountability is the natural end game (especially when it comes to outcomes), but what most don’t understand is a culture that values accountability of outcomes is a culture that cannot tolerate uncertainty. And what fewer understand is a culture intolerant of uncertainty is a culture intolerant of innovation.

By definition, innovation and uncertainty are a matched pair – you can’t have one without the other. You can have both or neither – that’s the rule. And though we usually use the word “risk” rather than “uncertainty”, risk is a result of uncertainty and uncertainty is the fundamental.

When a product is launched and it’s poorly received, it’s likely due to an untested value proposition. And the reason the value proposition went untested is uncertainty, uncertainty around the negative consequences of challenging authority. Someone on high decreed the value proposition was real and the organization, based on how leadership responded in the past, did not challenge the decree because the last person who challenged authority was fired, demoted or ostracized.

When the new product is 3% better than the last one, again, the enemy is uncertainty. This time it’s either uncertainty around what the customer will value or uncertainty around the ability to execute on technology work. The organization cannot tolerate the risk (uncertainty), so it does what it did last time.

When the new product has more new features and functions than it has a right to, intolerance to uncertainty is the root cause. This time it’s uncertainty around the negative consequences of prioritizing one feature over another. Said another way, it’s about uncertainty (and the resulting fear) around using judgement.

These three scenarios are reward looking, as the uncertainty has already negatively impacted the innovation work. To mitigate the negative impacts on innovation, uncertainty must be part of the equation from the outset.

When it’s time for you to call for more innovation, it’s also the time to acknowledge you want more uncertainty. And it’s not enough to say you’ll tolerate more uncertainty because that takes you off the hook and puts it all on the innovators. You must tell the company you expect more uncertainty. This is important because the innovators won’t limit their work by an unnaturally low uncertainty threshold, rather they’ll do the work demanded by the hyper-aggressive growth goals.

And when you ask for more uncertainty, it’s time to explicitly tell people you expect them to use their judgment more freely and more frequently. With uncertainty there is no best practice, but there is best judgment. And when your best people use their best judgement, uncertainty is navigated in the most effective way.

But, really, if you ask for more uncertainty you won’t get it. The level of uncertainty in the trenches is set by your risk disposition. People in your company know, based on leadership’s actions – what’s rewarded and what’s punished – the company’s risk disposition and it governs their actions. If you take the pulse of your portfolio of technology projects you will see your risk disposition. The thing to remember is your risk disposition is the boss and the level of innovation is subservient.

When the CEO demands you change the innovation work for the better, politely suggest a plan to change the company’s risk disposition. And when the CEO asks how to do that, politely suggest a visit to Jim McCormick’s website.

Image credit – Suzanne Gerber

Compete with No One

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

The apex of this glorious battle is reached when companies no longer have points of differentiation and resort to competing on price. This is akin to attrition warfare where heavy casualties are taken on both sides until the loser closes its doors and the winner emerges victorious and emaciated. This race to the bottom can only end one way – badly for everyone.

Trench warfare is no way for a company to succeed, and it’s time for a better way. Instead of competing head-to-head, it’s time to compete with no one.

To start, define the operating envelope (range of inputs and outputs) for all the products in the market of interest. Once defined, this operating envelope is off limits and the new product must operate outside the established design space. By definition, because the new product will operate with input conditions that no one else’s can and generate outputs no one else can, the product will compete with no one.

In a no-to-yes way, where everyone’s product says no, yours is reinvented to say yes. You sell to customers no one else can; you sell into applications no one else can; you sell functions no one else can. And in a wicked googly way, you say no to functions that no one else would dare. You define the boundary and operate outside it like no one else can.

Competing against no one is a great place to be – it’s as good as trench warfare is bad – but no one goes there. It’s straightforward to define the operating windows of products, and, once define it’s straightforward to get the engineers to design outside the window. The hard part is the market/customer part. For products that operate outside the conventional window, the sales figures are the lowest they can be (zero) and there are just as many customers (none). This generates extreme stress within the organization. The knee-jerk reaction is to assign the wrong root cause to the non-existent sales. The mistake – “No one sells products like that today, so there’s no market there.” The truth – “No one sells products like that today because no one on the planet makes a product like that today.”

Once that Gordian knot is unwound, it’s time for the marketing community to put their careers on the line. It’s time to push the organization toward the scary abyss of what could be very large new market, a market where the only competition would be no one. And this is the real hard part – balancing the risk of a non-existent market with the reward of a whole new market which you’d call your own.

If slugging it out with tenacious competitors is getting old, maybe it’s time to compete with no one. It’s a different battle with different rules. With the old slug-it-out war of attrition, there’s certainty in how things will go – it’s certain the herd will be thinned and it’s certain there’ll be heavy casualties on all fronts. With new compete-with-no-one there’s uncertainty at every turn, and excitement. It’s a conflict governed by flexibility, adaptability, maneuverability and rapid learning. Small teams work in a loosely coordinated way to test and probe through customer-technology learning loops using rough prototypes and good judgement.

It’s not practical to stop altogether with the traditional market share campaign – it pays the bills – but it is practical to make small bets on smart people who believe new markets are out there. If you’re lucky enough to have folks willing to put their careers on the line, competing with no one is a great way to create new markets and secure growth for future generations.

Image credit – mae noelle

Orchids and Innovation – Blooms from the Same Stem

Innovation is like growing orchids – both require a complex balance of environmental factors, both take seasoned green thumbs to sprout anything worth talking about, what worked last time has no bearing on this time, and they demand caring and love.

Innovation is like growing orchids – both require a complex balance of environmental factors, both take seasoned green thumbs to sprout anything worth talking about, what worked last time has no bearing on this time, and they demand caring and love.

A beautiful orchid is a result of something, and so is innovation. It all starts with the right seeds, but which variety? Which color? With orchids, there are 21,950 – 26,049 species found in 880 genera and with innovation there are far more options. So which one and why? Well, it depends.

It’s no small feat to grow orchids or innovate:

To propagate orchids from seed, you must work in sterile conditions. The seeds must be grown in a gelatinous substance that contains nutrients and growth hormones. You must also be very patient. It takes months for the first leaves to develop, and, even then, they will only be visible with a magnifying glass. Roots appear even later. It will be at least three, and possibly as many as eight years before you see a bloom. — http://www.gardeners.com/how-to/growing-orchids/5072.html

[This is one of the best operational definitions of innovation I’ve ever seen.]

But there’s another way:

It is far easier to propagate orchids by division. But remember that dividing a plant means forsaking blooms for at least a year. Also, the larger the orchid plant, the more flowers it will produce. Small divisions take many years to mature. — http://www.gardeners.com/how-to/growing-orchids/5072.html

So do you grow from seed or propagate by division? It depends. There are strengths and weaknesses of both methods, so which best practice is best? Neither – with orchids and innovation no practices are best, even the ones described in the best books.

If you’ve been successful growing other flowers, you’re success is in the way and must be unlearned. Orchids aren’t flowers, they’re orchids. And if you’ve been successful with lean and Six Sigma, you’ve got a culture that will not let innovation take seed. Your mindset is wrong and you’ve got to actively dismantle the hothouse you’ve built – there’s no other way. Orchids and innovation require the right growing climate – the right soil, the right temperature, the right humidity, the right amount of light, and caring. Almost the right trowel, almost the right pot, and almost the right mindset and orchids and innovation refuse to flower.

And at the start the right recipe is unknown, yet the plants and the projects are highly sensitive to imperfect conditions. The approach is straightforward – start a lot of seeds, start a lot of propagation experiments, and start a lot of projects. But in all cases, make them small. (Orchids do better in small pots.)

Good instincts are needed for the best orchids to come to be, and these instincts can be developed only one way – by growing orchids. Some people’s instincts are to sing to their orchids and some play them classical music, and they’re happy to do it. They’re convinced it makes for better and fuller blooms and who’s to say if it matters? With orchids, if you think it matters, the orchids think it matters, so it matters. And let’s not kid ourselves – innovation is no different.

With orchids and innovation, mindset, instincts, and love matter, maybe more than anything else. And for that, there are no best practices.

Image credit — lecercle.

Embrace Uncertainty

There’s a lot of stress in the working world these days, and to me, it all comes down to our blatant disrespect of uncertainty.

There’s a lot of stress in the working world these days, and to me, it all comes down to our blatant disrespect of uncertainty.

In today’s reality, we ask for plans then demand strict adherence to the deliverables – on time, on budget, or else. We treat plans like they’re chiseled in granite, when really it should be more like dry erase markers and a whiteboard. Our markets are uncertain; customers’ behaviors are uncertain; competitors’ actions are uncertain; supply chains are uncertain, yet our plans are plans don’t reflect that reality. And when we expect absolute predictability and accountability, we create stress and anxiety and our people don’t want to try new things because that adds another level of uncertainty.

With a flexible, rubbery plan the first step informs the second, and this is the basis for the logical shift from robust plans to resilient ones. Plans should be less about forcing adherence and more about recognizing deviation. Today’s plans demand early recognition of something that did follow the plan and today’s teams must have the authority to respond quickly. However, after years of denying the powerful force of uncertainty and shooting the messenger, we’ve trained our people to hide the deviations. And, with our culture of control and accountability, our teams require our approval before any type of change, so their response time is, well, not timely.

At our core, we know uncertainty is a founding principle in our universe, and now it’s time to behave that way. It’s time to look inside and decide to embrace uncertainty. Accept it or not, acknowledge it or not, uncertainty is here to stay. Here are some words to guide your journey:

- Resilient not robust.

- Early detection, fast response.

- Many small plans, done in parallel.

- Do more of what works, and less of what doesn’t.

- Plans are meant to be re-planned.

And if you’re into innovation, this applies doubly.

Image credit – dfbphotos.

Innovation’s Mantra – Sell New Products To New Customers

There are three types of innovation: innovation that creates jobs, innovation that’s job neutral, and innovation that reduces jobs.

There are three types of innovation: innovation that creates jobs, innovation that’s job neutral, and innovation that reduces jobs.

Innovation that reduces jobs is by far the most common. This innovation improves the efficiency of things that already exist – the mantra: do the same, but with less. No increase in sales, just fewer people employed.

Innovation that’s job neutral is less common. This innovation improves what you sell today so the customer will buy the new one instead of the old one. It’s a trade – instead of buying the old one they buy the new one. No increase in sales, same number of people employed.

Innovation that creates jobs is uncommon. This innovation radically changes what you sell today and moves it from expensive and complicated to affordable and accessible. Sell more, employ more.

Clay Christensen calls it Disruptive Innovation; Vijay Govindarajan calls it Reverse Innovation; and I call it Less-With-Far-Less.

The idea is the product that is sold to a relatively small customer base (due to its cost) is transformed into something new with far broader applicability (due to its hyper-low cost). Clay says to “look down” to see the new technologies that do less but have a super low cost structure which reduces the barrier to entry. And because more people can afford it, more people buy it. And these aren’t the folks that buy your existing products. They’re new customers.

Vijay says growth over the next decades will come from the developing world who today cannot afford the developed world’s product. But, when the price comes down (down by a factor of 10 then down by a factor of 100), you sell many more. And these folks, too, are new customers.

I say the design and marketing communities must get over their unnatural fascination with “more” thinking. To sell to new customers the best strategy is increase the number of people who can afford your product. And the best way to do that is to radically reduce the cost signature at the expense of features and function. If you can give ground a bit on the thing that makes your product successful, there is huge opportunity to reduce cost – think 80% less cost and 20% less function. Again, you sell new product to new customers.

Here’s a thought experiment to help put you in the right mental context: Create a plan to form a new business unit that cannot sell to your existing customers, must sell a product that does less (20%) and costs far less (80%), and must sell it in the developing world. Now, create a list of small projects to test new technologies with radically lower cost structures, likely from other industries. The constraint on the projects – you must be able to squeeze them into your existing workload and get them done with your existing budget and people. It doesn’t matter how long the projects take, but the investment must be below the radar.

The funny thing is, if you actually run a couple small projects (or even just one) to identify those new technologies, for short money you’ve started your journey to selling new products to new customers.

Put Yourself Out There

Put yourself out there. Let it hang out. Give it a try. Just do it. The reality is few do it, and fewer do it often. But why?

Put yourself out there. Let it hang out. Give it a try. Just do it. The reality is few do it, and fewer do it often. But why?

In a word, fear. But it cuts much deeper than a word. Here’s a top down progression:

What will they think of your idea? If you summon the courage to say it out loud, your fear is they won’t like it, or they’ll think it’s stupid. But it goes deeper.

What with they think of you? If they think your idea is stupid, your fear is they’ll think you’re stupid. But so what?

How will it conflict with what you think of you? If they think you’re stupid, your fear is it will conflict with what you think of you. Now we’re on to it – full circle.

What do you think of you? It all comes down to your self-image – what you think is it and how you think it will stand up against the outside forces trying to pull it apart. The key is “what you think” and “how you think”. Like all cases, perception is reality; and when it comes to judging ourselves, we judge far too harshly. Our severe self-criticism deflates us far below the waterline of reality, and we see ourselves far shallower than our actions decree.

You’re stronger and more capable than you let yourself think. But no words can help with that; for that, only action will do. Summon the courage to act and take action. Just do it. And to calm yourself before you jump, hold onto this one fact – others’ criticism has never killed anyone. Stung, yes. Killed, no. Plain and simple, you won’t die if you put yourself out there. And even the worst bee stings subside with a little ice.

I’m not sure why we’re so willing to abdicate responsibility for what we think of ourselves, but we do. So where you may have abdicated responsibility in the past, in the now it’s time to take responsibility. It’s time to take responsibility and act on your own behalf.

Fear is real, and you should acknowledge it. But also acknowledge you give fear its power. Feel the fear, be afraid. But don’t succumb to the power you give it.

Put yourself out there. Do it tomorrow. You won’t die. And I bet you’ll surprise others.

But I’m sure you’ll surprise yourself more.

The Ladder Of Your Own Making

There’s a natural hierarchy to work. Your job, if you choose to accept it is to climb the ladder of hierarchy rung-by-rung. Here’s how to go about it:

There’s a natural hierarchy to work. Your job, if you choose to accept it is to climb the ladder of hierarchy rung-by-rung. Here’s how to go about it:

Level 1. Work you can say no to – Say no to it. Say no effectively as you can, but say it. Saying no to level 1 work frees you up for the higher levels.

Level 2. Work you can get someone else to do – Get someone else to do it. Give the work to someone who considers the work a good reach, or a growth opportunity. This isn’t about shirking responsibility, it’s about growing young talent. Maybe you can spend a little time mentoring and the freed up time doing higher level work. Make sure you give away the credit so next time others will ask you for the opportunity to do this type of work for you.

Level 3. Work you’ve done before, but can’t wiggle out of – Do it with flair, style, and efficiency; do it differently than last time, then run away before someone asks you to do it again. Or, do it badly so next time they ask someone else to do it. Depending on the circumstance, either way can work.

Level 4. Work you haven’t done before, but can’t wiggle out of – Come up with a new recipe for this type of work, and do it so well it’s unassailable. This time your contribution is the recipe; next time your contribution is to teach it to someone else. (See level 2.)

Level 5. Work that scares others – Figure out why it scares them; break it into small bites; and take the smallest first bite (so others can’t see the failure). If it works, take a bigger bite; if it doesn’t, take a different smallest bite. Repeat, as needed. Next time, since you’ve done it before, treat it like level 3 work. Better still, treat it like level 2.

Level 6. Work that scares you – Figure out why it scares you, then follow the steps for level 5.

Level 7. Work no one knows to ask you to do – You know your subject matter better than anyone, so figure out the right work and give it a try. This flavor is difficult because it comes at the expense of work you’re already signed up to do and no one is asking you to do it. But you should have the time because you followed the guidance in the previous levels.

Level 8. Work that obsoletes the very thing that made your company successful – This is rarified air – no place for the novice. Ultimately, someone will do this work, and it might as well be you. At least you’ll be able to manage the disruption on your own terms.

In the end, your task, if you choose to accept it, is to migrate toward the work that obsoletes yourself. For only then can you start back at level 1 on the ladder of your own making.

Can It Grow?

If you’re working in a company you like, and you want it to be around in the future, you want to know if it will grow. If you’re looking to move to a new company, you want to know if it has legs – you want to know if it will grow. If you own stock, you want to know if the company will grow, and it’s the same if you want to buy stock. And it’s certainly the case if you want to buy the whole company – if it can grow, it’s worth more.

If you’re working in a company you like, and you want it to be around in the future, you want to know if it will grow. If you’re looking to move to a new company, you want to know if it has legs – you want to know if it will grow. If you own stock, you want to know if the company will grow, and it’s the same if you want to buy stock. And it’s certainly the case if you want to buy the whole company – if it can grow, it’s worth more.

To grow, a company has to differentiate itself from its competitors. In the past, continuous improvement (CI) was a differentiator, but today CI is the minimum expectation, the cost of doing business. The differentiator for growth is discontinuous improvement (DI).

With DI, there’s an unhealthy fascination with idea generation. While idea generation is important, companies aren’t short on ideas, they’re short on execution. But the one DI differentiator is the flavor of the ideas. To do DI a company needs ideas that are radically different than the ones they’re selling now. If the ideas are slightly twisted variants of today’s products and business models, that’s a sure sign continuous improvement has infiltrated and polluted the growth engine. The gears of the DI engine are gummed up and there’s no way the company can sustain growth. For objective evidence the company has the chops to generate the right ideas, look for a process that forces their thinking from the familiar, something like Jeffrey Baumgartner’s Anticonventional Thinking (ACT).

For DI-driven growth, the ability to execute is most important. With execution, the first differentiator is how the company investigates radically new ideas. There are three differentiators – a focus on speed, a “market first” approach, and the use of minimum viable tests (MVTs). With new ideas, it’s all about how fast you can learn, so speed should come through loud and clear. Without a market, the best idea is worthless, so look for “market first” thinking. Idea evaluation starts with a hypothesis that a specific market exists (the market is clearly defined in the hypothesis) which is evaluated with a minimum viable test (MVT) to prove or disprove the market’s existence. MVTs should error on the side of speed – small, localized testing. The more familiar minimum viable product (MVP) is often an important part of the market evaluation work. It’s all about learning about the market as fast as possible.

Now, with a validated market, the differentiator is how fast company can rally around the radically new idea and start the technology and product work. The companies that can’t execute slot the new project at the end of their queue and get to it when they get to it. The ones that can execute stop an existing (lower value) project and start the new project yesterday. This stop-to-start behavior is a huge differentiator.

The company’s that can’t execute take a ready-fire-aim approach – they just start. The companies that differentiate themselves use systems thinking to identify gaps in resources and capabilities and close them. They do the tough work of prioritizing one project over another and fully staff the important ones at the expense of the lesser projects. Rather than starting three projects and finishing none, the companies that know how to do DI start one, finish one, and repeat. They know with DI, there’s no partial credit for a project that’s half done.

All companies have growth plans, and at the highest level they all hang together, but some growth plans are better than others. To judge the goodness of the growth plan takes a deeper look, a look into the work itself. And once you know about the work, the real differentiator is whether the company has the chops to execute it.

Image credit – John Leach.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski