Archive for the ‘Intellectual Intertia’ Category

Less With Far Less

We don’t know the question, but the answer is innovation. And with innovation it’s more, more, more. Whether it’s more with less, or a lot more with a little more, it’s always more. It’s bigger, faster, stronger, or bust. It’s an enhancement of what is, or an extrapolation of what we have. Or it’s the best of product one added to product two. But it’s always more.

We don’t know the question, but the answer is innovation. And with innovation it’s more, more, more. Whether it’s more with less, or a lot more with a little more, it’s always more. It’s bigger, faster, stronger, or bust. It’s an enhancement of what is, or an extrapolation of what we have. Or it’s the best of product one added to product two. But it’s always more.

More-on-more makes radical shifts hard because with more-on-more we hold onto all functionality then add features, or we retain all features then multiply output. This makes it hard to let go of constraints, both the fundamental ones – which we don’t even see as constraints because they masquerade as design rules – and the little-known second class constraints – which we can see, but don’t recognize their power to block first class improvements. (Second class constraints are baggage that come with tangential features which stop us from jumping onto new S-curves for the first class stuff.)

To break the unhealthy cycle of more-on-more addition, think subtraction. Take out features and function. Distill to the essence. Decree guilty until proven innocent, and make your marketers justify the addition of every feature and function. Starting from ground zero, ask your marketers, “If the product does just one thing, what should it do?” Write it down as input to the next step.

Next, instead of more-on-more multiplication, think division. Divide by ten the minimum output of your smallest product. (The intent it to rip your engineers and marketers out of the rut that is your core product line.) With this fractional output, ask what other technologies can enable the functionality? Look down. Look to little technologies, technologies that you could have never considered at full output. Congratulations. You’ve started on your migration toward with less-with-far-less.

On the surface, less-with-far-less doesn’t seem like a big deal. And at first, folks roll their eyes at the idea of taking out features and de-rating output by ten. But its magic is real. When product performance is clipped, constraints fall by the wayside. And when the product must do far less and constraints are dismissed, engineers are pushed away from known technologies toward the unfamiliar and unreasonable. These unfamiliar technologies are unreasonably small and enable functionality with far less real estate and far less inefficiency. The result is radically reduced cost, size, and weight.

Less-with-far-less enables cost reductions so radical, new markets become viable; it makes possible size and weight reductions so radical, new levels of portability open unimaginable markets; it facilitates power reductions so radical, new solar technologies become viable.

The half-life of constraints is long, and the magic from less-with-far-less builds slowly. Before they can let go of what was, engineers must marinate in the notion of less. But when the first connections are made, a cascade of ideas follow and things spin wonderfully out of control. It becomes a frenzy of ideas so exciting, the problem becomes cooling their jets without dampening their spirit.

Less-with-far-less is not dumbed-down work – engineers are pushed to solve new problems with new technologies. Thermal problems are more severe, dimensional variation must be better controlled, and failure modes are new. In fact, less-with-far-less creates steeper learning curves and demands higher-end technologies and even adolescent technologies.

Our thinking, in the form of constraints, limits our thinking. Less-with-far-less creates the scarcity that forces us to abandon our constraints. Less-with-far-less declares our existing technologies unviable and demands new thinking. And I think that’s just what we need.

Work The Rule

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the reason for the rule is no longer, do you follow it or declare it unreasonable?

If you don’t understand the rule do you work to understand it, or conveniently trespass?

If you don’t follow the rule, does that say something about the rule, or you?

When is a rule a rule and when is it shackles?

When it comes to law, physics, and safety, a rule is a rule.

If you’re limited by the rule, is it bad? (Isn’t far worse if you don’t realize it?)

What if the solution demands unruliness?

If you don’t follow rules, is it okay to make them?

What if a culture is so strong it rules out most everything, except following the rules?

What if a culture is so strong it demands you make the rules?

When it comes to rules, there’s only one rule – You decide.

I will hold a Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Run From Your Success

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Certainly it’s impossible to worry about a competitor we’ve not met, but that’s just what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to use thought-shifting mechanisms to help us see ourselves from the framework of our unknown competitor.

Our unknown competitor doesn’t have much – no fully functional products, no fully built-out product lines, and no market share. And that’s where we must shift our thinking – to a place of scarcity – so we can see ourselves from their framework. We’ve got to look down (in the S-curve sense), sit ourselves at the bottom, and look up at our successful selves. It’s the best way to move from self-cherishing to self-dismantling.

To start, we must create our logical trajectory. First, define where we are and where we came from. Then, with a ruler aligned to the points, extend a line into the future. That’s our logical trajectory – an extrapolation in the direction of our success. Along this line we will do more of what got us here, more of what we’ve done. Without giving ground on any front, we will protect market share and build more. We’ve now defined how we see ourselves. We’ve now defined the thinking that could be our undoing.

Now we must force enlightenment on ourselves. We create an illogical trajectory where we see ourselves from a success-less framework. In this framework less is more; more-of-the-same is displaced with more-of-something-else; and success is a weakness. We know we’re sitting in the rights space when the smallest slice of incremental market share looks like a big, juicy bite – like it looks to our unknown competitor.

The disruptive technology created by our unknown competitor will start innocently. Immature at first, the disruptive technology will do most things poorly but do one thing better. Viewed from our success framework we will see only limitations and dismiss it, while our unknown competitors will see opportunity. We will see the does-most-things-poorly part and they’ll see the one-thing-better part. They will sell to a small segment that values the one-thing-better part.

In another variant, an immature disruptive technology will do less with far less. From our success framework we will see “less” while from their scarcity framework they will see “more”. They will sell a simpler product that does less for a price that’s far less. (And make money.)

Here’s the one that’s most frightening: an immature technology that does all things poorly but does them without a fundamental limitation of our technology. From our framework the limitation is so fundamental we won’t let ourselves see it. This limitation is un-seeable because we’ve built our business around it. (Think Kodak film.) This flavor of disruptive technology can put our business model out of business, yet we’ll dismiss it.

We’ll know we’ve shifted our thinking to the right place when we see our unknown competitors not as bottom-feeders but as hungry competitors who see our scraps as a smorgasbord.

We’ll know our thinking’s right when see not self-destruction, but self-disruption.

We’ll know all is right with the world we’re working on disruptive technologies to disrupt ourselves, disruptive technologies with the potential to create business models so compelling that we’ll gladly run from our success.

Be Your Stiffest Competitor

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Your business is going away. Not if, when. Someone’s going to make it go away and it might as well be you. Why not take control and make it go away on your own terms? Why not make it go away and replace it with something bigger and better?

Success is good, but fleeting. Like a roller coaster with up-and-up clicking and clacking, there’s a drop coming. But with a roller coaster we expect it – there’s always a drop. (That’s what makes it a roller coaster.) We get ready for it, we brace ourselves. Half-scared and half-excited, electricity fills us, self-made fight-or-flight energy that keeps us safe. I think success should be the same – we should expect the drop.

More strongly we should manage the drop, make it happen on our terms. But that’s going to be difficult. Success makes it easy to unknowingly slip into protecting-what-we-have mode. If we’re to manage the drop, we must learn to relish it like the roller coaster. As we’re ascending – on the way up – we must learn to create a healthy discomfort around success, like the sweaty-palm feeling of the roller coaster’s impending wild ride.

A sky-is-falling approach won’t help us embrace the drop. With success all around, even the best roller coaster argument will be overpowered. The argument must be based on positivity. Acknowledge success, celebrate it, and then challenge your organization to improve on it. Help your organization see today’s success as the foundation for the future’s success – like standing on the shoulders of giants. But in this case, the next level of success will be achieved by dismantling what you’ve built.

No one knows what the future will be, other than there will be increased competition. Hopefully, in the future, your stiffest competitor will be you.

Seeing Things As They Are

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

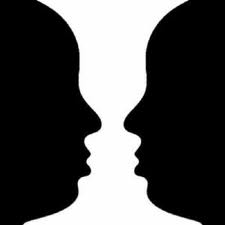

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

Organizationally Challenged – Engineering and Manufacturing

Our organizations are set up in silos, and we’re measured that way. (And we wonder why we get local optimization.) At the top of engineering is the VP of the Red Team, who is judged on what it does – product. At the top of manufacturing is the VP of the Blue Team, who is judged on how to make it – process. Red is optimized within Red and same for Blue, sometimes with competing metrics. What we need is Purple behavior.

Here’s a link to a short video (1:14): Organizationally Challenged

And embedded below:

Let me know what you think.

Amplify The Social Benefits of Your Products

To do g ood for the planet and make lots of money (or the other way around), I think companies should shift from an economic framework to a social one. Green products are a good example. Facts are facts: today, as we define cost, green products cost more; burning fossil fuel is the lowest cost way to produce electricity and move stuff around (people, products, raw material). Green products are more expensive and do less, yet they sell. But the economic benefits don’t sell, the social ones do. Lower performance and higher costs of green products should be viewed not as weaknesses, but as strengths.

ood for the planet and make lots of money (or the other way around), I think companies should shift from an economic framework to a social one. Green products are a good example. Facts are facts: today, as we define cost, green products cost more; burning fossil fuel is the lowest cost way to produce electricity and move stuff around (people, products, raw material). Green products are more expensive and do less, yet they sell. But the economic benefits don’t sell, the social ones do. Lower performance and higher costs of green products should be viewed not as weaknesses, but as strengths.

Green technologies are immature and expensive, but there’s no questions they’re the future. Green products will create new markets, and companies that create new markets will dominate them. The first sales of expensive green products are made by those who can afford them; they put their money where their mouths are and pay more for less to make a social statement. In that way, the shortcoming of the product amplifies the social statement. It’s clear the product was purchased for the good of others, not solely for the goodness of the product itself. The sentiment goes like this: This product is more expensive, but I think the planet is worth my investment. I’m going to buy, and feel good doing it.

The Prius is a good example. While its environmental benefits can be debated, it clearly does not drive as well as other cars (handling, acceleration, breaking). Yet people buy them. People buy them because that funny shape is mapped to a social statement: I care about the environment. Prius generates a signal: I care enough about the planet to put my money where my mouth is. It’s a social statement. I propose companies use a similar social framework to create new markets with green products that do less, cost more, and overtly signal their undeniable social benefit. (To be clear, the product should undeniably make the planet happy.)

The company that creates a new market owns it. (At least it’s theirs to lose). Early sales impregnate the brand with the green product’s important social statement, and the new market becomes the brand and its social statement. And more than that, early sales enable the company to work out the bugs, allow the technology to mature, and yield lower costs. Lower costs enable a cost effective market build-out.

Don’t shy away from performance gaps of green technologies, embrace them; acknowledge them to amplify the social benefit. Don’t shy away from a high price, embrace it; acknowledge the investment to amplify the social benefit. Be truthful about performance gaps, price it high, and proudly do good for the planet.

Make your green programs actionable

There’s a big push to be green. Though we want to be green, we’re not sure how to get there. We’ve got high-level metrics, but they’re not actionable. It’s time to figure out what we can change to be green.

There’s a big push to be green. Though we want to be green, we’re not sure how to get there. We’ve got high-level metrics, but they’re not actionable. It’s time to figure out what we can change to be green.

One way manufacturers can be green is to reduce their carbon footprint. That’s one level deeper than simply “being green,” but it’s not actionable either. Digging deeper, manufacturers can reduce their carbon footprint by generating less greenhouse gases, specifically carbon dioxide. Reducing carbon dioxide production is a good goal, but it’s still not actionable.

Looking deeper, carbon dioxide is the result of burning fossil fuels,

The Power of Now

I think we underestimate the power of now, and I think we waste too much emotional energy on the past and future.

I think we underestimate the power of now, and I think we waste too much emotional energy on the past and future.

We use the past to create self-inflicted paralysis, to rationalize inaction. We dissect our failures to avoid future missteps, and push progress into the future. We make no progress in the now. This is wrong on so many levels.

In all written history there has never been a mistake-free endeavor. Never. Failure is part of it. Always. And learning from past failures is limited because the situation is different now: the players are different, the technology is different, the market is different, and the problems are different. We will make new mistakes, unpredictable mistakes. Grounding ourselves in the past can only prepare us for the previous war, not the next one.

Like with the past, we use the future’s uncertainty to rationalize inaction, and push action into the future. The future has not happened yet so by definition it’s uncertain. Get used to it. Embrace it. I’m all for planning, but I’m a bigger fan of doing, even at the expense of being wrong. Our first course heading is wrong, but that doesn’t mean the ship doesn’t sail. The ship sales and we routinely checks the heading, regularly consults the maps, and constantly monitors the weather. Living in the now, it’s always the opportunity for a course change, a decision, or an action.

The past is built on old thinking, and it’s unchangeable – let it go. Spend more emotional energy on the now. The future is unpredictable an uncontrollable, and it’s a result of decisions made in the now – let it go. Spend more energy on the now.

It’s tough to appreciate the power of now, and maybe tougher to describe, but I’ll take a crack at it. When we appreciate the power of now we have a bias for action; we let go of the past; we speculate on the future and make decisions with less than perfect information; and we constantly evaluate our course heading.

Give it a try. Now.

Marinate yourself in scarcity to create new thinking

There’s agreement: new thinking is needed for innovation. And for those that have tried, there’s agreement that it’s hard. It’s hard to create new thinking, to let go of what is, to see the same old things as new, to see resources where others see nothing. But there are some tricks to force new thinking, to help squeeze it out of ourselves.

There’s agreement: new thinking is needed for innovation. And for those that have tried, there’s agreement that it’s hard. It’s hard to create new thinking, to let go of what is, to see the same old things as new, to see resources where others see nothing. But there are some tricks to force new thinking, to help squeeze it out of ourselves.

The answer, in a word, is scarcity.

In the developing world there is scarcity of everything: food, shelter, electricity, tools, education; in the developed world we must fabricate it. We must dust off the long-neglected thought experiment, and sit ourselves in self-made scarcity.

Try a thought experiment that creates scarcity in time. Get the band together and ask them this question: If you had only two weeks to develop the next generation product, what would you do? When they say the question is ridiculous, agree with them. Tell them that’s the point. When they try to distract and derail, hold them to it. Don’t let them off the hook. Scarcity in time will force them to look at everything as a resource, even the user and the environment itself (sunlight, air, wind, gravity, time), or even trash or byproduct from something in the vicinity. At first pass, these misused resources may seem limited, but with deeper inspection, they may turn out to be better than the ones used today. The band will surprise themselves with what they come up with.

Next, try a thought experiment that creates scarcity of goodness. Get the band back together, and take away the major performance attribute of your product (the very reason customers buy); decree the new product must perform poorly. If fast is better, the new one must be slow; if stiff is better, the new one must be floppy; if big, think small. This forces the band to see strength as weakness, forces them to identify and release implicit constraints that have never been named. Once the bizarro-world product takes shape, the group will have a wonderful set of new ideas. (The new product won’t perform poorly, it will have novel functionality based on the twisted reality of the thought experiment.)

Innovation requires new thinking, and new thinking is easier when there’s scarcity – no constraints, no benchmarks, no core to preserve and protect. But without real scarcity, it’s difficult to think that way. Use the time-tested thought experiment to marinate yourself in scarcity, and see what comes of it.

For innovation, look inside.

Everyone is dissatisfied with the pace of innovation – solutions that change the game don’t come fast enough. We look to the environment, and assign blame. We blame the tools, the process, the organization structure, and the technology itself. But the blame is misplaced. It is the innovators that govern the pace of innovation.

Everyone is dissatisfied with the pace of innovation – solutions that change the game don’t come fast enough. We look to the environment, and assign blame. We blame the tools, the process, the organization structure, and the technology itself. But the blame is misplaced. It is the innovators that govern the pace of innovation.

It certainly isn’t the technology – the solutions already exist; they’re patiently waiting for us, waiting for us to find them. We just have to look. The technology knows what it will be when it grows up: the path is clear. Put simply, we must break through our unwillingness to look. We must look harder, deeper, and more often. We must redefine our self-set limits, and look under the rocks of our successes and beyond our best work.

To increase the pace and quality of innovation, we must look inside.

a

a

p.s. I’m holding a half-day workshop on how to implement systematic cost savings through product design on June 13 in Providence RI as part of the International Forum on DFMA — here’s the link. I hope to see you there.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski