Archive for the ‘Intellectual Intertia’ Category

A Unifying Theory for Manufacturing?

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

The notion of a unifying theory is tantalizing – one idea that cuts across everything. Though there isn’t one in manufacturing, I think there’s something close: Design simplification through part count reduction. It cuts across everything – across-the-board simplification. It makes everything better. Take a look how even HR is simplified.

HR takes care of the people side of the business and fewer parts means fewer people – fewer manufacturing people to make the product, fewer people to maintain smaller factories, fewer people to maintain fewer machine tools, fewer resources to move fewer parts, fewer folks to develop and manage fewer suppliers, fewer quality professionals to check the fewer parts and create fewer quality plans, fewer people to create manufacturing documentation, fewer coordinators to process fewer engineering changes, fewer RMA technicians to handle fewer returned parts, fewer field service technicians to service more reliable products, fewer design engineers to design fewer parts, few reliability engineers to test fewer parts, fewer accountants to account for fewer line items, fewer managers to manage fewer people.

Before I catch hell for the fewer-people-across-the-board language, product simplification is not about reducing people. (Fewer, fewer, fewer was just a good way to make a point.) In fact, design simplification is a growth strategy – more output with the people you have, which creates a lower cost structure, more profits, and new hires.

A unifying theory? Really? Product simplification?

Your products fundamentally shape your organization. Don’t believe me? Take a look at your businesses – you’ll see your product families in your org structure. Take look at your teams – you’ll see your BOM structure in your org structure. Simplify your product to simplify your company across-the-board. Strange, but true. Give it a try. I dare you.

Our fear is limiting DoD’s Affordability Quest

The DoD wants to save money, but they can’t do it alone. But can they possibly succeed? Do they have fighting a chance? Can they get it done? Wrong pronouns.

The DoD wants to save money, but they can’t do it alone. But can they possibly succeed? Do they have fighting a chance? Can they get it done? Wrong pronouns.

Can we possibly succeed?

Do we have a fighting chance?

Can we get it done?

In difficult times it’s easy to be critical of others, to make excuses, to look outside. (They, they, they.) In difficult times it’s hard find the level 5 courage to be critical ourselves, to take responsibility, to look inside. (We, we, we.) But we must look inside because that’s where the answer is. We know our work best; we’re the only ones who can reinvent our work; we’re the ones who can save money; we’re responsible.

Changing our actions, our work, is scary, but that’s what the DoD is asking for; we must overcome our fear. But to overcome it we must acknowledge it, see it as it is, and work through it.

Here’s the DoD’s challenge: “Contractors – provide us more affordable systems.” There are two ways we can respond.

The fear-based response (the they response): The DoD won’t accept the changes. In fact, they’ve never liked change. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The seeing things as they are response (the we response): We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know what changes to propose, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The they response: Their MIL specs dictate the design and they won’t budge on them. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The we response: We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know why we designed it that way, we don’t know all that much about the design, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The they response: All they care about is performance. They are driving the complexity. And when push comes to shove, they don’t care about cost. They’ll say no to any changes. They always have.

The we response: We must try, since not trying is the only way to guarantee failure. Things are different now. Change is acceptable. However, the facts are we don’t know what truly controls performance, we don’t know what we can change, we don’t know the sensitivities, we don’t know what creates cost, and we don’t know how to design low cost, low complexity systems. We were never taught. We need to develop our capability if we’re to be successful.

The DoD has courageously told us they want to overcome their fear. Let’s follow their lead and overcome ours. It will be good for everyone.

DoD’s Affordability Eyeball

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

…we have a continuing responsibility to procure the critical goods and services our forces need in the years ahead, but we will not have ever-increasing budgets to pay for them.

And, we must

DO MORE WITHOUT MORE.

I like it.

Of the DoD’s $700B yearly spend, $200B is spent on weapons, electronics, fuel, facilities, etc. and $200B on services. Carter lays out themes to reduce both flavors. On services, he plainly states that the DoD must put in place systems and processes. They’re largely missing. On weapons, electronics, etc., he lays out some good themes: rationalization of the portfolio, economical product rates, shorter program timelines, adjusted progress payments, and promotion of competition. I like those. However, his Affordability Mandate misses the mark.

Though his Affordability Mandate is the right idea, it’s steeped in the wrong mindset, steeped in emotional constraints that will limit success. Take a look at his language. He will require an affordability target at program start (Milestone A)

to be treated like a Key Performance Parameter (KPP) such as speed or power – a design parameter not to be sacrificed or comprised without my specific authority.

Implicit in his language is an assumption that performance will decrease with decreasing cost. More than that, he expects to approve cost reductions that actually sacrifice performance. (Only he can approve those.) Sadly, he’s been conditioned to believe it’s impossible to increase performance while decreasing cost. And because he does not believe it, he won’t ask for it, nor get it. I’m sure he’d be pissed if he knew the real deal.

The reality: The stuff he buys is radically over-designed, radically over-complex, and radically cost-bloated. Even without fancy engineering, significant cost reductions are possible. Figure out where the cost is and design it out. And the lower cost, lower complexity designs will work better (fewer things to break and fewer things to hose up in manufacturing). Couple that with strong engineering and improved analytical tools and cost reductions of 50% are likely. (Oh yes, and a nice side benefit of improved performance). That’s right, 50% cost reduction.

Look again at his language. At Milestone B, when a system’s detailed design is begun,

I will require a presentation of a systems engineering tradeoff analysis showing how cost varies as the major design parameters and time to complete are varied. This analysis would allow decisions to be made about how the system could be made less expensive without the loss of important capability.

Even after Milestone A’s batch of sacrificed of capability, at Milestone B he still expects to trade off more capability (albeit the lesser important kind) for cost reduction. Wrong mindset. At Milestone B, when engineers better understand their designs, he should expect another step function increase in performance and another step function decrease of cost. But, since he’s been conditioned to believe otherwise, he won’t ask for it. He’ll be pissed when he realizes what he’s leaving on the table.

For generations, DoD has asked contractors to improve performance without the least consideration of cost. Guess what they got? Exactly what they asked for – ultra-high performance with ultra-ultra-high cost. It’s a target rich environment. And, sadly, DoD has conditioned itself to believe increased performance must come with increased cost.

Carter is a sharp guy. No doubt. Anyone smart enough to reduce nuclear weapons has my admiration. (Thanks, Ash, for that work.) And if he’s smart enough to figure out the missile thing, he’s smart enough to figure out his contractors can increase performance and radically reduces costs at the same time. Just a matter of time.

There are two ways it could go: He could tell contractors how to do it or they could show him how it’s done. I know which one will feel better, but which will be better for business?

Do you know?

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

When we know we know – we understand fundamentals, we have a model, we have evidence, we can predict. We can build on this knowledge. We’re not often in this state, but it sure feels good when we are. The trick here is to understand the applicability of the knowledge. Change the inputs, change the system, or change the environment and we must question our knowledge. Do the fundamentals still apply?

When we don’t know – no fundamentals, no model, and no predictions. No danger on building on bad knowledge. Life is uncomplicated. Next task: develop the fundamentals; build a model. We’re in this state more often than we admit, and there’s the danger. It’s politically difficult to say “I don’t know.” But it must be said. Otherwise we’re expected to predict the future and to build on the knowledge (that we don’t have).

When we think we know – no fundamentals, no model, and predictions we bet our businesses on. Danger. It feels just as good as when we know we know, but it shouldn’t. Momentum in the wrong direction and we don’t know it. And we’re likely in this state more often than not. But this is a meta-state, an unstable state. The trick is to push on our knowledge so we tip into one of the other two states. Push on our knowledge so we know if we know.

Do you know the fundamentals? Do you have a model? Can you predict?

Green Jeans Drive Innovation

Environmental stability, aka, Green, is just starting. Most are still in reluctant compliance mode, hoping beyond hope that this newest of corporate initiatives dies on the vine, that it’s just another corporate initiative. Wrong. Very wrong. It’s the way we’re going to grow our business; it’s the way we’re going to make money. It’s time to open our minds, grab Green by the throat, and shake it. Green is here to stay, and Green will demand we change our thinking, will make us see our problems differently, will require we dismantle our intellectual inertia, will require innovation.

Environmental stability, aka, Green, is just starting. Most are still in reluctant compliance mode, hoping beyond hope that this newest of corporate initiatives dies on the vine, that it’s just another corporate initiative. Wrong. Very wrong. It’s the way we’re going to grow our business; it’s the way we’re going to make money. It’s time to open our minds, grab Green by the throat, and shake it. Green is here to stay, and Green will demand we change our thinking, will make us see our problems differently, will require we dismantle our intellectual inertia, will require innovation.

Pretend you’re a manufacturer of jeans, the blue ones, the ones that feel so good when you put them on, the ones you’d like to wear to work if you could. (Maybe that’s just me.) Year-on-year your innovation efforts focus on adding pockets then removing them, adding holes then removing them, zippers here then there, dark wash then light, baggy then tight, and yellow stitching than red. What else can a jean innovator do?

Corporate sends the memo: “We’re going Green.” Green jeans. They hire the best sustainability consultants and you, the jean innovator, sit through the sustainability audit results. Their recommendation – reduce carbon footprint: use materials that consume less energy, reduce electricity in your factories, minimize distribution’s fuel costs, and reduce travel miles of your sales folks. Brilliant. Whatever we paid these guys, it was too much. But then they twist your brain. The carbon footprint from the use of your product dwarfs everything else. Your customers generate a massive carbon footprint when they wash and dry your jeans, and you have no control over it. Your jeans are made once and washed and dried countless times. Whoa. Your eyes roll back in your head. What’s a jean innovator to do? First thing – forget about the stupid pockets. Next, figure out how to reduce the carbon footprint generated by your customers. Define the problem and innovate. But what’s the problem?

Why do folks wash their jeans? The obvious answer – they’re dirty. Let’s figure a way to prevent jeans from getting dirty, right? No. The real answer – they stretch, they get baggy and don’t fit right; so we wash them to tighten things up. We wash CLEAN jeans because they get baggy, not because they’re dirty. Let’s fix that.

Believe it or not, there are many likely innovative solutions to make jeans de-baggy themselves, but that’s not the point. The point is we must innovate on jeans that reconfigure, and must not innovate on keeping jeans clean (though we may innovate on that down the road) and must not innovate on pockets, zippers, and stitching.

Green shaped our innovation work. We now have Green jeans that feel good and spring back after wearing and fit great on day two – no washing required. We now have Green jeans that save customers time and money while flattering their backside. But here’s the point – we would have never invented de-baggying jeans without opening our minds to Green as a way to grow our business, to Green as a way to make money. Reluctant compliance won’t get us there. Grab Green by the throat and shake it…before your competitors do.

Who killed Vacation?

What happened to Vacation? It used to be a time to let go, to separate from work, to engage with family and friends, to work hard on something else. A time to refresh, to recharge, to renew. Not anymore – a shadow of its former self – paler, thinner, hunched over.

What happened to Vacation? It used to be a time to let go, to separate from work, to engage with family and friends, to work hard on something else. A time to refresh, to recharge, to renew. Not anymore – a shadow of its former self – paler, thinner, hunched over.

We still stay out of the office in a physical sense, but not in a virtual one. Our butts may be “on vacation” in that we sit someplace else, but our brains are not. They’re still fully invested in office things, running in the background as our butts enjoy their vacation. We’ve got all the downside of being out of the office with none of the upside. It’s almost worse than not having vacation. At least we don’t fall behind when not on vacation.

Who’s to blame? The technology? Our company? I don’t think so. We are. Sure the technology makes it easy: cell coverage across the globe (accept in New Hampshire), fast connections, nice screens, and full thumb keyboards to crank out the email. But, if I’m not mistaken, those little pda bastards still have an off switch. If your thumb can pound the keys, it can certainly mash the off switch. Can’t shut the damn thing off because you want to respond to the emergency work call? That’s crap. Work emergencies don’t exist, they’re artificial, self-made. We create them to increase the sense of urgency. Don’t buy that? Here’s another rationale: you’re not giving others the opportunity to think while you’re gone. You’re telling them they’re not capable of thinking for themselves, you’re dismantling their self esteem, and hindering their growth.

Our company? Sure, they make it hard to let go, with implications that important projects must run seamlessly, that the ball must still be advanced. But, we’re the ones who decide what our brains think about. We must decide to give others an opportunity to shine, to give away the responsibility to someone who can likely do it better. If you ask the company what they want when we return, they’ll say they want us to come back recharged, ready to see things differently, ready to be creative, ready to be authentic. You cannot be that person without letting go. Without letting go, you’ll return the same worn soul who can but raft downstream with the current instead of swimming violently against it.

Take responsibility for your vacation. Own it, tell others you own it. Tell them you’re serious about letting go, working hard on something else, recharging. Use the all powerful Out of Office AutoReply as it was intended, to set everyone’s expectations explicitly (including your own).

Out of Office AutoReply: I am on vacation.

The Emotional Constraint

“Constraint” is most often an excuse rather than a constraint. In fact, there are very few true constraints, with most of them living in the domain of physics.

“Constraint” is most often an excuse rather than a constraint. In fact, there are very few true constraints, with most of them living in the domain of physics.

A constraint is when something cannot be done. It’s not when something is difficult, complex, or unknown. And, it’s not when the options are costly, big, or ugly. There are no options with a true constraint. Nothing you can do.

The Physical Constraint

If your new product requires one of its moving parts to go faster than the speed of light, that’s a physical constraint (and not a good idea). If your new technology requires a material that’s stronger than the strongest on record, that’s a constraint (and, also, not a good idea). If your new manufacturing process consumes more water than your continent can spare, that’s a constraint. (This may not be a true constraint in the physics sense, but it’s damn close.) Don’t try to overpower the physical constraint – you can’t beat Mother Nature. The best you can do is wrestle her to a tie, then, when you tire, she pins you.

The Legal Constraint

If your approach violates a law, that’s a legal constraint. Not a true constraint in a physical sense, as there are options. You can change your approach so the law is not violated (maybe to a more costly approach), you can lobby for a law change (may take a while, but it’s an option), or you can break the law and roll the dice. To be clear, I don’t recommend this, just wanted to point out that there are options. Options exist when something is not a constraint, though the consequences can be most undesirable, severe, and may not fit with who we are.

The Emotional Constraint

If a person in power self-declares something as a constraint, decides there are no options, that’s an emotional constraint. Not a true constraint in a physical sense, but it’s the most dangerous of the triad. When there is no balance in the balance of power, or the consequences of pushing are severe, the self-declared emotional constraint stands – there are no options. Like with the speed of light, where adding energy cannot overcome the speed constraint, adding reasoning energy cannot overcome the emotional constraint. I argue that most constraints are emotional.

Physical and legal constraints are relatively easy to see and navigate, but the emotional constraint is something different altogether. Difficult to see, difficult to predict, and difficult to overcome. Person-based rather than physics or law-based.

Strategies to overcome emotional constraints must be based on the particulars of the person declaring the constraint. However, there is one truism to all successful strategies: Just as the person in power is the only one who can convince himself something is a constraint, he is also the only one who can convince himself otherwise.

What comes first, the procedure or the behavior?

It’s the chicken-and-egg syndrome of the business world. Does procedure drive behavior or does behavior drive procedure?

It’s the chicken-and-egg syndrome of the business world. Does procedure drive behavior or does behavior drive procedure?

Procedures are good for documenting a repetitive activity:

- Pick up that part.

- Grab that wrench.

- Tighten that nut.

- Repeat, as required.

This type of procedure has value – do the activity in the prescribed way and the outcome is a high quality product. But what if the activity is new? What if judgment and thinking govern the major steps? What if you don’t know the steps? What if there is no right answer? What does that procedure look like?

Try to modify an existing procedure to fit an activity your company has not yet done. Better yet, try to write a new one. It’s easy to write a procedure after-the-fact. Just look back at what you did and make a flow chart. But what about a procedure for an activity that does not exist? For an old activity done in a future new way? Does the old procedure tell you the new way? Just the opposite. The old procedure tells you cannot do anything differently. (That’s why it’s called a procedure). Do what you did last time, or fail the audit. Be compliant. Standardize on the old way, but expect new and better results.

Here is a draft of a procedure for new activities:

- Call a meeting with your best people.

- Ask them to figure out a new way.

- Give them what they ask for.

- Get out of the way, as required.

When they succeed, lather on the praise and positivity. It will feel good to everyone. Create a procedure after-the-fact if you wish. But, no worries, your best people won’t limit themselves by the procedure. In fact, the best ones won’t even read it.

DFMA Won’t Work

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

Ask a company or team to do DFMA, and you get a great list of excuses on why DFMA is not applicable and won’t work. Product volumes are too low for DFMA, or too high; product costs are too low, or too high; production processes are too simple, or complex; production mix is too low, or too high. That’s all crap – just excuses to get out of doing the work. DFMA is applicable; it’s just a question of how to prioritize the work.

To prioritize the work, take a look at product volumes. They’ll put you in the right ballpark. Here are three categories, low, medium, and high volume:

Blind To Your Own Assumptions

Whether inventing new technologies, designing new products, or solving manufacturing problems, it’s important to understand assumptions. Assumptions shape the technical approach and focus thinking on what is considered (assumed) most important. Blindness to assumptions is all around us and is a real reason for concern. And the kicker, the most dangerous ones are also the most difficult to see – your own assumptions. What techniques or processes can we use to ferret out our own implicit assumptions?

Whether inventing new technologies, designing new products, or solving manufacturing problems, it’s important to understand assumptions. Assumptions shape the technical approach and focus thinking on what is considered (assumed) most important. Blindness to assumptions is all around us and is a real reason for concern. And the kicker, the most dangerous ones are also the most difficult to see – your own assumptions. What techniques or processes can we use to ferret out our own implicit assumptions?

By definition, implicit assumptions are made without formalization, they’re not explicit. Unknowingly, fertile design space can be walled off. Like the archeologist digging on the wrong side of they pyramid, dig all he wants, he won’t find the treasure because it isn’t there. Also with implicit assumptions, precious time and energy can be wasted solving the wrong problem. Like the auto mechanic who replaced the wrong part, the real problem remains. Both scenarios can create severe consequences for a product development project. (NOTE: the notion of implicit assumptions is closely related to the notion of intellectual inertia. See Categories – Intellectual Inertia for a detailed treatment.)

Now the tough part. How to identify your own implicit assumptions? When at their best, the halves of our brains play nicely together, but never does either side rise to the level of omnipotence. It’s impossible to stand outside ourselves and watch us make implicit assumptions. We don’t work that way. We need some techniques.

Narrow, narrow, narrow. The probability of making implicit assumptions decreases when the conflict domain is narrowed.

Narrow in space and time to make the conflict domain small and assumptions are reduced.

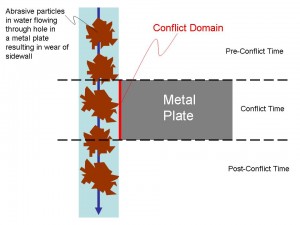

Narrow the conflict domain in space – narrow to two elements of the design that aren’t getting along. Not three elements – that’s one too many, but two. Narrow further and make sure the two conflicting elements are in direct physical contact, with nothing in between. Narrow further and define where they touch. Get small, really small, so small the direct contact is all you see. Narrowing in space reduces space-based assumptions.

Narrow the conflict domain in time – break it into three time domains: pre-conflict time, conflict time, post-conflict time. This is a foreign idea, but a powerful one. Solutions are different in the three time domains. The conflict can be prevented before it happens in the pre-conflict time, conflict can be dealt with while it’s happening (usually a short time) in the conflict time, and ramifications of the conflict can be cleaned up in the post-conflict time. Narrowing in time reduces time-based assumptions.

Assumptions narrow even further when the conflict domain is narrowed in time and space together, limiting them to the where and when of the conflict. Like the intersection of two overlapping circles, the conflict domain is sharply narrowed at the intersection of space and time – a small space over a short time.

It’s best to create a picture of the conflict domain to understand it in space and time. Below (click to enlarge) is an example where abrasives (brown) in a stream of water (light blue) flow through a hole in a metal plate (gray) creating wear of the sidewall (in red). Pre-conflict time is before the abrasive particles enter the hole from the top; conflict time is while the particles contact the sidewall (conflict domain in red); post-conflict time is after the particles leave the hole. Only the right side of the metal place is shown to focus on the conflict domain. There is no conflict where the abrasive particles do not touch the sidewall.

Even if your radar is up and running, assumptions are tough to see – they’re translucent at best. But the techniques can help, though they’re difficult and uncomfortable, especially at first. But that’s the point. The techniques force you to argue with yourself over what you know and what you think you know. For a good start, try identify the two elements of the design that are not getting along, and make sure they’re in direct physical contact. If you’re looking for more of a challenge, try to draw a picture of the conflict domain. Your assumptions don’t stand a chance.

Tools for innovation and breaking intellectual inertia

Everyone wants growth – but how? We know innovation is a key to growth, but how do we do it? Be creative, break the rules, think out of the box, think real hard, innovate. Those words don’t help me. What do I do differently after hearing them?

Everyone wants growth – but how? We know innovation is a key to growth, but how do we do it? Be creative, break the rules, think out of the box, think real hard, innovate. Those words don’t help me. What do I do differently after hearing them?

I am a process person, processes help me. Why not use a process to improve innovation? Try this: set up a meeting with your best innovators and use “process” and “innovation” in the same sentence. They’ll laugh you off as someone that doesn’t know the front of a cat from the back. Take your time to regroup after their snide comments and go back to your innovators. This time tell them how manufacturing has greatly improved productivity and quality using formalized processes. List them – lean, Six Sigma, DFSS, and DFMA. I’m sure they’ll recognize some of the letters. Now tell them you think a formalized process can improve innovation productivity and quality. After the vapor lock and brain cramp subsides, tell them there is a proven process for improved innovation.

A process for innovation? Is this guy for real? Innovation cannot be taught or represented by a process. Innovation requires individuality of thinking. It’s a given right of innovators to approach it as they wish, kind of like freedom of speech where any encroachment on freedom is a slippery slope to censorship and stifled thinking. A process restricts, it standardizes, it squeezes out creativity and reduces individual self worth. People are either born with the capability to innovate, or they are not. While I agree that some are better than others at creating new ideas, innovation does not have to be governed by hunch, experience and trial and error. Innovation does not have to be like buying lottery tickets. I have personal experience using a good process to help stack the odds in my favor and help me do better innovation. One important function of the innovation process is to break intellectual inertia.

Intellectual inertia must be overcome if real, meaningful innovation is to come about. When intellectual inertia reigns, yesterday’s thinking carries the day. Yesterday’s thinking has the momentum of a steam train puffing and bellowing down the tracks. This old train of thought can only follow a single path – the worn tracks of yesteryear, and few things are powerful enough to derail it. To misquote Einstein:

The thinking that got us into this mess is not the thinking that gets us out of it.

The notion of intellectual inertia is the opposite of Einstein’s thinking. The intellectual inertia mantra: the thinking that worked before is the thinking that will work again. But how to break the inertia? Read the rest of this entry »

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski