Archive for the ‘Innovation’ Category

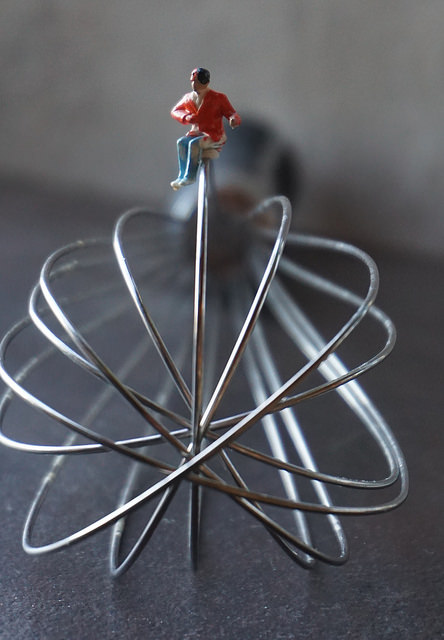

What’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

Disruption, as a word, doesn’t tell us what to do or how to do it. Disruption, as a word, it’s not helpful and should be struck from the innovation lexicon. But without the word, what’s an innovator to do?

If you have a superpower, misuse it. Your brand’s special capability is well known in your industry, but not in others. Thrust your uniqueness into an unsuspecting industry and provide novel value in novel ways. Take it by storm. Contradict the established players. Build momentum quickly and quietly. Create a step function improvement. Create new lines of customer goodness. Do things that haven’t been done. Turn no to yes.

Don’t adapt your special capability, use it as-is. Adaptation is good, but it’s better to flop the whole thing into the new space. Don’t think graft, think transplant. Adaptation brings only continuous improvement. It’s better to serve up your secret sauce uncut and unfiltered because that brings discontinuous improvement.

Know the needs your product fulfills and meet those needs in another industry. Some say it’s better to adapt your product to other industries, and to achieve a reasonable CAGR, adaptation is good. But if you’re looking for an unreasonable CAGR, if you’re looking to stand things on their head, try to use your product as-is. When you can use your product as-is in another industry, you connect dots only you can connect and meet needs in ways only you can. You bring non-intuitive solutions. You violate routines of accepted practice and your trajectory is not limited by the incumbents’ ruts of success. You’ll have a whole new space for yourself. No sharing required.

But how?

Simply and succinctly, define what your product does. Then, make it generic and look to misapply the goodness in a different application. For example, manufacturers of large and expensive furniture wrap their products in huge plastic bags to keep the furniture dry and clean during shipping. Generically, the function becomes: use large plastic bags to temporarily protect large and expensive products from becoming wet. Using that goodness in a new application, people who live in flood areas use the large furniture bags to temporarily protect their cars from water damage. Just before the flood arrives, they drive their cars into large plastic bags and tie them off. The bags keep their car dry when the water comes. Same bag, same goodness, completely unrelated application.

And there’s another way. Your product has a primary function that provides value to your customers. But, there is unrealized value in your product that your existing customers don’t value. For example, if your company has a proprietary process to paint products in a way that results in a high gloss finish, your customers buy your coating because it looks good. But, the coating may also create a hard layer and increase wear resistance that could be important in another application. Because your coating is environmentally friendly and your process is low-cost, new customers may want you to coat their parts so they can be used in a previously non-viable application. There is unrealized value in your products that new customers will pay for.

To see the unrealized value, use the strength-as-a-weakness method. Define two constraints: you must sell to new customers in a new industry and the primary goodness, why people buy your product, must be a weakness. For example, if your product is fast, you’ve got to use unrealized value to sell a slow one. If it’s heavy, the new one must be light. If small, the new one must be large. In that way, you are forced to rely on new lines of goodness and unrealized value to sell your product.

Don’t stop continuous improvement and product adaptation. They’re valuable. But, start some discontinuous improvement, step function increases and purposeful misuse. Keep selling to the same value to the same customers, but start selling to new customers with previously unrealized value that has been hiding quietly in your product for years.

Evolution is good, but exaptation is probably better.

Image credit – Sor Betto

How To Reduce Innovation Risk

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

The trouble with innovation is it’s risky. Sure, the upside is nice (increased sales), but the downside (it doesn’t work) is distasteful. Everyone is looking for the magic pill to change the risk-reward ratio of innovation, but there is no pill. Though there are some things you can do to tip the scale in your favor.

All problems are business problems. Problem solving is the key to innovation, and all problems are business problems. And as companies embrace the triple bottom line philosophy, where they strive to make progress in three areas – environmental, social and financial, there’s a clear framework to define business problems.

Start with a business objective. It’s best to define a business problem in terms of a shortcoming in business results. And the holy grail of business objectives is the growth objective. No one wants to be the obstacle, but, more importantly, everyone is happy to align their career with closing the gap in the growth objective. In that way, if solving a problem is directly linked to achieving the growth objective, it will get solved.

Sell more. The best way to achieve the growth objective is to sell more. Bottom line savings won’t get you there. You need the sizzle of the top line. When solving a problem is linked to selling more, it will get solved.

Customers are the only people that buy things. If you want to sell more, you’ve got to sell it to customers. And customers buy novel usefulness. When solving a problem creates novel usefulness that customers like, the problem will get solved. However, before trying to solve the problem, verify customers will buy what you’re selling.

No-To-Yes. Small increases in efficiency and productivity don’t cause customers to radically change their buying habits. For that your new product or service must do something new. In a No-To-Yes way, the old one couldn’t but the new one can. If solving the problem turns no to yes, it will get solved.

Would they buy it? Before solving, make sure customers will buy the useful novelty. (To know, clearly define the novelty in a hand sketch and ask them what they think.) If they say yes, see the next question.

Would it meet our growth objectives? Before solving, do the math. Does the solution result in incremental sales larger than the growth objective? If yes, see the next question.

Would we commercialize it? Before solving, map out the commercialization work. If there are no resources to commercialize, stop. If the resources to commercialize would be freed up, solve it.

Defining is solving. Up until now, solving has been premature. And it’s still not time. Create a functional model of the existing product or service using blocks (nouns) and arrows (verbs). Then, to create the problem(s), add/modify/delete functions to enable the novel usefulness customers will buy. There will be at least one problem – the system cannot perform the new function. Now it’s time to take a deep dive into the physics and bring the new function to life. There will likely be other problems. Existing functions may be blocked by the changes needed for the new function. Harmful actions may develop or some functions will be satisfied in an insufficient way. The key is to understand the physics in the most complete way. And solve one problem at a time.

Adaptation before creation. Most problems have been solved in another industry. Instead of reinventing the wheel, use TRIZ to find the solutions in other industries and adapt them to your product or service. This is a powerful lever to reduce innovation risk.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem. And you know it’s the wrong problem if the solution doesn’t: solve a business problem, achieve the growth objective, create more sales, provide No-To-Yes functionality customers will buy, and you won’t allocate the resources to commercialize.

And if the problem successfully runs the gauntlet and is worth solving, spend time to define it rigorously. To understand the bedrock physics, create a functional of the system, add the new functionality and see what breaks. Then use TRIZ to create a generic solution, search for the solution across other industries and adapt it.

The key to innovation is problem solving. But to reduce the risk, before solving, spend time and energy to make sure it’s the right problem to solve.

It’s far faster to solve the right problem slowly than to solve the wrong one quickly.

Image credit – Kate Ter Haar

Before you can make a million, you’ve got to make the first one.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

With process improvement, the existing process is refined over time. With innovation, the work is new. You can’t improve a process that does not yet exist. Process creation, yes. Process improvement, no.

Standard work, where the sequence of process steps has proven successful, is a pillar of the manufacturing mindset. In manufacturing, if you’re not following standard work, you’re not doing it right. But with innovation, when the work is done for the first time, there can be no standard work. In that way, if you’re following the standard work paradigm, you are not doing innovation.

In a well-established manufacturing process, problems are tightly scoped and constrained. There can be several ways to solve it and one of the ways is usually better than the others. Teams are asked to solve the problem three or four ways and explain the rationale for choosing one solution over the other. With innovation it’s different. There may not be a solution, never mind three. With innovation, it’s one-in-a-row solution. And the real problem is to decide which problem to solve. If you’re asked to use Fishbone diagrams to solve the problem three or four ways, you’re not doing innovation. Solve it one way, show a potential customer and decide what to do next.

With manufacturing and product development, it’s all about Gantt charts and hitting dates. The tasks have a natural precedence and all of them have been done before. There are branches in the plan, but behind them is clear if-then logic. With innovation, the first task is well-defined. And the second task – it depends on the outcome of the first. And completion dates? No way. If you can predict the completion date, you’re not doing innovation. And if you’re asked for a fully built-out Gantt chart, you’re in trouble because that’s a misguided request.

Systems in manufacturing can be complicated, with lots of moving parts. And the problems can be complicated. But given enough time, the experts can methodically figure it out. But with innovation, the systems can be complex, meaning they are not predictable. Sometimes parts of the system interact strongly with other parts and sometimes they don’t interact at all. And it’s not that they do one or the other, it’s that they do both. It’s like they have a will of their own, and, sometimes, they have a bad attitude. And if it’s a new system, even the basic rules of engagement are unknown, never mind the changing strength of the interactions. And if the system is incomplete and you don’t know it, linear thinking of the experts can’t solve it. If you’re using linear problem solving techniques, you’re not doing innovation.

Manufacturing is about making one thing a million times. Innovation is about choosing among the million possibilities and making one-in-a-row, and then, after the bugs are worked out, making the new thing a million times. But one-in-a-row must come first. If you can’t do it once, you can’t do it a million times, even with process improvement, standard work, Gantt charts and Fishbone diagrams.

Image credit jacinta lluch valero

Success – the Enemy of New Work

Success is the enemy of new work. Past success blocks new work out of fear it will jeopardize future success, and future success blocks new work out of fear future success will actually come to be.

Success is the enemy of new work. Past success blocks new work out of fear it will jeopardize future success, and future success blocks new work out of fear future success will actually come to be.

Either way you look at it, success gets in the way of doing new work.

Success itself has no power to block new work. To generate its power, past success creates the fear of loss in the people doing today’s work. And their fear causes them to block new work. When we did A we got success, and now you are trying to do B. B is not A, and may not bring success. I will resist B out of fear of losing the goodness of past success.

As a blocking agent, future success is more ethereal and more powerful because it prevents new work from starting. Future success causes our minds to project the goodness and glory the new work could bring and because our small sense of self doesn’t think we’re worthy, we never start. Where past success creates an enemy in the status quo, future success creates an enemy within ourselves.

But if we replace fear with learning, the game changes.

I’m not trying to displace our past success, I’m trying to learn if we can use it as springboard and back flip into the deep end of our future success. If it works, our learning will refine today’s success and inform tomorrow’s. If it doesn’t work, we’ll learn what doesn’t work and try something else. But not to worry, we’ll make small bets and create big learning. That way when we jump in the puddle, the splash will be small. And if the water’s cold, we’ll stop. But if it’s warm, we’ll jump into a bigger puddle. And maybe we’ll jump together. What do you think? Will you help me learn?

Yes, it’s scary to think about running this small experiment. Not because it won’t work, but because it might. If we learn this could work it would be a game-changer for the company and I’m afraid I’m not worthy of the work. Can you help me navigate this emotional roller coaster? Can you help me learn if this will work? Can you review the results privately and help me learn what’s going on? If we don’t learn how to do it, our competitors will. Can you help me start?

Success blocks, but it also pays the bills. And, hopefully it’s always part of the equation. But there are things we can do to take the edge of its blocking power. Acknowledge that new work is scary and focus on learning. Learning isn’t threatening, and it moves things forward. Show results and ask for comments from people who created past success. Over time, they’ll become important advocates. And acknowledge to yourself that new work creates internal fear, and acknowledge the best way to push through fear is to learn.

Be afraid, make small bets and learn big.

Image credit – Andy Morffew

Innovation and the Mythical Idealized Future State

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

When it’s time to innovate, the first task is usually to define the Idealized Future State (IFS). The IFS is a word picture that captures what it looks like when the innovation work has succeeded beyond our wildest dreams. The IFS, so it goes, is directional so we can march toward the right mountain and inspirational so we can sustain our pace over the roughest territory.

For the IFS to be directional, it must be aimed at something – a destination. But there’s a problem. In a sea of uncertainty, where the work has never been done before and where there are no existing products, services or customers, there are an infinite number of IFRs/destinations to guide our innovation work. Open question – When the territory is unknown, how do we choose the right IFS?

For the IFS to be inspirational, it must create yearning for something better (the destination). And for the yearning to be real, we must believe the destination is right for us. Open question – How can we yearn for an IFS when we really can’t know it’s the right destination?

Maps aren’t the territory, but they are a collection of all possible destinations within the design space of the map. If you have the right map, it contains your destination. And for a long time now, the old paper maps have helped people find their destinations. But on their own maps don’t tell us the direction to drive. If you have a map of the US and you want to drive to Kansas, in which direction do you drive? It depends. If in California, drive east; if in Mississippi, drive north; if in New Hampshire, drive west; and in Minnesota, drive south. If Kansas is your idealized future state, the map alone won’t get your there. The direction you drive depends on your location.

GPS has been a nice addition to maps. Enter the destination on the map, ask the satellites to position us globally and it’s clear which way to drive. (I drive west to reach Kansas.) But the magic of GPS isn’t in the electronic map, GPS is magic because it solves the location problem.

Before defining the idealized future state, define your location. It grounds the innovation work in the reality of what is, and people can rally around what is. And before setting the innovation direction with the IFS, define the next problems to solve and walk in their direction.

Image credit – Adrian Brady

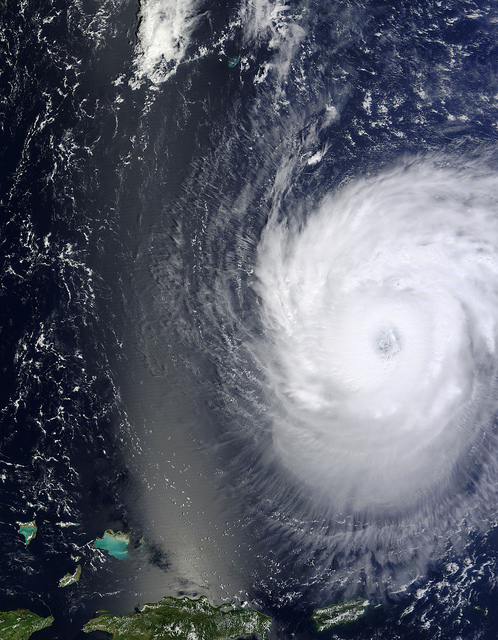

Forecasting The Next Big Technology

When a hurricane is on the horizon, we are all glued to our TVs. We want to know where it track so we know we’ll be safe. Will it track north and rumble over the top of us or will it track east and head out to sea? This is not trivial. In one scenario we lose our house and in the other the crazy surfers get to ride huge waves.

When a hurricane is on the horizon, we are all glued to our TVs. We want to know where it track so we know we’ll be safe. Will it track north and rumble over the top of us or will it track east and head out to sea? This is not trivial. In one scenario we lose our house and in the other the crazy surfers get to ride huge waves.

The meteorologist shows us a time-lapse of the storm center hour-by-hour. It was one hundred miles off shore an hour ago, it’s fifty miles off shore now and it will hit the shoreline in an hour. Drawing a line from where it was, through its location in the moment, the meteorologist can extrapolate where it will be an hour from now. In the short term, the storms trajectory will be unchanged and its momentum will help it maintain its pace. It’s pretty clear to everyone where the storm will be in an hour. No magic here.

But the good meteorologists can forecast a hurricane’s path days in advance. In a phenomenological way, they use behavior models of past storms, assume this storm is like past storms, turn the crank and forecast its trajectory. And they’re right more times than not. And they’re right enough to determine who should evacuate and who should sit tight. This is borderline magic.

The best meteorologists know where hurricanes want go because they understand hurricanes. They know hurricanes want to run in straight lines, if not follow gentle curves. They know hurricanes get anxious when they hop from sea to land, and they know, given the choice, will skirt the coastline and head back home to the salt water. Meteorologists know the rules hurricane’s live by and use that knowledge to tighten their forecast of the storm’s path.

Just as hurricanes have a desire to follow their hearts, technologies have a similar desire climb the evolutionary ladder. Just as hurricanes behave like their predecessors, technologies behave like their grandparents, aunts and uncles. And just as a meteorologist, using their knowledge of historical patterns and an understanding of hurricane genetics can forecast the path of a hurricane, technologists can forecast the path of technologies using historical patterns and an understanding of what technologies want.

And like with hurricanes, the best way to forecast the path of a technology is to define where it was, draw a line through where it is and project its trajectory into the future. Like hurricanes, technologies move in straight lines or gentle S-curves, so their next move is easy to forecast. If a technology has improved year-over-year, it will likely continue to improve. And if this year’s performance is the same as last year, it’s behavior will remain unchanged going forward. That’s how it goes with technologies.

The best technologists are like horse whisperers in that they can hear the inner voice of technologies. They know when a technology is ready to grow from infant to adolescent and know when a technology is ready to retire. The best technologists can read the tea leaves of the patent landscape and, knowing the predisposition of technologies, can forecast the next evolution. But just as some ranch owners don’t believe in horse whisperers, some company leaders don’t believe technology whisperers can forecast technologies.

But for believers and non-believers alike, it’s more effective to compare forecasting capabilities of technologists with the forecasting capabilities of meteorologists. The notions of trajectory and momentum have clear physical interpretations for hurricanes and technologies, and historical models of storm trajectories map directly to evolutionary paths of technologies.

If you’re looking to forecast where the next big storm will make landfall, hire a great meteorologist. But if you’re looking to forecast when the next technology will rip the roof off your business model, hire a great technology whisperer.

Image credit – NASA

If you don’t know what to do, you may be on the right track.

You had to push through your fear of being judged?

You had to break some rules to get an idea off the ground?

You had a concept that would displace your most successful product?

Your colleague tried to scuttle your best idea?

You knew it was time to stop judging yourself negatively?

Your colleague asked you to help with a hair-brained idea?

You were asked to facilitate a session to create new concepts, but no one could explain what would happen after the concepts were created?

You weren’t afraid your prototype would be a success?

You thought you knew what the customer wanted, but didn’t have the data to prove it?

You were asked to create patentable concepts you knew would never be commercialized?

Your prototype threatened the status quo?

You were asked to facilitate a session to create new concepts and told how to do it?

You were told “No.”

You saw a young employee struggling with a new concept?

You were blocking yourself from starting the right work?

You thought your idea had merit, but you needed help testing it in the market?

You were asked to follow a standard process but you knew there wasn’t one?

You were asked to come up with new concepts though there were five excellent concepts gathering dust?

You were told there was no market for your new-to-world prototype?

You had to bolster your self-confidence to believe wholeheartedly in your idea?

There is a name for what you would do. It’s called innovation.

image credit – UnknownNet Photography

Dismantle the business model.

When companies want to innovate, there are three things they can change – products, services and business models. Products are usually the first, second and third priorities, services, though they have a tighter connection with customer and are more lasting and powerful, sadly, are fourth priority. And business models are the superset and the most powerful of all, yet, as a source of innovation, are largely off limits.

When companies want to innovate, there are three things they can change – products, services and business models. Products are usually the first, second and third priorities, services, though they have a tighter connection with customer and are more lasting and powerful, sadly, are fourth priority. And business models are the superset and the most powerful of all, yet, as a source of innovation, are largely off limits.

It’s easy to improve products. Measure goodness using a standard test protocol, figure out what drives performance and improve it. Create the hard data, quantify the incremental performance and sell the difference. A straightforward method to sell more – if you liked the last one, you’re going to like this one. But this is fleeting. Just as you are reverse engineering the competitors’ products, they’re doing it to you. Any incremental difference will be swallowed up by their next product. The half-life of your advantage is measured in months.

It’s easy for companies to run innovation projects to improve product performance because it’s easy to quantify the improvement and because we think customers are transactional. Truth is, customers are emotional, not rational. People don’t buy performance, they buy the story they create for themselves.

Innovating on services is more difficult because, unlike a product, it’s not a physical thing. You can’t touch it, smell it or taste it. Some say you can measure a service, but you can’t. You can measure its footprints in the sand, but you can’t measure it directly. All the click data in the world won’t get you there because clicks, as measured, don’t capture intent – an unintentional click on the wrong image counts the same a premeditated click on the right one. Sure, you can count clicks, but if you can’t count the why’s, you don’t have causation. And, sure, you can measure customer satisfaction with an online survey, but the closest you can get is correlation and that’s not good enough. It’s causation or bust. You’ve got to figure out WHY they like your services. (Hint – it’s the people who interface directly with your customers and the latitude you give them to advocate on the customers’ behalf.)

Where services are difficult to innovate, the business model is almost impossible. No one is quite sure what the business model actually is an in-the-trenches-way, but they know it’s been responsible for the success of the company, and they don’t want to change it. Ultimately, if you want to innovate on the business model, you’ve got to know what it is, but before you spend the time and energy to define it, it’s best to figure out if it needs changing. The question – what does it look like when the business model is out of gas?

If you do what you did last time and you get less in return, the business model is out of gas.

Successful models are limiting. Just like with the Prime Directive, where Captain Kirk could do anything he wanted as long as he didn’t interfere with the internal development of alien civilizations, do anything you want with the business model as long as you don’t change it. And that’s why you need external help to formally define the business model and experiment with it. The resource should understand your business first hand, yet be outside the chain of command so they can say the sacrilegious things that violate the Prime Directive without being fired. For good candidates, look to trusted customers and suppliers.

To define the business model, use a simple block diagram (one page) where blocks are labelled with simple nouns and arrows are labelled with simple verbs. Start with a single block on the right of the page labelled “Customer” and draw a single arrow pointing to the block and label it. Continue until you’ve defined the business model. (Note – maximum number of blocks is 12.) You’ll be surprised with the difficulty of the process.

After there’s consensus on the business model, the next step is to figure out how the environment changed around it and to identify and test the preferred evolutionary paths. But that’s for another time.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Full Circle Innovation

It’s not enough to sell things to customers, because selling things is transactional and, over time, transactional selling deteriorates into selling on price. And selling on price is a race to the bottom.

It’s not enough to sell things to customers, because selling things is transactional and, over time, transactional selling deteriorates into selling on price. And selling on price is a race to the bottom.

Sales must move from transactional to relational, where people in the sales organization become trusted advisers and then something altogether deeper. At this deeper level of development, the sales people know the business as well as the customer, know where the customer wants to go and provide unique perspective and thoughtful insight. That’s quite a thing for sales, but it’s not enough. Sales must become the conduit that brings the entire company closer to the customer and their their work.

When the customer is trying to figure out what’s next, sales brings in a team of marketing, R&D and manufacturing to triangulate on the future. The objective is to develop deep understanding of the customer’s world. The understanding must go deeper than the what’s. The learning must scrape bottom and get right down to the bedrock why’s.

To get to bedrock, marketing leads learning sessions with the customer. And it all starts by understanding the work. What does the customer do? Why is it done that way? What are the most important processes? How did they evolve? Why do they flow the way they do? These aren’t high-level questions, they are low-level, specific questions, done in front of the actual work.

The mantra – Go to the work.

When the learning sessions are done well, marketing includes experts in manufacturing and R&D. Manufacturing brings their expertise in understanding process and R&D brings their expertise in products and technologies. And to understand the work the deepest way, the tool of choice is the Value Stream Map (VSM).

Cross-organization teams are formed (customer, sales, marketing, manufacturing, and R&D) and are sent out to create Value Steam Maps of the most important processes. (Each team is supported by a VSM expert.) Once the maps are made, all the teams come back together to review the them and identify the fundamental constraints and how to overcome them. The solutions are not limited to new product offerings, rather the solutions could be training, process changes, policy changes, organizational changes or business model changes.

Not all the problems are solved in the moment. After the low hanging fruit is picked, the real work begins. After returning home, marketing and R&D work together to formulate emergent needs and create new ways to meet them. The tool of choice is the IBE (Innovation Burst Event).

To prepare for the IBE, marketing and R&D formalize emergent needs and create Design Challenges to focus the IBE teams. Solving the Design Challenges breaks the conflicts creates novel solutions that meet the unmet needs. In this way, the IBE is a pull process – customer needs create the pull for a solution.

The IBE is a one or two-day event where teams solve the Design Challenges by building conceptual prototypes (thinking prototypes). Then, they vote on the most interesting concepts and create a build plan (who, what, when). The objective of the build plan is to create a Diabolically Simple Prototype (DSP), a functional prototype that demonstrates the new functionality. What makes it diabolical is quick build time. At the end of the IBE is a report out of the build plan to the leader who can allocate the resources to execute it.

In a closed-loop way, once the DSP is built, sales arranges another visit to the customer to demonstrate the new solution. And because the prototype designed to fulfill the validated customer need, by definition, the prototype will be valuable to the customer.

This full circle process has several novel elements, but the magic is in the framework that brings everyone together. With the process, two companies can work together effectively to achieve shared business objectives. And, because the process brings together multiple functions and their unique perspectives, the solutions are well-thought-out and grounded in the diversity of the collective.

Image credit – Gerry Machen

With innovation you’ve got to feel worthy of the work.

When doing work that’s new, sometimes it seems the whole world is working against you. And, most of the time, it is. The outside world is impossible to control, so the only way to deal with external resistance is to pretend you don’t hear it. Shut your ears, put your head down and pull with all your might. Define your dream and live it. And don’t look back. But what about internal resistance?

When doing work that’s new, sometimes it seems the whole world is working against you. And, most of the time, it is. The outside world is impossible to control, so the only way to deal with external resistance is to pretend you don’t hear it. Shut your ears, put your head down and pull with all your might. Define your dream and live it. And don’t look back. But what about internal resistance?

Where external resistance cannot be controlled and must be ignored, internal resistance, resistance created by you, can be actively managed. The best way to deal with internal resistance is to prevent its manufacture, but very few can do that. The second best way is to acknowledge resistance is self-made and acknowledge it will always be part of the innovation equation. Then, understand the traps that cause us to create self-inflicted resistance and learn how to work through them.

The first trap prevents starting. At the initial stage of a project, two unstated questions power the resistance – What if it doesn’t work? and What if it does work? If it doesn’t work, the fear is you’ll be judged as incompetent or crazy. The only thing to battle this fear is self-worth. If you feel worthy of the work, you’ll push through the resistance and start. If it does work, the fear is you won’t know how to navigate success. Again, if you think you’re worthy of the work (the work that comes with success), you and your self-esteem will power through the resistance and start.

Underpinning both questions is a fundamental of new work that is misunderstood – new work is different than standard work. Where standard work follows a well-worn walking path, new work slashes through an uncharted jungle where there are no maps and no GPS. With standard work, all the questions have been answered, the scope is well established and the sequence of events and timeline are dialed in. With standard work, everything is known up front. With new work, it’s the opposite. Never mind the answers, the questions are unknown. The scope is uncertain and the sequence of events is yet to be defined. And the timeline cannot be estimated.

But with so much standard work and so little new work, companies expect people to that do the highly creative work to have all the answers up front. And to break through the self-generated resistance, people doing new work must let go of self-imposed expectations that they must have all the answers before starting. With innovation, the only thing that can be known is how to figure out what’s next. Here’s a generic project plan for new work – do the first thing and then, based on the results, figure out what to do next, and repeat.

To break through the trap that prevents starting, don’t hold yourself accountable to know everything at the start. Instead, be accountable for figuring out what’s next.

The second trap prevents progress. And, like the first trap, resistance-based paralysis sets in because we expect ourselves to have an etched-in-stone project plan and expect we’ll have all the answers up front. And again, there’s no way to have the right answers when the first bit of work must be done to determine the right questions. If you think you’re worthy of the work, you’ll be able to push through the resistance with the figure out what’s next approach.

When in the middle of an innovation project, hold yourself accountable to figuring out what to do next. Nothing more, nothing less. When the standard work police demand a sequence of events and a timeline, don’t buckle. Tell them you will finish the current task then define the next one and you won’t stop until you’re done. And if they persist, tell them to create their own project plan and do the innovation work themselves.

With innovation, it depends. With innovation, hold onto your self-worth. With innovation, figure out what’s next.

Image credit — Jonathan Kos-Read

Diabolically Simple Prototypes

Ideas are all talk and no action. Ideas are untested concepts that have yet to rise to the level of practicality. You can’t sell an idea and you can’t barter with them. Ideas aren’t worth much.

Ideas are all talk and no action. Ideas are untested concepts that have yet to rise to the level of practicality. You can’t sell an idea and you can’t barter with them. Ideas aren’t worth much.

A prototype is a physical manifestation of an idea. Where ideas are ethereal, prototypes are practical. Where ideas are fuzzy and subject to interpretation, prototypes are a sledge hammer right between the eyes. There is no arguing with a prototype. It does what it does and that’s the end of that. You don’t have to like what a prototype stands for, but you can’t dismiss it. Where ideas aren’t worth a damn, prototypes are wholly worth every ounce of effort to create them.

If Camp A says it will work and Camp B says it won’t, a prototype will settle the disagreement pretty quickly. It will work or it won’t. And if it works, the idea behind it is valid. And if it doesn’t, the idea may be valid, but a workable solution is yet-to-be discovered. Either way, a prototype brings clarity.

Prototypes are not elegant. Prototypes are ugly. The best ones do one thing – demonstrate the novel idea that underpins them. The good ones are simple, and the best ones are diabolically simple. It is difficult to make diabolically simple prototypes (DSPs), but it’s a skill that can be learned. And it’s worth learning because DSPs come to life in record time. The approach with DSPs is to take the time up front to distill the concept down to its essence and then its all-hands-on-deck until it’s up and running in the lab.

But the real power of the DSP is that it drives rapid learning. When a new idea comes, it’s only a partially formed. The process of trying to make a DSP demands the holes are filled and blurry parts are brought into focus. The DSP process demands a half-baked idea matures into fully-baked physical embodiment. And it’s full-body learning. Your hands learn, your eyes learn and your torso learns.

If you find yourself in a disagreement of ideas, stop talking and start making a prototype. If the DSP works, the disagreement is over.

Diabolically simple prototypes end arguments. But, more importantly, they radically increase the pace of learning.

Image credit – snippets101

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski