Archive for the ‘Innovation’ Category

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

The primary impediment to innovation is fear, and the prime directive of any innovation system should be to drive out fear.

A culture of accountability, implemented poorly, can inject fear and deter innovation. When the team is accountable to deliver on a project but are constrained to a fixed scope, a fixed launch date and resources, they will be afraid. Because they know that innovation requires new work and new work is inherently unpredictable, they rightly recognize the triple accountability – time, scope and resources – cannot be met. From the very first day of the project, they know they cannot be successful and are afraid of the consequences.

A culture of accountability can be adapted to innovation to reduce fear. Here’s one way. Keep the team small and keep them dedicated to a single innovation project. No resource sharing, no swapping and no double counting. Create tight time blocks with clear work objectives, where the team reports back on a fixed pitch (weekly, monthly). But make it clear that they can flex on scope and level of completeness. They should try to do all the work within the time constraints but they must know that it’s expected the scope will narrow or shift and the level of completeness will be governed by the time constraint. Tell them you believe in them and you trust them to do their best, then praise their good judgement at the review meeting at the end of the time block.

Innovation is about solving new problems, yet fear blocks teams from trying new things. Teams like to solve problems that are familiar because they have seen previous teams judged negatively for missing deadlines. Here’s the logic – we’d rather add too little novelty than be late. The team would love to solve new problems but their afraid, based on past projects, that they’ll be chastised for missing a completion date that’s disrespectful of the work content and level of novelty. If you want the team to solve new problems, give them the tools, time, training and a teacher so they can select different problems and solve them differently. Simply put – create the causes and conditions for fear to quietly slink away so innovation will flow.

Fear is the most powerful inhibitor. But before we can lessen the team’s fear we’ve got to recognize the causes and conditions that create it. Fear’s job is to keep us safe, to keep us away from situations that have been risky or dangerous. To do this, our bodies create deep memories of those dangerous or scary situations and creates fear when it recognizes similarities between the current situation and past dangerous situations. In that way, less fear is created if the current situation feels differently from situations of the past where people were judged negatively.

To understand the causes and conditions that create fear, look back at previous projects. Make a list of the projects where project members were judged negatively for things outside their control such as: arbitrary launch dates not bound by the work content, high risk levels driven by unjustifiable specifications, insufficient resources, inadequate tools, poor training and no teacher. And make a list of projects where team members were praised. For the projects that praised, write down attributes of those projects (e.g., high reuse, low technical risk) and their outcomes (e.g., on time, on cost). To reduce fear, the project team will bend new projects toward those attributes and outcomes. Do the same for projects that judged negatively for things outside the project teams’ control. To reduce fear, the future project teams will bend away from those attributes and outcomes.

Now the difficult parts. As a leader, it’s time to look inside. Make a list of your behaviors that set (or contributed to) causes and conditions that made it easy for the project team to be judged negatively for the wrong reasons. And then make a list of your new behaviors that will create future causes and conditions where people aren’t afraid to solve new problems in new ways.

Image credit — andrea floris

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

Image credit – NASA

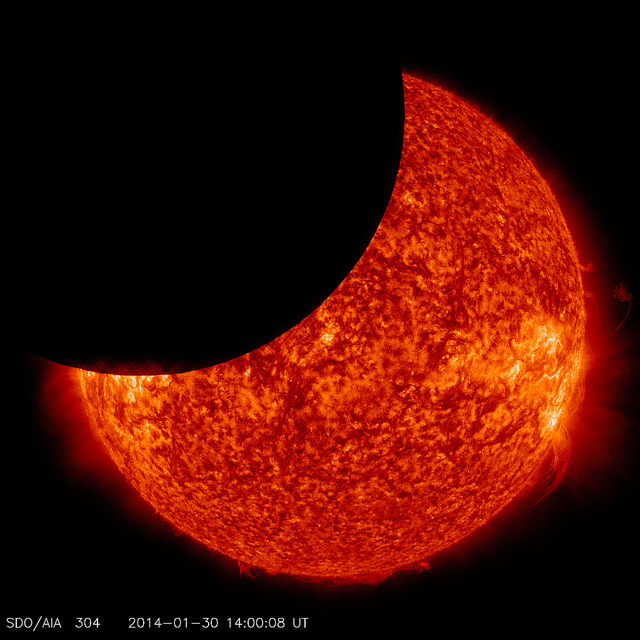

The right time horizon for technology development

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

It’s easy to measure the number of patents and easier to measure profits. But there’s a problem. Not all patents (technologies) are equal and not all profits are equal. You can have a stockpile of low-level patents that make small improvements to existing products/services and you can have a stockpile of profits generated by short-term business practices, both of which are far less valuable than they appear. If you measure the number of patents without evaluating the level of inventiveness, you’re running your business without a true understanding of how things really are. And if you’re looking at the pile of profits without evaluating the long-term viability of the engine that created them you’re likely living beyond your means.

In both cases, it’s important to be aware of your time horizon. You can create incremental technologies that create short term wins and consume all your resource so you can’t work on the longer-term technologies that reinvent your industry. And you can implement business practices that eliminate costs and squeeze customers for next-quarter sales at the expense of building trust-based engines of growth. It’s all about opportunity cost.

It’s easy to develop technologies and implement business processes for the short term. And it’s equally easy to invest in the long term at the expense of today’s bottom line and payroll. The trick is to balance short against long.

And for patents, to achieve the right balance rate your patents on the level of inventiveness.

Image credit – NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory

Situational Awareness (Winter is Coming)

Business and life are all about choosing how you want to allocate your time and money. In life, it’s your personal time and money and in business it’s the company’s.

Business and life are all about choosing how you want to allocate your time and money. In life, it’s your personal time and money and in business it’s the company’s.

If you’ve ever done any winter hiking, you know that it’s important to know the terrain. If there’s a mountain in the way, you either go over it or around it. But there is one thing you can’t do is pretend it’s not there. If you go around it, you’ve got to make sure you have enough energy, food, water and daylight to make the long trek to shelter. If you go over it, you’ve got to make sure you have the ice picks, crampons, down jackets and climbing skills to make it up and down to shelter. With winter hiking, the territory, gear and team capability matter. And the right decision is defined by situational awareness.

And what of the shelter? Does it sleep five, six or seven? And because you have seven on your team, it’s not really shelter if it sleeps five. And if you don’t know how many it sleeps, you’re not situationally aware. And if you’re not situationally aware, on five may fit in the shelter and two will freeze to death. Maybe before your trip you should look at the map and learn all the shelters their locations and how many the can hold. The right action and the safety of your crew depends on your situational awareness.

And the decision depends on how much daylight do you have left. Before you left basecamp it was possible to know when the sun will set. Did you take the time to look at the charts? Did you take advantage of the knowledge? If you don’t have enough sunlight, you’ve got to go over the top. If you do, you can take the leisurely great circle route around the mountain. And if you don’t know, you’ve got to roll the dice. I’d prefer to be aware of the situation and keep the dice in my pocket. And for that, you need to be aware of the situation.

Winter hiking is difficult enough even when you have maps of the terrain, weather forecasts, locations of the shelters and knowledge of when the sun will set. But it’s an unsafe activity when there are no maps of the territory, the weather is unknown and there’s no knowledge of the shelters. But that’s just how it is with innovation – the territory has never been hiked, no maps, no weather forecast, and shelters are unknown. With innovation, there’s no situational awareness unless you create it. And that’s why with innovation, the first step is to create the maps. No maps, no possibility of situational awareness.

The best people at situational awareness are the military. The know maps and they know how to use them. The know to do recon to position the enemy on the map and they know to use the situational awareness (the map, the enemy’s location, and their direction of travel) to decide how what to do. If the enemy’s force is small and in poorly defensible position, there are a certain set of actions that are viable. If the enemy force is large and has the high ground, it’s time to sit tight or retreat with dignity. (To be clear, I’m a pacifist and this military example does mean I condone violence of any kind. It’s just that the military is super good at situational awareness.)

If you’re not making maps of the competitive landscape, you’re doing it wrong. If you’re not moving resources around and speculating how the competition will respond based on the topography and your position within it, you’re not sharpening your situational awareness and you’re not taking full advantage of the information around you. If you don’t know where the mountains are you can’t avoid them or use them to slow your competition. And if you don’t know know where the shelters are an how many miles you can hike in a day, you don’t know if you’re overextending your position and putting your crew at risk.

Winter is coming. If you’re not creating maps to build situational awareness, what are you doing?

Image credit – Martin Fisch

Testing the Business Model

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

Sometimes we get caught up in the details when we should be working on the foundation. Here’s a rule: If the underlying foundation is not secure, don’t bother working on anything else.

If you’re working on a couple new technologies, but the overall business model won’t be profitable, don’t work on the new technologies. Instead, figure out a business model that is profitable, then do what it takes (technology, simplification, process improvement) to make it happen. But, often, that’s not what we do.

Often, we put the cart before the horse. We create projects to make prototypes that demonstrate a new technology, but the whole business premise is built on quicksand. There’s a reason why foundations are made from concrete and not quicksand. It’s because you can build on top of a base made of concrete. It supports the load. It doesn’t crack, nor does it fall apart. Think Pyramid of Giza.

Because foundations are big and expensive they can be difficult and expensive to test. For example, if an innovation is based on a new foundation, say, a new business model, building a physical prototype of the new business model is too expensive and the testing will not happen. And what usually happens is the foundation goes untested, the higher level technology work is done, the commercialization work is completed and the business model fails because it wasn’t solid.

But you don’t have to build a full-scale prototype of the Pyramid of Giza to test if a pyramid will stand the test of time. You can build a small one and test it, or you can run an analysis of some sort to understand if the pyramid will support the weight. But what if you want to test a new business model, a business model that has never been done before, using new products and services that have never seen the light of day? What do you do? In this case, it doesn’t make sense to make even a scale model. But it does make sense to create a one page sales tool that describes the whole thing and it does make sense to show it to potential customers and ask them what they think about it.

The open question with all new things is – will customers like it enough to buy it. And, it’s no different with the business model. Instead of creating a new website, staffing up, creating new technologies and products, create a one-page sales tool that describes the new elements and show it to potential customers. Distill the value proposition into language people can understand, describe the novelty that fuels the value, capture it on one page, show it to customers, and listen.

And don’t build a single, one-page sales tool, build two or three versions. And then, ask customers what they think. Odds are, they’ll ask you questions you didn’t think they’d ask. Odds are, they’ll see it differently than you do. And, odds are, you’ll have to incorporate their feedback into an improved version of the business model. The bad new is you didn’t get it right. The good news is you didn’t have to staff up and build the whole business model, create the technologies and launch the products. And more good news – you can quickly modify the one-page sales tool and go back to the customers and ask them what they think. And you can do this quickly and inexpensively.

Don’t develop the technology until you know the underlying business model will be profitable. Don’t staff up until you know if the business model holds water. Don’t launch the new products until you verify customers will buy what you want to sell.

Creating a new business model from scratch is an expensive proposition. Don’t build it until you invest in validating it’s worth building.

The worst way to validate a business model is by building it.

Image credit – David Stanley

How to Choose the Best Idea

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

Before creating more ideas, make a list of the ones you already have. Put them in two boxes. In Box 1, list the ideas without a video of a functional prototype in action. In Box 2, list the ideas that have a video showing a functional prototype demonstrating the idea in action. For those ideas with a functional prototype and no video, put them in Box 1.

Next, throw away Box 1. If it’s not important enough to make a crude physical prototype and create a simple video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If someone isn’t willing to carve out the time to make a physical prototype, there’s no emotional energy behind the idea and it should be left to die. And when people complain that it’s unfair to throw away all those good ideas in Box 1, tell them it’s unfair to spend valuable resources talking about ideas that aren’t worthy. And suggest, if they want to have a discussion about an idea, they should build a physical prototype and send you the video. Box 2, or bust.

Next, get the band together and watch the short videos in Box 2, and, as a group, put them in two boxes. In Box 3, put the videos without customers actively using the functional prototype. In Box 4, put the videos with customers actively using the functional prototype.

Next, throw way Box 3. If it’s not important enough to make a trip to an important customer and create a short video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If you’re not willing to put yourself out there and take the idea to an important customer, the idea is all fizzle and no sizzle. Meaningful ideas take immense personal energy to run through the gauntlet, and without a video of a customer using the functional prototype, there’s not enough energy behind it. And when everyone argues that Box 3 ideas are worth pursuing, tell them to pursue a video showing a most important customer demonstrating the functional prototype.

Next, get the band back together to watch the Box 4 videos. Again, put the videos in two boxes. In Box 5 put the videos where the customer didn’t say what they liked and how they’d use it. In Box 6, put the videos where the customer enthusiastically said what they liked and how they’ll use it.

Next, throw away Box 5. If the customer doesn’t think enough about the prototype to tell you how they’ll use it, it’s because they don’t think much of the idea. And when the group says the customer is wrong or the customer doesn’t understand what the prototype is all about, suggest they create a video where a customer enthusiastically explains how they’d use it.

Next, get the band back in the room and watch the Box 6 videos. Put them in two boxes. In Box 7, put the videos that won’t radically grow the top line. In Box 8, put the videos that will radically grow the top line. Throw away Box 7.

For the videos in Box 8, rank them by the amount of top line growth they will create. Put all the videos back into Box 8, except the video that will create the most top line growth. Do NOT throw away Box 8.

The video in your hand IS your company’s best idea. Immediately charter a project to commercialize the idea. Staff it fully. Add resources until adding resources doesn’t no longer pulls in the launch. Only after the project is fully staffed do you put your hand back into Box 8 to select the next best idea.

Continually evaluate Boxes 1 through 8. Continually throw out the boxes without the right videos. Continually choose the best idea from Box 8. And continually staff the projects fully, or don’t start them.

Image credit – joiseyshowaa

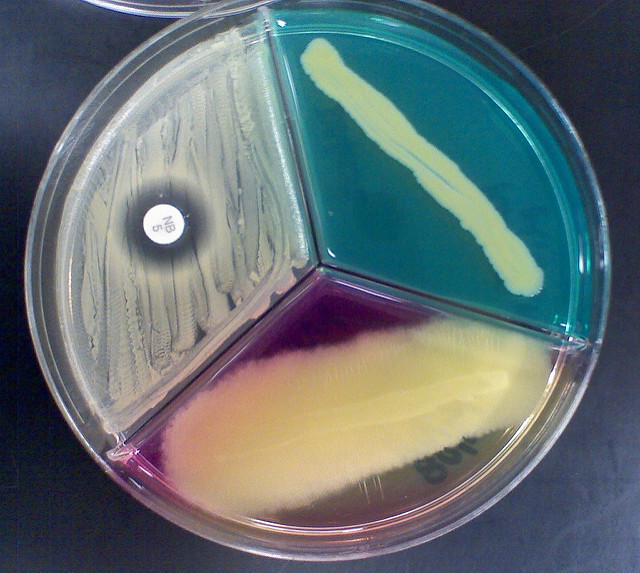

How to Avoid a Cliff

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

Much like living organisms continually evolve to secure their place in the future, technological systems can be thought to display similar evolutionary behavior. Viruses mutate so some of them can defeat the countermeasures of their host and live to fight another day. Technological systems, as an expression of a company’s desire to survive, evolve to defeat the competition and live to pay another dividend.

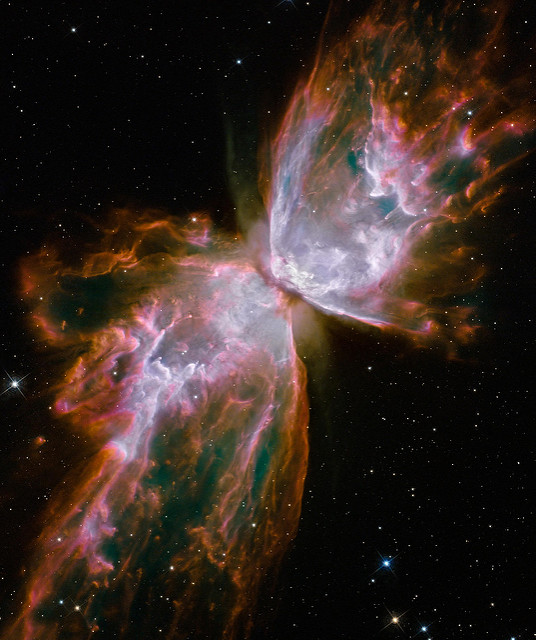

There are natural limits to evolutionary success in any single direction. When one trait is improved it pushes on the natural limits imposed by the environment. For example, a bacterium let loose in a friendly Petri dish will replicate until it eats all the food in the dish. Or, on a longer timescale, if the mass of a bird increases over generations when its food source is plentiful, the bird will get larger but will also get less agile. The predators who couldn’t catch the fast, little bird of old can easily catch and eat the sluggish heavyweight. In that way, there’s an edge condition created by the environmental Petri dishes and predators. And it’s the same with technological systems.

Companies and their technological systems evolve within their competitive environment by scanning the fitness landscape and deciding where to try to improve. The idea is to see preferential lines of improvement and create new technologies to take advantage of them. Like their smaller biological counterparts, companies are minimum energy creatures and want to maximize reward (profit) with minimum effort (expense) and will continue to leverage successful lines of evolution until it senses diminishing returns.

The diminishing returns are a warning sign that the company is approaching an edge condition (a Petri dish of a finite size). In landscape lingo, there’s a cliff on the horizon. In technology lingo, the rate of improvement of the technology is slowing. In either language, the edge is near and it’s time to evolve in a new direction because this current one is out of gas.

Like the bird whose mass increases over the generations when food is readily available, companies also get fat and slow when they successfully evolve in a single direction for too long. And like the bird, they get eaten by a more agile competitor/predator. And just as the replication rate of the bacterium accelerates as the food in the Petri dish approaches zero, a company that doesn’t react to a slowing rate of technological improvement is sure to outlive its business model.

Biology and technology are similar in that they try new things (create variants of themselves) in order to live another day. But there’s a big difference – where biology is blind (it doesn’t know what will work and what won’t), technology is sighted (people that create use their understanding to choose the variants they think will work best). And another difference is that biological evolution can build only on viable variants where technology can use mental models as scaffolds to skip non-viable embodiments to cross a chasm.

There’s no need to fall off the cliff. As a leading indicator, monitor the rate of improvement of your technology. If its rate of improvement is still accelerating, it’s time to develop the next line of evolution. If its rate is declining, you waited too long. It’s time to double down on two new lines of evolution because you’re behind the curve. And remember, like with the population of bacteria in the Petri dish, sales will keep growing right up until the business model runs out of food or a competitor eats you.

Image credit — Amanda

With novelty, less can be more.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

When it’s time to create something new, most people try to imagine the future and then put a plan together to make it happen. There’s lots of talk about the idealize future state, cries for a clean slate design or an edict for a greenfield solution. Truth is, that’s a recipe for disaster. Truth is, there is no such thing as a clean slate or green field. And because there are an infinite number of future states, it’s highly improbable your idealized future state is the one the universe will choose to make real.

To create something new, don’t look to the future. Instead, sit in the present and understand the system as it is. Define the major elements and what they do. Define connections among the elements. Create a functional diagram using blocks for the major elements, using a noun to name each block, and use arrows to define the interactions between the elements, using a verb to label each arrow. This sounds like a complete waste of time because it’s assumed that everyone knows how the current state system behaves. The system has been the backbone of our success, of course everyone knows the inputs, the outputs, who does what and why they do it.

I have created countless functional models of as-is systems and never has everyone agreed on how it works. More strongly, most of the time the group of experts can’t even create a complete model of the as-is system without doing some digging. And even after three iterations of the model, some think it’s complete, some think it’s incomplete and others think it’s wrong. And, sometimes, the team must run experiments to determine how things work. How can you imagine an idealized future state when you don’t understand the system as it is? The short answer – you can’t.

And once there’s a common understanding of the system as it is, if there’s a call for a clean sheet design, run away. A call for a clean sheet design is sure fire sign that company leadership doesn’t know what they’re doing. When creating something new it’s best to inject the minimum level of novelty and reuse the rest (of the system as it is). If you can get away with 1% novelty and 99% reuse, do it. Novelty, by definition, hasn’t been done before. And things that have never been done before don’t happen quickly, if they happen at all. There’s no extra credit for maximizing novelty. Think of novelty like ghost pepper sauce – a little goes a long way. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a clean sheet design and do the opposite.

Greenfield designs should be avoided like the plague. The existing system has coevolved with its end users so that the system satisfies the right needs, the users know how to use the system and they know what to expect from it. In a hand-in-glove way, the as-is system is comfortable for end users because it fits them. And that’s a big deal. Any deviation from baseline design (novelty) will create discomfort and stress for end users, even if that novelty is responsible for the enhancement you’re trying to deliver. Novelty violates customer expectations and violating customer expectations is a dangerous game. Again, when you think novelty, think ghost peppers. If you want to know how to handle novelty, imagine a green field and do the opposite.

This approach is not incrementalism. Where you need novelty, inject it. And where you don’t need it, reuse. Design the system to maximize new value but do it with minimum novelty. Or, better still, offer less with far less. Think 90% of the value with 10% of the cost.

Image credit – Laurie Rantala

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

Mapping the Future with Wardley Maps

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

When there’s so many new things to work on, how do you choose the next project? When you’re lost, you look at a map. And when there is no map, you make one. The first bit of work is defined by the holes in the first revision of your map. And once the holes are filled and patched, the next work emerges from the map itself. And, in a self-similar way, the next work continually emerges from the previous work until the project finishes.

But with so much new territory, how do you choose the right new territory to map? You don’t. Before there’s a need to map new territory, you must map the current territory. What you’ll learn is there are immature areas that, when made mature, will deliver new value to customers. And you’ll also learn the mature areas that must be blown up and replaced with infant solutions that will ultimately create the next evolution of your business. And as you run thought experiments on your map – projecting advancements on the various elements – the right new territory will emerge. And here’s a hint – the right new solutions will be enabled by the newly matured elements of the map.

But how do you predict where the right new solutions will emerge? I can’t tell you that. You are the experts, not me. All I can say is, make the maps and you’ll know.

And when I say maps, I mean Wardely Maps – here’s a short video (go to 4:13 for the juicy bits).

Image credit – Simon Wardley

Innovation – Words vs. Actions

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself. Companies need to meet their growth objectives and innovation is the word experts use to describe the practices and behaviors they think will maximize the likelihood of meeting those growth objectives. Innovation is a catchword phrase that has little to no meaning. Don’t ask about innovation, ask how to meet your business objectives. Don’t ask about best practices, ask how has your company been successful and how to build on that success. Don’t ask how the big companies have done it – you’re not them. And, the behaviors of the successful companies are the same behaviors of the unsuccessful companies. The business books suffer from selection bias. You can’t copy another company’s innovation approach. You’re not them. And your project is different and so is the context.

Innovation isn’t a thing in itself. Companies need to meet their growth objectives and innovation is the word experts use to describe the practices and behaviors they think will maximize the likelihood of meeting those growth objectives. Innovation is a catchword phrase that has little to no meaning. Don’t ask about innovation, ask how to meet your business objectives. Don’t ask about best practices, ask how has your company been successful and how to build on that success. Don’t ask how the big companies have done it – you’re not them. And, the behaviors of the successful companies are the same behaviors of the unsuccessful companies. The business books suffer from selection bias. You can’t copy another company’s innovation approach. You’re not them. And your project is different and so is the context.

With innovation, the biggest waste of emotional energy is quest for (and arguments around) best practices. Because innovation is done in domains of high ambiguity, there can be no best practices. Your project has no similarity with your previous projects or the tightest case studies in the literature. There may be good practice or emergent practice, but there can be no best practice. When there is no uncertainty and no ambiguity, a project can use best practices. But, that’s not innovation. If best practices are a strong tenant of your innovation program, run away.

The front end of the innovation process is all about choosing projects. If you want to be more innovative, choose to work on different projects. It’s that simple. But, make no mistake, the principle may be simple the practice is not. Though there’s no acid test for innovation, here are three rules to get you started. (And if you pass these three tests, you’re on your way.)

- If you’ve done it before, it’s not innovation.

- If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

- If it doesn’t scare the hell out of you, it’s not innovation.

Once a project is selected, the next cataclysmic waste of time is the construction of a detailed project plan. With a well-defined project, a well-defined project plan is a reasonable request. But, for an innovation project with a high degree of ambiguity, a well-defined project plan is impossible. If your innovation leader demands a detailed project plan, it’s usually because they are used running to well-defined continuous improvement projects. If for your innovation projects you’re asked for a detailed project plan, run away.

With innovation projects, you can define step 1. And step 2? It depends. If step 1 works, modify step 2 based on the learning and try step 2. And if step 1 doesn’t work, reformulate step 1 and try again. Repeat this process until the project is complete. One step at a time until you’re done.

Innovation projects are unpredictable. If your innovation projects require hard completion dates, run away.

Innovation projects are all about learning and they are best defined and managed using Learning Objectives (LOs). Instead of step 1 and step 2, think LO1 and LO2. Though there’s little written about LOs, there’s not much to them. Here’s the taxonomy of a LO: We want to learn if [enter what you want to learn]. Innovation projects are nothing more than a series of interconnected LOs. LO2 may require the completion of LO1 or L1 and LO2 could be done in parallel, but that’s your call. Your project plan can be nothing more than a precedence diagram of the Learning Objectives. There’s no need for a detailed Gantt chart. If you’re asked for a detailed Gantt chart, you guessed it – run away.

The Learning Objective defines what you learn, how you want to learn, who will do the learning and when they want to do it. The best way to track LOs is with an Excel spreadsheet with one tab for each LO. For each LO tab, there’s a table that defines the actions, who will do them, what they’ll measure and when they plan to get the actions done. Since the tasks are tightly defined, it’s possible to define reasonable dates. But, since there can be a precedence to the LOs (LO2 depends on the successful completion of LO1), LO2 can be thought of a sequence of events that start when LO1 is completed. In that way, an innovation project can be defined with a single LO spreadsheet that defines the LOs, the tasks to achieve the LOs, who will do the tasks, how success will be determined and when the work will be done. If you want to learn how to do innovation, learn how to use Learning Objectives.

There are more element of innovation to discuss, for example how to define customer segments, how to identify the most important problems, how to create creative solutions, how to estimate financial value of a project and how to go to market. But, those are for another post.

Until then, why not choose a project that scares you, define a small set of Learning Objectives and get going?

Image credit – JD Hancock

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski