Archive for the ‘Innovation’ Category

The Most Powerful Question

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Creativity, innovation and continuous improvement – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

And what about lifelong personal development? Yup – learning.

Learning results when a system behaves differently than your mental model. And there four ways make a system behave differently. First, give new inputs to an existing system. Second, exercise an existing system in a new way (for example, slow it down or speed it up.) Third, modify elements of the existing system. And fourth, create a new system. Simply put, if you want a system to behave differently, you’ve got to change something. But if you want to learn, the system must respond differently than you predict.

If a new system performs exactly like you expect, it isn’t a new system. You’re not trying hard enough.

When your prediction is different than how the system actually behaves, that is called error. Your mental model was wrong and now, based on the new test results, it’s less wrong. From a learning perspective, that’s progress. But when companies want predictable results delivered on a predictable timeline, error is the last thing they want. Think about how crazy that is. A company wants predictable progress but rejects the very thing that generates the learning. Without error there can be no learning.

If you don’t predict the results before you run the test, there can be no learning.

It’s exciting to create a new system and put it through its paces. But it’s not real progress – it’s just activity. The valuable part, the progress part, comes only when you have the discipline to write down what you think will happen before you run the test. It’s not glamorous, but without prediction there can be no error.

If there is no trial, there can be no error. And without error, there can be no learning.

Let’s face it, companies don’t make it easy for people to try new things. People don’t try new things because they are afraid to be judged negatively if it “doesn’t work.” But what does it mean when something doesn’t work? It means the response of the new system is different than predicted. And you know what that’s called, right? It’s called learning.

When people are afraid to try new things, they are afraid to learn.

We have a language problem that we must all work to change. When you hear, “That didn’t work.”, say “Wow, that’s great learning.” When teams are told projects must be “on time, on spec and on budget”, ask the question, “Doesn’t that mean we don’t want them to learn?”

But, the whole dynamic can change with this one simple question – “What did you learn?” At every meeting, ask “What did you learn?” At every design review, ask “What did you learn?” At every lunch, ask “What did you learn?” Any time you interact with someone you care about, find a way to ask, “What did you learn?”

And by asking this simple question, the learning will take care of itself.

Image credit m.shattock

Seeing What Isn’t There

It’s relatively straightforward to tell the difference between activities that are done well and those that are done poorly. Usually sub-par activities generate visual signals to warn us of their misbehavior. A bill isn’t paid, a legal document isn’t signed or the wrong parts are put in the box. Though the specifics vary with context, the problem child causes the work product to fall off the plate and make a mess on the floor.

It’s relatively straightforward to tell the difference between activities that are done well and those that are done poorly. Usually sub-par activities generate visual signals to warn us of their misbehavior. A bill isn’t paid, a legal document isn’t signed or the wrong parts are put in the box. Though the specifics vary with context, the problem child causes the work product to fall off the plate and make a mess on the floor.

We have tools to diagnose the fundamental behind the symptom. We can get to root cause. We know why the plate was dropped. We know how to define the corrective action and implement the control mechanism so it doesn’t happen again. We patch up the process and we’re up and running in no time. This works well when there’s a well-defined in place, when process is asked to do what it did last time, when the inputs are the same as last time and when the outputs are measured like they were last time.

However, this linear thinking works terribly when the context changes. When the old processes are asked to do new work, the work hits the floor like last time, but the reason it hits the floor is fundamentally different. This time, it’s not that an activity was done poorly. Rather, this time there’s something missing altogether. And this time our linear-thinker toolbox won’t cut it. Sure, we’ll try with all our Six Sigma might, but we won’t get to root cause. Six Sigma, lean and best practices can fix what’s broken, but none of them can see what isn’t there.

When the context changes radically, the work changes radically. New-to-company activities are required to get the new work done. New-to-industry tools are needed to create new value. And, sometimes, new-to-world thinking is the only thing that will do. The trick isn’t to define the new activity, choose the right new tool or come up with the new thinking. The trick is to recognize there’s something missing, to recognize there’s something not there, to recognize there’s a need for something new. Whether it’s an activity, a tool or new thinking, we’ve got to learn to see what’s not there.

Now the difficult part – how to recognize there’s something missing. You may think the challenging part is to figure out what’s needed to fill the void, but it isn’t. You can’t fill a hole until you see it as a hole. And once everyone agrees there’s a hole, it’s pretty easy to buy the shovels, truck in some dirt and get after it. But if don’t expect holes, you won’t see them. Sure, you’ll break your ankle, but you won’t see the hole for what it is.

If the work is new, look for what’s missing. If the problem is new, watch out for holes. If the customer is new, there will be holes. If the solution is new, there will be more holes.

When the work is new, you will twist your ankle. And when you do, grab the shovels and start to put in place what isn’t there.

Image credit – Tony Atler

On Gumption

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Doing new work takes gumption. But there are two problems with gumption. One, you’ve got to create it from within. Two, it takes a lot of energy to generate the gumption and to do that you’ve got to be physically fit and mentally grounded. Here are some words that may help.

Move from self-judging to self-loving. It makes a difference.

It’s never enough until you decide it’s enough. And when you do, you can be more beholden to yourself.

You already have what you’re looking for. Look inside.

Taking care of yourself isn’t selfish, it’s self-ful.

When in doubt, go outside.

You can’t believe in yourself without your consent.

Your well-being is your responsibility. And it’s time to be responsible.

When you move your body, your mind smiles.

With selfish, you take care of yourself at another’s expense. With self-ful, you take care of yourself because you’re full of self-love.

When in doubt, feel the doubt and do it anyway.

If you’re not taking care of yourself, understand what you’re putting in the way and then don’t do that anymore.

You can’t help others if you don’t take care of yourself.

If you struggle with taking care of yourself, pretend you’re someone else and do it for them.

Image credit — Ramón Portellano

Four Questions to Choose Innovation Projects

It’s a challenge to prioritize and choose innovation projects. There are open questions on the technology, the product/service, the customer, the price and sales volume. Other than that, things are pretty well defined.

It’s a challenge to prioritize and choose innovation projects. There are open questions on the technology, the product/service, the customer, the price and sales volume. Other than that, things are pretty well defined.

But with all that, you’ve still go to choose. Here are some questions that may help in your selection process

Is it big enough? The project will be long, expensive and difficult. And if the potential increase in sales is not big enough, the project is not worth starting. Think (Price – Cost) x Volume. Define a minimum viable increase in sales and bound it in time. For example, the minimum incremental sales is twenty five million dollars after five years in the market. If the project does not have the potential to meet those criteria, don’t do the project. The difficult question – How to estimate the incremental sales five years after launch? The difficult answer – Use your best judgement to estimate sales based on market size and review your assumptions and predictions with seasoned people you trust.

Why you? High growth markets/applications are attractive to everyone, including the big players and the well-funded start-ups. How does your company have an advantage over these tough competitors? What about your company sets you apart? Why will customers buy from you? If you don’t have good answers, don’t start the project. Instead, hold the work hostage and take the time to come up with good answers. If you come up with good answers, try to answer the next questions. If you don’t, choose another project.

How is it different? If the new technology can’t distinguish itself over existing alternatives, you don’t have a project worth starting. So, how is your new offering (the one you’re thinking about creating) better than the ones that can be purchased today? What’s the new value to the customer? Or, in the lingo of the day, what is the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP)? If there’s no DVP, there’s no project. If you’re not sure of the DVP, figure that out before investing in the project. If you have a DVP but aren’t sure it’s good enough, figure out how to test the DVP before bringing the DVP to life.

Is it possible? Usually, this is where everyone starts. But I’ve listed it last, and it seems backward. Would you rather spend a year making it work only to learn no one wants it, or would you rather spend a month to learn the market wants it then a year making it work? If you make it work and no one wants it, you’ve wasted a year. If, before you make it work, you learn no one wants it, you’ve spent a month learning the right thing and you haven’t spent a year working on the wrong thing. It feels unnatural to define the market need before making it work, but though it feels unnatural, it can block resources from working on the wrong projects.

There is no foolproof way to choose the best innovation projects, but these four questions go a long way. Create a one-page template with four sections to ask the questions and capture the answers. The sections without answers define the next work. Define the learning objectives and the learning activities and do the learning. Fill in the missing answers and you’re ready to compare one project to another.

Sort the projects large-to-small by Is it big enough? Then, rank the top three by Why you? and How is it different? Then, for the highest ranked project, do the work to answer Is it possible?

If it’s possible, commercialize. If it’s not, re-sort the remaining projects by Is it big enough? Why you? and How is it different? and learn if It is possible.

Image credit – Ben Francis

Four Pillars of Innovation – People, Learning, Judgment and Trust

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

Innovation is a hot topic. Everyone wants to do it. And everyone wants a simple process that works step-wise – first this, then that, then success.

But Innovation isn’t like that. I think it’s more effective to think of innovation as a result. Innovation as something that emerges from a group of people who are trying to make a difference. In that way, Innovation is a people process. And like with all processes that depend on people, the Innovation process is fluid, dynamic, complex, and context-specific.

Innovation isn’t sequential, it’s not linear and cannot be scripted.. There is no best way to do it, no best tool, no best training, and no best outcome. There is no way to predict where the process will take you. The only predictable thing is you’re better off doing it than not.

The key to Innovation is good judgment. And the key to good judgment is bad judgment. You’ve got to get things wrong before you know how to get them right. In the end, innovation comes down to maximizing the learning rate. And the teams with the highest learning rates are the teams that try the most things and use good judgement to decide what to try.

I used to take offense to the idea that trying the most things is the most effective way. But now, I believe it is. That is not to say it’s best to try everything. It’s best to try the most things that are coherent with the situation as it is, the market conditions as they are, the competitive landscape as we know it, and the the facts as we know them.

And there are ways to try things that are more effective than others. Think small, focused experiments driven by a formal learning objective and supported by repeatable measurement systems and formalized decision criteria. The best teams define end implement the tightest, smallest experiment to learn what needs to be learned. With no excess resources and no wasted time, the team wins runs a tight experiment, measures the feedback, and takes immediate action based on the experimental results.

In short, the team that runs the most effective experiments learns the most, and the team that learns the most wins.

It all comes down to choosing what to learn. Or, another way to look at it is choosing the right problems to solve. If you solve new problems, you’ll learn new things. And if you have the sightedness to choose the right problems, you learn the right new things.

Sightedness is a difficult thing to define and a more difficult thing to hone and improve. If you were charged with creating a new business in a new commercial space and the survival of the company depended on the success of the project, who would you want to choose the things to try? That person has sightedness.

Innovation is about people, learning, judgement and trust.

And innovation is more about why than how and more about who than what.

Image credit – Martin Nikolaj Christensen

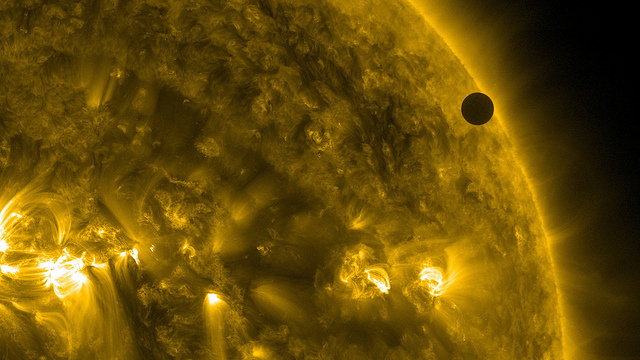

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

A culture that demands predictable results cannot innovate. No one will have the courage to do work with the requisite level of uncertainty and all the projects will build on what worked last time. The only predictable result – the recipe will be wildly successful right up until the wheels fall off.

You can’t do work in a new area and deliver predictable results on a predictable timetable. And if your boss asks you to do so, you’re working for the wrong person.

When it comes to innovation, “ecosystem,” as a word, is unskillful. It doesn’t bound or constrain, nor does it show the way. How about a map of the system as it is? How about defined boundaries? How about the system’s history? How about the interactions among the system elements? How about a fitness landscape and the system’s disposition? How about the system’s reason for being? The next evolution of the system is unpredictable, even if you call it an ecosystem.

If you can’t tolerate unpredictability, you can’t tolerate innovation.

Innovation isn’t about reducing risk. Innovation is about maximizing learning rate. And when all things go as predicted, the learning rate is zero. That’s right. Learning decreases when everything goes as planned. Are you sure you want predictable results?

Predictable growth in stock price can only come from smartly trying the right portfolio of unpredictable projects. That’s a wild notion.

Innovation runs on the thoughts, feelings, emotions and judgement of people and, therefore, cannot be predictable. And if you try to make it predictable, the best people, the people that know the drill, will leave.

The real question that connects innovation and predictability: How to set the causes and conditions for people to try things because the results are unpredictable?

With innovation, if you’re asking for predictability, you’re doing it wrong.

Image credit: NASA Goddard

How To Innovate Within a Successful Company

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

If you’re trying to innovate within a successful company, I have one word for you: Don’t.

You can’t compete with the successful business teams that pay the bills because paying the bills is too important. No one in their right mind should get in the way of paying them. And if you do put yourself in the way of the freight train that pays the bills you’ll get run over. If you want to live to fight another day, don’t do it.

If an established business has been growing three percent year-on-year, expect them to grow three percent next year. Sure, you can lather them in investment, but expect three and a half percent. And if they promise six percent, don’t believe them. In fairness, they truly expect they can grow six percent, but only because they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid.

Rule 1: If they’re drinking their own Cool-Aid, don’t believe them.

Without a cataclysmic problem that threatens the very existence of a successful company, it’s almost impossible to innovate within its four walls. If there’s no impending cataclysm, you have two choices: leave the four walls or don’t innovate.

It’s great to work at successful company because it has a recipe that worked. And it sucks to work at a successful company because everyone thinks that tired old recipe will work for the next ten years. Whether it will work for the next ten or it won’t, it’s still a miserable place to work if you want to try something new. Yes, I said miserable.

What’s the one thing a successful company needs? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo. What’s the one thing a successful company does not tolerate? A group of smart people who are actively dissatisfied with the status quo.

Some experts recommend leveraging (borrowing) resources from the established businesses and using them to innovate. If the established business catches wind that their borrowed resources will be used to displace the status quo, the resources will mysteriously disappear before the innovation project can start. Don’t try to borrow resources from established businesses and don’t believe the experts.

Instead of competing with established businesses for resources, resources for innovation should be allocated separately. Decide how much to spend on innovation and allocate the resources accordingly. And if the established businesses cry foul, let them.

Instead of borrowing resources from established businesses to innovate, increase funding to the innovation units and let them buy resources from outside companies. Let them pay companies to verify the Distinctive Value Proposition (DVP); let them pay outside companies to design the new product; let them pay outside companies to manufacture the new product; and let them pay outside companies to sell it. Sure, it will cost money, but with that money you will have resources that put their all into the design, manufacture and sale of the innovative new offering. All-in-all, it’s well worth the money.

Don’t fall into the trap of sharing resources, especially if the sharing is between established businesses and the innovative teams that are charged with displacing them. And don’t fall into the efficiency trap. Established businesses need efficiency, but innovative teams need effectiveness.

It’s not impossible to innovate within a successful company, but it is difficult. To make it easier, error on the side of doing innovation outside the four walls of success. It may be more expensive, but it will be far more effective. And it will be faster. Resources borrowed from other teams work the way they worked last time. And if they are borrowed from a successful team, they will work like a successful team. They will work with loss aversion. Instead of working to bring something to life they will work to prevent loss of what worked last time. And when doing work that’s new, that’s the wrong way to work.

The best way I know to do innovation within a successful company is to do it outside the successful company.

Image credit – David Doe

Important Questions for Innovation

Here are some important questions for innovation.

Here are some important questions for innovation.

What’s the Distinctive Value Proposition? The new offering must help the customer make progress. How does the customer benefit? How is their life made easier? How does this compare to the existing offerings? Summarize the difference on one page. If the innovation doesn’t help the customer make progress, it’s not an innovation.

Is it too big or too small? If the project could deliver sales growth that would dwarf the existing sales numbers for the company, the endeavor is likely too big. The company mindset and philosophy would have to be destroyed. Are you sure you’re up to the challenge? If the project could deliver only a small increase in sales, it’s likely not worth the time and expense. Think return on investment. There’s no right answer, but it’s important to ask the question and set the limits for too big and too small. If it could grow to 10% of today’s sales numbers, that’s probably about right.

Why us? There’s got to be a reason why you’re the right company to do this new work. List the company’s strengths that make the work possible. If you have several strengths that give you an advantage, that’s great. And if one of your weaknesses gives you an advantage, that works too. Step on the accelerator. If none of your strengths give you an advantage, choose another project.

How do we increase our learning rate? First thing, define Learning Objectives (LOs). And once defined, create a plan to achieve them quickly. Here’s a hint. Define what it takes to satisfy the LOs. Here’s another hind. Don’t build a physical prototype. Instead, create a website that describes the potential offering and its value proposition and ask people if they want to buy it. Collect the data and refine the offering based on your learning. Or, create a one-page sales tool and show it to ten potential customers. Define your learning and use the learning to decide what to do next.

Then what? If the first phase of the work is successful, there must be a then what. There must be an approved plan (funding, resources) for the second phase before the first phase starts. And the same thing goes for the follow-on phases. The easiest way to improve innovation effectiveness is avoid starting phase one of projects when their phase two is unfunded. The fastest innovation project is the wrong one that never starts.

How do we start? Define how much money you want to spend. Formalize your business objectives. Choose projects that could meet your business objectives. Free up your best people. Learn as quickly as you can.

Image credit — Alexander Henning Drachmann

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

The primary impediment to innovation is fear, and the prime directive of any innovation system should be to drive out fear.

A culture of accountability, implemented poorly, can inject fear and deter innovation. When the team is accountable to deliver on a project but are constrained to a fixed scope, a fixed launch date and resources, they will be afraid. Because they know that innovation requires new work and new work is inherently unpredictable, they rightly recognize the triple accountability – time, scope and resources – cannot be met. From the very first day of the project, they know they cannot be successful and are afraid of the consequences.

A culture of accountability can be adapted to innovation to reduce fear. Here’s one way. Keep the team small and keep them dedicated to a single innovation project. No resource sharing, no swapping and no double counting. Create tight time blocks with clear work objectives, where the team reports back on a fixed pitch (weekly, monthly). But make it clear that they can flex on scope and level of completeness. They should try to do all the work within the time constraints but they must know that it’s expected the scope will narrow or shift and the level of completeness will be governed by the time constraint. Tell them you believe in them and you trust them to do their best, then praise their good judgement at the review meeting at the end of the time block.

Innovation is about solving new problems, yet fear blocks teams from trying new things. Teams like to solve problems that are familiar because they have seen previous teams judged negatively for missing deadlines. Here’s the logic – we’d rather add too little novelty than be late. The team would love to solve new problems but their afraid, based on past projects, that they’ll be chastised for missing a completion date that’s disrespectful of the work content and level of novelty. If you want the team to solve new problems, give them the tools, time, training and a teacher so they can select different problems and solve them differently. Simply put – create the causes and conditions for fear to quietly slink away so innovation will flow.

Fear is the most powerful inhibitor. But before we can lessen the team’s fear we’ve got to recognize the causes and conditions that create it. Fear’s job is to keep us safe, to keep us away from situations that have been risky or dangerous. To do this, our bodies create deep memories of those dangerous or scary situations and creates fear when it recognizes similarities between the current situation and past dangerous situations. In that way, less fear is created if the current situation feels differently from situations of the past where people were judged negatively.

To understand the causes and conditions that create fear, look back at previous projects. Make a list of the projects where project members were judged negatively for things outside their control such as: arbitrary launch dates not bound by the work content, high risk levels driven by unjustifiable specifications, insufficient resources, inadequate tools, poor training and no teacher. And make a list of projects where team members were praised. For the projects that praised, write down attributes of those projects (e.g., high reuse, low technical risk) and their outcomes (e.g., on time, on cost). To reduce fear, the project team will bend new projects toward those attributes and outcomes. Do the same for projects that judged negatively for things outside the project teams’ control. To reduce fear, the future project teams will bend away from those attributes and outcomes.

Now the difficult parts. As a leader, it’s time to look inside. Make a list of your behaviors that set (or contributed to) causes and conditions that made it easy for the project team to be judged negatively for the wrong reasons. And then make a list of your new behaviors that will create future causes and conditions where people aren’t afraid to solve new problems in new ways.

Image credit — andrea floris

To figure out what’s next, define the system as it is.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every day starts and ends in the present. Sure, you can put yourself in the future and image what it could be or put yourself in the past and remember what was. But, neither domain is actionable. You can’t change the past, nor can you control the future. The only thing that’s actionable is the present.

Every morning your day starts with the body you have. You may have had a more pleasing body in the past, but that’s gone. You may have visions of changing your body into something else, but you don’t have that yet. What you do today is governed and enabled by your body as it is. If you try to lift three hundred pounds, your system as it is will either pick it up or it won’t.

Every morning your day starts with the mind you have. It may have been busy and distracted in the past and it may be calm and settled in the future, but that doesn’t matter. The only thing that matters is your mind as it is. If you respond kindly, today’s mind is responsible, and if your response is unkind, today’s mind system is the culprit. Like it or not, your thoughts, feelings and actions are the result of your mind as it is.

Change always starts with where you are, and the first step is unclear until you assess and define your systems as they are. If you haven’t worked out in five years, your first step is to see your doctor to get clearance (professional assessment) for your upcoming physical improvement plan. If you’ve run ten marathons over the last ten months, your first step may be to take a month off to recover. The right next step starts with where you are.

And it’s the same with your mind. If your mind is all over the place your likely first step is to learn how to help it settle down. And once it’s a little more settled, your next step may be to use more advanced methods to settle it further. And if you assess your mind and you see it needs more help than you can give it, your next step is to seek professional help. Again, your next step is defined by where you are.

And it’s the same with business. Every morning starts with the products and services you have. You can’t sell the obsolete products you had, nor can you sell the future services you may develop. You can only sell what you have. But, in parallel, you can create the next product or system. And to do that, the first step is to take a deep, dispassionate look at the system as it is. What does it do well? What does it do poorly? What can be built on and what can be discarded? There are a number of tools for this, but more important than the tools is to recognize that the next one starts with an assessment of the one you have.

If the existing system is young and immature, the first step is likely to nurture it and support it so it can grow out of its adolescence. But the first step is NOT to lift three hundred pounds because the system-as it is-can only lift fifty. If you lift too much too early, you’ll break its back.

If the existing system is in it’s prime and has been going to the gym regularly for the last five years, its ready for three hundred pounds. Go for it! But, in parallel, it’s time to start a new activity, one that will replace the weightlifting when the system can no longer lift like it used to. Maybe tennis? But start now because to get good at tennis requires new muscles and time.

And if the existing system is ready for retirement, retire it. Difficult to do, but once there’s public acknowledgement, the retirement will take care of itself.

If you want to know what’s next, define the system as it is. The next step will be clear.

And the best time to do it is now.

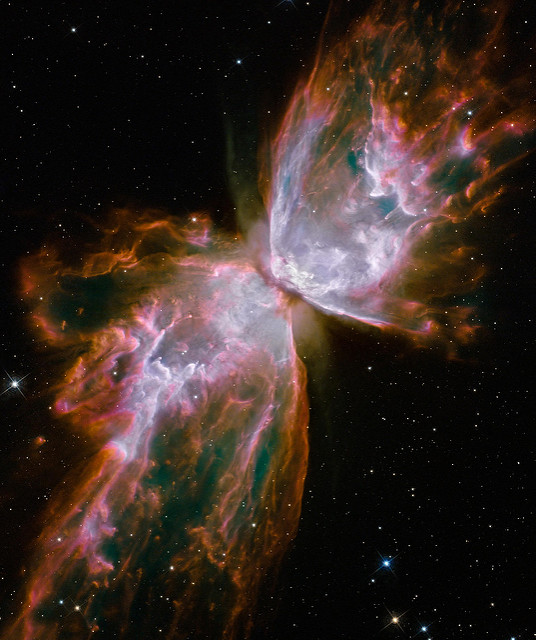

Image credit – NASA

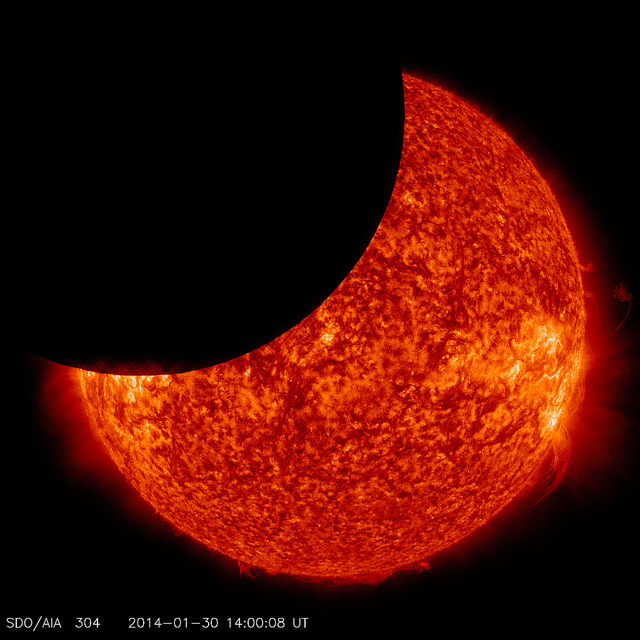

The right time horizon for technology development

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

Patents are the currency of technology and profits are the currency of business. And as it turns out, if you focus on creating technology you’ll get technology (and patents) and if you focus on profits you’ll get profits. But if no one buys your technology (in the form of the products or services that use it), you’ll go out of business. And if you focus exclusively on profits you won’t create technology and you’ll go out of business. I’m not sure which path is faster or more dangerous, but I don’t think it matters because either way you’re out of business.

It’s easy to measure the number of patents and easier to measure profits. But there’s a problem. Not all patents (technologies) are equal and not all profits are equal. You can have a stockpile of low-level patents that make small improvements to existing products/services and you can have a stockpile of profits generated by short-term business practices, both of which are far less valuable than they appear. If you measure the number of patents without evaluating the level of inventiveness, you’re running your business without a true understanding of how things really are. And if you’re looking at the pile of profits without evaluating the long-term viability of the engine that created them you’re likely living beyond your means.

In both cases, it’s important to be aware of your time horizon. You can create incremental technologies that create short term wins and consume all your resource so you can’t work on the longer-term technologies that reinvent your industry. And you can implement business practices that eliminate costs and squeeze customers for next-quarter sales at the expense of building trust-based engines of growth. It’s all about opportunity cost.

It’s easy to develop technologies and implement business processes for the short term. And it’s equally easy to invest in the long term at the expense of today’s bottom line and payroll. The trick is to balance short against long.

And for patents, to achieve the right balance rate your patents on the level of inventiveness.

Image credit – NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski