Archive for the ‘Innovation’ Category

An Injection Of Absurdity

Things are cyclic, but there seems to be no end to the crusade of continuous improvement. (Does anyone remember how the Crusades turned out?) If only to take the edge off, there needs to be an injection of absurdity.

There’s no pressure with absurdity – no one expects an absurd idea to work. If you ask for an innovative idea, you’ll likely get no response because there’s pressure from the expectation the innovative idea must be successful. And if you do get a response, you’ll likely get served a plain burrito of incremental improvement garnished with sour cream and guacamole to trick your eye and doused in hot sauce to trick your palate. If you ask for an absurd idea, you get laughter and something you’ve never heard before.

When drowning in the sea of standard work, it takes powerful mojo to save your soul. And the absurdity jetpack is the only thing I know with enough go to launch yourself to the uncharted oasis of new thinking. Immense force is needed because continuous improvement has serious mass – black hole mass. Like with light, a new idea gets pulled over the event horizon into the darkness of incremental thinking. But absurdity doesn’t care. It’s so far from the center lean’s pull is no match.

But to understand absurdity’s superpower is to understand what makes things absurd. Things are declared absurd when they cut against the grain of our success. It’s too scary to look into the bright sun of our experiences, so instead of questioning their validity and applicability, the idea is deemed absurd. But what if the rules have changed and the fundamentals of last year’s success no longer apply? What if the absurd idea actually fits with the new normal? In a strange Copernican switch, holding onto to what worked becomes absurd.

Absurd ideas sometimes don’t pan out. But sometimes they do. When someone laughs at your idea, take note – you may be on to something. Consider the laughter an artifact of misunderstanding, and consider the misunderstanding a leading indicator of the opportunity to reset customer expectations. And if someone calls your idea absurd, give them a big hug of thanks, and get busy figuring out how to build a new business around it.

Look Inside, Take New Action, Speak New Ideas.

There’s a lot buzz around reinvention and innovation. There are countless articles on tools and best practices; many books on the best organizational structure, and plenty on roles and responsibilities. There’s so much stuff that it’s tough to define what’s missing, even when what’s missing is the most important part. Whether its creativity, innovation, or doing new, the most important and missing element is your behavior.

There’s a lot buzz around reinvention and innovation. There are countless articles on tools and best practices; many books on the best organizational structure, and plenty on roles and responsibilities. There’s so much stuff that it’s tough to define what’s missing, even when what’s missing is the most important part. Whether its creativity, innovation, or doing new, the most important and missing element is your behavior.

Two simple rules to live by: 1) Look inside. 2) Then, change your behavior.

To improve innovation, people typically look to nouns for the answers – meeting rooms, work spaces, bean bag chairs, and tools, tools, tools. But the answer isn’t nouns, the answer is verbs. Verbs are action words, things you do, behaviors. And there are two behaviors that make the difference: 1.) Take new action. 2) Speak new ideas.

To take new action, you’ve got to be perceptive, perceptive about what’s blocking you from taking new action. The biggest blocker of new action is anxiety, and you must learn what anxiety feels like. Thought the brain makes anxiety, it’s easiest to perceive anxiety in the body. For me, anxiety manifests as a cold sinking feeling in my chest. When I recognize the coldness, I know I’m anxious. Your task is to figure out your anxiety’s telltale heart.

To learn what anxiety feels like, you’ve got to slow down enough to actually feel. The easiest way for overbooked high performers to make time to slow down is to schedule a recurring meeting with yourself. Schedule a recurring 15 minute meeting (Daily is best.) in a quiet place. No laptop, no cell phone, no paper, no pencil, no headphones – just you and quiet sitting together. Do this for a week and you’ll learn what anxiety feels like.

To take new action, you’ve got to be receptive, receptive to the anxiety. You’ll naturally judge anxiety as bad, but that’s got to change. Anxiety isn’t bad, it’s just unpleasant. And in this case, anxiety is an indicator of importance. When you block yourself from taking an important action, you create anxiety. So when you feel anxiety, be receptive – it’s your body telling you the yet-to-be-taken action is important.

After receptive, it’s time to be introspective. Look inside, turn toward your anxiety, and understand why the task is important. Typically it’s important because it threatens the status quo. Maybe it would dismantle your business model, or maybe it will unglue the foundation of your company, or maybe something smaller yet threatening. Once you understand its importance, it’s time to use the importance as the forcing function to start the task first thing tomorrow morning.

The second magic behavior is to speak new ideas. To speak new ideas, you’ve got to be perceptive to the reason you self censor. Before you can un-censor, you’ve got to be aware you self censor. It’s time to get in touch with your unsaid ideas. Now that you no longer need the 15 minute meeting for taking new action, change the agenda to speaking new ideas. Again, no laptop, cell phone, and headphones, but this time it’s you and quiet figuring out what if feels like right before you self-censor.

In your meeting, remember back to a brainstorming session when you had a crazy idea, but decided to bury it. Get in touch with what your body felt like as you stopped yourself from speaking your crazy idea. That’s the feeling you want to be aware of because it’s a leading indicator of your self censoring behavior.

Next, it’s time to be receptive, receptive to the idea that just as you choose to self censor, you can choose to stop your self censorship, and receptive to the idea that there’s a deep reason for your behavior.

Now, it’s on to introspective. When you have a crazy idea, why do you keep your mouth shut? Turn toward the behavior and you may see you self censor because you don’t want to be judged. If you utter a crazy idea, you may be afraid you’ll be judged as crazy or incompetent. Likely, you’re afraid saying your idea out loud will change something – what other people think of you.

There are a couple important notions to help you battle your fear of judgment. First, you are not your ideas. You can have wild ideas and be highly competent, highly valued, and a good person. Second, other people’s judgment is about them, not you. They are threatened by your idea, and instead of looking inside, they protect themselves by trying to knock you down.

There’s a lot of nuance and complexity around creativity and innovation, but it doesn’t have to be that way. Really, it comes down to four things: own your behavior, look inside, take new action, and speak new ideas. It’s that simple.

The Half-Life of Our Maps

The early explorers had maps, but they were wrong – sea monsters, missing continents, and the home country at the center. Wrong, yes, but the best maps of their day. The early maps weren’t right because the territory was new, and you can expect the same today. When you work in new territory, your maps are wrong.

The early explorers had maps, but they were wrong – sea monsters, missing continents, and the home country at the center. Wrong, yes, but the best maps of their day. The early maps weren’t right because the territory was new, and you can expect the same today. When you work in new territory, your maps are wrong.

As the explorers’ adventures radiated further from home, they learned and their maps improved. But still, the maps were best close to home and diverged at the fringes. And over the centuries the radius of rightness grew and the maps converged on the territory. And with today’s GPS technology, maps are dead on. The system worked – a complete map of everything.

Today you have your maps of your business environment and the underlying fundementals that ground them. Like the explorers you built them over time and checked them along the way. They’re not perfect (more right close to home) but they’re good. You mapped the rocks, depths, and tides around the trade routes and you stay the course because the routes have delivered profits and they’re safe. You can sail them in your sleep, and sometimes you do.

But there’s a fundamental difference between the explorers’ maps and yours – their territory, the physical territory, never changed, but yours is in constant flux. The business trade winds shift as new technologies develop; the size of continents change as developing countries develop; and new rocks grow from the sea floor as competitors up their game. Just when your maps match the territory, the territory changes around you and diverges from your maps, and your maps become old. The problem is the maps don’t look different. Yes, they’re still the same maps that guided you safely along your journey, but they no longer will keep you safely off the rocks and out of the Doldrums.

But as a new age explorer there’s hope. With a healthy skepticism of your maps, frequently climb the mast and from the crow’s nest scan the horizon for faint signs of trouble. Like a thunder storm just below the horizon, you may not hear trouble coming, but there’ll be dull telltale flashes that flicker in your eyepiece. Not all the crew will see them, or want to see them, or want to believe you saw them, so be prepared when your report goes unheeded and your ship sales into the eye of the storm.

Weak signals are troubling for several reasons. They’re infrequent and unpredictable which makes them hard to chart, and they’re weak so they’re tough to hear and interpret. But worst of all is their growth curve. Weak signals stay weak for a long time until they don’t, and when they grow, they grow quickly. A storm just over the horizon gives weak signals right up until you sail into gale force winds strong enough to capsize the largest ships.

Maps are wrong when the territory is new, and get more right as you learn; but as the territory changes and your learning doesn’t, maps devolve back to their natural wrongness. But, still, they’re helpful. And they’re more helpful when you remember they have a natural half-life.

My grandfather was in the Navy in World War II, though he could never bring himself to talk about it. However, there was one thing he told me, a simple saying he said kept him safe:

Red skies at night, sailor’s delight; red skies in morninng, sailor takes warning.

I think he knew the importance of staying aware of the changing territory.

Bridging The Chasm Between Technologists and Marketers

What’s a new market worth without a new technology to capture it? The same as a new technology without a new market – not much. Technology and market are a matched set, but not like peanut butter and jelly, (With enough milk, a peanut butter sandwich isn’t bad.) rather, more like H2 and O: whether it’s H2 without O or O without H2 – there’s no water. With technology and market, there’s no partial credit – there’s nothing without both.

What’s a new market worth without a new technology to capture it? The same as a new technology without a new market – not much. Technology and market are a matched set, but not like peanut butter and jelly, (With enough milk, a peanut butter sandwich isn’t bad.) rather, more like H2 and O: whether it’s H2 without O or O without H2 – there’s no water. With technology and market, there’s no partial credit – there’s nothing without both.

You’d think with such a tight coupling, market and technology would be highly coordinated, but that’s not the case. There’s a deep organizational chasm between them. But worse, each has their own language, tools, and processes. Plain and simple, the two organizations don’t know how to talk to each other, and the result is the wrong technology for the right market (if you’re a marketer) or the right technology for the wrong market (if you’re a technologist.) Both ways, customers suffer and so do business results.

The biggest difference, however, is around customers. Where marketers pull, technologists push – can’t be more different than that. But neither is right, both are. There’s no sense arguing which is more important, which is right, or which worked better last time because you need both. No partial credit.

If you speak only French and have a meeting with someone who speaks only Portuguese, well, that’s like meeting between marketers and technologists. Both are busy as can be, and neither knows what the other is doing. There’s a huge need for translators – marketers that speak technologist and technologists that talk marketing. But how to develop them?

The first step is to develop a common understanding of why. Why do you want to develop the new market? Why hasn’t anyone been able to create the new market? Why can’t we develop a new technology to make it happen? It’s a good start when both sides have a common understanding of the whys.

To transcend the language barrier, don’t use words, use video. To help technologists understand unmet customer needs, show them a video of a real customer in action, a real customer with a real problem. No words, no sales pitch, just show the video. (Put your hand over your mouth if you have to.) Show them how the work is done, and straight away they’ll scurry to the lab and create the right new technologies to help you crack the new market. Technologists don’t believe marketers; technologists believe their own eyes, so let them.

To help marketers understand technology, don’t use words, use live demos. Technologists – set up a live demo to show what the technology can do. Put the marketer in front of the technology and let them drive, but you can’t tell them how to drive. You too must put your hand over your mouth. Let them understand it the way they want to understand it, the way a customer would understand it. They won’t use it the way you think they should, they’ll use it like a customer. Marketers don’t understand technology, they understand their own eyes, so let them.

And after the videos and the live demos, it’s time to agree on a customer surrogate. The customer surrogate usually takes the form of a fully defined test protocol and fully defined test results. And when done well, the surrogate generates test results that correlate with goodness needed to crack the new market. As the surrogate’s test results increase, so does goodness (as the customer defines it.) Instead of using words to agree on what the new technology must do, agreement is grounded in a well defined test protocol and a clear, repeatable set of test results. Everyone can use their eyes to watch the actual hardware being tested and see the actual test results. No words.

To close the loop and determine if everyone is on the same page, ask the marketers and technologist to co-create the marketing brochure for the new product. Since the brochure is written for the customer, it forces the team use plain language which can be understood by all. No marketing jargon or engineering speak – just plain language.

And now, with the marketing brochure written, it’s time to start creating the right new market and the right new technology.

Photo credit – TORLEY.

Breaching the Wall of Denial

To do innovation, you’ve got to be all in, both physically and mentally. And to be all in, you’ve got to bust through one of the most powerful forces on the planet – denial.

Denial exists because seeing things as they are is scary. Denial prevents you from seeing problems so you can protect yourself from things that are scary. But the dark consequence of its protection is you block yourself from doing new things, from doing innovation. Because you deny the truth of how things are, you don’t acknowledge problems; and because you don’t admit there’s a problem, there’s no forcing function for doing the difficult work of innovation.

Problems threaten, but problems have power. Effectively harnessed, problems can be powerful enough to bust through denial. But before you can grab them by the mane, you have to be emotionally strong enough to see them. You have to be ready to see them; you have to be in the right mindset to see them; and because your organization will try to tear you down when you point to a big problem, you have to have a high self worth to stand tall.

Starting an innovation project is the toughest part and most important part. Starting is the most important because 100% of all innovations projects that don’t start, fail. Those aren’t good odds. And because starting is so emotionally difficult, people with high self worth are vital. Plain and simple: they’re strong enough to start.

Denial helps you stay in your comfort zone, but that’s precisely where you don’t want to be. To change and grow you’ve got to breach the wall of denial, and climb out of your comfort zone.

Tracking Toward The Future

It’s difficult to do something for the first time. Whether it’s a new approach, a new technology, or a new campaign, the mass of the past pulls our behavior back toward itself. And sadly, whether the past has been successful or not, its mass, and therefore it’s pull, are about the same. The past keeps us along the track of sameness.

It’s difficult to do something for the first time. Whether it’s a new approach, a new technology, or a new campaign, the mass of the past pulls our behavior back toward itself. And sadly, whether the past has been successful or not, its mass, and therefore it’s pull, are about the same. The past keeps us along the track of sameness.

Trains have tracks to enable them to move efficiently (cost per mile), and when you want to go where the train is heading, it’s all good. But when the tracks are going to the wrong destination, all that efficiency comes at the expense of effectiveness. Like we’re on rails, company history keeps us on track, even if it’s time for a new direction.

The best trains run on a ritualistic schedule. People queue up at same time every morning to meet their same predictable behemoth, and take comfort in slinking into their regular seats and turning off their brains. And this is the train’s trick. It uses its regularity to lull riders into a hazy state of non-thinking – get on, sit down, and I’ll get your there – to blind passengers from seeing its highly limited timetable and its extreme inflexibility. The train doesn’t want us to recognize that it’s not really about where the train wants to go.

Trains are powerful in their own right, but their real muscle comes from the immense sunk cost of their infrastructure. Previous generations invested billions in train stations, repair facilities, tight integration with bus lines, and the tracks, and it takes extreme strength of character to propose a new direction that doesn’t make use of the old, tired infrastructure that’s already paid for. Any new direction that requires a whole new infrastructure is a tough sell, and that’s why the best new directions transcend infrastructure altogether. But for those new directions that require new infrastructure, the only way to go is a modular approach that takes the right size bites.

Our worn tracks were laid in a bygone era, and the important destinations of yesteryear are no longer relevant. It’s no longer viable to go where the train wants; we must go where we want.

It Can’t Be Innovation If…

Companies strive for predictability, yet if it’s predictable, it cannot be innovation.

We seek comfort in our work, but if it’s comfortable it can’t be innovation.

Businesses like to grow by selling more to the customers we have, but if existing customers can recognize it, it can’t be innovation.

We want to meet year end numbers, but if the project will generate profit in the year it begins, it can’t be innovation.

We love our standardized processes, but if it’s standard, it cannot be innovation.

If there’s consensus, it’s not innovation.

If the project isn’t wreaking havoc with your organizational norms, it can’t be innovation.

If the market already exists, it can’t be innovation.

If you’ve done it before, it can’t be innovation.

If you are following a best practice, it can’t be innovation.

If there’s a high probability it will work, it can’t be innovation.

If people aren’t threatened, it can’t be innovation.

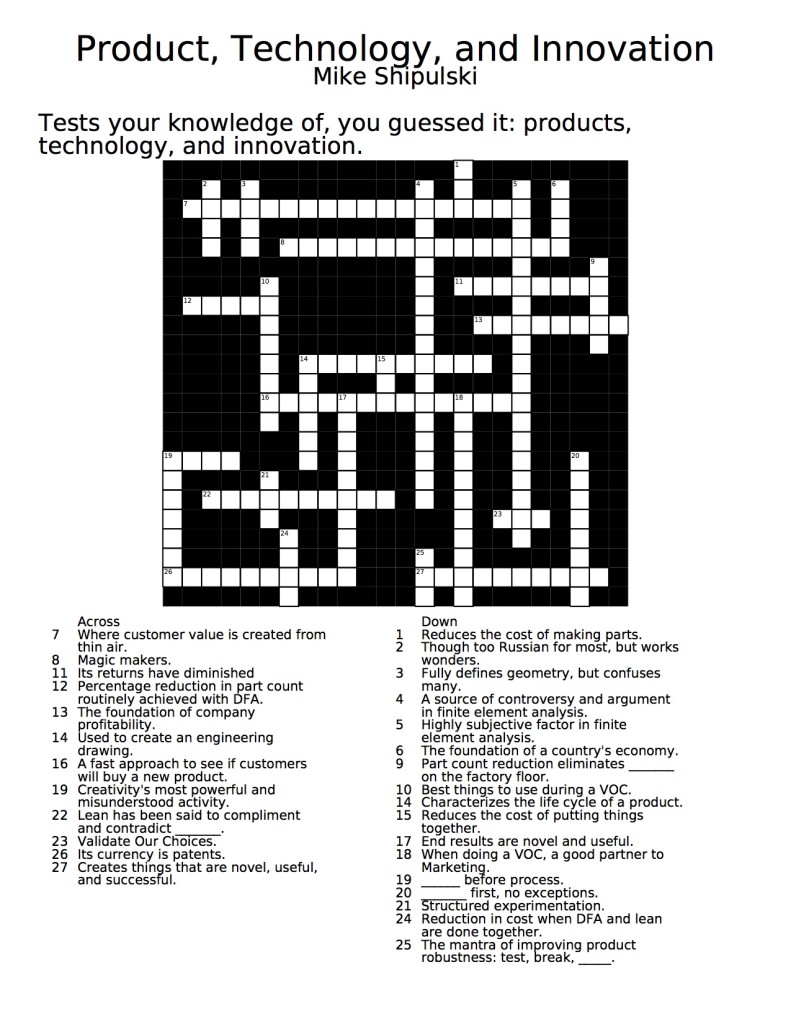

Crossword Puzzle – Product, Technology, Innovation

Here’s something a little different – a crossword puzzle to test your knowledge on products, technology, and innovation. Complete the puzzle using the image below, or download it (and answer key) using the green arrows below, and take your time with it over the Thanksgiving holiday.

[wpdm_file id=5]

[wpdm_file id=4]

Less Before More – Innovation’s Little Secret

The natural mindset of innovation is more-centric. More throughput; more performance; more features and functions; more services; more sales regions and markets; more applications; more of what worked last time. With innovation, we naturally gravitate toward more.

The natural mindset of innovation is more-centric. More throughput; more performance; more features and functions; more services; more sales regions and markets; more applications; more of what worked last time. With innovation, we naturally gravitate toward more.

There are two flavors of more, one better than the other. The better brother is more that does something for the first time. For example, the addition of the first airbags to automobiles – clearly an addition (previous vehicles had none) and clearly a meaningful innovation. More people survived car crashes because of the new airbags. This something-from-nothing more is magic, innovative, and scarce.

Most more work is of a lesser class – the more-of-what-is class. Where the first airbags were amazing, moving from eight airbags to nine – not so much. When the first safety razors replaced straight razors, they virtually eliminated fatal and almost fatal injuries, which was a big deal; but when the third and fourth blades were added, it was more trivial than magical. It was more for more’s sake; it was more because we didn’t know what else to do.

While more is more natural, less is more powerful. The Innovator’s Dilemma clearly called out the power of less. When the long-in-the-tooth S-curve flattens, Christensen says to look down, to look down and create technologies that do less. Actually, he tells us someone will give ground on the very thing that built the venerable S-curve to make possible a done-for-the-first-time innovation. He goes on to say you might as well be the one to dismantle your S-curve before a somebody else beats you to it. Yes, a wonderful way to realize the juciest innovation is with a less-centric mindset.

The LED revolution was made possible with less-centric thinking. As the incandescent S-curve hit puberty, wattage climbed and more powerful lights became cost effective; and as it matured, output per unit cost increased. More on more. And looking down from the graying S-curve was the lowly LED, whose output was far, far less.

But what the LED gave up in output it gained in less power draw and smaller size. As it turned out, there was a need for light where there had been none – in highly mobile applications where less size and weight were prized. And in these new applications, there was just a wisp of available power, and incandesent’s power draw was too much. If only there was a technology with less power draw.

But at the start, volumes for LEDs were far less than incandesent’s; profit margin was less; and most importantly, their output was far less than any self-respecting lightbulb. From on high, LEDs weren’t real lights; they were toys that would never amount to anything.

You can break intellectual inertia around more, and good things will happen. New design space is created from thin air once you are forced from the familiar. But it takes force. Creative use of constraints can help.

Get a small team together and creatively construct constraints that outlaw the goodness that makes your product great. The incandescent group’s constraint could be: create a light source that must make far less light. The automotive group’s constraint: create a vehicle that must have less range – battery powered cars. The smartphone group: create a smartphone with the fewest functions – wrist phone without Blutooth to something in your pocket , longer battery life, phone in the ear, phone in your eyeglasses.

Less is unnatural, and less is scary. The fear is your customers will get less and they won’t like it. But don’t be afraid because you’re going to sell to altogether different customers in altogether markets and applications. And fear not, because to those new customers you’ll sell more, not less. You’ll sell them something that’s the first of its kind, something that does more of what hasn’t been done before. It may do only a little bit of that something, but that’s far more than not being able to do it all.

Don’t tell anyone, but the next level of more will come from less.

Choose Yourself

We’ve been conditioned to ask for direction; to ask for a plan; and ask for permission. But those ways no longer apply. Today that old behavior puts you at the front of the peloton in the great race to the bottom.

We’ve been conditioned to ask for direction; to ask for a plan; and ask for permission. But those ways no longer apply. Today that old behavior puts you at the front of the peloton in the great race to the bottom.

The old ways are gone.

Today’s new ways: propose a direction (better yet, test one out on a small scale); create and present a radical plan of your own (or better, on the smallest of scales test the novel aspects and present your learning); and demonstrate you deserve permission by initiating activity on something that will obsolete the very thing responsible for your success.

People that wait for someone to give them direction are now a commodity, and with commodities it always ends in the death spiral of low cost providers putting each other out of business. As businesses are waist deep in proposals to double-down on what hasn’t worked and are choking on their flattened S-curves, there’s a huge opportunity for people that have the courage to try new things on their own. Today, if you initiate you’ll differentiate.

[This is where you say to yourself – I’ve already got too much on my plate, and I don’t have the time or budget to do more (and unsanctioned) work. And this is where I tell you your old job is already gone, and you might as well try something innovative. It’s time to grab the defibrillator and jolt your company out of its flatline. ]

It’s time to respect your gut and run a low cost, micro-experiment to test your laughable idea. (And because you’ll keep the cost low, no one will know when it doesn’t go as you thought. [They never do.]) It’s time for an underground meeting with your trusted band of dissidents to plan and run your pico-experiment that could turn your industry upside down. It’s time to channel your inner kindergartener and micro-test the impossible.

It’s time to choose yourself.

Moving From Kryptonite To Spinach

With websites, e-books, old fashioned books, Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, and blogs, there’s a seemingly limitless flood of information on every facet of business. There are heaps on innovation, new product development, lean, sales and marketing, manufacturing, and strategy; and within each there are elements and sub elements that fan out with multiple approaches.

With websites, e-books, old fashioned books, Twitter, LinkedIn, Facebook, and blogs, there’s a seemingly limitless flood of information on every facet of business. There are heaps on innovation, new product development, lean, sales and marketing, manufacturing, and strategy; and within each there are elements and sub elements that fan out with multiple approaches.

With today’s search engines and bots to automatically scan the horizon, it’s pretty easy to find what you’re looking for especially as you go narrow and deep. If you want to find best practices for reducing time-to-market for products designed in the US and manufactured in China, ask Google and she’ll tell you instantly. If you’re looking to improve marketing of healthcare products for the 20 to 40 year old demographic of the developing world, just ask Siri.

It’s now easy to separate the good stuff from the chaff and focus narrowly on your agenda. It’s like you have the capability dig into a box of a thousand puzzle pieces and pull out the very one you’re looking for. Finding the right puzzle piece is no longer the problem, the problem now is figuring out how they all fit together.

What holds the pieces together? What’s the common thread that winds through innovation, sales, marketing, and manufacturing? What is the backplane behind all this business stuff?

The backplane, and first fundamental, is product.

Every group has their unique work, and it’s all important – and product cuts across all of it. You innovate on product; sell product; manufacture product; service product. The shared context is the product. And I think there’s opportunity to use the shared context, this product lens, to open up design space of all our disciplines. For example how can the product change to make possible new and better marketing? How can the product change to radically simplify manufacturing? How can the product change so sales can tell the story they always wanted to tell? What innovation work must be done to create the product we all want?

In-discipline improvements have been good, but it’s time to take a step back and figure out how to create disruptive in-discipline innovations; to eliminate big discontinuities that cut across disciplines; and to establish multidisciplinary linkages and alignment to power the next evolution of our businesses. New design space is needed, and the product backplane can help.

Use the product lens to look along the backplane and see how changes in the product can bridge discontinuities across sales, marketing, and engineering. Use the common context of product to link revolutionary factory simplification to changes in the product. Use new sensors in the product to enable a new business model based on predictive maintenance. Let your imagination guide you.

It’s time to see the product for more than what it does and what it looks like. It’s time to see it as Superman’s kryptonite that constrains and limits all we do that can become Popeye’s spinach that can strengthen us to overpower all obstacles.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski