Archive for the ‘Innovation’ Category

Compete with No One

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

Today’s commercial environment is fierce. All companies have aggressive growth objectives that must be achieved at all costs. But there’s a problem – within any industry, when the growth goals are summed across competitors, there are simply too few customers to support everyone’s growth goals. Said another way, there are too many competitors trying to eat the same pie. In most industries it’s fierce hand-to-hand combat for single-point market share gains, and it’s a zero sum game – my gain comes at your loss. Companies surge against each other and bloody skirmishes break out over small slivers of the same pie.

The apex of this glorious battle is reached when companies no longer have points of differentiation and resort to competing on price. This is akin to attrition warfare where heavy casualties are taken on both sides until the loser closes its doors and the winner emerges victorious and emaciated. This race to the bottom can only end one way – badly for everyone.

Trench warfare is no way for a company to succeed, and it’s time for a better way. Instead of competing head-to-head, it’s time to compete with no one.

To start, define the operating envelope (range of inputs and outputs) for all the products in the market of interest. Once defined, this operating envelope is off limits and the new product must operate outside the established design space. By definition, because the new product will operate with input conditions that no one else’s can and generate outputs no one else can, the product will compete with no one.

In a no-to-yes way, where everyone’s product says no, yours is reinvented to say yes. You sell to customers no one else can; you sell into applications no one else can; you sell functions no one else can. And in a wicked googly way, you say no to functions that no one else would dare. You define the boundary and operate outside it like no one else can.

Competing against no one is a great place to be – it’s as good as trench warfare is bad – but no one goes there. It’s straightforward to define the operating windows of products, and, once define it’s straightforward to get the engineers to design outside the window. The hard part is the market/customer part. For products that operate outside the conventional window, the sales figures are the lowest they can be (zero) and there are just as many customers (none). This generates extreme stress within the organization. The knee-jerk reaction is to assign the wrong root cause to the non-existent sales. The mistake – “No one sells products like that today, so there’s no market there.” The truth – “No one sells products like that today because no one on the planet makes a product like that today.”

Once that Gordian knot is unwound, it’s time for the marketing community to put their careers on the line. It’s time to push the organization toward the scary abyss of what could be very large new market, a market where the only competition would be no one. And this is the real hard part – balancing the risk of a non-existent market with the reward of a whole new market which you’d call your own.

If slugging it out with tenacious competitors is getting old, maybe it’s time to compete with no one. It’s a different battle with different rules. With the old slug-it-out war of attrition, there’s certainty in how things will go – it’s certain the herd will be thinned and it’s certain there’ll be heavy casualties on all fronts. With new compete-with-no-one there’s uncertainty at every turn, and excitement. It’s a conflict governed by flexibility, adaptability, maneuverability and rapid learning. Small teams work in a loosely coordinated way to test and probe through customer-technology learning loops using rough prototypes and good judgement.

It’s not practical to stop altogether with the traditional market share campaign – it pays the bills – but it is practical to make small bets on smart people who believe new markets are out there. If you’re lucky enough to have folks willing to put their careers on the line, competing with no one is a great way to create new markets and secure growth for future generations.

Image credit – mae noelle

Purposeful Violation of the Prime Directive

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

In Star Trek, the Prime Directive is the over-arching principle for The United Federation of Planets. The intent of the Prime Directive is to let a sentient species live in accordance with its normal cultural evolution. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if Star Fleet personnel know the end is near for the sentient species, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

But what does it mean to “live in accordance with the normal cultural evolution?” To me it means “preserve the status quo.” In other words, the Prime Directive says – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Though today’s business environment isn’t Star Trek and none of us work for Star Fleet, there is a Prime Directive of sorts. Today’s Prime Directive deals not with sentient species and their cultures but with companies and their business models, and its intent is to let a company live in accordance with the normal evolution of its business model. And the rules are pretty simple – do whatever you want as long as you don’t violate the Prime Directive. Even if company leaders know the end is near for the business model, they can do nothing to save it from ruin.

Business models, and their decrepit value propositions propping them up, don’t evolve. They stay just as they are. From inside the company the business model and value proposition are the very things that provide sustenance (profitability). They are known and they are safe – far safer than something new – and employees defend them as diligently as Captain Kirk defends his Prime Directive. With regard to business models, “to live in accordance with its natural evolution” is to preserve the status quo until it goes belly up. Today’s Prime Directive is the same as Star Trek’s – don’t do anything to challenge or change the status quo.

Innovation brings to life things that are novel, useful, and successful. And because novel is the same as different, innovation demands complete violation of today’s Prime Directive. For innovators to be successful, they must blow up the very things the company holds dear – the declining business model and its long-in-the-tooth value proposition.

The best way to help innovators do their work is to provide them phasers so they can shoot those in the way of progress, but even the most progressive HR departments don’t yet sanction phasers, even when set to “stun”. The next best way is to educate the company on why innovation is important. Company leaders must clearly articulate that business models have a finite life expectancy (measured in years, not decades) and that it’s the company’s obligation to disrupt and displace it.them.

The Prime Directive has a valuable place in business because it preserves what works, but it needs to be amended for innovation. And until an amendment is signed into law, company leaders must sanction purposeful violation of the Prime Directive and look the other way when they hear the shrill ring a phaser emanating from the labs.

Image credit – svenwerk

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

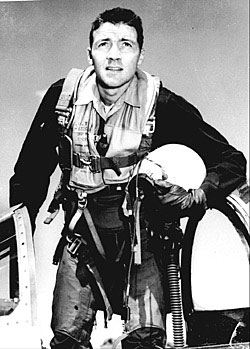

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

The Lonely Chief Innovation Officer

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

Chief Innovation Officer is a glorious title, and seems like the best job imaginable. Just imagine – every-day-all-day it’s: think good thoughts, imagine the future, and bring new things to life. Sounds wonderful, but more than anything, it’s a lonely slog.

In theory it’s a great idea – help the company realize (and acknowledge) what it’s doing wrong (and has been for a long time now), take resources from powerful business units and move them to a fledgling business units that don’t yet sell anything, and do it without creating conflict. Sounds fun, doesn’t it?

Though there are several common problems with the role of Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), the most significant structural issue, by far, is the CIO has no direct control over how resources are allocated. Innovation creates products, services and business models that are novel, useful and successful. That means innovation starts with ideas and ends with commercialized products and services. And no getting around it, this work requires resources. The CIO is charged with making innovation come to be, yet authority to allocate resources is withheld. If you’re thinking about hiring a Chief Innovation Officer, here’s a rule to live by:

If resources are not moved to projects that generate novel ideas, convert those ideas into crazy prototypes and then into magical products that sell like hotcakes, even the best Chief Innovation Officer will be fired within two years.

Structurally, I think it’s best if the powerful business units (who control the resources) are charged with innovation and the CIO is charged with helping them. The CIO helps the business units create a forward-looking mindset, helps bring new thinking into the old equation, and provides subject matter expertise from outside the company. While this addresses the main structural issue, it does not address the loneliness.

The CIO’s view of what worked is diametrically opposed to those that made it happen. Where the business units want to do more of what worked, the CIO wants to dismantle the engine of success. Where the engineers that designed the last product want to do wring out more goodness out of the aging hulk that is your best product, the CIO wants to obsolete it. Where the business units see the tried-and-true business model as the recipe for success, the CIO sees it as a tired old cowpath leading to the same old dried up watering hole. If this sounds lonely, it’s because it is.

To combat this fundamental loneliness, the CIO needs to become part of a small group of trusted CIOs from non-competing companies. (NDAs required, of course.) The group provides its members much needed perspective, understanding and support. At the first meeting the CIO is comforted by the fact that loneliness is just part of the equation and, going forward, no longer takes it personally. Here are some example deliverables for the group.

Identify the person who can allocate resources and put together a plan to help that person have a big problem (no incentive compensation?) if results from the innovation work are not realized.

Make a list of the active, staffed technology projects and categorize them as: improving what already exists, no-to-yes (make a product/service do something it cannot), or yes-to-no (eliminate functionality to radically reduce the cost signature and create new markets).

For the active, staffed projects, define the market-customer-partner assumptions (market segment, sales volume, price, cost, distribution and sales models) and create a plan to validate (or invalidate) them.

To the person with the resources and the problem if the innovation work fizzles, present the portfolio of the active, staffed projects and its validated roll-up of net profit, and ask if portfolio meets the growth objectives for the company. If yes, help the business execute the projects and launch the products/services. If no, put a plan together to run Innovation Burst Events (IBEs) to come up with more creative ideas that will close the gap.

The burning question is – How to go about creating a CIO group from scratch? For that, you need to find the right impresario that can pull together a seemingly disparate group of highly talented CIOs, help them forge a trusting relationship and bring them the new thinking they need.

Finding someone like that may be the toughest thing of all.

Image credit – Giant Humanitarian Robot.

Innovation is a Choice

A body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless it’s perturbed by an external force. And, it’s the same with people – we keep doing what we’re doing until there’s a reason we cannot. If it worked, there’s no external force to create changes, so we do more of what worked. If it didn’t work, while that should result in an external force strong enough to create change, often it doesn’t and we try more of what didn’t work, but try it harder. Though the scenarios are different, in both the external force is insufficient to create new behavior.

A body in motion tends to stay in motion, unless it’s perturbed by an external force. And, it’s the same with people – we keep doing what we’re doing until there’s a reason we cannot. If it worked, there’s no external force to create changes, so we do more of what worked. If it didn’t work, while that should result in an external force strong enough to create change, often it doesn’t and we try more of what didn’t work, but try it harder. Though the scenarios are different, in both the external force is insufficient to create new behavior.

In order to know which camp you’re in, it’s important to know how we decide between what worked and what didn’t (or between working and not working). To decide, we compare outcomes to expectations, and if outcomes are more favorable than our expectations, it worked; if less favorable, it didn’t. It’s strange, but true – what we expect delineates what worked from what didn’t and what’s good enough from what isn’t. In that way, it’s our choice.

Whether our business model is working, isn’t working, or hasn’t worked, what we think and do about it is our choice. What that means is, regardless of the magnitude of the external force, we decide if it’s large enough to do our work differently or do different work. And because innovation starts with different, what that means is innovation is a choice – our choice.

Really, though, external forces don’t create new behavior, internal forces do. We watch the culture around us and sense the external forces it creates on us, then we look inside and choose to apply the real force behind innovation – our intrinsic motivation. If we’re motivated by holding on to what we have, we’ll spend little of our life force on innovation. If we’re motivated by a healthy dissatisfaction with the status quo, we’ll empty our tank in the name of innovation.

Who is tasked with innovation at your company is an important choice, because while the tools and methods of innovation can be taught, a person’s intrinsic motivation, a fundamental forcing function of innovation, cannot.

Image credit – Ed Yourdon

The Best Leading Indicator of Innovation

Evaluation of innovation efforts is a hot topic. Sometimes it seems evaluating innovation is more important than innovation itself.

Evaluation of innovation efforts is a hot topic. Sometimes it seems evaluating innovation is more important than innovation itself.

Metrics, indicators, best practices, success stories – everyone is looking for the magical baseline data to compare to in order to define shortcomings and close them. But it’s largely a waste of time, because with innovation, it’s different every time. Look back two years – today’s technology is different, the market is different, and the people are different. If you look back and evaluate what went on and then use that learning to extrapolate what will happen in the future, well, that’s like driving a Formula One car around the track while looking in the rear view mirror. You will crash and you will get hurt because, by definition, with innovation, what you did in the past no longer applies, even to you.

Here’s a rule – when you look backward to steer your innovation work, you crash.

When you compare yourself to someone else’s innovation rearward looking innovation metrics, it’s worse. Their market was different than yours is, their company culture was different than yours is, their company mission and values were different. Their situation no longer applies to them and it’s less applicable to you, yet that’s what you’re doing when you compare yourself to a rearview mirror look at a best practice company. Crazy.

We’re fascinated with innovation metrics that are easy to measure, but we shouldn’t be. Anything that’s easy to measure cannot capture the nuance of innovation. For example, the number of innovation projects you ran over the last two years is meaningless. What’s meaningful is the incremental profit generated by the novel deliverables of the work and your level of happiness with the incremental profit. Number of issued patents is also meaningless. What’s meaningful is the incremental profit created by the novel goodness of the patented technology and your level of happiness with it. Number of people that worked on innovation projects or the money spent – meaningless. Meaningful – incremental profit generated by the novel elements of the work divided by the people (or cost) that created the novel elements and your level of happiness with it.

Things are a bit better with forward looking metrics – or leading indicators – but not much. Again, our fascination with things that are easy to measure kicks us in the shins. Number of patent applications, number of people working on projects, number of fully staffed technology projects, monthly spend on R&D – all of these are easily measured but are poor predictors innovation results. What if the patented technology is not valued by the customer? What if the people working on projects are working on projects that result in products that don’t sell? What if the fully staffed projects create new technologies for new markets that never come to be? What if your monthly spend is spent on projects that miss the mark?

To me, the only meaningful leading indicator for innovation is a deep understanding of your active technology projects. What must the technology do so the new market will buy it? How do you know that? Can you quantify that goodness in a quantifiable way? Will you know when that goodness has been achieved? In what region will the product be sold? What is the cost target, profit margin and the new customers’ ability to pay? What are the results of the small experiments where the team tested the non-functional prototypes and their price points in the new market? What does the curve look like for price point versus sales volume? What is your level of happiness with all this?

We have an unhealthy fascination with innovation metrics that are easy to measure. Instead of a sea of metrics that are easy to measure, we need nuanced leading indicators that are meaningful. And I cannot give you a list of meaningful leading indicators, because each company has a unique list which is defined by its growth objectives, company culture and values, business models, and competition. And I cannot give you threshold limits for any of them because only you can define that. The leading indicators and their threshold values are context-specific – only you can choose them and only you can judge what levels make you happy. Innovation is difficult because it demands judgment, and no metrics or leading indicators can take judgment out of the equation.

Creativity creates things that are novel and useful while innovation creates things that are novel, useful and successful. Dig into the details of your active technology projects and understand them from a customer-market perspective, because success comes only when customers buy your new products.

Image credit – coloneljohnbritt

Innovation Fortune Cookies

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long.

Whether you like it or not, when you start something new uncertainty carries the day.

Don’t define the idealized future state, advance the current state along its lines of evolutionary potential.

Try new things then do more of what worked and less of what didn’t.

Without starting, you never start. Starting is the most important part

Perfection is the enemy of progress, so are experts.

Disruption is the domain of the ignorant and the scared.

Innovation is 90% people and the other half technology.

The best training solves a tough problem with new tools and processes, and the training comes along for the ride.

The only thing slower than going too slowly is going too quickly.

An innovation best practice – have no best practices.

Decisions are always made with judgment, even the good ones.

image credit – Gwen Harlow

Top Innovation Blogger of 2014

Innovation Excellence announced their top innovation bloggers of 2014, and, well, I topped the list!

Innovation Excellence announced their top innovation bloggers of 2014, and, well, I topped the list!

The list is full of talented, innovative thinkers, and I’m proud to be part of such a wonderful group. I’ve read many of their posts and learned a lot. My special congratulations and thanks to: Jeffrey Baumgartner, Ralph Ohr, Paul Hobcraft, Gijs van Wulfen, and Tim Kastelle.

Honors and accolades are good, and should be celebrated. As Rick Hanson knows (Hardwiring Happiness) positive experiences are far less sticky than negative ones, and to be converted into neural structure must be actively savored. Today I celebrate.

Writing a blog post every week is challenge, but it’s worth it. Each week I get to stare at a blank screen and create something from nothing, and each week I’m reminded that it’s difficult. But more importantly I’m reminded that the most important thing is to try. Each week I demonstrate to myself that I can push through my self-generated resistance. Some posts are better than others, but that’s not the point. The point is it’s important to put myself out there.

With innovative work, there are a lot of highs and lows. Celebrating and savoring the highs is important, as long as I remember the lows will come, and though there’s a lot of uncertainty in innovation, I’m certain the lows will find me. And when that happens I want to be ready – ready to let go of the things that don’t go as expected. I expect thinks will go differently than I expect, and that seems to work pretty well.

I think with innovation, the middle way is best – not too high, not too low. But I’m not talking about moderating the goodness of my experiments; I’m talking about moderating my response to them. When things go better than my expectations, I actively hold onto my good feelings until they wane on their own. When things go poorly relative to my expectations, I feel sad for a bit, then let it go. Funny thing is – it’s all relative to my expectations.

I did not expect to be the number one innovation blogger, but that’s how it went. (And I’m thankful.) I don’t expect to be at the top of the list next year, but we’ll see how it goes.

For next year my expectations are to write every week and put my best into every post. We’ll see how it goes.

Innovation Through Preparation

Innovation is about new; innovation is about different; innovation is about “never been done before”; and innovation is about preparation.

Innovation is about new; innovation is about different; innovation is about “never been done before”; and innovation is about preparation.

Though preparation seems to contradict the free-thinking nature of innovation, it doesn’t. In fact, where brainstorming diverts attention, the right innovation preparation focuses it; where brainstorming seeks more ideas, preparation seeks fewer and more creative ones; where brainstorming does not constrain, effective innovation preparation does exactly that.

Ideas are the sexy part of innovation; commercialization is the profitable part; and preparation is the most important part. Before developing creative, novel ideas, there must be a customer of those ideas, someone that, once created, will run with them. The tell-tale sign of the true customer is they have a problem if the innovation (commercialization) doesn’t happen. Usually, their problem is they won’t make their growth goals or won’t get their bonus without the innovation work. From a preparation standpoint, the first step is to define the customer of the yet-to-be created disruptive concepts.

The most effective way I know to create novel concepts is the IBE (Innovation Burst Event), where a small team gets together for a day to solve some focused design challenges and create novel design concepts. But before that can happen, the innovation preparation work must happen. This work is done in the Focus phase. The questions and discussion below defines the preparation work for a successful IBE.

1. Why is it so important to do this innovation work?

What defines the need for the innovation work? The answer tells the IBE team why they’re in the room and why their work is important. Usually, the “why” is a growth goal at the business unit level or projects in the strategic plan that are missing the necessary sizzle. If you can’t come up with a slide or two with growth goals or new projects, the need for innovation is only emotional. If you have the slides, these will be used to kick off the IBE.

2. Who is the customer of the novel concepts?

Who will choose which concepts will be converted into working prototypes? Who will convert the prototypes into new products? Who will launch the new products? Who has the authority to allocate the necessary resources? These questions define the customers of the new concepts. Once defined, the customers become part of the IBE team. The customers kick off the IBE and explain why the innovation work is important and what they’ll do with the concepts once created. The customers must attend the IBE report-out and decide which concepts they’ll convert to working prototypes and patents.

Now, so the IBE will generate the right concepts, the more detailed preparation work can begin. This work is led by marketing. Here are the questions to scope and guide the IBE.

3. How will the innovative new product be used?

How will the innovative product be used in new way? This question is best answered with a hand sketch of the customer using the new product in a new way, but a short written description (30 words, or so) will do in a pinch. The answer gives the IBE team a good understanding, from a customer perspective, what new things the product must do.

What are the new elements of the design that enable the new functionality or performance? The answer focuses the IBE on the new design elements needed to make real the new product function in the new way.

What are the valuable customer outcomes (VCOs) enabled by the innovative new product? The answer grounds the IBE team in the fundamental reason why the customer will buy the new product. Again, this is answered from the customer perspective.

4. How will the new innovative new product be marketed and sold?

What is the tag line for the new product? The answer defines, at the highest level, what the new product is all about. This shapes the mindset of the IBE team and points them in the right direction.

What is the major benefit of the new product? The answer to this question defines what your marketing says in their marketing/sales literature. When the IBE team knows this, you can be sure the new concepts support the marketing language.

5. By whom will the innovative new product be used?

In which geography does the end user live? There’s a big difference between developed markets and developing markets. The answer to the question sets the context for the new concepts, specifically around infrastructure constraints.

What is their ability to pay? Pocketbooks are different across the globe, and the customer’s ability to pay guides the IBE team toward concepts that fit the right pocket book.

What is the literacy level of the end customer? If the customer can read, the IBE team creates concepts that take advantage of that ability. If the customer cannot read, the IBE team creates concepts that are far different.

6. How will the innovative new product change the competitive landscape?

Who will be angry when the new product hits the market? The answer defines the competition. It gives broad context for the IBE team and builds emotional energy around displacing adversaries.

Why will they be angry? With the answer to this one, the IBE team has good perspective on the flavor of pain and displeasure created by the concepts. Again, it shapes the perspective of the IBE team. And, it educates the marketing/sales work needed to address competitors’ countermeasures.

Who will benefit when the new product hits the market? This defines new partners and supporters that can be part of the new solutions or participants in a new business model or sales process.

What will customer throw away, reuse, or recycle? This question defines the level of disruption. If the new products cause your existing customers to throw away the products of your existing customers, it’s a pure market share play. The level of disruption is low and the level of disruption of the concepts should also be low. On the other end of the spectrum, if the new products are sold to new customers who won’t throw anything away, you creating a whole new market, which is the ultimate disruption, and the concepts must be highly disruptive. Either way, the IBE team’s perspective is aligned with the level appropriate level of disruption, and so are the new concepts.

Answering all these questions before the creative works seems like a lot of front-loaded preparation work, and it is. But, it’s also the most important thing you can do to make sure the concept work, technology work, patent work, and commercialization work gives your customers what they need and delivers on your company’s growth objectives.

Image credit — ccdoh1.

To improve innovation, improve clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

If I was CEO of a company that wanted to do innovation, the one thing I’d strive for is clarity.

For clarity on the innovative new product, here’s what the CEO needs.

Valuable Customer Outcomes – how the new product will be used. This is done with a one page, hand sketched document that shows the user using the new product in the new way. The tool of choice is a fat black permanent marker on an 81/2 x 11 sheet of paper in landscape orientation. The fat marker prohibits all but essential details and promotes clarity. The new features/functions/finish are sketched with a fat red marker. If it’s red, it’s new; and if you can’t sketch it, you don’t have it. That’s clarity.

The new value proposition – how the product will be sold. The marketing leader creates a one page sales sheet. If it can’t be sold with one page, there’s nothing worth selling. And if it can’t be drawn, there’s nothing there.

Customer classification – who will buy and use the new product. Using a two column table on a single page, these are their attributes to define: Where the customer calls home; their ability to pay; minimum performance threshold; infrastructure gaps; literacy/capability; sustainability concerns; regulatory concerns; culture/tastes.

Market classification – how will it fit in the market. Using a four column table on a single page, define: At Whose Expense (AWE) your success will come; why they’ll be angry; what the customer will throw way, recycle or replace; market classification – market share, grow the market, disrupt a market, create a new market.

For clarity on the creative work, here’s what the CEO needs: For each novel concept generated by the Innovation Burst Event (IBE), a single PowerPoint slide with a picture of its thinking prototype and a word description (limited to 12 words).

For clarity on the problems to be solved the CEO needs a one page, image-based definition of the problem, where the problem is shown to occur between only two elements, where the problem’s spacial location is defined, along with when the problem occurs.

For clarity on the viability of the new technology, the CEO needs to see performance data for the functional prototypes, with each performance parameter expressed as a bar graph on a single page along with a hyperlink to the robustness surrogate (test rig), test protocol, and images of the tested hardware.

For clarity on commercialization, the CEO should see the project in three phases – a front, a middle, and end. The front is defined by a one page project timeline, one page sales sheet, and one page sales goals. The middle is defined by performance data (bar graphs) for the alpha units which are hyperlinked to test protocols and tested hardware. For the end it’s the same as the middle, except for beta units, and includes process capability data and capacity readiness.

It’s not easy to put things on one page, but when it’s done well clarity skyrockets. And with improved clarity the right concepts are created, the right problems are solved, the right data is generated, and the right new product is launched.

And when clarity extends all the way to the CEO, resources are aligned, organizational confusion dissipates, and all elements of innovation work happen more smoothly.

Image credit – Kristina Alexanderson

Mind-Body Motivation for Innovation

Mind and body are connected, literally. It’s true – our necks bridge the gap. Don’t believe me? Locate one end of your neck and you’ll find your head or body; locate the other and you’ll find the other. And not only are they connected, they interact. Shared blood flows between the two and that means shared blood chemistry and shared oxygen. And not only is the plumbing shared, so is the electrical. The neck is the conduit for the nerves which pass information between the two and each communicate is done in a closed loop way. Because it’s so obvious, it sounds silly to describe the connectedness in this way, yet we still think of them as separate.

Mind and body are connected, literally. It’s true – our necks bridge the gap. Don’t believe me? Locate one end of your neck and you’ll find your head or body; locate the other and you’ll find the other. And not only are they connected, they interact. Shared blood flows between the two and that means shared blood chemistry and shared oxygen. And not only is the plumbing shared, so is the electrical. The neck is the conduit for the nerves which pass information between the two and each communicate is done in a closed loop way. Because it’s so obvious, it sounds silly to describe the connectedness in this way, yet we still think of them as separate.

When the mind-body is combined into a single element our perspectives change. For one, we realize the significance of the environment because wherever the body is the mind is. If your body walks your mind to a hot place, your body is hot and so is your mind. No big deal? Go to the beach in mid- summer, stand in the 105 degree heat for 1 hour, then do some heavy critical thinking. Whether the environment is emotionally hot or temperature hot, it won’t go well. Sit your body in a noisy, chaotic environment for two hours then try to come up with the new technology to keep your company solvent. Keep your body awake for 24 hours and try to solve a fundamental problem to reinvent your business model. I don’t think so.

Innovation is like a marathon, and if you treat your body like a marathon runner you’ll be in great shape to innovate. Get regular physical activity; eat well; get enough sleep; don’t go out and party every night; drink your fluids; don’t get over heated. If you don’t think any of this matters, do the opposite for a week or two and see how it goes with your innovation. And as with innovation climate, geography and environment matter. Train at altitude and sleep in a hypobaric chamber and your mind-body responds differently. Run up hill and you get faster on the hills and likely slower on the flats. Run downhill and your legs hurt. Run in sub-zero temperatures and your lungs burn.

Just as the mind goes with the body, the body follows mind. If you are anxious about your work, you feel a cold pressure in your chest – a clear example where your mental state influences your body. If you are depressed, your body can ache – another example where your mind changes your body. But it’s more than unpleasant body sensations. Your body does far more than move your head place-to-place. Your body is the antenna for the unsaid, and the unsaid is huge part of innovation. Imagine a presentation to your CEO where you describe your one year innovation project that came up empty. When you stop talking and there’s a minute of silent unsaid-ness, your body picks up the signals, not your mind. (You feel the tightness in your chest before you know why.) But if your mind has been monkeying with your body, your crumpled antenna may receive incorrect signals or may transmit them to your brain improperly, and when the CEO asks the hard question, your mind-body is spongy.

And what fuels the mind-body? Why does it get out of bed? Why does it want to do innovation? Dan Pink has it right – when it comes to tasks with high cognitive load, the mind-body is powered by autonomy, the pursuit of mastery, and purpose. For innovation, the mind-body is powered intrinsically, not extrinsically. If your engineers aren’t innovating, it’s because their mind-bodies know there’s no autonomy in the ether. If they’re not taking on the impossible, it’s because they aren’t given time to master its subject matter or the work they’re given is remedial. If they’re doing what they always did, it’s because their antennas aren’t resonating with the purpose behind the innovation work.

When your innovation work isn’t what you’d like it’s not a people problem, it’s an intrinsic motivation problem. Innovators’ mind-bodies desperately want to pole vault out of bed and innovate like nobody’s business, but they feel they have too little control over what they do and how they do it; they want to put all their life force into innovation, but they know (based on where their mind-bodies are) they’re not given the tools, time, and training to master their craft; and the rationale you’ve given them – the “WHY” in why they should innovate – is not meaningful to their mind-bodies.

Innovation is a full mind-body sport, and the importance of the body should be elevated. And if there’s one thing to focus on it’s the innovation environment in which the mind-body sits.

Innovators were born to innovate – our mind-bodies don’t have a choice. And if innovation is not happening it’s because extrinsic motivation strategies (carrots and sticks) are blocking the natural power of our intrinsic motivation. It’s time to figure that one out.

Image credit – Eli Duke

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski