Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

Companies, Acquisitions, Startups, and Hurricanes

If you run a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. You can’t control how the people in your company will respond to input, but you can choose the projects they work on. You can’t control which features and functions your customers will like, but you can choose which features and functions become part of the next product. And you can’t control if a new technology will work, but you can choose the design space to investigate. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to buy a company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. In this case, the resources are your hard-earned money and your choice is which company to buy. The open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

If you want to invest in a startup company, the most important thing you can control is how you allocate your resources. This case is the same as the previous one – your money is the resource and the company you choose defines how you allocate your resources. This one is a little different in that the uncertainty is greater, but so is the potential reward. Again, the same open question – How to choose in a way that increases your probability of success?

Taking a step back, the three scenarios can be generalized into a category called a “system.” And the question becomes – how to understand the system in a way that improves resource allocation and increases your probability of success?

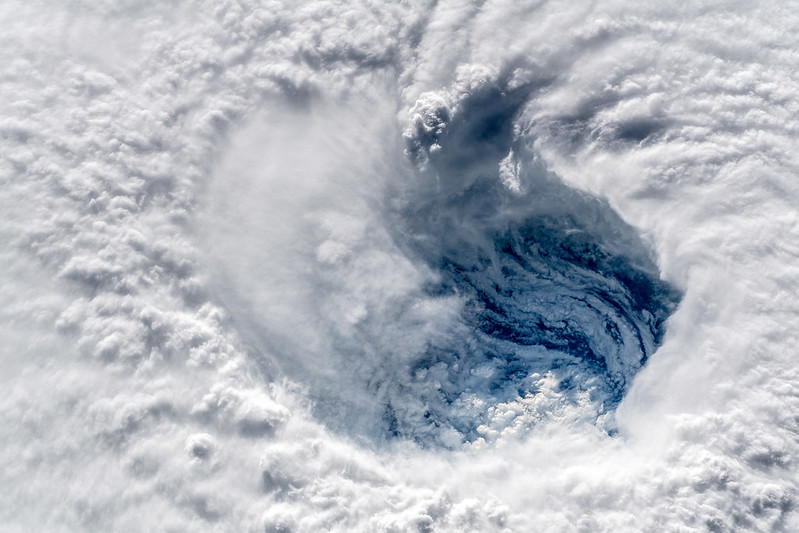

These people systems aren’t predictable in an if-A-then-B way. But they do have personalities or dispositions. They’ve got characteristics similar to hurricanes. A hurricane’s exact path cannot be forecasted, the meteorologist can use history and environmental conditions to broadly define regions where the probability of danger is higher. The meteorologist continually monitors the current state of the hurricane (the system as it is) and tracks its position over time to get an idea of its trajectory (a system’s momentum). The key to understanding where the hurricane could go next: where it is right now (current state), how it got there (how it has behaved over time), and how have other hurricanes tracked under similar conditions (its disposition). And it’s the same for systems.

To improve your understanding of how your system may respond, understand it as it is. Define the elements and how those elements interact. Then, work backward in time to understand previous generations of the system. Which elements were improved? Which ones were added? Then, like the meteorologist, start at the system’s genesis and move forward to the present to understand its path. Use the knowledge of its path and the knowledge of systems (it’s important to be the one that improves the immature elements of the system and systems follow S-curves until the S-curve flattens) to broadly define regions where the probability of success is higher.

These methods won’t guarantee success. But, they will help you choose projects, choose acquisitions, choose technologies, and choose startups in a way that increases your probability of success.

Image credit — Alexander Gerst

When Best Practice Withers Into Old Practice

When best practices get old, they turn into ruts of old practice. No, it doesn’t make sense to keep doing it this way, but we’ve done it this way in the past, we’ve been successful, and we’re going to do it like we did last time. You can misuse old practices long after they’ve withered into decrepit practices, but, ultimately, your best practices will turn into old practices and run out of gas. And then what?

It’s unskillful to wait until the wheels fall off before demonstrating a new practice – a new practice is a practice that you’ve not done before – but that’s what we mostly do. There’s immense pressure to do what we did last time because we know how it turned out last time. But when the environment around a process changes, there’s no guarantee that the output of the old process will adequately address the changing environment. What worked last time will work next time, until it doesn’t.

But there’s another reason why we don’t try new practices. We’ve never taught people how to do it. Here are some thoughts on how to try new practices.

- If you think the work can be done a better way, try a new practice, then decide if it was better. If the new practice was better, do it that way until you come up with an even better practice. Rinse and repeat.

- Don’t ask, just try the new practice.

- When you try a new practice, do it in a way that is safe to fail. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for that language.) Like before you use a new cleaning product to remove a stain on your best sweater, test the new practice in a way that won’t ruin your sweater.

- If someone asks you to use the old practice instead of trying the new practice, ask them to do it the old way and you do it the new way.

- If that someone is your boss, tell them you’re happy to do WHAT they want but you want to be the one that decides HOW to do it.

- If your boss still wants you to follow the old practice, do it the old way, do it the new way, and look for a new job because your boss isn’t worth working for.

Just because best practices were best last time, doesn’t mean they’re good practice this time.

Image credit – Dustin Moore

How To Know if You’re Moving in a New Direction

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

When it’s time to change course, I have found that companies error on the side of arguing what to call it and how to go about it. Sure, this comes at the expense of doing it, but that’s the point. At the surface, it seems like there’s a need for the focus groups and investigatory dialog because no one knows what to do. But it’s not that the company doesn’t know what it must do. It’s that no one is willing to make the difficult decision and own the consequences of making it.

Once the decision is made to change course and the new direction is properly named, the talk may have stopped but the new work hasn’t started. And this is when it’s time to create an objective measure to help the company discern between talking about the course change and actively changing the course.

Here it is in a nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects change.

Here’s the failure mode to guard against. When the naming conventions in the operating plans reflect the new course heading but sitting under the flashy new moniker is the same set of tired, old projects. The job of the objective measure is to discern between the same old projects and new projects that are truly aligned with the new direction.

And here’s the other half of the nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects solve different problems.

To discern if the company is working in a new direction, the objective measure is a one-page description of the new customer problem each project will solve. The one-page limit helps the team distill their work into a singular customer problem and brings clarity to all. And framing the problem in the customer’s context helps the team know the project will bring new value to the customer. Once the problem is distilled, everyone will know if the project will solve the same old problem or a new one that’s aligned with the company’s new course heading. This is especially helpful the company leaders who are on the hook to move the company in the new direction. And ask the team to name the customer. That way everyone will know if you are targeting the same old customer or new ones.

When you have a one-page description of the problem to be solved for each project in your portfolio, it will be clear if your company is working in a new direction. There’s simply no escape from this objective measure.

Of course, the next problem is to discern if the resources have actually moved off the old projects and are actively working on the new projects. Because if the resources don’t move to the new projects, you’re not solving new problems and you’re not moving in the new direction.

Image credit – Walt Stoneburner

Disruption – the work that makes the best things obsolete.

I think the word “disruption” doesn’t help us do the right work. Instead, I use “innovation.” But that word has also lost much of its usefulness. There are different flavors of innovation and the flavor that maps to disruption is the flavor that makes things obsolete. This flavor of new work doesn’t improve things, it displaces them. So, when you see “innovation” in my posts, think “work that makes the best things obsolete.”

Doing work that makes the best things obsolete requires new behavior. Here’s a post that gives some tips to help make it easy for new behaviors to come to be. Within the blog post, there is a link to a short podcast that’s worth a listen. One Good Way to Change Behavior

And here’s a follow-on post about what gets in the way of new behavior. What’s in the way?

It’s difficult to define “disruption.” Instead of explaining what disruption is or isn’t, I like to use “no-to-yes.” Don’t improve the system by 3%, instead use no-to-yes to make the improved system do something the existing system cannot. Battle Success With No-to-Yes

Instead of “disruption” I like “compete with no one.” To compete with no one, you’ve got to make your services so fundamentally good that your competition doesn’t stand a chance. Compete With No One

Disruption, as a word, is not actionable. But here’s what is actionable: Choose to solve new problems. Choose to solve problems that will make today’s processes and outcomes worthless. Before you solve a problem ask yourself “Will the solution displace what we have today?” Innovation In Three Words

Here’s a nice operational definition of how to do disruption – Obsolete your best work.

And if you’re not yet out of gas, here are some posts that describe what gets in the way of new behavior and how to create the right causes and conditions for new behaviors to emerge.

Creating the Causes and Conditions for New Behavior to Grow

The only thing predictable about innovation is its unpredictability.

For innovation to flow, drive out fear.

Image credit — Thomas Wensing

Speed Through Better Decision Making

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

If you want to go faster there are three things to focus on: decisions, decisions, and decisions.

First things first – define the decision criteria before the work starts. That’s right – before. This is unnatural and difficult because decision criteria are typically poorly defined, if not undefined, even when the work is almost complete. Don’t believe me? Try to find the agreed-upon decision criteria for an active project. If you can find them, they’ll be ambiguous and incomplete. If you can’t find them, well, there you go.

Decision criteria aren’t just categories -like sales revenue, speed, weight – they all must have a go-no-go threshold. Sales must be greater than X, speed must be greater than Y and weight must be less than Z. A decision criterion is a category with a threshold value.

Second, before the work starts, define the actions you’ll take if the threshold values are achieved and if they are not. If sales are greater than X, speed is greater than Y and weight is less than Z, we’ll invest A dollars a year for B years to scale the business. If one of X, Y or Z are less than their threshold value, we’ll scrap the project and distribute the team throughout the organization.

Lastly, before the work starts, define the decision-maker and how their decision will be documented and communicated. In practice, there is usually just one decision-maker. So, strive to write down just one person’s name as the decision-maker. But that person will be reluctant to sign up as the decision-maker because they don’t want to be mapped the decision if things flop. Instead, the real decision-maker will put together a committee to make the decision.

To tighten things down for the committee, define how the decision will be made. Will it be a simple majority vote, a supermajority, unanimous decision or the purposefully ambiguous consensus vote. My bet is on consensus, which allows the individual committee members to distance themselves from the decision if it goes badly. And, it allows the real decision-maker to influence the consensus and effectively make the decision without making it.

Formalizing the decision process creates speed. The decision categories help the team avoid the wrong work and the threshold values eliminate the time-wasting is-it-good-enough arguments. When the follow-on actions are predefined, there’s no waiting there’s just action. And defining upfront the decision-maker and the mechanism eliminates the time-sucking ambiguity that delays decisions.

Don’t change culture. Change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

There’s always lots of talk about culture and how to change it. There is culture dial to turn or culture level to pull. Culture isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a sentiment that’s generated by behavioral themes. Culture is what we use to describe our worn paths of behavior. If you want to change culture, change behavior.

At the highest level, you can make the biggest cultural change when you change how you spend your resources. Want to change culture? Say yes to projects that are different than last year’s and say no to the ones that rehash old themes. And to provide guidance on how to choose those new projects create, formalize new ways you want to deliver new value to new customers. When you change the criteria people use to choose projects you change the projects. And when you change the projects people’s behaviors change. And when behavior changes, culture changes.

The other important class of resources is people. When you change who runs the project, they change what work is done. And when they prioritize a different task, they prioritize different behavior of the teams. They ask for new work and get new behavior. And when those project leaders get to choose new people to do the work, they choose in a way that changes how the work is done. New project leaders change the high-level behaviors of the project and the people doing the work change the day-to-day behavior within the projects.

Change how projects are chosen and culture changes. Change who runs the projects and culture changes. Change who does the project work and culture changes.

Image credit – Eric Sonstroem

Wanting things to be different

Wanting things to be different is a good start, but it’s not enough. To create conditions for things to move in a new direction, you’ve got to change your behavior. But with systems that involve people, this is not a straightforward process.

To create conditions for the system to change, you must understand the system”s disposition – the lines along which it prefers to change.. And to do that, you’ve got to push on the system and watch its response. With people systems, the response is not knowable before the experiment.

If you expect to be able to predict how the system will respond, working with people systems can be frustrating. I offer some guidance here. With this work, you are not responsible for the system’s response, you are only responsible for how you respond to the system’s response.

If the system responds in a way you like, turn that experiment into a project to amplify the change. If the system responds in a way you dislike, unwind the experiment. Here’s a simple mantra – do more of what works and less of what doesn’t. (Thanks to Dave Snowden for this.)

If you don’t like how things are going, you have only one lever to pull. You can only change.your response to what you see and experience. You can respond by pushing on the system and responding to what you see or you can respond by changing what you think and feel about the system.

But keep in mind that you are part of the system. And maybe the system is running an experiment on you. Either way, your only choice is to choose how to respond.

Before solving, learn more about the problem.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Ideas are cheap, but converting them into a saleable product and building the engine to make it all happen is expensive. Before spending the big money, spend more time than you think reasonable to answer these three questions.

Is the problem big enough? There’s no sense spending the time and money to solve a problem unless you have a good idea the payback is worth the cost. Before spending the money to create the solution, spend the time to assess the benefits that will come from solving the problem.

Before you can decide if the problem is big enough, you have to define the problem and know who has it. One of the best ways to do this is to define how things are done today. Draw a block diagram that defines the steps potential customers follow or draw a picture of how they do things today. Define the products/services they use today and ask them what it would mean if you solved their problem. What’s particularly difficult at this point is they may not know they have a problem.

But before moving on, formalize who has the problem. Define the attributes of the potential customers and figure out how many have the same attributes and, possibly, the same problem. Define the segments narrowly to make sure each segment does, in fact, have the same problem. There will be a tendency to paint with broad strokes to increase the addressable market, but stay narrow and maintain focus on a tight group of potential customers.

Estimate the value of the solution based on how it compares to the existing alternative. And the only ones who can give you this information are the potential customers. And the only way they can give you the information is if you interview them and watch them work. And with this detailed knowledge, figure out the number of potential customers who have the problem. Do all this BEFORE any solving.

Will they pay for it? The only way to know if potential customers will pay for your solution is to show them an offering – a description of your value proposition and how it differs from the existing alternatives, a demo (a mockup of a solution and not a functional prototype) and pricing. (See LEANSTACK for more on an offering.) There will be a tendency to wait until the solution is ready, but don’t wait. And there will be a reluctance attach a price to the solution, but that’s the only way you’ll know how much they value your solution. And there will be difficulty defining a tight value proposition because that requires you to narrowly define what the solution does for the potential customer. And that’s scary because the value proposition will be clear and understandable and the potential customer will understand it well enough to decide they if they like it or not.

If you don’t assign a price and ask them to buy it, you’ll never know if they’ll buy it in real life.

Can you deliver it? List all the elements that must come together. Can you make it? Can you sell it? Can you ship it? Can you service it? Are your partners capable and committed? Do you have the money do put everything in place?

Like with a chain, it takes one bad link to make the whole thing fall apart. Figure out if any of your links are broken or missing. And don’t commit resources until they’re all in place and ready to go.

Image credit — Matthias Ripp

As a leader, your response is your responsibility.

When you’re asked to do more work that you and your team can handle, don’t pass it onto your team. Instead, take the heat from above but limit the team’s work to a reasonable level.

When you’re asked to do more work that you and your team can handle, don’t pass it onto your team. Instead, take the heat from above but limit the team’s work to a reasonable level.

When the number of projects is larger than the budget needed to get them done, limit the projects based on the budget.

When the team knows you’re wrong, tell them they’re right. And apologize.

When everyone knows there’s a big problem and you’re the only one that can fix it, fix the big problem.

When the team’s opinion is different than yours, respect the team’s opinion.

When you make a mistake, own it.

When you’re told to do turn-the-crank work and only turn-the-crank work, sneak in a little sizzle to keep your team excited and engaged.

When it’s suggested that your team must do another project while they are fully engaged in an active project, create a big problem with the active project to delay the other project.

When the project is going poorly, be forthcoming with the team.

When you fail to do what you say, apologize. Then, do what you said you’d do.

When you make a mistake in judgement which creates a big problem, explain your mistake to the team and ask them for help.

If you’ve got to clean up a mess, tell your team you need their help to clean up the mess.

When there’s a difficult message to deliver, deliver it face-to-face and in private.

When your team challenges your thinking, thank them.

When your team tells you the project will take longer than you want, believe them.

When the team asks for guidance, give them what you can and when you don’t know, tell them.

As leaders, we don’t always get things right. And that’s okay because mistakes are a normal part of our work. And projects don’t always go as planned, but that’s okay because that’s what projects do. And we don’t always have the answers, but that’s okay because we’re not supposed to. But we are responsible for our response to these situations.

When mistakes happen, good leaders own them. When there’s too much work and too little time, good leaders tell it like it is and put together a realistic plan. And when the answers aren’t known, a good leader admits they don’t know and leads the effort to figure it out.

None of us get it right 100% of the time. But what we must get right is our response to difficult situations. As leaders, our responses should be based on honesty, integrity, respect for the reality of the situation and respect for people doing the work.

Image credit – Ludovic Tristan

Subtle Leadership

You could be a subtle leader if…

You could be a subtle leader if…

You create the causes and conditions for others to shine. And when they shine, you give them the credit they’re due.

You don’t have the title, but when the high-profile project hits a rough patch, you get called in to create the go-forward plan.

One of your best direct reports gets promoted out from under you, but she still wants to meet with you weekly.

When you see someone take initiative, you tell them you like their behavior.

You get to choose the things you work on.

You can ask most anyone for a favor and they’ll do it, just because it’s you. But, because you don’t like to put people out, you rarely ask.

When someone does a good job, you send their boss a nice email and cc: them.

When it’s time to make a big decision, even though it’s outside your formal jurisdiction, you have a seat at the table.

When people don’t want to hear the truth, they don’t invite you to the meeting.

You are given the time to think things through, even when it takes you a long time.

Your young boss trusts you enough to ask for advice, even when she knows she should know.

In a group discussion, you wait for everyone else to have input before weighing in. And, if there’s no need to weigh in, you don’t.

When you see someone make a mistake, you ignore it if you can. And if you can’t, you talk to them in private.

Subtle leaders show themselves in subtle ways but their ways are powerful. Often, you see only the results of their behaviors and those career-boosting results are mapped to someone else. But if you’ve been the recipient of subtle leadership, you know what I’m talking about. You didn’t know you needed help, but you were helped just the same. And you were helped in a way that was invisible to others. And though you didn’t know to ask for advice, you were given the right suggestion at the right time. And you didn’t realize it was the perfect piece of advice until three weeks later.

Subtle leaders are difficult to spot. But once you know how they go about their business and how the company treats them, you can see them for what they are. And once you recognize a subtle leader, figure out a way to spend time with them. Your career will be better for it.

Image credit – rawdonfox

Productivity Through Prioritization

If you haven’t noticed, the pace and complexity of our work is ever-increasing. There’s more to do and there are more interactions among the players and the tasks. And though there’s more need for thinking and planning, there’s less time to do it. And the answer from company leadership – more productivity.

If you haven’t noticed, the pace and complexity of our work is ever-increasing. There’s more to do and there are more interactions among the players and the tasks. And though there’s more need for thinking and planning, there’s less time to do it. And the answer from company leadership – more productivity.

With the traditional view of productivity, it’s do more with less. That works for a while and then it doesn’t. And when you can no longer do more, the only remaining way to improve productivity is to do less.

If you try to do all five things and get four done poorly, wouldn’t it be more productive if you tried to do only three things and did them well? None of the three would have to touched up or redone. And none of the three would occupy your emotional bandwidth because they were done well and they’re not coming back to bite you. And because you focused on three things, you spent only three things worth of energy. Your life force is conserved and when you get home you still have gas in the tank.

If you get three things done each day, you’ll accomplish more than anyone else in the company. Don’t think so? Three things per day is fifteen things per week. And if you work fifty weeks per year, three things per day is one hundred and fifty things per year. (I hope you don’t work fifty weeks per year, I chose this number because it makes the math cleaner.)

It’s not easy to get three things done per day. With meetings, email, texts and the various collaboration platforms, you have almost zero uninterrupted time. And with zero uninterrupted time, you get about zero things done. And if I have to choose between getting three things done or zero things done, I choose three. It’s difficult to allocate the time to get three things done, but it’s possible.

Three things may not seem like enough things, but three is enough. Here’s why. You don’t do just any three things, you do three important things. You choose what you want to get done and you get them done. The key is to decide which three things you’ll get done and which three hundred you won’t. To do this, take some time at the end of the day to define tomorrow’s three things. That way, first thing, you’ll get after the right three things. It’s productivity through prioritization. You’ve got to do fewer things to get more done.

And you can still deliver on large projects with the three-things-per-day method. For large projects, most, if not all, of the day’s three things should be directly related to the project. Remember the math – you can do fifteen things per week on a large project. And it works for long projects, too. Do one thing per week on the long project and you will accomplish fifty things over the course of the year. When was the last time you completed fifty things on a project?

And if you think three things is too few, that’s fine. If you want to do more than three things, you can. Just make sure you know which three you’ll complete before moving on to the fourth. But, remember, you want to leave work with some gas still in the tank so you can do three things when you get home.

Image credit – Steve @ the alligator farm

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski