Archive for the ‘How To’ Category

How To Reduce the Tariff Signature of Your Supply Chain

Supply chains have taken it on the chin, first from COVID-19 and now from tariffs (or the threat of them). For the second time in several years, we have objective evidence there is more to a supply chain than implementing the lowest-cost way to meet predictable demand. Tariffs have highlighted the cost of an inflexible supply chain because we can quantify the savings from moving parts to countries with lower tariffs.

Supply chains have taken it on the chin, first from COVID-19 and now from tariffs (or the threat of them). For the second time in several years, we have objective evidence there is more to a supply chain than implementing the lowest-cost way to meet predictable demand. Tariffs have highlighted the cost of an inflexible supply chain because we can quantify the savings from moving parts to countries with lower tariffs.

With tariffs, Lean’s mantra of “make it where you sell it” has sharper teeth.

At the most fundamental level, supply chains are governed by the parts. Big parts, big factories; small parts, small machines; high part volume, high volume processes; low part volume, low volume processes; specialized coatings on the parts, specialized suppliers; parts with proprietary materials, sole source supplier. The supply chain is defined by its parts. And when you try to move the manufacture of parts from one country to another, these part-based constraints are the very thing that creates supply chain inflexibility. Said another way, if you want to improve a supply chain’s flexibility, you’ve got to start with the parts. If you want to reduce the tariffs of your supply chain, start with the parts.

All the parts in the supply chain are important but with tariffs, some parts are more important than others. You can make significant improvements in your supply chain’s tariff signature if you know the handful of parts that will deliver the largest tariff reduction. For each part within your supply chain calculate

(material cost x volume x tariff percentage)

and sort the product from largest to smallest. For the top ten parts assess the part-specific constraints that governed the original decision of the supplier and country. For each part identify a country with lower tariffs and pair it with the part-specific constraints. You now have a list of the top ten opportunities to reduce the tariff signature, what must change in the design to move to a lower tariff location, and the entitlement savings. The DFM-based tariff savings for each part is

(part cost x volume x difference in tariff percentage).

Take your top ten list to the product owner and show them the potential savings and ask to meet with the design community so you can explain how each part must change so it can move to a lower tariff country. And tell them how much the company will save if those constraints are overcome. This is like classic Design for Manufacturing (DFM) where the part is changed to reduce the cost to make the part, but, instead, the part is changed to reduce the cost of tariffs.

You now have a playbook for the top ten parts, the estimated tariff savings, and the work required to realize those savings. You don’t have to implement the playbook, but you can. And you can repeat the process for the next ten most important parts (11-20). Now you have a playbook for twenty parts and the estimated savings. You can continue the process as needed and step through the list ten parts at a time.

The process I describe is a good way to reduce the cost of tariffs. But to make a dent in the universe, there’s a much better way. It’s called Design For Assembly, or DFA, which is all about product simplification through part elimination. 35% reductions in the number of parts are typical. With DFA, high-tariff parts aren’t changed, they’re eliminated. But where classic DFA prioritizes eliminating the highest-cost parts, tariff-based DFA prioritizes eliminating parts with the highest tariff costs. The calculations to prioritize DFA-based tariff reduction are similar to those for DFM, but the savings are far more severe – the entire tariff and the part cost are saved. The DFA savings are

(part cost x volume x tariff percentage) + (part cost x volume)

Run the calculation for the parts in your supply chain and sort the results from largest to smallest. Take the list of the top ten to the design community and show them how much they can save if they eliminate the parts. Tell them they’ll be the Heros of the Company if they pull it off. Tell them you help them get the tools and training they’ll need. Repeat for the second group of the ten most important parts (11-20).

DFM and DFA are wildly profitable and with the added savings of tariffs, the savings are beyond wild. If there was ever a time to do DFM and DFA, it’s is now.

Image credit — Derell Licht

Ways To Improve Communication

Clarity. People will know why they dislike (or like) your position, have good ideas on improving it, and appreciate your clarity. Well, at least they’ll recognize you’re communicating differently.

Clarity. People will know why they dislike (or like) your position, have good ideas on improving it, and appreciate your clarity. Well, at least they’ll recognize you’re communicating differently.

Brevity. Make it short.

Visual. When you draw a picture of the situation, people will understand the main system elements and how they interact. Use arrows to describe how the system changes over time. Even better, create a series of snapshots in a time series so you can decide to solve the problem before, during, or after. Words constrict. Use images to create space for divergent perspectives.

Distilled. When you converge on the most important theme, the discussion is focused on the most important thing. And when it strays it’s easy to recognize and put it back to importance. To distill, limit yourself to one page and limit the number of words to twelve. This is unnatural and requires confidence through practice.

Know what you want to communicate. Use fewer and simpler words. Decide what to leave out. Use images and cartoons. Make it clean.

Less is more.

Image credit — Charlie Wales

Making a difference starts with recognizing the opportunity to make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference, but if you don’t recognize the need to make one, you won’t make one.

When you’re in a meeting, watch and listen. If someone is quiet, ask them a question. My favorite is “What do you think?” Your question says you value them and their thinking, and that makes a difference. Others will recognize the difference you made, and that may inspire them to make a similar difference at their next meeting.

When you see a friend in the hallway, look them in the eyes, smile, and ask them what they’re up to. Listen to their words but more importantly watch their body language. If you recognize they are energetic, acknowledge their energy, ask what’s fueling them, and listen. Ask more questions to let them know you care. That will make a difference. If you recognize they have low energy, tell them, and then ask what that’s all about. Try to understand what’s going on for them. You don’t have to fix anything to make a difference, you have to invest in the conversation. They’ll recognize your genuine interest and that will make a difference.

If you remember someone is going through something, send them a simple text – “I’m thinking of you.” That’s it. Just say that. They’ll know you remembered their situation and that you care. And that will make a difference. Again, you don’t have to fix anything. You just have to send the text.

Check in with a friend. That will make a difference.

When you learn someone got a promotion, send them a quick note. Sooner is better, but either way, you’ll make a difference.

Ask someone if they need help. Even if they say no, you’ve made a difference. And if they say yes, help them. That will make a big difference.

And here’s a little different spin. If you need help, ask for it. Tell them why you need it and explain why you asked them. You’ll demonstrate vulnerability and they’ll recognize you trust them. Difference made. And your request for help will signal that you think they’re capable and caring. Another difference made.

It doesn’t take much to make a difference. Pay attention and take action and you’ll make a difference. But really, you’ll make two differences. You’ll make a difference for them and you’ll make a difference for yourself.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

The Power of the Reverse Schedule

When planning a project, we usually start with a traditional left-to-right schedule. On the left is the project’s start date, where tasks are added sequentially rightward toward completion. When all the tasks are added and the precedence relationships shift tasks rightward, the completion date becomes known. No one likes the completion date, but it is what it is until we’re asked to pull it in.

When planning a project, we usually start with a traditional left-to-right schedule. On the left is the project’s start date, where tasks are added sequentially rightward toward completion. When all the tasks are added and the precedence relationships shift tasks rightward, the completion date becomes known. No one likes the completion date, but it is what it is until we’re asked to pull it in.

I propose a different approach – a reverse schedule. Instead of left to right, the reverse schedule moves right to left. It starts with the completion date on the right and stacks tasks backward in time toward today. The start date emerges when all the tasks are added and precedence relationships work their magic. Where the traditional schedule tells us when the project will finish, the reverse schedule tells us when we should start. And, usually, the reverse schedule says we should have started several months ago and the project is already late.

There are some subtle benefits of the reverse schedule. It’s difficult to game the schedule and reduce task duration to achieve a desired start date because the tasks are stacked backward in time. (Don’t believe me? Give it a try and you’ll see.) And because the task duration is respectful of the actual work content, the reverse schedule is more realistic. And when there’s too much work in a reverse schedule, the tasks push their way into the past and no one can suggest we should go back in time and start the project three months ago. And since the end date is fixed, we are forced to acknowledge there’s not enough time to do all the work. The beauty of the reverse schedule is it can tell us the project is late BEFORE we start the project.

Here’s a rule: You want to know you’re late before it’s too late.

The real power of the reverse schedule is that it creates a sense of urgency around starting the project. In the project planning phase, a delay of a week here and there is no big deal. But, when the start date slips a day, the completion date slips a day. The reverse schedule clarifies the day-for-day slip and helps the resources move the project sooner so the project can start sooner. And those of us who run projects for a living know this is a big deal. What would you pay for an extra two weeks at the end of a project that’s two weeks behind schedule? Well, if you started two weeks sooner, you wouldn’t need the extra time.

The project doesn’t start when the project schedule says it starts. The project starts when the resources start working on the project in a full-time way. The reverse schedule can create the sense of urgency needed to get the critical resources moved to the project so they can start the work on time.

Image credit — Steve Higgins

It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Tariffs. Economic uncertainty. Geopolitical turmoil. There’s no time for elegance. It’s time for the art of the possible.

Give your sales team a reason to talk to customers. Create something that your salespeople can talk about with customers. A mildly modified product offering, a new bundling of existing products, a brochure for an upcoming new product, a price reduction, a program to keep prices as they are even though tariffs are hitting you. Give them a chance to talk about something new so the customers can buy something (old or new).

Think Least Launchable Unit (LLU). Instead of a platform launch that can take years to develop and commercialize, go the other way. What’s the minimum novelty you can launch? What will take the least work to launch the smallest chunk of new value? Whatever that is, launch it now.

Take a Frankensteinian approach. Frankenstein’s monster was a mix and match of what the good doctor had scattered about his lab. The head was too big, but it was the head he had. And he stitched onto the neck most crudely with the tools he had at his disposal. The head was too big, but no one could argue that the monster didn’t have a head. And, yes, the stitching was ugly, but the head remained firmly attached to the neck. Not many were fans of the monster, but everyone knew he was novel. And he was certainly something a sales team could talk about with customers. How can you combine the head from product A with the body of product B? How can you quickly stitch them together and sell your new monster?

Less-With-Far-Less. You’ve already exhausted the more-with-more design space. And there’s no time for the technical work to add more. It’s time for less. Pull out some functionality and lots of cost. Make your machines do less and reduce the price. Simplify your offering and make things easier for your customers. Removing, eliminating, and simplifying usually comes with little technical risk. Turning things down is far easier than turning them up. You’ll be pleasantly surprised how excited your customers will be when you offer them slightly less functionality for far less money.

These are trying times, but they’re not to be wasted. The pressure we’re all under can open us up to do new work in new ways. Push the envelope. Propose new offerings that are inelegant but take advantage of the new sense of urgency forced.

Be bold and be fast.

Image credit — Geoff Henson

Can you put it on one page?

Anyone can create a presentation with thirty slides, but it takes a rare bird to present for thirty minutes with a single slide.

Anyone can create a presentation with thirty slides, but it takes a rare bird to present for thirty minutes with a single slide.

With thirty slides you can fully describe the system. With one slide you must know what’s important and leave the rest. With thirty slides you can hide your lack of knowledge. With one slide it’s clear to all that you know your stuff, or you don’t.

With one slide you’ve got to know all facets of the topic so you can explain the interactions and subtleties on demand. With thirty slides you can jump to the slide with the answer to the question. That’s one of the main reasons to have thirty slides.

It’s faster to create a presentation with thirty slides than a one-slide presentation. The thirty slides might take ten hours to create, but it takes decades of experience and study to create a one-slide presentation.

If you can create a hand sketch of the concept and explain it for thirty minutes, you will deliver a dissertation. With a one-slide-per-minute presentation, that half hour will be no more than a regurgitation.

Thirty slides are a crutch. One slide is a masterclass.

Thirty slides – diluted. One slide – distilled.

Thirty slides – tortuous. One slide – tight.

Thirty slides – clogged. One slide – clean.

Thirty slides – convoluted. One slide – clear.

Thirty slides – sheet music. One slide – a symphony.

With fewer slides, you get more power points.

With fewer slides, you get more discussion.

With fewer slides, you show your stuff more.

With fewer slides, you get to tell more stories.

With fewer slides, you deliver more understanding.

If you delete half your slides your presentation will be more effective.

If you delete half your slides you’ll stand out.

If you delete half your slides people will remember.

If you delete half your slides the worst outcome is your presentation is shorter and tighter.

Why not reduce your slides by half and see what happens?

And if that goes well, why not try it with a single slide?

I have never met a presentation with too few slides.

Image credit — NASA Goddard

Meeting Time vs. Thinking Time

How many hours of meetings do you sit through each week? Check your calendar over the previous month and write down that number.

How many hours of meetings do you sit through each week? Check your calendar over the previous month and write down that number.

If you had control over your calendar, would you rather sit through more meetings or fewer?

If you don’t meet enough and need more meetings, I want to work at your company.

If you want fewer, what will you do to change things? Here are two simple things you can try:

- Say no to meetings that have no agenda. Tell them you have a policy to be prepared for all meetings and since you don’t know how to prepare (no agenda!) you’ll sit this one out.

- Say no to meetings where everyone updates each other. Tell them you’ll read the minutes they won’t write.

Check your calendar over the previous month, add the hours you could have saved if you followed the two rules, and divide by four to convert to a weekly average. Write down that number.

How much time do you spend getting ready for meetings each week? Write down that number.

How much time do you spend recovering from meetings each week? (Switching cost is real.) Write down that number.

Now let’s focus on thinking.

How many hours do you think each week? Check your calendar over the previous month, divide by four to convert to a weekly average, and write down that number.

If you had control over your calendar, would you rather think more or less?

If you have too much time to think, I want to work at your company.

If you want to think more, what will you do to change things? Here are two simple things you can try:

- Schedule a one-hour meeting with yourself that recurs weekly. Mark the meeting as “out of office.”

- For the next three weeks, add another recurring meeting with yourself.

And, yes, it’s possible to schedule time to think.

An additional four hours of thinking per week may not sound significant, but it’s probably a 100% increase over your previous weekly average. That’s a big difference especially since everyone else spends most of their time in meetings.

Use the two rules to say no to meetings and you’ll free up a lot of time. And with that freed-up time, you can schedule four hours of thinking time per week.

Why not give it a try? Your career will thank you.

Image credit — Florence Ivy

Improvement In Reverse Sequence

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can make improvements, you must identify improvement opportunities.

Before you can identify improvement opportunities, you must look for them.

Before you can look for improvement opportunities, you must believe improvement is possible.

Before believing improvement is possible, you must admit there’s a need for improvement.

Before you can admit the need for improvement, you must recognize the need for improvement.

Before you can recognize the need for improvement, you must feel dissatisfied with how things are.

Before you can feel dissatisfied with how things are, you must compare how things are for you relative to how things are for others (e.g., competitors, coworkers).

Before you can compare things for yourself relative to others, you must be aware of how things are for others and how they are for you.

Before you can be aware of how things are, you must be calm, curious, and mindful.

Before you can be calm, curious, and mindful, you must be well-rested and well-fed. And you must feel safe.

What choices do you make to be well-rested? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to be well-fed? How do you feel about that?

What choices do you make to feel safe? How do you feel about that?

Image credit — Philip McErlean

How To Make Progress

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improvement is progress. Improvement is always measured against a baseline, so the first thing to do is to establish the baseline, the thing you make today, the thing you want to improve. Create an environment to test what you make today, create the test fixtures, define the inputs, create the measurement systems, and write a formal test protocol. Now you have what it takes to quantify an improvement objectively. Test the existing product to define the baseline. No, you haven’t improved anything, but you’ve done the right first thing.

Improving the right thing to make progress. If the problem invalidates the business model, stop what you’re doing and solve it right away because you don’t have a business if you don’t solve it. Any other activity isn’t progress, it’s dilution. Say no to everything else and solve it. This is how rapid progress is made. If the customer won’t buy the product if the problem isn’t solved, solve it. Don’t argue about priorities, don’t use shared resources, don’t try to be efficient. Be effective. Do one thing. Solve it. This type of discipline reduces time to market. No surprises here.

Avoiding improvement of the wrong thing to make progress. For lesser problems, declare them nuisances and permit yourself to solve them later. Nuisances don’t have to be solved immediately (if at all) so you can double down on the most important problems (speed, speed, speed). Demoting problems to nuisances is probably the most effective way to accelerate progress. Deciding what you won’t do frees up resources and emotional bandwidth to make rapid progress on things that matter.

Work the critical path to make progress. Know what work is on the critical path and what is not. For work on the critical path, add resources. Pull resources from non-critical path work and add them to the critical path until adding more slows things down.

Eliminate waiting to make progress. There can be no progress while you wait. Wait for a tool, no progress. Wait for a part from a supplier, no progress. Wait for raw material, no progress. Wait for a shared resource, no progress. Buy the right tools and keep them at the workstations to make progress. Pay the supplier for priority service levels to make progress. Buy inventory of raw materials to make progress. Ensure shared resources are wildly underutilized so they’re available to make progress whenever you need to. Think fire stations, fire trucks, and firefighters.

Help the team make progress. As a leader, jump right in and help the team know what progress looks like. Praise the crudeness of their prototypes to help them make them cruder (and faster) next time. Give them permission to make assumptions and use their judgment because that’s where speed comes from. And when you see “activity” call it by name so they can recognize it for themselves, and teach them how to turn their effort into progress.

Be relentless and respectful to make progress. Apply constant pressure, but make it sustainable and fun.

Image credit — Clint Mason

What It Means To Stand Tall

People try to diminish when they’re threatened.

People try to diminish when they’re threatened.

People are threatened when they think you’re more capable than they are.

When they think less of themselves, they see you as more capable.

There you have it.

When someone doesn’t do what they say and you bring it up to them, there are two general responses. If they forget, they tell you and apologize. If they don’t have a good reason, they respond defensively.

When someone responds defensively, it means they know what they did.

They respond defensively when they know what they did and don’t like what it says about them.

Defensiveness is an admission of guilt.

Defensiveness is an acknowledgment that the ego was bruised.

Defensiveness is a declaration self-worth is insufficient.

People can either stand down or turn it up when defensiveness is called by name.

When people stand down, they demonstrate they have what it takes to own their behavior.

When they turn it up, they don’t.

When people turn their defensiveness into aggressiveness, they’re unwilling to own their behavior because doing so violates their self-image. And that’s why they’re willing to blame you for their behavior.

When you tell someone they didn’t do what they said and they acknowledge their behavior, praise them. Tell them they displayed courage. Thank them.

When you call someone on their defensiveness and they own their behavior, compliment them for their truthfulness. Tell them their truthfulness is a compliment to you. Tell them their truthfulness means you are important to them.

When you call someone on their defensiveness and they respond aggressively, stand tall. Recognize they are threatened and stand tall. Recognize they don’t like what they did and they don’t have what it takes (in the moment) to own their behavior. And stand tall. When they try to blame you, tell them you did nothing wrong. Tell them it’s not okay to try to blame you for their behavior. And stand tall.

It’s not your responsibility to teach them or help them change their behavior. But it is your responsibility to stay in control, to be professional, and to protect yourself.

When you stand tall, it means you know what they’re doing. When you stand tall, it means it’s not okay to behave that way. When you stand tall, it means you are comfortable describing their behavior to those who can do something about it. When you continue to stand tall, you make it clear there is nothing they can do to prevent you from standing tall.

In the future, they may behave defensively and aggressively with others, but they won’t behave that way with you. And maybe that will help others stand tall.

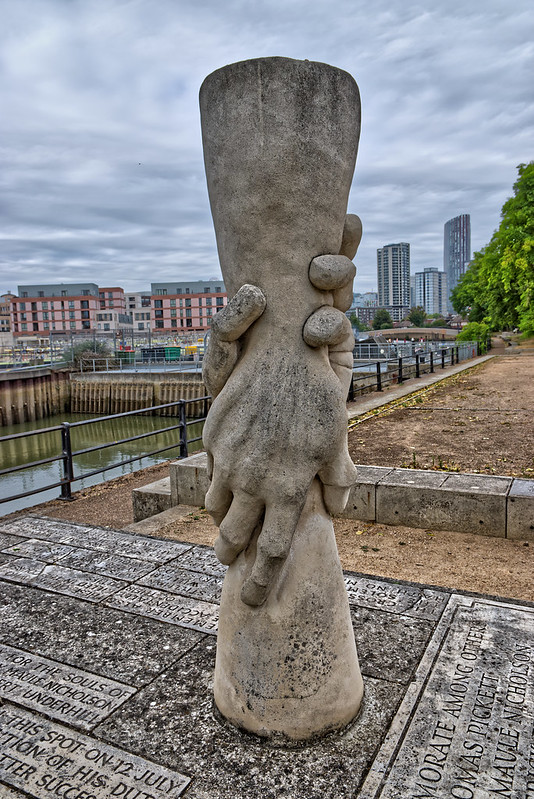

Image credit — Johan Wieland

Wanting What You Have

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

If you got what you wanted, what would you do?

Would you be happy or would you want something else?

Wanting doesn’t have a half-life. Regardless of how much we have, wanting is always right there with us lurking in the background.

Getting what you want has a half-life. After you get what you want, your happiness decays until what you just got becomes what you always had. I think they call that hedonistic adaptation.

When you have what you always had, you have two options. You can want more or you can want what you have. Which will you choose?

When you get what you want, you become afraid to lose what you got. There’s no free lunch with getting what you want.

When you want more, I can manipulate you. I wouldn’t do that, but I could.

When you want more your mind lives in the future where it tries to get what you want. And lives in the past where it mourns what you did not get or lost.

It’s easier to live in the present moment when you want what you have. There’s no need to craft a plan to get more and no need to lament what you didn’t have.

You can tell when a person wants what they have. They are kind because there’s no need to be otherwise. They are calm because things are good. And they are themselves because they don’t need anything from anyone.

Wanting what you have is straightforward. Whatever you have, you decide that’s what you want. It’s much different than having what you want. Once you have what you want hedonistic adaptation makes you want more, and then it’s time to jump back on the hamster wheel.

Wanting what you have is freeing. Why not choose to be free and choose to want what you have?

Image credit — Steven Guzzardi

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski