Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

How do you measure your people?

We get what we measure and, generally, we measure what’s easy to measure and not what will build a bridge to the right behavior.

We get what we measure and, generally, we measure what’s easy to measure and not what will build a bridge to the right behavior.

Timeframe. If we measure people on a daily pitch, we get behavior that is maximized over eight hours. If a job will take nine hours, it won’t get done because the output metrics would suffer. It’s like a hundred-meter sprint race where the stopwatch measures output at one hundred meters. The sprinter spends all her energy sprinting one hundred meters and then collapses. There’s no credit for running further than one hundred meters, so they don’t. Have you ever seen a hundred-meter race where someone ran two hundred meters?

Do you want to sprint one hundred meters five days a week? If so, I hope you only need to run five hundred meters. Do you want to run twenty-five miles per week? If so, you should slow down and run five miles per day for five days. You can check in every day to see if the team needs help and measure their miles on Friday afternoon. And if you want the team to run six miles a day, well, you probably have to allocate some time during the week so they can get stronger, improve their running stride, and do preventative maintenance on their sneakers. For several weeks prior to running six miles a day, you’ve got to restrict their running to four miles a day so they have time to train. In that way, your measurement timeframe is months, not days.

Over what timeframe do you measure your people? And, how do you feel about that?

Control Volume. If you have a fish tank, that’s the control volume (CV) for the fish. If you have two fish tanks, you two control volumes – control volume 1 (CV1) and control volume 2 (CV2). With two control volumes, you can optimize each control volume independently. If tank 1 holds red fish and tank 2 holds blue fish, based on the number of fish in the tanks, you put the right amount of fish food in tank 1 for the red fish and the right amount in tank 2 for the blue fish. The red fish of CV1 live their lives and make baby fish using the food you put in CV1. And to measure their progress, you count the number of red fish in CV1 (tank 1). And it’s the same for the blue fish in CV2.

With the two CVs, you can dial in the recipe to grow the most red fish and dial in a different recipe to grow blue fish. But what if you don’t have enough food for both tanks? If you give more food to the blue fish and starve the red fish, the red fish will get angry and make fewer baby fish. And they will be envious of the blue fish. And, likely, the blue fish will gloat. When CV1 gets fewer resources than CV2, the fish notice.

But what if you want to make purple fish? That would require red fish to jump into the blue tank and even more food to shift from CV1 to CV2. Now the red fish in CV1 are really pissed. And though the red fish moved to tank 2 do their best to make purple guppies with the blue fish, neither color know how to make purple fish. They were never given the tools, time, and training to do this new work. And instead of making purple guppies, usually, they eat each other.

We measure our teams over short timeframes and then we’re dissatisfied when they can’t run marathons. It’s time to look inside and decide what you want. Do you want short-term performance or long-term performance? And, no, you can’t have both from the same team.

And we measure our teams on the output of their control volumes and yet ask them to cooperate and coordinate across teams. That doesn’t work because any effort spent to help another control volume comes at the expense of your own. And the fish know this. And we don’t give them the tools, time, and training to work across control volumes. And the fish know this, too.

“Purple fish” by The Dress Up Place is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

The Illusion of Control

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Unhappy: When you want things to be different than they are.

Happy: When you accept things as they are.

Sad: When you fixate on times when things turned out differently than you wanted.

Neutral: When you know you have little control over how things will turn out.

Anxious: When you fixate on times when things might turn out differently than you want.

Stressed: When you think you have control over how things will turn out.

Relaxed: When you know you don’t have control over how things will turn out.

Agitated: When you live in the future.

Calm: When you live in the present.

Sad: When you live in the past.

Angry: When you expect a just world, but it isn’t.

Neutral: When you expect that it could be a just world, but likely isn’t.

Happy: When you know it doesn’t matter if the world is just.

Angry: When others don’t meet your expectations.

Neutral: When you know your expectations are about you.

Happy: When you have no expectations.

Timid: When you think people will judge you negatively.

Neutral: When you think people may judge you negatively or positively.

Happy: When you know what people think about you is none of your business.

Distracted: When you live in the past or future.

Focused: When you live in the now.

Afraid of change: When you think all things are static.

Accepting change: When you know all things are dynamic.

Intimidated: When you think you don’t meet someone’s expectations.

Confident: When you know you did your best.

Uncomfortable: When you want things to be different than they are.

Comfortable: When you know the Universe doesn’t care what you think.

“Space – Antennae Galaxies” by Trodel is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Musings on Skillfulness

Best practices are good, but dragging projects over the finish line is better.

Best practices are good, but dragging projects over the finish line is better.

Alignment is good, but not when it’s time for misalignment.

Short-term thinking is good, as long as it’s not the only type of thinking.

Reuse of what worked last time is good, as long as it’s bolstered by the sizzle of novelty.

If you find yourself blaming the customer, don’t.

People that look like they can do the work don’t like to hang around with those that can do it.

Too much disagreement is bad, but not enough is worse.

The Status Quo is good at repeating old recipes and better at squelching new ones.

Using your judgment can be dangerous, but not using it can be disastrous.

It’s okay to have some fun, but it’s better to have more.

If it has been done before, let someone else do it.

When stuck on a tricky problem, make it worse and do the opposite.

The only thing worse than using bad judgment is using none at all.

It can be problematic to say you don’t know, but it can be catastrophic to behave as if you do.

The best way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment.

When you don’t know what to do, don’t do it.

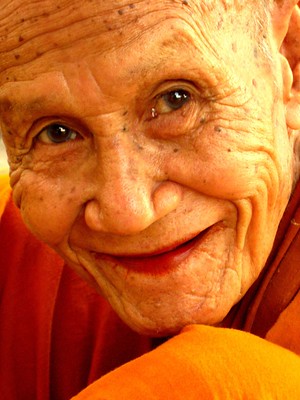

“Old Monk” by anahitox is licensed under CC BY 2.0

What should we do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Anonymous: What do you think we should do next?

Me: It depends. How did you get here?

Anonymous: Well, we’ve had great success improving on what we did last time.

Me: Well, then you’ll likely do that again.

Anonymous: Do you think we’ll be successful this time?

Me: It depends. If the performance/goodness has been flat over your last offerings, then no. When performance has been constant over the last several offerings it means your technology is mature and it’s time for a new one. Has performance been flat over the years?

Anon: Yes, but we’ve been successful with our tried-and-true recipe and the idea of creating a new technology is risky.

Me: All things have a half-life, including successful business models and long-in-the-tooth technologies, and your success has blinded you to the fact that yours are on life support. Developing a new technology isn’t risky. What’s risk is grasping tightly to a business model that’s out of gas.

Anon: That’s harsh.

Me: I prefer “truthful.”

Anon: So, we should start from scratch and create something altogether new?

Me: Heavens no. That would be a disaster. Figure out which elements are blocking new functionality and reinvent those. Hint: look for the system elements that haven’t changed in a dog’s age and that are shared by all your competitors.

Anon: So, I only have to reinvent several elements?

Me: Yes, but probably fewer than several. Probably just one.

Anon: What if we don’t do that?

Me: Over the next five years, you’ll be successful. And then in year six, the wheels will fall off.

Anon: Are you sure?

Me: No, they could fall off sooner.

Anon: How do you know it will go down like that?

Me: I’ve studied systems and technologies for more than three decades and I’ve made a lot of mistakes. Have you heard of The Voice of Technology?

Anon: No.

Me: Well, take a bite of this – The Voice of Technology. Kevin Kelly has talked about this stuff at great length. Have you read him?

Anon: No.

Me: Here’s a beauty from Kevin – What Technology Wants. How about S-curves?

Anon: Nope.

Me: Here’s a little primer – Beyond Dead Reckoning. How about Technology Forecasting?

Anon: Hmm. I don’t think so.

Me: Here’s something from Victor Fey, my teacher. He worked with Altshuller, the creator of TRIZ – Guided Technology Evolution. I’ve used this method to predict several industry-changing technologies.

Anon: Yikes! There’s a lot here. I’m overwhelmed.

Me: That’s good! Overwhelmed is a sign you realize there’s a lot you don’t know. You could be ready to become a student of the game.

Anon: But where do I start?

Me: I’d start Wardley Maps for situation analysis and LEANSTACK to figure out if customers will pay for your new offering.

Anon: With those two I’m good to go?

Me: Hell no!

Anon: What do you mean?

Me: There’s a whole body of work to learn about. Then you’ve got to build the organization, create the right mindset, select the right projects, train on the right tools, and run the projects.

Anon: That sounds like a lot of work.

Me: Well, you can always do what you did last time. END.

“he went that way matey” by jim.gifford is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Just start.

You’re not missing anything. It’s time to start.

You’re not missing anything. It’s time to start.

Afraid to fail? Start anyway.

Don’t have the experience? Well, you won’t be able to say that once you start.

Just start. It’s time.

Don’t have the money? Start small. And if that won’t work, start smaller.

Start small, but start.

Worried about what people might say? There’s only one way to know, so you might as well start.

You’re not an imposter. It’s time to start.

Waiting isn’t waiting, it’s a rationalization to block yourself from starting.

Here’s a rule: If you don’t start you can’t finish.

The only thing in the way of starting is starting.

The fear of success is the strongest stopper of starting. Be afraid of success, and start.

There’s never a good time to start, but there’s always a best time – now.

Worried about the negative consequences of starting? Be worried, and start.

Don’t think you have what it takes? The only way to know for sure is to start.

There’s no way around it. Starting starts with starting.

“Golfland start” by twid is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

It’s time to start starting.

What do we do next? I don’t know

What do we do next? I don’t know

What has been done before?

What does it do now?

What does it want to do next?

If it does that, who cares?

Why should we do it? I don’t know.

Will it increase the top line? If not, do something else.

Will it increase the bottom line? If so, let someone else do it.

What’s the business objective?

Who will buy it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

What does it look like when you know they’ll buy it?

Why do you think it’s okay to do the work before you know they’ll buy it?

What problem must be solved? I don’t know.

How will you define the problem?

Why do you think it’s okay to solve the problem before defining it?

Why do you insist on solving the wrong problem? Don’t you know that ready, fire, aim is bad for your career?

Where’s the functional coupling? When will you learn about Axiomatic Design?

Where is the problem? Between which two system elements?

When does the problem happen? Before what? During what? After what?

Will you separate in time or space?

When will you learn about TRIZ?

Who wants you to do it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

When will you read all the operating plans?

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

Who doesn’t want you to do it? I don’t know.

How will you find out?

Who looks bad if this works?

Who is threatened by the work?

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

What does it look like when it’s done? I don’t know.

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

What do you need to be successful? I don’t know.

Why do you think it’s okay to start the work before knowing this?

Starting is essential, but getting ready to start is even more so.

Image credit — Jon Marshall

What You Don’t Have

If you have more features, I will beat you with fewer.

If you have more features, I will beat you with fewer.

If you have a broad product line, I will beat you with my singular product.

If your solution is big, mine will beat you with small.

If you sell across the globe, I will sell only in the most important market and beat you.

If you sell to many customers, I will provide a better service to your best customer and beat you.

If your new projects must generate $10 million per year, I will beat you with $1 million projects.

If you are slow, I will beat you with fast.

If you use short term thinking, I will beat you with long term thinking.

If you think in the long term, I will think in the short term and beat you.

If you sell a standardized product, I will beat you with customization.

If you are successful, I will beat you with my hunger.

If you try to do less, I will beat you with far less.

If you do what you did last time, I will beat you with novelty.

If you want to be big, I will be a small company and beat you.

I will beat you with what you don’t have.

Then, I will obsolete my best work with what I don’t have.

Your success creates inertia. Your competitors know what you’re good at and know you’ll do everything you can to maintain your trajectory. No changes, just more of what worked. And they will use your inertia. They will start small and sell to the lowest end of the market. Then they’ll grow that segment and go up-scale. You will think they are silly and dismiss them. And then they will take your best customers and beat you.

If you want to know how your competitors will beat you, think of your strength as a weakness. Here’s a thought experiment to explain. If your success is based on fast, turn speed into weakness and constrain out the speed. Declare that your new product must be slow. Then, create a growth plan based on slow. That growth plan is how your competitors will beat you.

Your growth won’t come from what you have, it will come from what you don’t have.

It’s time to create your anti-product.

Why do you go to work?

Why did you go to work today? Did your work bring you meaning? How do you feel about that? Your days are limited. What would it take to slather your work with meaning?

Why did you go to work today? Did your work bring you meaning? How do you feel about that? Your days are limited. What would it take to slather your work with meaning?

Last week, did you make a difference? Did you make a ruckus?

Would you rather strive for the next job, or would you rather make a difference?

Ten years from now, what will be different because of you? Who will remember? How do you feel about that?

Who stands taller because of you?

Do you want to make a difference or do you want the credit?

Do you care what people think or do you do what’s right?

Do you stand front and center when things go badly? Do you sit quietly in the background when things go well? If you don’t, why don’t you do what it takes to develop young talent?

Have you ever done something that’s right for the company but wrong for your career? If you have, many will remember.

What conditions did you create to help people try new things?

Would you rather make the decision yourself or teach others to make good decisions?

Here’s a rule: If you didn’t make a ruckus, you didn’t make a difference.

Last week, did you go with the flow, or did you generate that much-needed turbulence for those that are too afraid to speak up?

What have you given that will stay with someone for the rest of their life?

Do bring your whole self to the work?

If the right people know what you did, can that be enough for you?

At the end of the day, what is different because of you? More importantly, at the end of the day who is different? Who did you praise? Who did you push? Who did you believe in? Who did you teach? Who did you support? Who did you learn from? Who did you thank? Who did you challenge? Who did empathize with? Who were you truthful with? Who did you share with? Who did you listen to?

And how do you feel about that?

Image credit — banoootah_qtr

Two Sides of the Equation

If you want new behavior, you must embrace conflict.

If you want new behavior, you must embrace conflict.

If you can’t tolerate the conflict, you’ll do what you did last time.

If your point of view angers half and empowers everyone else, you made a difference.

If your point of view meets with 100% agreement, you wasted everyone’s time.

If your role is to create something from nothing, you’ve got to let others do the standard work.

If your role is to do standard work, you’ve got to let others create things from scratch.

If you want to get more done in the long term, you’ve got to make time to grow people.

If you want to get more done in the short term, you can’t spend time growing people.

If you do novel work, you can’t know when you’ll be done.

If you are asked for a completion date, I hope you’re not expected to do novel work.

If you’re in business, you’re in the people business.

If you’re not in the people business, you’ll soon be out of business.

If you call someone on their behavior and they thank you, you were thanked by a pro.

If you call someone on their behavior and they call you out for doing it, you were gaslit.

If you can’t justify doing the right project, reduce the scope, and do it under the radar.

If you can’t prevent the start of an unjust project, find a way to work on something else.

If you are given a fixed timeline and fixed resources, flex the schedule.

If you are given a fixed timeline, resources, and schedule, you’ll be late.

If you get into trouble, ask your Trust Network for help.

If you have no Trust Network, you’re in trouble.

If you have a problem, tell the truth and call it a problem.

If you can’t tell the truth, you have a big problem.

If you are called on your behavior, own it.

If you own your behavior, no one can call you on it.

Image credit – Mary Trebilco

No Time for the Truth

Company leaders deserve to know the truth, but they can no longer take the time to learn it.

Company leaders deserve to know the truth, but they can no longer take the time to learn it.

Company leaders are pushed too hard to grow the business and can no longer take the time to listen to all perspectives, no longer take the time to process those perspectives, and no longer take the time to make nuanced decisions. Simply put, company leaders are under too much pressure to grow the business. It’s unhealthy pressure and it’s too severe. And it’s not good for the company or the people that work there.

What’s best for the company is to take the time to learn the truth.

Getting to the truth moves things forward. Sure, you may not see things correctly, but when you say it like you see it, everyone’s understanding gets closer to the truth. And when you do see things clearly and correctly, saying what you see moves the company’s work in a more profitable direction. There’s nothing worse than spending time and money to do the work only to learn what someone already knew.

What’s best for the company is to tell the truth as you see it.

All of us have good intentions but all of us are doing at least two jobs. And it’s especially difficult for company leaders, whose responsibility is to develop the broadest perspective. Trouble is, to develop that broad perspective sometime comes at the expense of digging into the details. Perfectly understandable, as that’s the nature of their work. But subject matter experts (SMEs) must take the time to dig into the details because that’s the nature of their work. SMEs have an obligation to think things through, communicate clearly, and stick to their guns. When asked broad questions, good SMEs go down to bedrock and give detailed answers. And when asked hypotheticals, good SMEs don’t speculate outside their domain of confidence. And when asked why-didn’t-you’s, good SMEs answer with what they did and why they did it.

Regardless of the question, the best SMEs always tell the truth.

SMEs know when the project is behind. And they know the answer that everyone thinks will get the project get back on schedule. And the know the truth as they see it. And when there’s a mismatch between the answer that might get the project back on schedule and the truth as they see it, they must say it like they see it. Yes, it costs a lot of money when the project is delayed, but telling the truth is the fastest route to commercialization. In the short term, it’s easier to give the answer that everyone thinks will get things back on track. But truth is, it’s not faster because the truth comes out in the end. You can’t defy the physics and you can’t transcend the fundamentals. You must respect the truth. The Universe doesn’t care if the truth is inconvenient. In the end, the Universe makes sure the truth carries the day.

We’re all busy. And we all have jobs to do. But it’s always the best to take the time to understand the details, respect the physics, and stay true to the fundamentals.

When there’s a tough decision, understand the fundamentals and the decision will find you.

When there’s disagreement, take the time to understand the physics, even the organizational kind. And the right decision will meet you where you are.

When the road gets rocky, ask your best SMEs what to do, and do that.

When it comes to making good decisions, sometimes slower is faster.

Image credit — Dennis Jarvis

Effectiveness at the Expense of Efficiency

Efficiency is a simple measurement – output divided by resources needed to achieve it. How much did you get done and how many people did you need to do it? What was the return on the investment? How much money did you make relative to how much you had to invest? We have efficiency measurements for just about everything. We are an efficiency-based society.

Efficiency is a simple measurement – output divided by resources needed to achieve it. How much did you get done and how many people did you need to do it? What was the return on the investment? How much money did you make relative to how much you had to invest? We have efficiency measurements for just about everything. We are an efficiency-based society.

It’s easy to create a metric for efficiency. Figure out the output you can measure and divide it by the resources you think you used to achieve it. While a metric like this is easy to calculate, it likely won’t provide a good answer to what we think is the only question worth asking– how do we increase efficiency?

Problem 1. The resources you think are used to produce the output aren’t the only resources you used to generate the output. There are many resources that contributed to the output that you did not measure. And not only that, you don’t know how much those resources actually cost. You can try the tricky trick of fully burdened cost, where the labor rate is loaded with an overhead percentage. But that’s, well, nothing more than an artifact of a contrived accounting system. You can do some other stuff like calculate the opportunity cost of deploying those resources on other projects. I’m not sure what that will get you, but it won’t get you the actual cost of achieving the output you think you achieved.

Problem 2. We don’t measure what’s important or meaningful. We measure what’s easy to measure. And that’s a big problem because you end up beating yourself about the head and shoulders trying to improve something that is easy to measure but not all that meaningful. The biggest problem here is local optimization. You want something easy to measure so you cull out a small fraction of a larger process and increase the output of that small part of the process. The thing is, your customer doesn’t care about the efficiency of that small piece of that process. And, improving that small piece likely doesn’t do anything for the output of the total process. If more products aren’t leaving the factory, you didn’t do anything.

Problem 3. Productivity isn’t all that important. What’s important is effectiveness. If you are highly efficient at the wrong thing, you may be efficient, but you’re also ineffective. If you launch a product in a highly efficient way and no one buys it, your efficiency numbers may be off the charts, but your effectiveness numbers are in the toilet.

We have very few metrics on effectiveness. But here are some questions a good effectiveness metric should help you answer.

- Did we work on the right projects?

- Did we make good decisions?

- Did we put the right people on the projects?

- Did we do what we said we’d do?

- After the project, is the team excited to do a follow-on project?

- Did our customers benefit from our work?

- Do our partners want to work with us again?

- Did we set ourselves up to do our work better next time?

- Did we grow our young talent?

- Did we have fun?

- Do more people like to work at our company?

- Have we developed more trust-based relationships over the last year?

- Have we been more transparent with our workforce this year?

If I had a choice between efficiency and effectiveness, I’d choose effectiveness.

Image credit – Bruce Tuten

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski