Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

The Supreme Court of Technology

The Founding Fathers got it right with three branches: legislative to make laws; judicial to interpret laws; and executive to enforce them. Back then it was all about laws, and the system worked.

The Founding Fathers got it right with three branches: legislative to make laws; judicial to interpret laws; and executive to enforce them. Back then it was all about laws, and the system worked.

What the Founding Fathers could not realize was there was a powerful, pre-chrysalis force more powerful than laws, whose metamorphosis would exploit a gap in the three branch system. Technology has become a force more powerful than laws, and needs its own branch of government. We need a Supreme Court of Technology. (Think Ph.D. instead of J.D.)

Technology is the underpinning of a sustainable economy, an economy where citizens are well-educated, healthy, and happy, and where infrastructure is safe and supports the citizens’ needs. For countries that have it, technology generates the wealth to pay for education, healthcare, and bridges. Back then it was laws; today it’s technology.

The Founding Fathers knew interpretation of laws demanded consistency, consistency that transcended the election cycle, and, with its lifetime appointment, the Supreme Court was the mechanism. And it’s the same with technology: technology demands consistency of direction and consistency of purpose, and for that reason I propose a Supreme Court of Technology.

The Chief Justice of Technology and her Associate Justices set the long term technology policy for the country. They can be derided for its long time horizon, but they cannot be ousted for making the right decisions or their consistency of purpose. The Justices decide how to best spend their annual budget, which is substantial and adjusts with inflation and population. Since they are appointed for life, the Justices tell Congress how it goes with technology (and to stop with all this gridlock gamesmanship) and ask the President for her plan to implement the country’s technology policy. (Technology transcends political parties and election cycles.)

With the Supreme Court of Technology appointed and their first technology plan in place (think environment and energy), the country is on track to generate wealth sufficient to build the best educational system in the world (think creativity, art, science, math, and problem solving) to fuel the next generation of technology leadership.

Make your green programs actionable

There’s a big push to be green. Though we want to be green, we’re not sure how to get there. We’ve got high-level metrics, but they’re not actionable. It’s time to figure out what we can change to be green.

There’s a big push to be green. Though we want to be green, we’re not sure how to get there. We’ve got high-level metrics, but they’re not actionable. It’s time to figure out what we can change to be green.

One way manufacturers can be green is to reduce their carbon footprint. That’s one level deeper than simply “being green,” but it’s not actionable either. Digging deeper, manufacturers can reduce their carbon footprint by generating less greenhouse gases, specifically carbon dioxide. Reducing carbon dioxide production is a good goal, but it’s still not actionable.

Looking deeper, carbon dioxide is the result of burning fossil fuels,

Engineering’s Contribution to the Profit Equation

We all want to increase profits, but sometimes we get caught in the details and miss the big picture:

We all want to increase profits, but sometimes we get caught in the details and miss the big picture:

Profit = (Price – Cost) x Volume.

It’s a simple formula, but it provides a framework to focus on fundamentals. While all parts of the organization contribute to profit in their own way, engineering’s work has a surprisingly broad impact on the equation.

The market sets price, but engineering creates function, and improved function increases the price the market will pay. Design the product to do more, and do it better, and customers will pay more. What’s missing for engineering is an objective measure of what is good to the customer.

I can name that tune in three notes.

More with more doesn’t cut it anymore, just not good enough.

More with more doesn’t cut it anymore, just not good enough.

The behavior we’re looking for can be nicely described by the old TV game show Name That Tune, where two contestants competed to guess the name of a song with the fewest notes. They were read a clue that described a song, and ratcheted down the notes needed to guess it. Here’s the nugget: they challenged themselves to do more with less, they were excited to do more with less, they were rewarded when they did more with less. The smartest, most knowledgeable contestants needed fewer notes. Let me say that again – the best contestants used the fewest notes.

In product design, the number of notes is analogous to part count, but the similarities end there. Those that use the fewest are not considered our best or our most knowledgeable, they’re not rewarded for their work, and our organizations don’t create excitement or a sense of challenge around using the fewest.

For other work, the number of notes is analogous to complexity. Acknowledge those that use the fewest, because their impact ripples through your company, and makes all your work easier.

Work that creates wealth

Today’s biggest problems are difficult to solve and our approach to solving them isn’t helping. Whether it’s healthcare, education, infrastructure, defense, or the economy we never get past the wrong question: “Who’s going to pay for it?

Today’s biggest problems are difficult to solve and our approach to solving them isn’t helping. Whether it’s healthcare, education, infrastructure, defense, or the economy we never get past the wrong question: “Who’s going to pay for it?

With healthcare we argue about costs and taxes – who pays and how much. But we’ve got to move past that argument. The real deal is we create insufficient wealth. (Our inability to pay for healthcare is a symptom.) So the real solution must focus on work that creates wealth, real wealth. I’m not talking about merger and acquisition wealth. I’m talking about real wealth generated by inventing, designing, and making products. I’m talking about manufacturing – creating products out of dirt, rocks, and sticks and selling them for more than the cost to make them. With more manufacturing we can fix healthcare. (I also think we should look deeply at the work of providing healthcare and improve the work.)

With education we argue about costs and taxes – who pays and how much. But we’ve got to move past that argument. The real deal is we create insufficient wealth. (Our inability to pay for education is a symptom.) So the real solution must focus on work that creates wealth, real wealth. I’m not talking about merger and acquisition wealth. I’m talking about real wealth generated by inventing, designing, and making products. I’m talking about manufacturing — creating products. With more manufacturing we can fix education. (I also think we should look deeply at the work of providing education and improve the work.)

With infrastructure we argue about costs and taxes – who pays and how much. But we’ve got to move past that argument. The real deal is we create insufficient wealth. (Our inability to pay for infrastructure is a symptom.) So the real solution must focus on work that creates wealth, real wealth. I’m talking about real wealth generated by inventing, designing, and making products. I’m talking about manufacturing — creating products. With more manufacturing we can fix our infrastructure. (I also think we should look deeply at the work of creating and maintaining infrastructure and improve it.)

With defense we argue about costs and taxes – who pays and how much. But we’ve got to move past that argument. The real deal is we create insufficient wealth. (Our inability to pay for defense is a symptom.) So the real solution must focus on work that creates wealth, real wealth. I’m talking about manufacturing — creating products. With more manufacturing we can fix defense. (I also think we should improve the work of providing defense.)

Pulling it all together, with the economy we argue about taxes – who pays and how much. But we’ve got to move past that argument. The real deal is we create insufficient wealth. (Our economy’s health is a symptom.) So the real solution must focus on work that creates real wealth. I’m talking about manufacturing. With more manufacturing the economy will fix itself.

Thankfully we all have different views on healthcare, education, infrastructure, and defense, and I want to preserve them. (That’s what makes our country great.) However, I think we can all agree that creating more wealth will improve our chances of fixing our big problems.

Let’s do more manufacturing.

I don’t know the question, but the answer is jobs.

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

Some sobering facts: (figure and facts from Matt Slaughter)

- During the Great Recession, US job loss (peak to trough) was 8.4 million payroll jobs were lost (6.1%) and 8.5 million private-sector jobs (7.3%).

- In Sept. 2010 there were 108 million U.S. private-sector payroll jobs, about the same as in March 1999.

- It took 48 months to regain the lost 2.0% of jobs in the 2001 recession. At that rate, the U.S. would again reach 12/07 total payroll jobs around January 2020.

The US has a big problem. And I sure as hell hope we are willing do the hard work and make the hard sacrifices to turn things around.

To me it’s all about jobs. To create jobs, real jobs, the US has got to become a more affordable place to invent, design, and manufacture products. Certainly modified tax policies will help and so will trade agreements to make it easier for smaller companies to export products. But those will take too long. We need something now.

To start, we need affordability through productivity. But not the traditional making stuff productivity, we need inventing and designing productivity.

Here’s the recipe: Invent technology in-country, design and develop desirable products in-country (products that offer real value, products that do something different, products that folks want to buy), make the products in-country, and sell them outside the country. It’s that straightforward.

To me invention/innovation is all about solving technical problems. Solving them more productively creates much needed invention/innovation productivity. The result: more affordable invention/innovation.

To me design productivity is all about reducing product complexity through part count reduction. For the same engineering hours, there are few things to design, fewer things to analyze, fewer to transition to manufacturing. The result: more affordable design.

Though important, we can’t wait for new legislation and trade agreements. To make ourselves more affordable we need to increase productivity of our invention/innovation and design engines while we work on the longer term stuff.

If you’re an engineering leader who wants more about invention/innovation and or design productivity, send me an email at

and use the subject line to let me know which you’re interested in. (Your contact information will remain confidential and won’t be shared with anyone. Ever.)

Together we can turn around the country’s economy.

DoD’s Affordability Eyeball

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

The DoD wants to do the right thing. Secretary Gates wants to save $20B per year over the next five years and he’s tasked Dr. Ash Carter to get it done. In Carter’s September 14th memo titled: “Better Buying Power: Guidance for Obtaining Greater Efficiency and Productivity in Defense Spending” he writes strongly:

…we have a continuing responsibility to procure the critical goods and services our forces need in the years ahead, but we will not have ever-increasing budgets to pay for them.

And, we must

DO MORE WITHOUT MORE.

I like it.

Of the DoD’s $700B yearly spend, $200B is spent on weapons, electronics, fuel, facilities, etc. and $200B on services. Carter lays out themes to reduce both flavors. On services, he plainly states that the DoD must put in place systems and processes. They’re largely missing. On weapons, electronics, etc., he lays out some good themes: rationalization of the portfolio, economical product rates, shorter program timelines, adjusted progress payments, and promotion of competition. I like those. However, his Affordability Mandate misses the mark.

Though his Affordability Mandate is the right idea, it’s steeped in the wrong mindset, steeped in emotional constraints that will limit success. Take a look at his language. He will require an affordability target at program start (Milestone A)

to be treated like a Key Performance Parameter (KPP) such as speed or power – a design parameter not to be sacrificed or comprised without my specific authority.

Implicit in his language is an assumption that performance will decrease with decreasing cost. More than that, he expects to approve cost reductions that actually sacrifice performance. (Only he can approve those.) Sadly, he’s been conditioned to believe it’s impossible to increase performance while decreasing cost. And because he does not believe it, he won’t ask for it, nor get it. I’m sure he’d be pissed if he knew the real deal.

The reality: The stuff he buys is radically over-designed, radically over-complex, and radically cost-bloated. Even without fancy engineering, significant cost reductions are possible. Figure out where the cost is and design it out. And the lower cost, lower complexity designs will work better (fewer things to break and fewer things to hose up in manufacturing). Couple that with strong engineering and improved analytical tools and cost reductions of 50% are likely. (Oh yes, and a nice side benefit of improved performance). That’s right, 50% cost reduction.

Look again at his language. At Milestone B, when a system’s detailed design is begun,

I will require a presentation of a systems engineering tradeoff analysis showing how cost varies as the major design parameters and time to complete are varied. This analysis would allow decisions to be made about how the system could be made less expensive without the loss of important capability.

Even after Milestone A’s batch of sacrificed of capability, at Milestone B he still expects to trade off more capability (albeit the lesser important kind) for cost reduction. Wrong mindset. At Milestone B, when engineers better understand their designs, he should expect another step function increase in performance and another step function decrease of cost. But, since he’s been conditioned to believe otherwise, he won’t ask for it. He’ll be pissed when he realizes what he’s leaving on the table.

For generations, DoD has asked contractors to improve performance without the least consideration of cost. Guess what they got? Exactly what they asked for – ultra-high performance with ultra-ultra-high cost. It’s a target rich environment. And, sadly, DoD has conditioned itself to believe increased performance must come with increased cost.

Carter is a sharp guy. No doubt. Anyone smart enough to reduce nuclear weapons has my admiration. (Thanks, Ash, for that work.) And if he’s smart enough to figure out the missile thing, he’s smart enough to figure out his contractors can increase performance and radically reduces costs at the same time. Just a matter of time.

There are two ways it could go: He could tell contractors how to do it or they could show him how it’s done. I know which one will feel better, but which will be better for business?

Rage against the fundamentals

We all have computer models – economic models, buying models, voting models, thermal, stress, and vibration. A strange thing happens when our models reside in the computer: their output becomes gospel, unchallengeable. And to set the hook, computerized output is bolstered by slick graphics, auto-generated graphs, and pretty colors.

We all have computer models – economic models, buying models, voting models, thermal, stress, and vibration. A strange thing happens when our models reside in the computer: their output becomes gospel, unchallengeable. And to set the hook, computerized output is bolstered by slick graphics, auto-generated graphs, and pretty colors.

Model fundamentals are usually well defined, proven, and grounded – not the problem. The problem is applicability. Do the fundamentals apply? Do they apply in the same way? Do different fundamentals apply? We never ask those questions. That’s the problem.

New folks don’t have the context to courageously challenge fundamentals and more experienced folks have had the imagination flogged out of them. So who’s left to challenge applicability of fundamentals? You know who’s left.

It’s smart folks with courage that challenge fundamentals; it’s people willing to contradict previous success (even theirs) that challenge fundamentals; it’s people willing to extend beyond that challenge fundamentals; it’s people willing to risk their career that challenge fundamentals.

Want to challenge fundamentals? Hire, engage, and support smart folks with courage.

Do you know?

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

There are three categories of knowing: we know we know, we don’t know, and we think we know.

When we know we know – we understand fundamentals, we have a model, we have evidence, we can predict. We can build on this knowledge. We’re not often in this state, but it sure feels good when we are. The trick here is to understand the applicability of the knowledge. Change the inputs, change the system, or change the environment and we must question our knowledge. Do the fundamentals still apply?

When we don’t know – no fundamentals, no model, and no predictions. No danger on building on bad knowledge. Life is uncomplicated. Next task: develop the fundamentals; build a model. We’re in this state more often than we admit, and there’s the danger. It’s politically difficult to say “I don’t know.” But it must be said. Otherwise we’re expected to predict the future and to build on the knowledge (that we don’t have).

When we think we know – no fundamentals, no model, and predictions we bet our businesses on. Danger. It feels just as good as when we know we know, but it shouldn’t. Momentum in the wrong direction and we don’t know it. And we’re likely in this state more often than not. But this is a meta-state, an unstable state. The trick is to push on our knowledge so we tip into one of the other two states. Push on our knowledge so we know if we know.

Do you know the fundamentals? Do you have a model? Can you predict?

Bring It Back

Companies (and countries) are slowly learning that moving manufacturing to low cost countries is a big mistake, a mistake of economy-busting proportion. (More costly than any war.) With labor costs at 10% of product cost, saving 20% on labor yields a staggering 2% cost savings. 2%. Say that out loud. 2%. Are you kidding me? 2%? Really? Moving machines all over the planet for 2%? What about cost increases from longer supply chains, poor quality, and loss of control? Move manufacturing to a country with low cost labor? Are you kidding me? Who came up with that idea? Certainly not a knowledgeable manufacturing person. Don’t chase low cost labor, design it out.

Companies (and countries) are slowly learning that moving manufacturing to low cost countries is a big mistake, a mistake of economy-busting proportion. (More costly than any war.) With labor costs at 10% of product cost, saving 20% on labor yields a staggering 2% cost savings. 2%. Say that out loud. 2%. Are you kidding me? 2%? Really? Moving machines all over the planet for 2%? What about cost increases from longer supply chains, poor quality, and loss of control? Move manufacturing to a country with low cost labor? Are you kidding me? Who came up with that idea? Certainly not a knowledgeable manufacturing person. Don’t chase low cost labor, design it out.

(I feel silly writing this. This is so basic. Blocking-and-tackling. Design 101. But we’ve lost our way, so I will write.)

Use Design for Assembly (DFA) and Design for Manufacturing (DFM) to design out 25-50% of the labor time and make product where you have control. The end. Do it. Do it now. But do it for the right reasons – throughput, and quality. (And there’s that little thing about radical material cost reduction which yield cost savings of 20+%, but that’s for another time).

The real benefit of labor reduction is not dollars, it’s time. Less time, more throughput. Half the labor time, double the throughput. One factory performs like two. Bring it back. Fill your factories. Repeat the mantra and you’ll bring it back:

Half the labor and one factory performs like two.

QC stands for Quality Control. No control, no quality. Ever try to control things from 10 time zones in the past? It does not work. It has not worked. Bring it back. Bring back your manufacturing to improve quality. Your brand will thank you. Put the C back in QC – bring it back.

Forward this to your highest level Design Leaders. Tell them they can turn things around; tell them they’re the only ones who can pull it off; tell them we need; tell them we’re counting on them; tell them we’ll help; tell them to bring it back.

The Dumb-Ass Filter

Companies pursue lots of ideas; some turn out well and some badly. Since we can’t tell with 100% certainty if an idea will work, bad ones are a cost of doing business. And it makes sense to tolerate them. The cost of a few bad ones is well worth the upside of a game-changer. It’s like the VC model.

Companies pursue lots of ideas; some turn out well and some badly. Since we can’t tell with 100% certainty if an idea will work, bad ones are a cost of doing business. And it makes sense to tolerate them. The cost of a few bad ones is well worth the upside of a game-changer. It’s like the VC model.

However, there’s a class that must be avoided at all costs: the dumb-ass idea – an idea we should know will not work before we try it. It’s not a bad idea, it’s beyond stupid, it’s deadly.

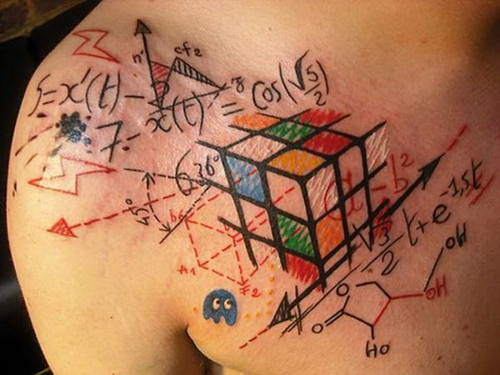

A dumb-ass idea violates fundamentals.

What’s so scary is today’s ready, fire, aim pace makes us more susceptible than ever. Our dumb-ass antibodies need strengthening. We need an immunization, a filter to discern if we’re respecting the fundamentals. We need a dumb-ass filter.

To immunize ourselves it’s helpful to understand how these ideas come to be. Here are some mutant strains:

Local optimization – We improve part of the system at the expense of the overall system. Chasing low cost labor is a good example where labor savings are dwarfed by increased costs of logistics, training, quality, and support.

A cloudy lens – We come up with an idea based on incomplete, biased, or inappropriate data. A good example is financial data which captures cost in a most artificial way. Overhead calculation is the poster child.

Cause and effect – We don’t know which is which; we confuse symptom with root cause and correlation with causation. Expect the unexpected with this mix up.

Scaling – We assume success in the lab is scalable to success across the globe. Everything does not scale, and less scales cost effectively.

Fear – We want to go fast because our competition is already there; we want to go slow because were afraid to fail.

What’s the best dumb-ass filter? It’s a formal and simple definition of the fundamentals. Use one page thinking – fundamentals one page, lots of pictures and few words. There’s no escape.

How to go about it? Settle yourself. Catch your breath. Let your pulse slow. Then, create a one pager (pictures, pictures, pictures) that defines the fundamentals and run it by someone you trust, someone without a vested interest, someone who has learned from their own dumb-ass thinking. (Those folks can spot it at twenty paces.) Defend it to them. Defend it to yourself. Run yourself through the gauntlet.

What are the fundamentals? Do they apply in this situation? How do you know? Answer these and you’re on your way to self-inoculation.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski