Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

Transplant Syndrome

Overall, our upward evolutionary spiral toward infinite productivity is a good thing. (More profit with less work – can’t argue with that.) And also good is our Darwinian desire to increase our chances of realizing profit by winding a thick cocoon of risk reduction around the work.

Overall, our upward evolutionary spiral toward infinite productivity is a good thing. (More profit with less work – can’t argue with that.) And also good is our Darwinian desire to increase our chances of realizing profit by winding a thick cocoon of risk reduction around the work.

But with our productivity helix comes a little known illness that’s rarely diagnosed. It’s not a full-fledged disease, rather, it’s a syndrome. It’s called Transplant Syndrome, or TS.

Along with general flu-like symptoms, TS produces a burning and itching desire to transplant something that worked well in one area into another. On its own, not a bad thing; the dangerous part of TS is that scratching its itch feels so good. And it feels so good because the scratching fits with capitalism’s natural law – only the most productive species will survive.

In a brain suffering from TS, transplanting Region A’s successful business model into Region B makes perfect productivity sense (No new thinking, but plenty of new revenue.) But that’s not the problem. The problem is the TS brain’s urge to transplant is insatiable and indiscriminate. With TS, along with Region B, it makes perfect sense to transplant into Region C, Region D, and Regions L, M, N, O, and P. And with TS, it must happen in record time. Like a parasite, TS feeds on our desire for productivity.

When you transplant your favorite flowering plant from one region of your yard to another, even the inexperienced gardener in us knows to question whether the new region will support the plant. Is the soil similar? Is there enough sun or too much? Will it be blocked from the wind like it is now? And because you know your yard (and because you asked the questions) you won’t transplant unless the viability threshold is met.

But what if you wanted to transplant your most precious flowering plant from your yard in North America to someone else’s yard in South America? At a high level, the viability questions are the same – sun, soil, and water, but the answers are hard to come by. Should you use google to get the answers? Should you get in an airplane and check the territory yourself? Should you talk to the local gardeners? (They don’t speak English.)

But digging deeper, there are many questions you don’t even know to ask. Some of the local bugs may eat your precious plant, so you better know the little crawlies by name and learn what they like to eat. But still, since the bugs have never seen your plant, you won’t know if they’ll eat it until they eat it. You can ask the local gardeners, but they won’t know. (They, too, have never seen it.) Or worse, they may treat it as invasive species and pull it out of the ground after you leave for home.

Here’s an idea. You could scout out local plants that look like yours and declare viability by similarity. But be careful because over the years the local plants have built up tacit defenses you can’t see.

Transplant Syndrome not just a business model syndrome; it infects broadly. In fact, there have been recent outbreaks reported in people that work with products, technologies, processes, and company cultures.

Unfortunately, there is no cure for TS. But, with the right prescription, symptoms can be managed.

Symptoms have been pushed into dormancy when companies hire the best, most experienced, local gardeners. These special gardeners must have been born and raised in-region. And in clinical trials the best results have been achieved when the chief gardener, a well respected local gardener in their own right, has full responsibility for designing, viability testing, and implementing the transplant program.

There have been reported cases of TS symptoms flaring up mid program, but in all cases there was a single common risk factor: no one listened to the gardeners on the receiving end of the transplant.

Accomplishments in 2013 (Year Four)

Accomplishments in 2013

- Fourth year of weekly blog posts without missing a beat or repeating a post. (251 posts in total.)

- Third year of daily tweets – 2,170 in all. (@mikeshipulski)

- Second year as Top 40 Innovation Bloggers (#12) – Innovation Excellence, the web’s top innovation site.

- Seventh consecutive year as Keynote Speaker at International Forum on DFMA.

- Fourth year of LinkedIn working group – Systematic DFMA Deployment.

- Third year writing a column for Assembly Magazine (6 more columns this year).

- Wrote a book — PRODUCT PROCESS PEOPLE – Designing for Change (Which my subscribers can download for free.)

Top 5 Posts

- What They Didn’t Teach Me In Engineering School — a reflection on my learning after my learning.

- Guided Divergence — balancing act of letting go and shaping the future.

- Innovation in 26 words — literally.

- Lasting Behavioral Change — easy to say, tough to do.

- Prototype The Unfamiliar — test early and often.

I look forward to a great year 5.

Define To Solve

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

Countries want their companies to create wealth and jobs, and to do it they want them to design products, make those products within their borders, and sell the products for more than the cost to make them. It’s a simple and sustainable recipe which makes for a highly competitive landscape, and it’s this competition that fuels innovation.

When companies do innovation they convert ideas into products which they make (jobs) and sell (wealth). But for innovation, not any old idea will do; innovation is about ideas that create novel and useful functionality. And standing squarely between ideas and commercialization are tough problems that must be solved. Solve them and products do new things (or do them better), become smaller, lighter, or faster, and people buy them (wealth).

But here’s the part to remember – problems are the precursor to innovation.

Before there can be an innovation you must have a problem. Before you develop new materials, you must have problems with your existing ones; before your new products do things better, you must have a problem with today’s; before your products are miniaturized, your existing ones must be too big. But problems aren’t acknowledged for their high station.

There are problems with problems – there’s an atmosphere of negativity around them, and you don’t like to admit you have them. And there’s power in problems – implicit in them are the need for change and consequence for inaction. But problems can be more powerful if you link them tightly and explicitly to innovation. If you do, problem solving becomes a far more popular sport, which, in turn, improves your problem solving ability.

But the best thing you can do to improve your problem solving is to spend more time doing problem definition. But for innovation not any old problem definition will. Innovation requires level 5 problem definition where you take the time to define problems narrowly and deeply, to define them between just two things, to define when and where problems occur, to define them with sketches and cartoons to eliminate words, and to dig for physical mechanisms.

With the deep dive of level 5 you avoid digging in the wrong dirt and solving the wrong problem because it pinpoints the problem in space and time and explicitly calls out its mechanism. Level 5 problem definition doesn’t define the problem, it defines the solution.

It’s not glamorous, it’s not popular, and it’s difficult, but this deep, mechanism-based problem definition, where the problem is confined tightly in space and time, is the most important thing you can do to improve innovation.

With level 5 problem definition you can transform your company’s profitability and your country’s economy. It does not get any more relevant than that.

Forgotten Pillars of Personal Growth

There are a lot of complex self-help programs out there to help us reach our potential. These programs are designed to take us to the next level by building on what we have. And they do help. But implicitly the programs assume we’ve got a foundation in place and it’s solid enough to stand on. But I think our foundation is rickety.

There are a lot of complex self-help programs out there to help us reach our potential. These programs are designed to take us to the next level by building on what we have. And they do help. But implicitly the programs assume we’ve got a foundation in place and it’s solid enough to stand on. But I think our foundation is rickety.

To be what we must be is our responsibility, and if we’re going to get any value from our self-help programs it’s our responsibility to establish the conditions for growth.

Here are three forgotten pillars that must be in place if we’re to grow:

Good sleep habits – most of us our sleep deprived, yet the data is clear that a rested brain thinks better. If we’re to grow, we’ve got to think better, and to think better we need more rest.

Good eating habits – most of us eat poorly. We eat too much which hurts our bodies and we eat too infrequently which hurts our brains. We all know our muscles need calories or they don’t work well, but what we forget is our brain also needs calories. (It’s 2% of our weight but consumes about 20% of our total calories.) And when we eat infrequently our blood sugar drops and so does our brains’ ability to think. If we’re to grow, we need to eat better.

Good fitness habits – most of us don’t exercise daily. Our brain is connected to our body, and they interact. When the muscles are exercised they cause the brain to make chemicals that sooth and calm. When we exercise we have a better attitude, have more stamina, and think better. If we’re to grow, we need more exercise.

The big three are far more powerful than the best self-help scheme, but they’re also far scarier. They’re so scary because they’re easy to measure and completely within our control.

After a one month trial you’ll know if you’ve slept more, worked out more, and ate better. And if you haven’t, you’ll also know who is responsible.

Circle of Life

Engineers solve technical problems so

Other engineers can create products so

Companies can manufacture them so

They can sell them for a profit and

Use the wealth to pay workers so

Workers can support their families and pay taxes so

Their countries have wealth for good schools to

Grow the next generation of engineers to

Solve the next generation of technical problems so…

Less-With-Far-Less for the Developing World

The stalled world economy will make growth difficult, and companies are digging in for the long haul, getting ready to do more of what they do best – add more function and features, sell more into existing markets, and sell more to existing customers. More of the same, but better. But growth will not come easy with more-on-more thinking. It will be more-on-more trench warfare – ugly hand-to-hand combat with little ground gained. It’s time for another way. It’s time for less. It’s time to create new markets with less-with-far-less thinking.

The stalled world economy will make growth difficult, and companies are digging in for the long haul, getting ready to do more of what they do best – add more function and features, sell more into existing markets, and sell more to existing customers. More of the same, but better. But growth will not come easy with more-on-more thinking. It will be more-on-more trench warfare – ugly hand-to-hand combat with little ground gained. It’s time for another way. It’s time for less. It’s time to create new markets with less-with-far-less thinking.

Real growth will come from markets and consumers that don’t exist. Real (and big) growth will come from the developing world. They’re not buying now, but they will. They will when product are developed that fit them. But here’s the kicker – products for the developed world cannot be twisted and tweaked to fit. Your products must be re-imagined.

The fundamentals are different in the developing world. Three important ones are – ability to pay, population density, and literacy/skill.

The most important fundamental is the developing world’s ability to pay. They will buy, but to buy products must cost 10 to 100 times less. (No typo here – 10 to 100 times less.) Traditional cost reduction approaches such as Design for Manufacturing and Assembly (DFMA) won’t cut it – their 50% cost reductions are not even close. Reinvention is needed; radical innovation is needed; fundamental innovation is needed. Less-with-far-less thinking is needed.

To achieve 10-100X cost reductions, the product must do less and do it far more efficiency (with far less). Product functionality must be decimated – ripped off the bone until only bone remains. The product must do only one thing. Not two – one. The product must be stripped to its essence, and new technology must be developed to radically improve efficiency of delivering its essence. Products for the developing world will require higher levels of technology than products for the developed world.

Radical narrowing of functionality will make viable the smaller, immature, more efficient technologies. Infant technologies usually have lower output and less breadth, but that’s just what’s needed – narrow, deep, and less. Less-with-far-less.

In the developing world, population density is low. People are spread out, and rural is the norm. And it’s not developed world rural, it’s three-day-hike rural. In the developing world, people don’t go to products; products go to people. If it’s not portable, it won’t sell. And developing world portable does not mean wheels – it means backpack. Your products must fit in a backpack and must be light enough to carry in one.

Big, stationary, expensive equipment is not exempt. It also must fit in a backpack. And this cannot be achieved with twist-and-bend engineering. To fit in a backpack, the product must be stripped naked and new technology must be developed to radically improve efficiency. This requires radical narrowing, radical reimagining, and radical innovation. It requires less-with-far-less thinking. (And if it doesn’t run on batteries, it should at least have battery backup to deal with rolling blackouts.)

People in the developing world are intelligent, but most cannot read well and have little experience with developed world products. Where the developed world’s solution is picture-based installation instructions, less-with-far-less products for the developing world demand no instructions. For the developing world, the instruction manual is the on button. And this requires serious technology – software algorithms fed by low cost sensors. And the only way it’s possible is by distilling the product to its essence. Algorithms, yes, but algorithms to do only one thing very well. Less-with-far-less.

The developed world makes products with output that requires judgment – multi-colored graphical output that lets the user decide if things went well. Products for the developing world must have binary output – red/green, beep/no-beep. Less-with-far-less. But again, this seemingly lower-level functionality (a green light versus a digital display) actually requires more technology. The product must interpret results and decide if it’s good – much harder than a sexy graphical output that requires interpretation and judgement.

Creating products for the developing world requires different thinking. Instead of adding more functions and features, it’s about creating new technologies that do one thing very well (and nothing more) and do it with super efficiency. Products for the developing world require higher technologies than those for the developed world. And done well, the developed world will buy them. But the crazy thing is, the less-with-far-less products that will be a hit in the developing world will boomerang back and be an even bigger hit in the developed world.

Small Is Good, And Powerful

If lean has taught us anything, it’s smaller is better. Smaller machines, smaller factories, smaller teams, smaller everything.

If lean has taught us anything, it’s smaller is better. Smaller machines, smaller factories, smaller teams, smaller everything.

The famous Speaker of the House, Tip O’Neill, said all politics are local. He meant all action happens at the lowest levels (in the districts and neighborhoods), where everyone knows everyone, where the issues are well understood, and the fundamentals are not just talked about, they’re lived. It’s the same with manufacturing. But I’m not talking about local in the geography sense; I’m talking about the neighborhood sense. When manufacturing is neighborhood-local, it’s small, tight, focused and knowledgeable.

We mistakenly think about manufacturing strictly as the process of making things—it’s far more. In the broadest sense, manufacturing is everything: innovation, design, making and service. It’s this broad-sense manufacturing that will deliver the next economic revolution.

Previously, I described how big companies break themselves into smaller operating units. They recognize lean favors small, and they break themselves up for competitive advantage. They want to become a collective of small companies with the upside of small without of the downside of big. Yet with small companies, there’s an urge to be big.

Lean says smaller is better and more profitable. Lean says small companies have an advantage because they’re already small. Lean says small companies should stay small (neighborhood small) and be more of what they are.

Small companies have a size advantage. Their smaller scope improves focus and alignment. It’s easier to define the mission, communicate it, and work toward it. It’s easier to mobilize the neighborhood. It’s clearer when things go off track and easier to get things back on track. At the lowest level, smaller companies zero in on problems and fix them. At the highest, they align themselves with their mission. These are important advantages, but not the most important.

The real advantage is deep process knowledge. Smaller companies have less breadth and more depth, which allows them to focus energy on the work and develop deep process knowledge. Many large manufacturers have lost process knowledge over the years. Small companies tend to develop and retain more of it. We’ve forgotten the value of deep process knowledge, but as companies look for competitive advantage, its stock is rising.

Lean wants small companies to build on that strength. To take it to the next level, lean wants companies to think about manufacturing in the more-than-making sense and use that deep process knowledge to influence the product itself. Lean wants suppliers to inject their process knowledge into their customers’ product development process to radically reduce material cost and help the product sprint through the factory.

The ultimate advantage of deep process knowledge is realized when small companies use it to design products. It’s realized when people who know the process fundamentals work respectfully with their neighbors who design the product. The result is deeper process knowledge and a far more profitable product. Big companies like to work with smaller companies who can design and make.

Tip O’Neill and lean agree. All manufacturing is local. And this local nature drives a focus on the fundamentals and details. Being neighborhood-local is easier for small companies because their scope is smaller, which helps them develop and retain deep process knowledge.

Lean wants companies to be small—neighborhood-small. When small companies build on a foundation of deep process knowledge, sales grow. Lean wants sales growth, but it also wants companies to reduce their size in the neighborhood sense.

Make It Where You Sell It

Lean has rolled through our factories and generated profits at every turn. Now it’s time to get serious about savings and realize the next level of savings. Companies are pushing lean into the back office, but that won’t get it done. The savings will be good, but not great. After picking low-hanging factory fruit, there’s uncertainty around what’s next for lean.

Lean has rolled through our factories and generated profits at every turn. Now it’s time to get serious about savings and realize the next level of savings. Companies are pushing lean into the back office, but that won’t get it done. The savings will be good, but not great. After picking low-hanging factory fruit, there’s uncertainty around what’s next for lean.

Make it where you sell it, that’s next for lean. Like a central theorem, this simple phrase will become lean’s mantra, and it will change everything, including our organizations themselves. The big multi-national companies have already started their journey, and we can take our cues from them.

The major automakers have assembly plants on all continents – objective evidence of make it where you sell it. There are many benefits to make it where you sell it, but the top three are: speed, speed, speed. The automotive value stream without make it where you sell it: make a car, put it on a boat, deliver it to a dealer, and sell it. Make it where you sell it eliminates the boat: make it, deliver it, and sell it. Inventory is proportional to cycle time and eliminating the long boat ride shortens the value stream, improves response time and reduces inventory.

Make it where you sell it starts closest to the customer, and final assembly is the first to be established in-market. Engines and transmissions still ride the boat, but not for long. After final assembly, make it where you sell it targets big, heavy, expensive subassemblies, so expect in-market engine and transmission plants. (However, big ones like these may stay put for while due to technological, political, or cultural reasons.)

With one piece flow, right-sized machines, and short product runs, lean has taught us the most economic scale is far smaller than we’d imagined. We’ve learned for our factories smaller is better, and make it where you sell it extrapolates smaller-is-better to the organization itself. Here again, the big guys lead the way. Multinationals are breaking themselves into smaller units, right-sizing into smaller regional companies – still big, but smaller. Their in-country manufacturing creates nice tight feedback loops between customer and factory. And there’s an important benefit to the brand – it becomes a local brand. Not only can the brand better serve regional tastes, it provides goodwill in the form of jobs.

[Disclaimer: I don’t advocate outsourcing. I’m simply explaining the forces at work and their consequences.]

Lean cares about speed, not countries, and make it where you sell it causes jobs flow across company boarders. This is especiallylevant as countries compete for manufacturing jobs like their survival depended on them. For those countries that understand manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of a sustainable economy, make it where you sell it can be threatening. If you’re a country that doesn’t buy a lot of manufactured goods, you and your economy trouble – jobs will flow to where products are sold.

Make it where you sell it won’t stop at making, and will extend up stream. The next logical extension is design it where you sell it, R&D it where you sell it, and innovate it where you sell it. (The biggest companies are already doing this with regional R&D centers.) More jobs will flow across borders, but this time they’ll be the coveted thinking jobs.

Make it where you sell it is the guiding principle companies are using to become more responsive, more productive, and local. It has already broken the biggest companies into smaller ones. They’ve realized that the most economic scale is small, and they’re getting there using make it where you sell it.

Make it where you sell it will change all companies, even small ones. And the mantra for small companies: think narrow and deep.

I will hold a half-day Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Heroes of the Company

If I was a company, the first thing I’d do is invest in my engineering teams. But not for the reasons we normally associate with engineering. Not for more function and features, not for product robustness, not technology, and not patents. I would invest in engineering for increased profits.

If I was a company, the first thing I’d do is invest in my engineering teams. But not for the reasons we normally associate with engineering. Not for more function and features, not for product robustness, not technology, and not patents. I would invest in engineering for increased profits.

When it comes to their engineering divisions, other companies think minimization – fewest heads, lowest wages, least expensive tools. Not me. I’m all about maximization – smartest, best trained, and the best tools. That’s how I like to maximize profits. To me, investing in my engineering teams gives me the highest return on my investment.

Engineers create the products I sell to my customers. I’ve found when my best engineers sit down and think for a while they come up with magical ideas that translate into super-performing products, products with features that differentiate me from my cousin companies, and products that flat-out don’t break. My sales teams love to sell them (Sure, I pay a lot in bonuses, but it’s worth it.), my marketing teams love to market them, and my factory folks build them with a smile.

Over my life I’ve developed some simple truisms that I live by: When I sell more products, I make more profits; when my products allow a differentiated marketing message, I sell more and make more profits; and when my product jumps together, my quality is better, and, you guessed it, I make more profits. All these are good reasons to invest in engineering, but it’s not my reason. All this increased sales stuff is good, but it’s not great. It’s not my real reason to invest in engineering. It’s not my secret.

When I was younger I vowed to take my secret to the grave, but now that I’ve matured (and filled up several banks with money), I think it’s okay to share it. So, here goes.

My real reason to invest in engineering is material cost reduction. Yes, material cost reduction. My materials budget is one of my largest line items and I help my engineers reduce it with reckless abandon (and the right tools, time, training, and teacher.) I’ve asked my lean folks to reduce material cost, but they’ve not been able to dent it. Sure, they’ve done a super job with inventory reduction (I get a one-time carrying cost reduction.), but no material cost reduction from my lean projects. I’ve also asked my six sigma organization to reduce material costs, but they, too, have not made a dent. They’ve improved my product quality, but that doesn’t translate into piles of money like material cost reduction.

Now, I know what you’re thinking: Why, Mrs. Company, are you wasting engineering’s time with cost? Cost is manufacturing’s responsibility – they should reduce it, not engineering. Plain and simple – that’s not what I believe, and neither do my engineers. They know they create cost to enable function, good material cost – worth every penny. But they also know all other cost is bad. And since they know they design in cost, they know they’re the ones that must design it out. And they’re good at it. With the right tools, time, and training, they typically reduce material costs by 50%. Do the math –material cost for your highest volume product times 50% – year-on-year. Piles of money.

I’ve learned over the years increasing sales is difficult and takes a lot of work. I’ve also learned I can make lots of money reducing material costs without increasing sales. In fact, even during the recent downturn, through my material cost reductions I made more money than ever. I have my design engineers to thank for that.

Company-to-company, I know things have been tough for us over the last years, and money is still tight. But if you have a little extra stashed away, I urge you to invest in your engineering organization. It makes for great profits.

Seeing Things As They Are

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

It’s tough out there. Last year we threw the kitchen sink at our processes and improved them, and now last year’s improvements are this year’s baseline. And, more significantly, competition has increased exponentially – there are more eager countries at the manufacturing party. More countries have learned that manufacturing jobs are the bedrock of sustainable economy. They’ve designed country-level strategies and multi-decade investment plans (education, infrastructure, and energy technologies) to go after manufacturing jobs as if their survival depended on them. And they’re not just making, they’re designing and making. Country-level strategies and investments, designing and making, and citizens with immense determination to raise their standard of living – a deadly cocktail. (Have you seen Hyundai’s cars lately?)

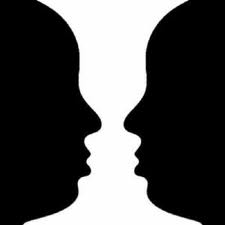

With the wicked couple of competition and profitability goals, we’re under a lot of pressure. And with the pressure comes the danger of seeing things how we want them instead of how they are, like a self-created optical illusion. Here are some likely optical illusion A-B pairs (A – how we want things; B – how they are):

A. Give people more work and more gets done. B. Human output has a physical limit, and once reached less gets done – and spouses get angry. A. Do more projects in parallel to generate more profit. B. Business processes have physical limits, and once reached projects slow and everyone works harder for the same output. A. Add resources to the core project team and more projects get done. B. Add resources to core projects teams and utilization skyrockets for shared resources – waiting time increases for all. A. Use lean in product development (just like in manufacturing) to launch new products better and faster. B. Lean done in product development is absolutely different than in manufacturing, and design engineers don’t take kindly to manufacturing folks telling them how to do their work. A. Through negotiation and price reduction, suppliers can deliver cost reductions year-on-year. B. The profit equation has a physical limit (no profit), and once reached there is no supplier. A. Use lean to reduce product cost by 5%. B. Use DFMA to reduce product cost by 50%.Competition is severe and the pressure is real. And so is the danger to see things as we want them to be. But there’s a simple way to see things as they are: ask the people that do the work. Go to the work and ask the experts. They do the work day-in-day-out, and they know what really happens. They know the details, the pinch points, and the critical interactions.

To see things as they are, check your ego at the door, and go ask the experts – the people that do the work.

How To Create a Sea of Manufacturing Jobs

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

It’s been a long slide from greatness for US manufacturing. It’s been downhill since the 70s – a multi-decade slide. Lately there’s a lot of hype about a manufacturing renaissance in the US – re-shoring, on-shoring, right-shoring. But the celebration misguided. A real, sustainable return to greatness will take decades, decades of single-minded focus, coordination, alignment and hard work – industry, government, and academia in it together for the long haul.

To return to greatness, the number of new manufacturing jobs to be created is distressing. 100,000 new manufacturing jobs is paltry. And today there is a severe skills gap. Today there are unfilled manufacturing jobs because there’s no one to do the work. No one has the skills. With so many without jobs it sad. No, it’s a shame. And the manufacturing talent pipeline is dry – priming before filling. Creating a sea of new manufacturing jobs will be hard, but filling them will be harder. What can we do?

The first thing to do is make list of all the open manufacturing jobs and categorize them. Sort them by themes: by discipline, skills, experience, tools. Use the themes to create training programs, train people, and fill the open jobs. (Demonstrate coordinated work of government, industry, and academia.) Then, using the learning, repeat. Define themes of open manufacturing jobs, create training programs, train, and fill the jobs. After doing this several times there will be sufficient knowledge to predict needed skills and proactive training can begin. This cycle should continue for decades.

Now the tough parts – transcending our short time horizon and finding the money. Our time horizon is limited to the presidential election cycle – four years, but the manufacturing rebirth will take decades. Our four year time horizon prevents success. There needs to be a guiding force that maintains consistency of purpose – manufacturing resurgence – a consistency of purpose for decades. And the resurgence cannot require additional money. (There isn’t any.) So who has a long time horizon and money?

The DoD has both – the long term view (the military is not elected or appointed) and the money. (They buy a lot of stuff.) Before you call me a war hawk, this is simply a marriage of convenience. I wish there was, but there is no better option.

The DoD should pull together their biggest contractors (industry) and decree that the stuff they buy will have radically reduced cost signatures and teach them and their sub-tier folks how to get it done. No cost reduction, no contract. (There’s no reason military stuff should cost what it does, other than the DoD contractors don’t know how design things cost effectively.) The DoD should educate their contractors how to design products to reduce material cost, assembly time, supply chain complexity, and time to market and demand the suppliers. Then, demand they demonstrate the learning by designing the next generation stuff. (We mistakenly limit manufacturing to making, when, in fact, radical improvement is realized when we see manufacturing as designing and making.)

The DoD should increase its applied research at the expense of its basic research. They should fund applied research that solves real problems that result in reduced cost signatures, reduce total cost of ownership, and improved performance. Likely, they should fund technologies to improve engineering tools, technologies that make themselves energy independent and new materials. Once used in production-grade systems, the new technologies will spill into non-DoD world (broad industry application) and create new generation products and a sea of manufacturing jobs.

I think this is approach has a balanced time horizon – fill manufacturing jobs now and do the long term work to create millions of manufacturing jobs in the future.

Yes, the DoD is at the center of the approach. Yes, some have a problem with that. Yes, it’s a marriage of convenience. Yes, it requires coordination among DoD, industry, and academia. Yes, that’s almost impossible to imagine. Yes, it requires consistency of purpose over decades. And, yes, it’s the best way I know.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski