Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

The Top Three Enemies of Innovation – Waiting, Waiting, Waiting

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

All innovation projects take longer than expected and take more resources than expected. It’s time to change our expectations.

With regard to time and resources, innovation’s biggest enemy is waiting. There. I said it.

There are books and articles that say innovation is too complex to do quickly, but complexity isn’t the culprit. It’s true there’s a lot of uncertainty with innovation, but, uncertainty isn’t the reason it takes as long as it does. Some blame an unhealthy culture for innovation’s long time constant, but that’s not exactly right. Yes, culture matters, but it matters for a very special reason. A culture intolerant of innovation causes a special type of waiting that, once eliminated, lets innovation to spool up to break-neck speeds.

Waiting? Really? Waiting is the secret? Waiting isn’t just the secret, it’s the top three secrets.

In a backward way, our incessant focus on productivity is the root cause for long wait times and, ultimately, the snail’s pace of innovation. Here’s how it goes. Innovation takes a long time so productivity and utilization are vital. (If they’re key for manufacturing productivity they must be key to innovation productivity, right?) Utilization of fixed assets – like prototype fabrication and low volume printed circuit board equipment – is monitored and maximized. The thinking goes – Let’s jam three more projects into the pipeline to get more out of our shared resources. The result is higher utilizations and skyrocketing queue times. It’s like company leaders don’t believe in queuing theory. Like with global warming, the theory is backed by data and you can’t dismiss queuing theory because it’s inconvenient.

One question: If over utilization of shared resources delays each prototype loop by two weeks (creates two weeks of incremental wait time) and you cycle through 10 prototype loops for each innovation project, how many weeks does it delay the innovation project? If you said 20 weeks you’re right, almost. It doesn’t delay just that one project; it delays all the projects that run through the shared resource by 20 weeks. Another question: How much is it worth to speed up all your innovation projects by 20 weeks?

In a second backward way, our incessant drive for productivity blinds us of the negative consequences of waiting. A prototype is created to determine viability of a new technology, and this learning is on the project’s critical path. (When the queue time delays the prototype loop by two weeks, the entire project slips two weeks.) Instead of working to reduce the cycle time of the prototype loop and advance the critical path, our productivity bias makes us work on non-critical path tasks to fill the time. It would be better to stop work altogether and help the company feel the pain of the unnecessarily bloated queue times, but we fill the time with non-critical path work to look busy. The result is activity without progress, and blindness to the reason for the schedule slip – waiting for the over utilized shared resource.

A company culture intolerant of uncertainty causes the third and most destructive flavor of waiting. Where productivity and over utilization reduce the speed of innovation, a culture intolerant of uncertainty stops innovation before it starts. The culture radiates negative energy throughout the labs and blocks all experiments where the results are uncertain. Blocking these experiments blocks the game-changing learning that comes with them, and, in that way, the culture create infinite wait time for the learning needed for innovation. If you don’t start innovation you can never finish. And if you fix this one, you can start.

To reduce wait time, it’s important to treat manufacturing and innovation differently. With manufacturing think efficiency and machine utilization, but with innovation think effectiveness and response time. With manufacturing it’s about following an established recipe in the most productive way; with innovation it’s about creating the new recipe. And that’s a big difference.

If you can learn to see waiting as the enemy of innovation, you can create a sustainable advantage and a sustainable company. It’s time to change expectations around waiting.

Image credit – Pulpolux !!!

Systematic Innovation

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

Innovation is a journey, and it starts from where you are. With a systematic approach, the right information systems are in place and are continuously observed, decision makers use the information to continually orient their thinking to make better and faster decisions, actions are well executed, and outcomes of those actions are fed back into the observation system for the next round of orientation. With this method, the organization continually learns as it executes – its thinking is continually informed by its environment and the results of its actions.

To put one of these innovation systems in place, the first step is to define the group that will make the decisions. Let’s call them the Decision Group, or DG for short. (By the way, this is the same group that regularly orients itself with the information steams.) And the theme of the decisions is how to deploy the organization’s resources. The decision group (DG) should be diverse so it can see things from multiple perspectives.

The DG uses the company’s mission and growth objectives as their guiding principles to set growth goals for the innovation work, and those goals are clearly placed within the context of the company’s mission.

The first action is to orient the DG in the past. Resources are allocated to analyze the product launches over the past ten years and determine the lines of ideality (themes of goodness, from the customers’ perspective). These lines define the traditional ideality (traditional themes of goodness provided by your products) are then correlated with historical profitability by sales region to evaluate their importance. If new technology projects provide value along these traditional lines, the projects are continuous improvement projects and the objective is market share gain. If they provide extreme value along traditional lines, the projects are of the dis-continuous improvement flavor and their objective is to grow the market. If the technology projects provide value along different lines and will be sold to a different customer base, the projects could be disruptive and could create new markets.

The next step is to put in place externally focused information streams which are used for continuous observation and continual orientation. An example list includes: global and regional economic factors, mergers/acquisitions/partnerships, legal changes, regulatory changes, geopolitical issues, competitors’ stock price and quarterly updates, and their new products and patents. It’s important to format the output for easy visualization and to make collection automatic.

Then, internally focused information streams are put in place that capture results from the actions of the project team and deliver them, as inputs, for observation and orientation. Here’s an example list: experimental results (technology and market-centric), analytical results (technical and market), social media experiments, new concepts from ideation sessions (IBEs), invention disclosures, patent filings, acquisition results, product commercialization results and resulting profits. These information streams indicate the level of progress of the technology projects and are used with the external information streams to ground the DG’s orientation in the achievements of the projects.

All this infrastructure, process, and analysis is put in place to help the DG make good (and fast) decisions about how to allocate resources. To make good decisions, the group continually observes the information streams and continually orients themselves in the reality of the environment and status of the projects. At this high level, the group decides not how the project work is done, rather what projects are done. Because all projects share the same resource pool, new and existing projects are evaluated against each other. For ongoing work the DG’s choice is – stop, continue, or modify (more or less resources); and for new work it’s – start, wait, or never again talk about the project.

Once the resource decision is made and communicated to the project teams, the project teams (who have their own decision groups) are judged on how well the work is executed (defined by the observed results) and how quickly the work is done (defined by the time to deliver results to the observation center.)

This innovation system is different because it is a double learning loop. The first one is easy to see – results of the actions (e.g., experimental results) are fed back into the observation center so the DG can learn. The second loop is a bit more subtle and complex. Because the group continuously re-orients itself, it always observes information from a different perspective and always sees things differently. In that way, the same data, if observed at different times, would be analyzed and synthesized differently and the DG would make different decisions with the same data. That’s wild.

The pace of this double learning loop defines the pace of learning which governs the pace of innovation. When new information from the streams (internal and external) arrive automatically and without delay (and in a format that can be internalized quickly), the DG doesn’t have to request information and wait for it. When the DG makes the resource-project decisions it’s always oriented within the context of latest information, and they don’t have to wait to analyze and synthesize with each other. And when they’re all on the same page all the time, decisions don’t have to wait for consensus because it already has. And when the group has authority to allocate resources and chooses among well-defined projects with clear linkage to company profitability, decisions and actions happen quickly. All this leads to faster and better innovation.

There’s a hierarchical set of these double learning loops, and I’ve described only the one at the highest level. Each project is a double learning loop with its own group of deciders, information streams, observation centers, orientation work and actions. These lower level loops are guided by the mission of the company, goals of the innovation work, and the scope of their projects. And below project loops are lower-level loops that handle more specific work. The loops are fastest at the lowest levels and slowest at the highest, but they feed each other with information both up the hierarchy and down.

The beauty of this loop-based innovation system is its flexibility and adaptability. The external environment is always changing and so are the projects and the people running them. Innovation systems that employ tight command and control don’t work because they can’t keep up with the pace of change, both internally and externally. This system of double loops provides guidance for the teams and sufficient latitude and discretion so they can get the work done in the best way.

The most powerful element, however, is the almost “living” quality of the system. Over its life, through the work itself, the system learns and improves. There’s an organic, survival of the fittest feel to the system, an evolutionary pulse, that would make even Darwin proud.

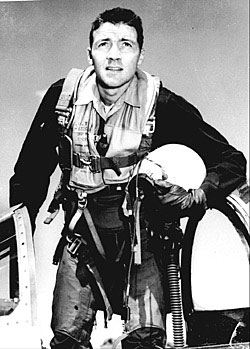

But, really, it’s Colonel John Boyd who should be proud because he invented all this. And he called it the OODA loop. Here’s his story – Boyd: The Fighter Pilot Who Changed the Art of War.

Where possible, I have used Boyd’s words directly, and give him all the credit. Here is a list of his words: observe, orient, decide, act, analyze-synthesize, double loop, speed, organic, survival of the fittest, evolution.

Image attribution – U.S. Government [public domain]. by wikimedia commons.

Clarity is King

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

It all starts and ends with clarity. There’s not much to it, really. You strip away all the talk and get right to the work you’re actually doing. Not the work you should do, want to do, or could do. The only thing that matters is the work you are doing right now. And when you get down to it, it’s a short list.

There’s a strong desire to claim there’s a ton of projects happening all at once, but projects aren’t like that. Projects happen serially. Start one, finish one is the best way. Sure it’s sexy to talk about doing projects in parallel, but when the rubber meets the road, it’s “one at time” until you’re done.

The thing to remember about projects is there’s no partial credit. If a project is half done, the realized value is zero, and if a project is 95% done, the realized value is still zero (but a bit more frustrating). But to rationalize that we’ve been working hard and that should count for something, we allocate partial credit where credit isn’t due. This binary thinking may be cold, but it’s on-the-mark. If your new product is 90% done, you can’t sell it – there is no realized value. Right up until it’s launched it’s work in process inventory that has a short shelf like – kind of like ripe tomatoes you can’t sell. If your competitor launches a winner, your yet-to-see-day light product over-ripens.

Get a pencil and paper and make the list of the active projects that are fully staffed, the ones that, come hell or high water, you’re going to deliver. Short list, isn’t it? Those are the projects you track and report on regularly. That’s clarity. And don’t talk about the project you’re not yet working on because that’s clarity, too.

Are those the right projects? You can slice them, categorize them, and estimate the profits, but with such a short list, you don’t need to. Because there are only a few active projects, all you have to do is look at the list and decide if they fit with company expectations. If you have the right projects, it will be clear. If you don’t, that will be clear as well. Nothing fancy – a list of projects and a decision if the list is good enough. Clarity.

How will you know when the projects are done? That’s easy – when the resources start work on the next project. Usually we think the project ends when the product launches, but that’s not how projects are. After the launch there’s a huge amount of work to finish the stuff that wasn’t done and to fix the stuff that was done wrong. For some reason, we don’t want to admit that, so we hide it. For clarity’s sake, the project doesn’t end until the resources start full-time work on the next project.

How will you know if the project was successful? Before the project starts, define the launch date and using that launch data, set a monthly profit target. Don’t use units sold, units shipped, or some other anti-clarity metric, use profit. And profit is defined by the amount of money received from the customer minus the cost to make the product. If the project launches late, the profit targets don’t move with it. And if the customer doesn’t pay, there’s no profit. The money is in the bank, or it isn’t. Clarity.

Clarity is good for everyone, but we don’t behave that way. For some reason, we want to claim we’re doing more work than we actually are which results in mis-set expectations. We all know it’s matter of time before the truth comes out, so why not be clear? With clarity from the start, company leaders will be upset sooner rather than later and will have enough time to remedy the situation.

Be clear with yourself that you’re highly capable and that you know your work better than anyone. And be clear with others about what you’re working on and what you’re not. Be clear about your test results and the problems you know about (and acknowledge there are likely some you don’t know about).

I think it all comes down to confidence and self-worth. Have the courage wear clarity like a badge of honor. You and your work are worth it.

Image credit – Greg Foster

Innovation Fortune Cookies

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If they made innovation fortune cookies, here’s what would be inside:

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long.

Whether you like it or not, when you start something new uncertainty carries the day.

Don’t define the idealized future state, advance the current state along its lines of evolutionary potential.

Try new things then do more of what worked and less of what didn’t.

Without starting, you never start. Starting is the most important part

Perfection is the enemy of progress, so are experts.

Disruption is the domain of the ignorant and the scared.

Innovation is 90% people and the other half technology.

The best training solves a tough problem with new tools and processes, and the training comes along for the ride.

The only thing slower than going too slowly is going too quickly.

An innovation best practice – have no best practices.

Decisions are always made with judgment, even the good ones.

image credit – Gwen Harlow

To make the right decision, use the right data.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

When it’s time for a tough decision, it’s time to use data. The idea is the data removes biases and opinions so the decision is grounded in the fundamentals. But using the right data the right way takes a lot of disciple and care.

The most straightforward decision is a decision between two things – an either or – and here’s how it goes.

The first step is to agree on the test protocols and measure systems used to create the data. To eliminate biases, this is done before any testing. The test protocols are the actual procedural steps to run the tests and are revision controlled documents. The measurement systems are also fully defined. This includes the make and model of the machine/hardware, full definition of the fixtures and supporting equipment, and a measurement protocol (the steps to do the measurements).

The next step is to create the charts and graphs used to present the data. (Again, this is done before any testing.) The simplest and best is the bar chart – with one bar for A and one bar for B. But for all formats, the axes are labeled (including units), the test protocol is referenced (with its document number and revision letter), and the title is created. The title defines the type of test, important shared elements of the tested configurations and important input conditions. The title helps make sure the tested configurations are the same in the ways they should be. And to be doubly sure they’re the same, once the graph is populated with the actual test data, a small image of the tested configurations can be added next to each bar.

The configurations under test change over time, and it’s important to maintain linkage between the test data and the tested configuration. This can be accomplished with descriptive titles and formal revision numbers of the test configurations. When you choose design concept A over concept B but unknowingly use data from the wrong revisions it’s still a data-driven decision, it’s just wrong one.

But the most important problem to guard against is a mismatch between the tested configuration and the configuration used to create the cost estimate. To increase profit, test results want to increase and costs wants to decrease, and this natural pressure can create divergence between the tested and costed configurations. Test results predict how the configuration under test will perform in the field. The cost estimate predicts how much the costed configuration will cost. Though there’s strong desire to have the performance of one configuration and the cost of another, things don’t work that way. When you launch you’ll get the performance of AND cost of the configuration you launched. You might as well choose the configuration to launch using performance data and cost as a matched pair.

All this detail may feel like overkill, but it’s not because the consequences of getting it wrong can decimate profitability. Here’s why:

Profit = (price – cost) x volume.

Test results predict goodness, and goodness defines what the customer will pay (price) and how many they’ll buy (volume). And cost is cost. And when it comes to profit, if you make the right decision with the wrong data, the wheels fall off.

Image credit – alabaster crow photographic

Prototypes Are The Best Way To Innovate

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

If you’re serious about innovation, you must learn, as second nature, to convert your ideas into prototypes.

Funny thing about ideas is they’re never fully formed – they morph and twist as you talk about them, and as long as you keep talking they keep changing. Evolution of your ideas is good, but in the conversation domain they never get defined well enough (down to the nuts-and-bolts level) for others (and you) to know what you’re really talking about. Converting your ideas into prototypes puts an end to all the nonsense.

Job 1 of the prototype is to help you flesh out your idea – to help you understand what it’s all about. Using whatever you have on hand, create a physical embodiment of your idea. The idea is to build until you can’t, to build until you identify a question you can’t answer. Then, with learning objective in hand, go figure out what you need to know, and then resume building. If you get to a place where your prototype fully captures the essence of your idea, it’s time to move to Job 2. To be clear, the prototype’s job is to communicate the idea – it’s symbolic of your idea – and it’s definitely not a fully functional prototype.

Job 2 of the prototype is to help others understand your idea. There’s a simple constraint in this phase – you cannot use words – you cannot speak – to describe your prototype. It must speak for itself. You can respond to questions, but that’s it. So with your rough and tumble prototype in hand, set up a meeting and simply plop the prototype in front of your critics (coworkers) and watch and listen. With your hand over your mouth, watch for how they interact with the prototype and listen to their questions. They won’t interact with it the way you expect, so learn from that. And, write down their questions and answer them if you can. Their questions help you see your idea from different perspectives, to see it more completely. And for the questions you cannot answer, they the next set of learning objectives. Go away, learn and modify your prototype accordingly (or build a different one altogether). Repeat the learning loop until the group has a common understanding of the idea and a list of questions that only a customer can answer.

Job 3 is to help customers understand your idea. At this stage it’s best if the prototype is at least partially functional, but it’s okay if it “represents” the idea in clear way. The requirement is prototype is complete enough for the customer can form an opinion. Job 3 is a lot like Job 2, except replace coworker with customer. Same constraint – no verbal explanation of the prototype, but you can certainly answer their direction questions (usually best answered with a clarifying question of your own such as “Why do you ask?”) Capture how they interact with the prototype and their questions (video is the best here). Take the data back to headquarters, and decide if you want to build 100 more prototypes to get a broader set of opinions; build 1000 more and do a small regional launch; or scrap it.

Building a prototype is the fastest, most effective way to communicate an idea. And it’s the best way to learn. The act of building forces you to make dozens of small decisions to questions you didn’t know you had to answer and the physical nature the prototype gives a three dimensional expression of the idea. There may be disagreement on the value of the idea the prototype stands for, but there will be no ambiguity about the idea.

If you’re not building prototypes early and often, you’re not doing innovation. It’s that simple.

Inspiration, Imagination, and Innovation – in that order.

Inspiration is the fuel for imagination and imagination is the power behind innovation.

Inspiration is the fuel for imagination and imagination is the power behind innovation.

All companies want innovation and try lots of stuff to increase its supply. But innovation isn’t a thing in itself and not something to be conjured from air – it’ a result of something. The backplane of innovation, its forcing function, is imagination.

But imagination is no longer a sanctioned activity. Since it’s not a value-added activity; and our financial accounting system has no column for it; and it’s unpredictable, it has been leaned out of our work. (Actually, she’s dead – Imagination’s Obituary.) We squelch imagination yet demand more innovation. That’s like trying to make ice cream without the milk.

No inspiration, no imagination – that’s a rule. Again, like innovation, imagination isn’t a thing in itself, it’s a result of something. If you’re not inspired you don’t have enough mojo to imagine what could be. I’ve seen many campaigns to increase innovation, but none to bolster imagination, and fewer to foster inspiration. (To be clear, motivation is not a substitute for inspiration – there are plenty of highly motivated, uninspired folks out there.)

If you want more innovation, it’s time to figure out how to make it cool to openly demonstrate imagination. (Here’s a hint – dust off your own imagination and use it. Others will see your public display and start to see it as sanctioned behavior.) And if you want more imagination, it’s time demonstrate random acts of inspiration.

Inspiration feeds imagination and imagination breeds innovation. And the sequence matters.

Image credit – AndYaDontStop

The Illusion of Planning

Planning is important work, but it’s non-value added work. Short and sweet – planning is waste.

Lean has taught us waste should be reduced, and the best way to reduce waste from planning is to spend less time planning. (I feel silly writing that.) Lean has taught us to reduce batch size, and the best way to reduce massive batch size of the annual planning marathon is to break it into smaller sessions. (I feel silly writing that too.)

Unreasonable time constraints increase creativity. To create next year’s plan, allocate just one for the whole thing. (Use a countdown timer.) And, because batch size must be reduced, repeat the process monthly. Twelve hours of the most productive planning ever, and countless planning hours converted into value added work.

Defining the future state and closing the gap is not the way to go. The way to go is to define the current state (where you are today) and define how to move forward. Use these two simple rules to guide you:

- Do more of what worked.

- Do less of what didn’t.

Here’s an example process:

The constraint – no new hires. (It’s most likely the case, so start there.)

Make a list of all the projects you’re working on. Decide which to stop right now (the STOP projects) and which you’ll finish by the end of the month (the COMPLETED projects). The remaining projects are the CONTINUE projects, and, since they’re aptly named, you should continue them next month. Then, count the number of STOP and COMPLETED projects – that’s the number of START projects you can start next month.

If the sum of STOP and COMPLETED is zero, ask if you can hire anyone this month. If the answer is no, see you next month.

If the sum is one, figure out what worked well, figure out how to build on it, and define the START project. Resources for the START project should be the same as the STOP or COMPLETED project.

If the sum is two, repeat.

Now ask if you can hire anyone this month. If the answer is no, you’re done. If the answer is yes, define how many you can hire.

With your number in hand, and building on what worked well, figure out the right START project. Resources must be limited by the number of new hires, and the project can’t start until the new hire is hired. (I feel silly writing that, but it must be written.) Or, if a START project can’t be started, use the new resource to pile on to an important CONTINUE project.

You’re done for the month, so send your updated plan to your boss and get back to work.

Next month, repeat.

The process will evolve nicely since you’ll refine it twelve times per year.

Ultimately, planning comes down to using your judgment to choose the next project based on the resources you’re given. The annual planning process is truly that simple, it’s just doesn’t look that way because it’s spread over so many months. So, if the company tells its leaders how many resources they have, and trusts them to use good judgment, yearly planning can be accomplished in twelve hours per year (literally). And since the plan is updated monthly, there’s no opportunity for emergency re-planning, and it will always be in line with reality.

Less waste and improved quality – isn’t that what lean taught us?

Summoning The Courage To Ask

I’ve had some great teachers in my life, and I’m grateful for them. They taught me their hard-earned secrets, their simple secrets. Though each had their own special gifts, they all gave them in the same way – they asked the simplest questions.

Today’s world is complex – everything interacts with everything else; and today’s pace is blistering – it’s tough to make time to understand what’s really going on. To battle the complexity and pace, force yourself to come up with the simplest questions. Here are some of my favorites:

For new products:

- Who will buy it?

- What must it do?

- What should it cost?

For new technologies:

- What problem are you trying to solve?

- How will you know you solved it?

- What work hasn’t been done before?

For new business models:

- Why are you holding onto your decrepit business model?

For problems:

- Can you draw a picture of it on one page?

- Can you make it come and go?

For decisions:

- What is the minimum viable test?

- Why not test three or four options at the same time?

For people issues:

- Are you okay?

- How can I help you?

For most any situation:

- Why?

These questions are powerful because they cut through the noise, but their power couples them to fear and embarrassment – fear that if you ask you’ll embarrass someone. These questions have the power to make it clear that all the activity and hype is nothing more than a big cloud of dust heading off in the wrong direction. And because of that, it’s scary to ask these questions.

It doesn’t matter if you steal these questions directly (you have my permission), twist them to make them your own, or come up with new ones altogether. What matters is you spend the time to make them simple and you summon the courage to ask.

Image credit — Montecruz Foto.

The Importance Of Knowing Why You’re In The Boat

Whether at work or home, there are highs and lows. And you’re not getting special treatment, that’s how it is for everyone. And it’s a powerful fundamental, so don’t try to control it, ride it.

When the sailing is smooth, at some point it won’t be – the winds change, that’s what they do. And when you’re suddenly buffeted from a new direction, you take action. But what action? More sail or less? Port or starboard? Heave the anchor or abandon ship? It depends.

Your actions depend on your why. Regardless of wind or tide, your why points where it points and guides your actions. Much like magnetic north doesn’t move if you spin your compass, your long term why knows where it points. If the storm on the horizon is dead ahead, you go around it. But it’s a balance – deviate to skirt the storm, but do it with your long term destination in mind. If you know your long term why, the best course heading is clear.

Often you set sail without realizing you don’t have your why battened down and stowed. When you sail where you sailed last time, you know the landmarks and use them to navigate. You can unknowingly leave your why at the pier and still get to your destination. But when you’re blown out to sea and can no longer see the landmarks, your moral compass, your long term why, is the only way to tack and jibe toward your destination.

Before you set sail, it’s best to know why you’re in the boat.

It Can’t Be Innovation If…

Companies strive for predictability, yet if it’s predictable, it cannot be innovation.

We seek comfort in our work, but if it’s comfortable it can’t be innovation.

Businesses like to grow by selling more to the customers we have, but if existing customers can recognize it, it can’t be innovation.

We want to meet year end numbers, but if the project will generate profit in the year it begins, it can’t be innovation.

We love our standardized processes, but if it’s standard, it cannot be innovation.

If there’s consensus, it’s not innovation.

If the project isn’t wreaking havoc with your organizational norms, it can’t be innovation.

If the market already exists, it can’t be innovation.

If you’ve done it before, it can’t be innovation.

If you are following a best practice, it can’t be innovation.

If there’s a high probability it will work, it can’t be innovation.

If people aren’t threatened, it can’t be innovation.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski