Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

You probably don’t have an organizational capability gap.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

The organizational capability of a company defines its ability to get things done. If you can’t pull it off, you have an organizational capability problem, or so the traditional thinking goes.

If you don’t have enough people to do the work, and the work is not new, that’s not a capability gap, that’s an organizational capacity gap. Capacity gaps are filled in straightforward ways. 1.) You can hire more people like the ones who do the work today and train them with the people you already have. Or for machines – buy more of the old machines you know and love. 2.) Map the work processes and design out the waste. Find the piles of paper or long queues and the bottleneck will be right in front. Figure out how to get more work through bottleneck. Professional tip – ignore everything but the bottleneck because fixing a non-bottleneck will only make you tired and sweaty and won’t increase throughput. 3.) Move people and machines from the work to create a larger shortfall. If no one complains, it wasn’t a problem and don’t fix it. If the complaints skyrocket, use the noise to justify the first or second option. And don’t let your ego get in the way – bigger teams aren’t better, they’re just bigger.

If your company systematically piles too work on everyone’s plate, you don’t have an organizational capability problem, you have a leadership problem.

If you’re asked to put together a future state organization and define its new capabilities, you don’t have an organizational capability gap. A capability gap exists only when there’s a business objective that must be satisfied, and a paper exercise to create a future state organization is not a business objective. Before starting the work, ask for the company’s growth objectives and an explanation of the new work your team will have to do to achieve those objectives. And ask how much money has been budgeted (and approved) for the future state organization and when you can make the first hire. This will reduce the urgency of the exercise, and may stop it altogether. And everyone will know there’s no “organizational capability gap.”

If you’re asked to put together a project plan (with timeline and budget) to create a new technology and present the plan to the CEO next week, you have an organizational capability gap. If there’s a shortfall in the company’s growth numbers and the VP of business development calls you at home and tells you to put together a plan to create a new market in a new country and present it to her tomorrow, you have an organizational capability gap. If the VP of sales takes you to a fancy restaurant and asks you to make a napkin sketch of your plan to sell the new product through a new channel, you have an organizational capability gap.

Real organizational capability gaps are rare. Unless there’s a change, there can be no organizational capability gap. There can be no gap without a new business deliverable, new technology, new partnership, new product, new market, or new channel. And without a timeline and an approved budget, I don’t know what you have, but you don’t have organizational capability gap.

Image credit – Jehane

Creating a brand that lasts.

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

One of the best ways to improve your brand is to improve your products. The most common way is to provide more goodness for less cost – think miles per gallon. Usually it’s a straightforward battle between market leaders, where one claims quantifiable benefit over the other – Ours gets 40 mpg and theirs doesn’t. And the numbers are tied to fully defined test protocols and testing agencies to bolster credibility. Here’s the data. Buy ours

But there’s a more powerful way to improve your brand, and that’s to map your products to reliability. It’s far a more difficult game than the quantified head-to-head comparison of fuel economy and it’s a longer play, but done right, it’s a lasting play that is difficult to beat. Run the thought experiment: think about the brands you associate with reliability. The brands that come to mind are strong, lasting brands, brands with staying power, brands whose products you want to buy, brands you don’t want to compete against. When you buy their products you know what you’re going to get. Your friends tell you stories about their products.

There’s a complete a complete tool set to create products that map to reliability, and they work. But to work them, the commercialization team has to have the right mindset. The team must have the patience to formally define how all the systems work and how they interact. (Sounds easy, but it can be painfully time consuming and the level of detail is excruciatingly extreme.) And they have to be willing to work through the discomfort or developing a common understanding how things actually work. (Sounds like this shouldn’t be an issue, but it is – at the start, everyone has a different idea on how the system works.) But more importantly, they’ve got to get over the natural tendency to blame the customer for using the product incorrectly and learn to design for unintended use.

The team has got to embrace the idea that the product must be designed for use in unpredictable ways in uncontrolled conditions. Where most teams want to narrow the inputs, this team designs for a wider range of inputs. Where it’s natural to tighten the inputs, this team designs the product to handle a broader set of inputs. Instead of assuming everything will work as intended, the team must assume things won’t work as intended (if at all) and redesign the product so it’s insensitive to things not going as planned. It’s strange, but the team has to design for hypothetical situations and potential problems. And more strangely, it’s not enough to design for potential problems the team knows about, they’ve got to design for potential problems they don’t know about. (That’s not a typo. The team must design for failure modes it doesn’t know about.)

How does a team design for failure modes it doesn’t know about? They build a computer-based behavioral model of the system, right down to the nuts, bolts and washers, and they create inputs that represent the environment around the system. They define what each element does and how it connects to the others in the system, capturing the governing physics and propagation paths of connections. Then they purposefully break the functions using various classes of failure types, run the analysis and review the potential causes. Or, in the reverse direction, the team perturbs the system’s elements with inputs and, as the inputs ripple through the design, they find previously unknown undesirable (harmful) functions.

Purposefully breaking the functions in known ways creates previously unknown potential failure causes. The physics-based characterization and the interconnection (interaction) of the system elements generate unpredicted potential failure causes that can be eliminated through design. In that way, the software model helps find potential failures the team did not know about. And, purposefully changing inputs to the system, again through the physics and interconnection of the elements, generates previously unknown harmful functions that can be designed out of the product.

If you care about the long-term staying power of your brand, you may want to take a look at TechScan, the software tool that makes all this possible.

Image credit — Chris Ford.

Finding Your Full Potential

If you’re all sad or anxious, you’re not operating at full potential.

If you’re all sad or anxious, you’re not operating at full potential.

If you’re sad, you’re thinking about the past. You’re remembering what happened and wishing it went differently. You’re compromising the present by spending emotional energy on something that cannot change. The past is gone, never to return. Can’t unwind it, can’t undo it. Let it go. Bring your mind back to your body. It’s time to realize your potential, and the only way to do that is to live in the present.

If you’re anxious or afraid, you’re thinking about the future. You’re thinking about what may happen and imagining that it’s not going to go your way. You’re practicing failure in the future. It’s not possible to control the future, so don’t try. And don’t worry about problems that haven’t happened yet because they may not happen at all. Grab your mind and reattach it to your body because the future is not made in the future, it’s made in the present. And that’s just where you’ll find your full potential.

You operate at your full potential when you apply your full attention to the present. In the present, all your internal resources are applied to the situation at hand. If you are in a conversation with a friend, you are fully engaged and practicing full-body listening. If you are working on a problem, each hemisphere sees it from its own perspective all-the-while discussing it with its better half. Point is, you’re all-in. Point is, all of you is in the present.

When you find your mind wandering in the past, take a breath and bring it back to the present so you can get back to living at your potential. When you find your mind worrying in the future, take two breaths and head back to the home of your full potential.

Whether you find it in the past or future, just bring your mind back to the present. There’s nothing wrong with a mind that wanders. Minds wander. That’s their nature. That’s what they do. Don’t be sad and don’t worry. Just bring it back.

Image credit – TEDxPioneerValley2012

Don’t mentor. Develop young talent.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent deserves your attention. But it’s not for the sake of the young talent, it’s for the survival of your company.

Your young talent understands technology far better than your senior leaders. And they don’t just know how it works, they know why people use it. And it’s not just social media. They know how to code, they know how to prototype (I think the call it hacking, or something like that.) and they know how things fit together. And they know what’s next. But they don’t know how to get things done within your organization.

Mentoring isn’t the right word. It’s a tired word without meaning, and we’ve demonstrated we care about it only from a compliance standpoint and not a content standpoint. The mentorship checklist – set up regular meetings, meet infrequently without an agenda, lie it die a slow death and then declare compliance. Nurturing is a better word, but it has connotations of taking care. Parenting captures the essence of the work, but it doesn’t fit with the language of companies. But that may not be so bad, because the work doesn’t fit with the operations companies.

In the short term it’s inefficient to spend precious leadership bandwidth on young talent, but in the long run, it’s the only way to go. Just as the yardwork goes more slowly when your kids help, the next time it’s a bit faster. But the real benefit, the unquantifiable benefit, is the pure joy of spending time with irreverent, energetic, idealistic young people. Yes, there’s less productivity (fewer leaves raked per hour), but that’s not what it’s about. There’s growth, increased capability and shared experience that will set up the next lesson.

The biggest mistake is to come up with special “mentorship projects”. Adding work for the sake of growing talent is wrong on so many levels. Instead, help them with the work they’re expected to do. Dig in. Help them. Contribute to their projects. Go to their meetings. Provide technical guidance. Look ahead for potential problems and tell them they are looming over the horizon. Let them make the decisions. Let them choose the path, but run ahead and make sure they negotiate the corner. If they’re going to make it, let them scoot through without them seeing you. If they’re going to crash, grab the wheel and negotiate the corner with them. Then, when things have calmed down, tell them why you stepped in.

Your children watch you. They watch how you interact with your spouse; they watch how you handle stressful situations; they watch how you treat other children; they listen to what you say to them; they listen to how you say it. And when the words disagree with the unsaid sentiment, they believe the sentiment. Your children know you by your actions. You are transparent to them. They know everything about you. They know why you do things and they know what you stand for. And young talent is no different.

There is nothing more invigorating than a bright, young person willing to dig in and make a difference. Their passion is priceless. And as much as you are helping them, they are helping you. They spark new thinking; they help you see the implicit assumptions you’ve left untested for too long and then naively stomp on them and give you a save-face way to revisit your old thinking. When the toddler learns to walk, even the grandparents spring to life and spryly support them step-by-step.

Don’t call it parenting, but behave like one. Take the time to form the close relationships that transcend the generational divide. Make it personal, because it is. And when you have too much to do and too little time to invest in young talent, do it anyway. Do it for them or do it for the company, but do it.

But in the end, do it for the right reason, the selfish reason – because it the best thing for you.

Image credit – mliu92

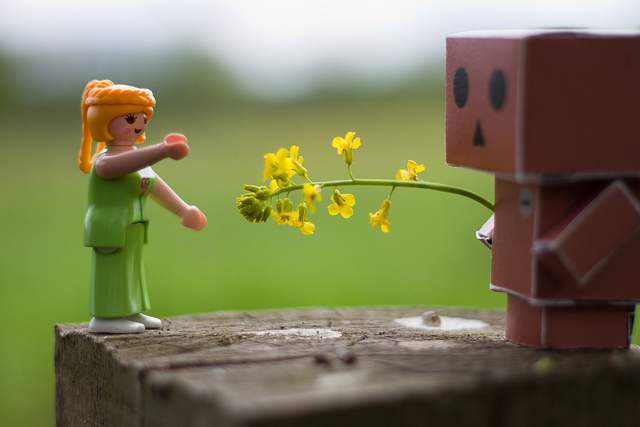

Scarcity and Abundance

Supply and demand have been joined at the hip since the beginning. When demand is high, the deck is shuffled so supply seems low. The fabricated scarcity drives up prices and shareholders are happy. When demand is low, the competition pushes each other on price. The abundance creates a commodity, and it’s a race to the bottom.

Supply and demand have been joined at the hip since the beginning. When demand is high, the deck is shuffled so supply seems low. The fabricated scarcity drives up prices and shareholders are happy. When demand is low, the competition pushes each other on price. The abundance creates a commodity, and it’s a race to the bottom.

But this is old thinking.

Scarcity isn’t a lever to jack up prices or manipulate relationships, it’s an opportunity to spend your limited resources on the most important work and to build relationships. When you tell a potential partner you want work with them and you are willing to spend your finite resources to make it happen, it’s a huge compliment. Voting with your feet makes a powerful statement that you’re serious about working with them because you think they’re special. You are telling them that you will say no to others so you can say yes to them. Both know they’re part of something important and the free-flowing positivity results in something otherwise impossible.

Scarcity is limiting only if your mental framework thinks it is. If you hoard and hold tightly, scarcity breeds win-lose relationships governed by power dynamics. But if you choose the anti-framework, scarcity creates trust.

Played differently, abundance does not create commodity, it’s opportunity to show others you have enough to spare. In personal relationships, when you share some of your work for free your relationships blossom. When you give it away you are signaling that you have plenty to spare. It’s clear to everyone you are a geyser of new thinking. Here – take this. I’ll make more. These simple words create a foundation of trust which bolsters your personal brand. And because all business relationships are personal relationships, it does the same thing for your company’s brand.

Make it a commodity or give it away – how you see abundance is your choice. The old way breeds bare-knuckled competition. The new way creates a brand steeped in trust.

If you have scarcity, be thankful for it. Allocate your precious resources thoughtfully and with love. Spend your time with the people and causes that matter. It will feel good to everyone, including you. And if you have abundance, be thankful. Choose to develop closer relationships based on trust. Choose to give it away.

Happy Thanksgiving.

image credit — GloriaGarcia

Put your success behind you.

The biggest blocker of company growth is your successful business model. And the more significant it’s historical success, the more it blocks.

Novelty meaningful to the customer is the life force of company growth. The easiest novelty to understand is novelty of product function. In a no-to-yes way, the old product couldn’t do it, but the new one can. And the amount of seconds it takes for the customer to notice (and in the case of meaningful novelty, appreciate) the novelty is in an indication of its significance. If it takes three months of using the product, rigorous data collection and a t-test, that’s not good. If the customer turns on the product and the novelty smashes him in the forehead like a sledgehammer, well, that’s better.

It’s difficult to create a product with meaningful novelty. Engineers know what they know, marketers know what they market, and the salesforce knows how to sell what they sell. And novelty cuts across their comfort. The technology is slightly different, the marketing message diverges a bit, and the sales argument must be modified. The novelty is driven by the product and the people respond accordingly. And, the new product builds on the old one so there’s familiarity.

Where injecting novelty into the product is a challenge, rubbing novelty on the business model provokes a level 5 pucker. Nothing has the stopping power of a proposed change to the business model. Novelty in the product is to novelty in the business model as lightning is to lightning bug – they share a word, but that’s it.

Novelty in the product is novelty of sheet metal, printed circuit boards and software. Novelty in the business model is novelty in how people do their work and novelty in personal relationships. Novelty in the product banal, novelty in the business model is personal.

No tools or best practices can loosen the pucker generated by novelty in the business model. The tired business model has been the backplane of success for longer than anyone can remember. The long-in-the-tooth model has worn deep ruts of success into the organization. Even the all-powerful Lean Startup methodology can’t save you.

The healing must start with an open discussion about the impermanence of all things, including the business model. The most enduring radioactive element has a half-life, and so does the venerable business model, even the most successful.

Where novelty in the product is technical, novelty in the business model is emotional. And that’s what makes it so powerful. Sprinkling the business model with novelty is scary at a deeply personal level – career jeopardy, mortgage insecurity and family volatility are primal drivers. But if you can push through, the rewards are magical.

Your business model has shaped you into an organization that’s optimized to do what it does. You can’t create new markets and sell to new products to new customers without changing your business model. Your business model may have been your secret sauce, but the world’s tastes have changed. It’s time to put your success behind you.

Image credit — MandaRose

The Chief Do-the-Right-Thing Officer – a new role to protect your brand.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Our unhealthy fascination with ever-increasing shareholder value has officially gone too far. In some companies dishonesty is now more culturally acceptable than missing the numbers. (Unless, of course, you get caught. Then, it’s time for apologies.) The sacrosanct mission statement can’t save us. Even the most noble can be stomped dead by the dirty boots of profitability.

Though, legally, companies can self-regulate, practically, they cannot. There’s nothing to balance the one-sided, hedonistic pursuit of profitability. What’s needed is a counterbalancing mechanism of equal and opposite force. What’s needed is a new role that is missing from today’s org chart and does not have a name.

Ombudsman isn’t the right word, but part of it is right – the part that investigates. But the tense is wrong – the ombudsman has after-the-fact responsibility. The ombudsman gets to work after the bad deed is done. And another weakness – ombudsman don’t have equal-and-opposite power of the C-suite profitability monsters. But most important, and what can be built on, is the independent nature of the ombudsman.

Maybe it’s a proactive ombudsman with authority on par with the Board of Directors. And maybe their independence should be similar to a Supreme Court justice. But that’s not enough. This role requires hulk-like strength to smash through the organizational obfuscation fueled by incentive compensation and x-ray vision to see through the magical cloaking power of financial shenanigans. But there’s more. The role requires a deep understanding of complex adaptive systems (people systems), technology, patents and regulatory compliance; the nose of an experienced bloodhound to sniff out the foul; and the jaws of a pit bull that clamp down and don’t let go.

Ombudsman is more wrong than right. I think liability is better. Liability, as a word, has teeth. It sounds like it could jeopardize profitability, which gives it importance. And everyone knows liability is supposed to be avoided, so they’d expect the work to be proactive. And since liability can mean just about anything, it could provide the much needed latitude to follow the scent wherever it takes. Chief Liability Officer (CLO) has a nice ring to it.

[The Chief Do-The-Right-Thing Officer is probably the best name, but its acronym is too long.]

But the Chief Liability Officer (CLO) must be different than the Chief Innovation Officer (CIO), who has all the responsibility to do innovation with none of the authority to get it done. The CLO must have a gavel as loud as the Chief Justice’s, but the CLO does not wear the glasses of a lawyer. The CLO wears the saffron robes of morality and ethics.

Is Chief Liability Officer the right name? I don’t know. Does the CLO report to the CEO or the Board of Directors? Don’t know. How does the CLO become a natural part of how we do business? I don’t know that either.

But what I do know, it’s time to have those discussions.

Image credit – Dietmar Temps

Solving Intractable Problems

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Immediately after there’s an elegant solution to a previously intractable problem, the solution is obvious to others. But, just before the solution those same folks said it was impossible to solve. I don’t know if there’s a name for this phenomenon, but it certainly causes hart burn for those brave enough to take on the toughest problems.

Intractable problems are so fundamental they are no longer seen as problems. Over the years experts simply accept these problems as constraints that must be complied with. Just as the laws of physics can’t be broken, experts behave as if these self-made constraints are iron-clad and believe these self-build walls define the viable design space. To experts, there is only viable design space or bust.

A long time ago these problems were intractable, but now they are not. Today there are new materials, new analysis techniques, new understanding of physics, new measurement systems and new business models.. But, they won’t be solved. When problems go unchallenged and constrain design space they weave themselves into the fabric of how things are done and they disappear. No one will solve them until they are seen for what they are.

It takes time to slow down and look deeply at what’s really going on. But, today’s frantic pace, unnatural fascination with productivity and confusion of activity with progress make it almost impossible to slow down enough to see things as they are. It takes a calm, centered person to spot a fundamental problem masquerading as standard work and best practice. And once seen for what they are it takes a courageous person to call things as they are. It’s a steep emotional battle to convince others their butts have been wet all these years because they’ve been sitting in a mud puddle.

Once they see the mud puddle for what it is, they must then believe it’s actually possible to stand up and walk out of the puddle toward previously non-viable design space where there are dry towels and a change of clothes. But when your butt has always been wet, it’s difficult to imagine having a dry one.

It’s difficult to slow down to see things as they are and it’s difficult to re-map the territory. But it’s important. As continuous improvement reaches the limit of diminishing returns, there are no other options. It’s time to solve the intractable problems.

Image credit – Steven Depolo

Out of Context

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

“It’s a fact.” is a powerful statement. It’s far stronger than a simple description of what happened. It doesn’t stop at describing a sequence of events that occurred in the past, rather it tacks on an implication of what to think about those events. When “it’s a fact” there’s objective evidence to justify one way of thinking over another. No one can deny what happened, no one can deny there’s only one way to see things and no one can deny there’s only one way to think. When it’s a fact, it’s indisputable.

Facts aren’t indisputable, they’re contextual. Even when an event happens right in front of two people, they don’t see it the same way. There are actually two events that occurred – one for each viewer. Two viewers, two viewing angles, two contexts, two facts. Right at the birth of the event there are multiple interpretations of what happened. Everyone has their own indisputable fact, and then, as time passes, the indisputables diverge.

On their own there’s no problem with multiple diverging paths of indisputable facts. The problem arises when we use indisputable facts of the past to predict the future. Cause and effect are not transferrable from one context to another, even if based on indisputable facts. The physics of the past (in the true sense of physics) are the same as the physics of today, but the emotional, political, organizational and cultural physics are different. And these differences make for different contexts. When the governing dynamics of the past are assumed to be applicable today, it’s easy to assume the indisputable facts of today are the same as yesterday. Our static view of the world is the underlying problem, and it’s an invisible problem.

We don’t naturally question if the context is different. Mostly, we assume contexts are the same and mostly we’re blind to those assumptions. What if we went the other way and assumed contexts are always different? What would it feel like to live in a culture that always questions the context around the facts? Maybe it would be healthy to justify why the learning from one situation applies to another.

As the pace of change accelerates, it’s more likely today’s context is different and yesterday’s no longer applies. Whether we want to or not, we’ll have to get better at letting go of indisputable facts. Instead of assuming things are the same, it’s time to look for what’s different.

Image credit — Joris Leermakers

Don’t worry about the words, worry about the work.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Doing anything for the first time is difficult. It goes with the territory. Instead of seeing the associated anxiety as unwanted and unpleasant, maybe you can use it as an indicator of importance. In that way, if you don’t feel anxious you know you’re doing what you’ve done before.

Innovation, as a word, has been over used (and misused). Some have used the word to repackage the same old thing and make it fresh again, but more commonly people doing good work attach the word innovation to their work when it’s not. Just because you improved something doesn’t mean it’s innovation. This is the confusion made by the lean and Six Sigma movements – continuous improvement is not innovation. The trouble with saying that out loud is people feel the distinction diminishes the importance of continuous improvement. Continuous improvement is no less important than innovation, and no more. You need them both – like shoes and socks. But problems arise when continuous improvement is done in the name of innovation and innovation is done at the expense of continuous improvement – in both cases it’s shoes, no socks.

Coming up with an acid test for innovation is challenging. Innovation is a know-it-when-you-see-it thing that’s difficult to describe in clear language. It’s situational, contextual and there’s no prescription. [One big failure mode with innovation is copying someone else’s best practice. With innovation, cutting and pasting one company’s recipe into another company’s context does not work.] But prescriptions and recipes aside, it can be important to know when it’s innovation and when it isn’t.

If the work creates the foundation that secures your company’s growth goals, don’t worry about what to call it, just do it. If that work doesn’t require something radically new and different, all-the-better. But you likely set growth goals that were achievable regardless of the work you did. But still, there’s no need to get hung up on the label you attach to the work. If the work helps you sell to customers you could not sell to before, call it what you will, but do more of it. If the work creates a whole new market, what you call it does not matter. Just hurry up and do it again.

If your CEO is worried about the long term survivability of your company, don’t fuss over labelling your work with the right word, do something different. If you have to lower your price to compete, don’t assign another name to the work, do different work. If your new product is the same as your old product, don’t argue if it’s the result of continuous improvement or discontinuous improvement. Just do something different next time.

Labelling your work with the right word is not the most important thing. It’s far more important to ask yourself – Five years from now, if the company is offering a similar product to a similar set of customers, what will it be like to work at the company? Said another way, arguing about who is doing innovation and who is not gets in the way of doing the work needed to keep the company solvent.

If the work scares you, that’s a good indication it’s meaningful. And meaningful is good. If it scares you because it may not work, you’re definitely trying something new. And that’s good. But it’s even better if the work scares you because it just might come to be. If that’s the case, your body recognizes the work could dismantle a foundational element of your business – it either invalidates your business model or displaces a fundamental technology. Regardless of the specifics, anxiety is a good surrogate for importance.

In some cases, it can be important what you call the work. But far more important than getting the name right is doing the right work. If you want to argue about something, argue if the work is meaningful. And once a decision is reached, act accordingly. And if you want to have a debate, debate the importance of the work, then do the important work as fast as you can.

Do the important work at the expense of arguing about the words.

It’s time to make a difference.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

If on the first day on your new job your stomach is all twisted up with anxiety and you’re second guessing yourself because you think you took a job that is too big for you, congratulations. You got it right. The right job is supposed to feel that way. If on your first day you’re totally comfortable because you’ve done it all before and you know how it will go, you took the job for the money. And that’s a terrible reason to take a job.

You got the job because someone who knew what it would take to get it done believed you were the right one to do just that. This wasn’t charity. There was something in it for them. They needed the job done and they wanted a pro. And they chose you. The fact their stomach isn’t in knots says nothing about their stomach and everything about their belief in you. And the knots in your stomach? That ‘s likely a combination of immense desire to do a good job and an on-the-low-side belief in yourself.

If we’re not stretching we’re not learning, and if we’re not learning we’re not living. So why the nerves? Why the self doubt? Why don’t we believe in ourselves? When we look inside, we see ourselves in the moment – in the now, as we are. And sometimes when we look inside there are only re-run stories of our younger selves. It’s difficult to see our future selves, to see our own growth trajectory from the inside. It’s far easier to see a growth trajectory from the outside. And that’s what the hiring team sees – our future selves – and that’s why they hire.

This growth-stretch, anxiety-doubt seesaw is not unique to new jobs. It’s applicable right down the line – from temporary assignments, big projects and big tasks down to small tasks with tight deliverables. If you haven’t done it before, it’s natural to question your capability. But if you trust the person offering the job, it should be natural to trust their belief in you.

When you sit in your new chair for the first time and you feel queasy, that’s not a sign of incompetence it’s a sign of significance. And it’s a sign you have an opportunity to make a difference. Believe in the person that hired you, but more importantly, believe in yourself. And go make a difference.

Image credit – Thomas Angermann

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski