Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

Is your tank empty?

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

Sometimes your energy level runs low. That’s not a bad thing, it’s just how things go. Just like a car’s gas tank runs low, our gas tanks, both physical and emotional, also need filling. Again, not a bad thing. That’s what gas tanks are for – they hold the fuel.

We’re pretty good at remembering that a car’s tank is finite. At the start of the morning commute, the car’s fuel gauge gives a clear reading of the fuel level and we do the calculation to determine if we can make it or we need to stop for fuel. And we do the same thing in the evening – look at the gauge, determine if we need fuel and act accordingly. Rarely we run the car out of fuel because the car continuously monitors and displays the fuel level and we know there are consequences if we run out of fuel.

We’re not so good at remembering our personal tanks are finite. At the start of the day, there are no objective fuel gauges to display our internal fuel levels. The only calculation we make – if we can make it out of bed we have enough fuel for the day. We need to do better than that.

Our bodies do have fuel gages of sorts. When our fuel is low we can be irritable, we can have poor concentration, we can be easily distracted. Though these gages are challenging to see and difficult to interpret, they can be used effectively if we slow down and be in our bodies. The most troubling part has nothing to do with our internal fuel gages. Most troubling is we fail to respect their low fuel warnings even when we do recognize them. It’s like we don’t acknowledge our tanks are finite.

We don’t think our cars are flawed because their fuel tanks run low as we drive. Yet, we see the finite nature of our internal fuel tanks as a sign of weakness. Why is that? Rationally, we know all fuel tanks are finite and their fuel level drops with activity. But, in the moment, when are tanks are low, we think something is wrong with us, we think we’re not whole, we think less of ourselves.

When your tank is low, don’t curse, don’t blame, don’t feel sorry and don’t judge. It’s okay. That’s what tanks do.

A simple rule for all empty tanks – put fuel in them.

Image credit – Hamed Saber

The Slow No

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

When there’s too much to do and too few to do it, the natural state of the system is fuller than full. And in today’s world we run all our systems this way, including our people systems.

A funny thing happens when people’s plates are full – when a new task is added an existing one hits the floor. This isn’t negligence, it’s not the result of a bad attitude and it’s not about being a team player. This is an inherent property of full plates – they cannot support a new task without another sliding off. And drinking glasses have this same interesting property – when full, adding more water just gets the floor wet.

But for some reason we think people are different. We think we can add tasks without asking about free capacity and still expect the tasks to get done. What’s even more strange – when our people tell us they cannot get the work done because they already have too much, we don’t behave like we believe them. We say things like “Can you do more things in parallel?” and “Projects have natural slow phases, maybe you can do this new project during the slow times.” Let’s be clear with each other – we’re all overloaded, there are no slow times.

For a long time now, we’ve told people we don’t want to hear no. And now, they no longer tell us. They still know they can’t get the work done, but they know not to use the word “no.” And that’s why the Slow No was invented.

The Slow No is when we put a new project on the three year road map knowing full-well we’ll never get to it. It’s not a no right now, it’s a no three years from now. It’s elegant in its simplicity. We’ll put it on the list; we’ll put it in the queue; we’ll put it on the road map. The trick is to follow normal practices to avoid raising concerns or drawing attention. The key to the Slow No is to use our existing planning mechanisms in perfectly acceptable ways.

There’s a big downside to the Slow No – it helps us think we’ve got things under control when we don’t. We see a full hopper of ideas and think our future products will have sizzle. We see a full road map and think we’re going to have a huge competitive advantage over our competitors. In both situations, we feel good and in both situations, we shouldn’t. And that’s the problem. The Slow No helps us see things as we want them and blocks us from seeing them as they are.

The Slow No is bad for business, and we should do everything we can to get rid of it. But, it’s engrained behavior and will be with us for the near future. We need some tools to battle the dark art of the Slow No.

The Slow No gives too much value to projects that are on the list but inactive. We’ve got to elevate the importance of active, fully-staffed projects and devalue all inactive projects. Think – no partial credit. If a project is active and fully-staffed, it gets full credit. If it’s inactive (on a list, in the queue, or on the road map) it gets zero credit. None. As a project, it does not exist.

To see things as they are, make a list of the active, fully-staffed projects. Look at the list and feel what you feel, but these are the only projects that matter. And for the road map, don’t bother with it. Instead, think about how to finish the projects you have. And when you finish one, start a new one.

The most difficult element of the approach is the valuation of active but partially-staffed projects. To break the vice grip of the Slow No, think no partial credit. The project is either fully-staffed or it isn’t And if it’s not fully-staffed, give the project zero value. None. I know this sounds outlandish, but the partially-staffed project is the slippery slope that gives the Slow No its power.

For every fully-staffed project on your list, define the next project you’ll start once the current one is finished. Three active projects, three next projects. That’s it. If you feel the need to create a road map, go for it. Then, for each active project, use the road map to choose the next projects. Again, three active projects, three next projects. And, once the next projects are selected, there’s no need to look at the road map until the next projects are almost complete.

The only projects that truly matter are the ones you are working on.

Image credit – DaPuglet

Being Right in the Right Way

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

When something doesn’t feel right, respect your intuition. Even when you don’t know why it doesn’t feel right, respect your gut. When something doesn’t make sense, don’t judge yourself negatively. Rather, make the commitment to dig deeply until you hit the fundamentals. When a proposed approach violates something inside, don’t be afraid to say what you think is right. Or, be afraid and say it anyway. But right doesn’t mean your predictions will come true. Right means you thought about it, you understand things differently and you have a coherent rationale for thinking as you do. And right also means you don’t understand, but you want to. And right means something does not sit well with you and you don’t know why. And it means the right view is important to you.

Right doesn’t mean correct. And right doesn’t mean something else is wrong. When you have right view, it doesn’t mean you see things exactly right. It means you’re going about things in a way that’s right for the situation. It means your approach feels right to the people involved. It means you’re going about things with the right intention.

Now, like with any new idea, you’re obligated to formalize what you think is right and explain it to your peers. But, to be clear, you’re not looking for permission, you’re writing it down to help you understand what you think. When you try to present your thoughts, you’ll learn what you know and what you don’t. You’ll learn which words work and which don’t. You’ll learn right speech.

And you’ll find the potholes. And that’s why you present to your peers. They’ll be critical of the idea and respectful of you. They’ll tell you the truth because they know it’s better to iron out the details early and often. As a group, you’ll support each other. As a group, you’ll take the right action.

When ideas are introduced that are different, the organization will feel stress. Everyone wants to do a good job, yet there’s no agreement on the right way. Even though there’s stress, no one wants to create harm and everyone wants to behave ethically. It’s important to demonstrate compassion to yourself and others. The stress is natural, but it’s also natural to go about your livelihood in the right way.

But when the stakes are high and there’s no consensus on how to move forward, it’s not easy to hold onto the right mental state. The stress can cause us to delude ourselves into thinking things aren’t going well. But, letting the disagreement go unaddressed is unskillful, as it will only fester. It’s far more skillful to respectfully debate and discuss the disagreement. In that way, everyone makes the right effort to work things out.

Over time, the pattern of behavior can transition to a natural openness where ideas are shared freely. This becomes easier when we drop the mental habit of categorizing things into buckets we like and buckets we don’t. And it helps to maintain awareness of how things really are so we can strip away our subjective options. In this case, mindfulness is the right way to go.

None of this is easy. Our minds are constantly distracted by competing demands, growing to-do lists and organizational complexities of the work. Without dedicated practice, our minds can get lost in a flurry of thoughts of our own creation. To make it work, we’ve got to maintain a heightened alertness to our mental state and that takes the right concentration.

There’s nothing new here, but this well-worn path has merit.

Image credit – saamiblog

How to Choose the Best Idea

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

We have too many ideas, but too few great ones. We don’t need more ideas, we need a way to choose the best one or two ideas and run them to ground.

Before creating more ideas, make a list of the ones you already have. Put them in two boxes. In Box 1, list the ideas without a video of a functional prototype in action. In Box 2, list the ideas that have a video showing a functional prototype demonstrating the idea in action. For those ideas with a functional prototype and no video, put them in Box 1.

Next, throw away Box 1. If it’s not important enough to make a crude physical prototype and create a simple video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If someone isn’t willing to carve out the time to make a physical prototype, there’s no emotional energy behind the idea and it should be left to die. And when people complain that it’s unfair to throw away all those good ideas in Box 1, tell them it’s unfair to spend valuable resources talking about ideas that aren’t worthy. And suggest, if they want to have a discussion about an idea, they should build a physical prototype and send you the video. Box 2, or bust.

Next, get the band together and watch the short videos in Box 2, and, as a group, put them in two boxes. In Box 3, put the videos without customers actively using the functional prototype. In Box 4, put the videos with customers actively using the functional prototype.

Next, throw way Box 3. If it’s not important enough to make a trip to an important customer and create a short video, the idea isn’t worth a damn. If you’re not willing to put yourself out there and take the idea to an important customer, the idea is all fizzle and no sizzle. Meaningful ideas take immense personal energy to run through the gauntlet, and without a video of a customer using the functional prototype, there’s not enough energy behind it. And when everyone argues that Box 3 ideas are worth pursuing, tell them to pursue a video showing a most important customer demonstrating the functional prototype.

Next, get the band back together to watch the Box 4 videos. Again, put the videos in two boxes. In Box 5 put the videos where the customer didn’t say what they liked and how they’d use it. In Box 6, put the videos where the customer enthusiastically said what they liked and how they’ll use it.

Next, throw away Box 5. If the customer doesn’t think enough about the prototype to tell you how they’ll use it, it’s because they don’t think much of the idea. And when the group says the customer is wrong or the customer doesn’t understand what the prototype is all about, suggest they create a video where a customer enthusiastically explains how they’d use it.

Next, get the band back in the room and watch the Box 6 videos. Put them in two boxes. In Box 7, put the videos that won’t radically grow the top line. In Box 8, put the videos that will radically grow the top line. Throw away Box 7.

For the videos in Box 8, rank them by the amount of top line growth they will create. Put all the videos back into Box 8, except the video that will create the most top line growth. Do NOT throw away Box 8.

The video in your hand IS your company’s best idea. Immediately charter a project to commercialize the idea. Staff it fully. Add resources until adding resources doesn’t no longer pulls in the launch. Only after the project is fully staffed do you put your hand back into Box 8 to select the next best idea.

Continually evaluate Boxes 1 through 8. Continually throw out the boxes without the right videos. Continually choose the best idea from Box 8. And continually staff the projects fully, or don’t start them.

Image credit – joiseyshowaa

What’s your problem?

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

If you don’t have a problem, you’ve got a big problem.

It’s important to know where a problem happens, but also when it happens.

Solutions are 90% defining and the other half is solving.

To solve a problem, you’ve got to understand things as they are.

Before you start solving a new problem, solve the one you have now.

It’s good to solve your problems, but it’s better to solve you customers’ problems.

Opportunities are problems in sheep’s clothing.

There’s nothing worse than solving the wrong problem – all the cost with none of the solution.

When you’re stumped by a problem, make it worse then do the opposite.

With problem definition, error on the side of clarity.

All problems are business problems, unless you care about society’s problems.

Odds are, your problem has been solved by someone else. Your real problem is to find them.

Define your problem as narrowly as possible, but no narrower.

Problems are not a sign of weakness.

Before adding something to solve the problem, try removing something.

If your problem involves more than two things, you have more than one problem.

The problem you think you have is never the problem you actually have.

Problems can be solved before, during or after they happen and the solutions are different.

Start with the biggest problem, otherwise you’re only getting ready to solve the biggest problem.

If you can’t draw a closeup sketch of the problem, you don’t understand it well enough.

If you have an itchy backside and you scratch you head, you still have an itch. And it’s the same with problems.

If innovation is all about problem solving and problem solving is all about problem definition, well, there you have it.

Image credit – peasap

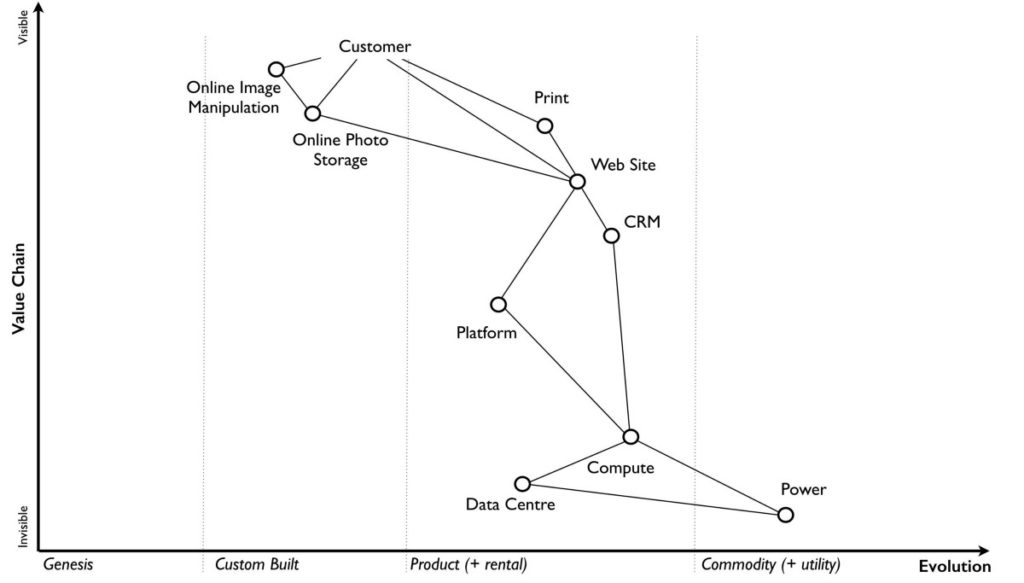

Mapping the Future with Wardley Maps

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

How do you know when it’s time to reinvent your product, service or business model? If you add ten units of energy and you get less in return than last time, it’s time to work in new design space. If improvement in customer goodness (e.g., miles per gallon in a car) has slowed or stopped, it’s time to seek a new fuel source. If recent patent filings are trivial enhancements that can be measured only with a large sample sizes and statistical analysis, the party is over.

When there’s so many new things to work on, how do you choose the next project? When you’re lost, you look at a map. And when there is no map, you make one. The first bit of work is defined by the holes in the first revision of your map. And once the holes are filled and patched, the next work emerges from the map itself. And, in a self-similar way, the next work continually emerges from the previous work until the project finishes.

But with so much new territory, how do you choose the right new territory to map? You don’t. Before there’s a need to map new territory, you must map the current territory. What you’ll learn is there are immature areas that, when made mature, will deliver new value to customers. And you’ll also learn the mature areas that must be blown up and replaced with infant solutions that will ultimately create the next evolution of your business. And as you run thought experiments on your map – projecting advancements on the various elements – the right new territory will emerge. And here’s a hint – the right new solutions will be enabled by the newly matured elements of the map.

But how do you predict where the right new solutions will emerge? I can’t tell you that. You are the experts, not me. All I can say is, make the maps and you’ll know.

And when I say maps, I mean Wardely Maps – here’s a short video (go to 4:13 for the juicy bits).

Image credit – Simon Wardley

It’s time to stretch yourself.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

If the work doesn’t stretch you, choose new work. Don’t go overboard and make all your work stretch you and don’t choose work that will break you. There’s a balance point somewhere between 0% and 100% stretch and that balance point is different for everyone and it changes over time. Point is, seek your balance point.

To find the right balance point, start with an assessment of your stretch level. List the number of projects you have and sum the number of major deliverables you’ve got to deliver. If you have more than three projects, you have too many. And if you think you take on more than three because you’re superhuman, you’re wrong. The data is clear – multitasking is a fallacy. If you have four projects you have too many. And it’s the same with three, but you’d think I was crazy if I suggested you limit your projects to two. The right balance point starts with reducing the number of projects you work on.

Now that you eliminated four or five projects and narrowed the portfolio down to the vital two or three, it’s time to list your major deliverables. Take a piece of paper and write them in a column down the left side of the page. And in a column next to the projects, categorize each of them as: -1 (done it before), 0 (done something similar), 1 (new to me), 2 (new to team), 3 (new to company), 5 (new to industry), 11 (new to world).

For the -1s, teach an entry level person how to do it and make sure they do it well. For the 0s, find someone who deserves a growth opportunity and let them have the work. And check in with them to make sure they do a good job. The idea is to free yourself for the stretch work.

For the 1s, find the best person in the team who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, do as they suggest but build on their work and take it to the next level.

For the 2s, find the best person in the company who has done it before and ask them how to do it. Then, build on their approach and make it your own.

For the 3s, do your research and find out who in your industry has done it before. Figure out how they did it and improve on their work.

For the 5s, do your research and figure out who has done similar work in another industry. Adapt their work to your application and twist it into something magical.

And for the 11s, they’re a special project category that live in rarified air and deserve a separate blog post of their own.

Start with where you are – evaluate your existing deliverables, cull them to a reasonable workload and assess your level of stretch. And, where it makes sense, stop doing work you’ve done before and start doing work you haven’t done yet. Stretch yourself, but be reasonable. It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Image credit – filtran

Starting 101

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

Doing challenging work isn’t difficult. Starting challenging work is difficult.

The downside of making a mistake is far less than the downside of not starting.

If you know how it will turn out, you waited too long to start.

Stopping is fine, as long as it’s followed closely by starting.

The scope of the project you start is defined by the cash in your pocket.

If you don’t start you can’t learn.

The project doesn’t have to be all figured out before starting, you just have to start.

Starting is scary because it’s important.

Before you can start you’ve got to decide to start.

If you’re finally ready to start, you should have started yesterday.

Without starting there can be no finishing.

Starting is blocked by both the fear of success and the fear of failure.

You don’t need to be ready to start, you just need to start.

The only thing in the way of starting is you.

Image credit — Dermot O’Halloran

A Barometer for Uncertainty

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Novelty, or newness, can be a great way to assess the status of things. The level of novelty is a barometer for the level of uncertainty and unpredictability. If you haven’t done it before, it’s novel and you should expect the work to be uncertain and unpredictable. If you’ve done it before, it’s not novel and you should expect the work to go as it did last time. But like the barometer that measures a range of atmospheric pressures and gives an indication of the weather over the next hours, novelty ranges from high to low in small increments and so does the associated weather conditions.

Barometers have a standard scale that measures pressure. When the summer air is clear and there are no clouds, the atmospheric pressure is high and on the rise and you should put on sun screen. When it’s hurricane season and super-low system approaches, the drops to the floor and you should evacuate. The nice thing about barometers is they are objective. On all continents, they can objectively measure the pressure and display it. No judgement, just read the scale. And regardless of the level of pressure and the number of times they measure it, the needle matches the pressure. No Kentucky windage. But novelty isn’t like that.

The only way to predict how things will go based on the level of novelty is to use judgement. There is no universal scale for novelty that works on all projects and all continents. Evaluating the level of novelty and predicting how the projects will go requires good judgement. And the only way to develop good judgment is to use bad judgment until it gets better.

All novelty isn’t created equal. And that’s the trouble. Some novelty has a big impact on the weather and some doesn’t. The trick is to know the difference. And how to tell the difference? If when you make a change in one part of the system (add novelty) and the novelty causes a big change in the function or operation of the system, that novelty is important. The system is telling you to use a light hand on the tiller. If the novelty doesn’t make much difference in system performance, drive on. The trick is to test early and often – simple tests that give thumbs-up or thumbs-down results. And if you try to run a test and you can’t get the test to run at all, there’s a hurricane is on the horizon.

When the work is new, you don’t really know which novelty will bite you. But there’s one rule: all novelty will bite you until proven otherwise. Make a list of the novel elements of the and test them crudely and quickly.

Make It Easy

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

When you push, you make it easy for people resist. When you break trail, you make it easy for them to follow.

Efficiency is overrated, especially when it interferes with effectiveness. Make it easy for effectiveness to carry the day.

You can push people off a cliff or build them a bridge to the other side. Hint – the bridge makes it easy.

Even new work is easy when people have their own reasons for doing it.

Making things easier is not easy.

Don’t tell people what to do. Make it easy for them to use their good judgement.

Set the wrong causes and conditions and creativity screeches to a halt. Set the right ones and it flows easily. Creativity is a result.

Don’t demand that people pull harder, make it easier for them to pull in the same direction.

Activity is easy to demonstrate and progress isn’t. Figure out how to make progress easier to demonstrate.

The only way to make things easier is to try to make them easier.

Image credit – Richard Hurd

To improve productivity, it’s time to set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

The race for productivity is on. And to take productivity to the next level, set limits.

To reduce the time wasted by email, limit the number of emails a person can send to ten emails per day. Also, eliminate the cc function. If you send a single email to ten people, you’re done for the day. This will radically reduce the time spent writing emails and reduce distraction as fewer emails will arrive. But most importantly, it will help people figure out which information is most important to communicate and create a natural distillation of information. Lastly, limit the number of word in an email to 100. This will shorten the amount of time to read emails and further increase the density of communications.

If that doesn’t eliminate enough waste, limit the number of emails a person can read to ten emails per day. Provide the subject of the email and the sender, but no preview. Use the subject and sender to decide which emails to read. And, yes, responding to an email counts against your daily sending quota of ten. The result is further distillation of communication. People will take more time to decide which emails to read, but they’ll become more productive through use of their good judgement.

Limit the number of meetings people can attend to two per day and cap the maximum meeting length to 30 minutes. The attendees can use the meeting agenda, meeting deliverables and decisions made at the meeting to decide which meetings to attend. This will cause the meeting organizers to write tight, compelling agendas and make decisions at meetings. Wasteful meetings will go away and productivity will increase.

To reduce waiting, limit the number of projects a person can work on to a single project. Set the limit to one. That will force people to chase the information they need instead of waiting. And if they can’t get what they need, they must wait. But they must wait conspicuously so it’s clear to leaders that their people don’t have what they need to get the project done. The conspicuous waiting will help the leaders recognize the problem and take action. There’s a huge productivity gain by preventing people from working on things just to look busy.

Though harsh, these limits won’t break the system. But they will have a magical influence on productivity. I’m not sure ten is the right number of emails or two is the right number of meetings, but you get the idea – set limits. And it’s certainly possible to code these limits into your email system and meeting planning system.

Not only will productivity improve, happiness will improve because people will waste less time and get to use their judgement.

Everyone knows the systems are broken. Why not give people the limits they need and make the productivity improvements they crave?

Image credit – XoMEoX

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski