Archive for the ‘Fundementals’ Category

Want to succeed? Learn how to deliver customer value.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whatever your initiative, start with customer value. Whatever your project, base it on customer value. And whatever your new technology, you guessed it, customer value should be front and center.

Whenever the discussion turns to customer value, expect confusion, disagreement, and, likely, anger. To help things move forward, here’s an operational definition I’ve found helpful:

When they buy it for more than your cost to make it, you have customer value.

And when there’s no way to pull out of the death spiral of disagreement, use this operational definition to avoid (or stop) bad projects:

When no one will buy it, you don’t have customer value and it’s a bad project.

As two words, customer and value don’t seem all that special. But, when you put them together, they become words to live by. But, also, when you do put them together, things get complicated. Here’s why.

To provide customer value, you’ve got to know (and name) the customer. When you asked “Who is the customer?” the wheels fall off. Here are some wrong answers to that tricky question. The Board of Directors is the customer. The shareholders are the customers. The distributor is the customer. The OEM that integrates your product is the customer. And the people that use the product are the customer. Here’s an operational definition that will set you free:

When someone buys it, they are the customer.

When the discussions get sticky, hold onto that definition. Others will try to bait you into thinking differently, but don’t bite. It will be difficult to stand your ground. And if you feel the group is headed in the wrong direction, try to set things right with this operational definition:

When you’ve found the person who opens their wallet, you’ve found the customer.

Now, let’s talk about value. Isn’t value subjective? Yes, it is. And the only opinion that matters is the customer’s. And here’s an operational definition to help you create customer value:

When you solve an important customer problem, they find it valuable.

And there you have it. Putting it all together, here’s the recipe for customer value:

- Understand who will buy it.

- Understand their work and identify their biggest problem.

- Solve their problem and embed it in your offering.

- Sell it for more than it costs you to make it.

Image credit — Caroline

The Most Important People in Your Company

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

When the fate of your company rests on a single project, who are the three people you’d tap to drag that pivotal project over the finish line? And to sharpen it further, ask yourself “Who do I want to lead the project that will save the company?” You now have a list of the three most important people in your company. Or, if you answered the second question, you now have the name of the most important person in your company.

The most important person in your company is the person that drags the most important projects over the finish line. Full stop.

When the project is on the line, the CEO doesn’t matter; the General Manager doesn’t matter; the Business Leader doesn’t matter. The person that matters most is the Project Manager. And the second and third most important people are the two people that the Project Manager relies on.

Don’t believe that? Well, take a bite of this. If the project fails, the product doesn’t sell. And if the product doesn’t sell, the revenue doesn’t come. And if the revenue doesn’t come, it’s game over. Regardless of how hard the CEO pulls, the product doesn’t launch, the revenue doesn’t come, and the company dies. Regardless of how angry the GM gets, without a product launch, there’s no revenue, and it’s lights out. And regardless of the Business Leader’s cajoling, the project doesn’t cross the finish line unless the Project Manager makes it happen.

The CEO can’t launch the product. The GM can’t launch the product. The Business Leader can’t launch the product. Stop for a minute and let that sink in. Now, go back to those three sentences and read them out loud. No, really, read them out loud. I’ll wait.

When the wheels fall off a project, the CEO can’t put them back on. Only a special Project Manager can do that.

There are tools for project management, there are degrees in project management, and there are certifications for project management. But all that is meaningless because project management is alchemy.

Degrees don’t matter. What matters is that you’ve taken over a poorly run project, turned it on its head, and dragged it across the line. What matters is you’ve run a project that was poorly defined, poorly staffed, and poorly funded and brought it home kicking and screaming. What matters is you’ve landed a project successfully when two of three engines were on fire. (Belly landings count.) What matters is that you vehemently dismiss the continuous improvement community on the grounds there can be no best practice for a project that creates something that’s new to the world. What matters is that you can feel the critical path in your chest. What matters is that you’ve sprinted toward the scariest projects and people followed you. And what matters most is they’ll follow you again.

Project Managers have won the hearts and minds of the project team.

The Project manager knows what the team needs and provides it before the team needs it. And when an unplanned need arises, like it always does, the project manager begs, borrows, and steals to secure what the team needs. And when they can’t get what’s needed, they apologize to the team, re-plan the project, reset the completion date, and deliver the bad news to those that don’t want to hear it.

If the General Manager says the project will be done in three months and the Project Manager thinks otherwise, put your money on the Project Manager.

Project Managers aren’t at the top of the org chart, but we punch above our weight. We’ve earned the trust and respect of most everyone. We aren’t liked by everyone, but we’re trusted by all. And we’re not always understood, but everyone knows our intentions are good. And when we ask for help, people drop what they’re doing and pitch in. In fact, they line up to help. They line up because we’ve gone out of our way to help them over the last decade. And they line up to help because we’ve put it on the table.

Whether it’s IoT, Digital Strategy, Industry 4.0, top-line growth, recurring revenue, new business models, or happier customers, it’s all about the projects. None of this is possible without projects. And the keystone of successful projects? You guessed it. Project Managers.

Image credit – Bernard Spragg .NZ

Stop, Start, Continue the Hard Way

The stop, start, continue method (SSC) is a simple, yet powerful, way to plan your day, week and year. And though it’s simple, it’s not simplistic. And though it looks straightforward, it’s onion-like in its layers.

The stop, start, continue method (SSC) is a simple, yet powerful, way to plan your day, week and year. And though it’s simple, it’s not simplistic. And though it looks straightforward, it’s onion-like in its layers.

Stop, start, continue (SSC) is interesting in that it’s forward-looking, present-looking, and rearward-looking at the same time. And its power comes from the requirement that the three time perspectives must be reconciled with each other. Stopping is easy, but what will start? Starting is easy, unless nothing is stopped. Continuing is easy, but it’s not the right thing if the rules have changed. And starting can’t start if everything continues.

Stop. With SSC, stopping is the most important part. That’s why it’s first in the sequence. When everyone’s plates are full and every meeting is an all-you-can-eat buffet, without stopping, all the new action items slathered on top simply slip off the plate and fall to the floor. And this is double trouble because while it’s clear new action items are assigned, there’s no admission that the carpet is soiled with all those recently added action items.

Here’s a rule: If you don’t stop, you can’t start.

And here’s another: Pros stop, and rookies start.

With continuous improvement, you should stop what didn’t work. But with innovation, you should stop what was successful. Let others fan the flames of success while you invent the new thing that will start a bigger blaze.

Start. With SSC, starting is the easy part, but it shouldn’t be. Resources are finite, but we conveniently ignore this reality so we can start starting. The trouble with starting is that no one wants to let go of continuing. Do everything you did last year and start three new initiatives. Continue with your current role, but start doing the new job so you can get the promotion in three years.

Here’s a rule: Starting must come at the expense of continuing.

And here’s another: Pros do stop, start, continue, and rookies do start, start, start.

Continue. With SSC, continue is underrated. If you’re always starting, it’s because you have nothing good to continue. And if you’ve got a lot of continuing to do, it’s because you’ve got a lot of good things going on. And continuing is efficient because you’re not doing something for the first time. And everyone knows how to do the work and it goes smoothly.

But there’s a dark side to continue – it’s called the status quo. The status quo is a powerful, one-trick pony that only knows how to continue. It hates stopping and blocks all starting. Continuing is the mortal enemy of innovation.

Here’s a rule: Continuing must stop, or starting can’t start.

And here’s another: Pros continue and stop before they start, and rookies start.

SSC is like juggling three balls at once. Just as it’s not juggling unless it’s three balls at the same time, it’s not SSC unless it’s stop, start, continue all done at the same time. And just as juggling two balls at once isn’t juggling, it’s not SSC if it’s just two out of the three. And just as dropping two of the three balls on the floor isn’t juggling, it’s not SSC if it’s starting, starting, starting.

Image credit – kosmolaut

A Recipe to Grow Talent

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it for them, then explain. When the work is new for them, they don’t know how to do it. You’ve got to show them how to do it and explain everything. Tell them about your top-level approach; tell them why you focus on the new elements; show them how to make the chart that demonstrates the new one is better than the old one. Let them ask questions at every step. And tell them their questions are good ones. Praise them for their curiosity. And tell them the answers to the questions they should have asked you. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do it with them, and let them hose it up. Let them do the work they know how to do, you do all the new work except for one new element, and let them do that one bit of new work. They won’t know how to do it, and they’ll get it wrong. And you’ve got to let them. Pretend you’re not paying attention so they think they’re doing it on their own, but pay deep attention. Know what they’re going to do before they do it, and protect them from catastrophic failure. Let them fail safely. And when then hose it up, explain how you’d do it differently and why you’d do it that way. Then, let them do it with your help. Praise them for taking on the new work. Praise them for trying. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help them when they need it. Let them lead the project, but stay close to the work. Pretend to be busy doing another project, but stay one step ahead of them. Know what they plan to do before they do it. If they’re on the right track, leave them alone. If they’re going to make a small mistake, let them. And be there to pick up the pieces. If they’re going to make a big mistake, casually check in with them and ask about the project. And, with a light touch, explain why this situation is different than it seems. Help them take a different approach and avoid the big mistake. Praise them for their good work. Praise them for their professionalism. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Let them do it, and help only when they ask. Take off the training wheels and let them run the project on their own. Work on something else, and don’t keep track of their work. And when they ask for help, drop what you are doing and run to help them. Don’t walk. Run. Help them like they’re your family. Praise them for doing the work on their own. Praise them for asking for help. And tell them they’re ready for the next level.

Do the new work for them, then repeat. Repeat the whole recipe for the next level of new work you’ll help them master.

Image credit — John Flannery

28 Things I Learned the Hard Way

- If you want to have an IoT (Internet of Things) program, you’ve got to connect your products.

- If you want to build trust, give without getting.

- If you need someone with experience in manufacturing automation, hire a pro.

- If the engineering team wants to spend a year playing with a new technology, before the bell rings for recess ask them what solution they’ll provide and then go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you don’t have the resources, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, let someone else do it.

- If you want to make a friend, help them.

- If your products are not connected, you may think you have an IoT program, but you have something else.

- If you don’t have trust, you have just what you earned.

- If you hire a pro in manufacturing automation, listen to them.

- If Marketing has an optimistic sales forecast for the yet-to-be-launched product, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you don’t have a project manager, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, teach someone else how to do it.

- If a friend needs help, help them.

- If you want to connect your products at a rate faster than you sell them, connect the products you’ve already sold.

- If you haven’t started building trust, you started too late.

- If you want to pull in the delivery date for your new manufacturing automation, instead, tell your customers you’ve pushed out the launch date.

- If the VP knows it’s a great idea, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you can’t commercialize, you don’t have a project.

- If you know how it will turn out, do something else.

- If a friend asks you twice for help, drop what you’re doing and help them immediately.

- If you can’t figure out how to make money with IoT, it’s because you’re focusing on how to make money at the expense of delivering value to customers.

- If you don’t have trust, you don’t have much

- If you don’t like extreme lead times and exorbitant capital costs, manufacturing automation is not for you.

- If the management team doesn’t like the idea, go ask customers how much they’ll pay and how many they’ll buy.

- If you’re not willing to finish a project, you shouldn’t be willing to start.

- If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

- If you see a friend that needs help, help them ask you for help.

Image credit — openDemocracy

When The Wheels Fall Off

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When the project’s unrealistic cost constraints wall of the design space where the solution resides, who would you call to open up the higher-cost design space?

When the project team has tried and failed to figure out the root cause of the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of it?

And when you bring in the regular experts and they, too, try and fail to fix the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of getting to the bottom of it?

When marketing won’t relax the specification and engineering doesn’t know how to meet it, who would you call to end the sword fight?

When engineering requires geometry that can only be made by a process that manufacturing doesn’t like and neither side will give ground, who would you call to converge on a solution?

When all your best practices haven’t worked, who would you call to invent a novel practice to right the ship?

When the wheels fall off, you need to know who to call.

If you have someone to call, don’t wait until the wheels fall off to call them. And if you have no one to call, call me.

Image credit — Jason Lawrence

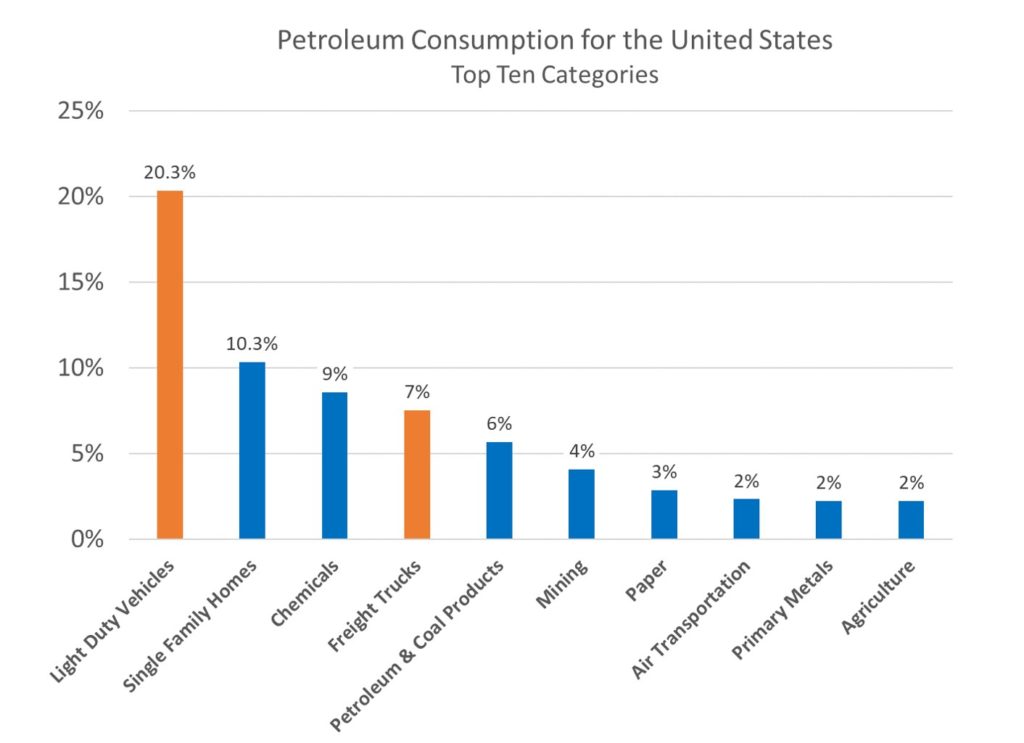

Where is petroleum consumed?

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

In last week’s post, I provided a chart that describes the sources of electricity for the United States. Coal is the largest source of electricity (38%) and natural gas is the next largest (25%). The largest non-carbon source is nuclear (22%) and the largest renewable sources are wind (6%) and solar (5%). The data from the chart came from Otherlab who was contracted by the Advanced Research Project Agency of the Department of Energy (ARPA-e) to review all available energy data sources and create an ultra-high resolution picture of the U.S. energy economy.

Using the same data set, I created a chart to break out the top ten categories for petroleum consumption for the United States.

The category Light-Duty Vehicles (cars, light trucks) is the largest consumer at 20% and is more than the sum of the next two categories – Single-Family Homes (10%) and Chemicals (9%).

When Light-Duty Vehicles at 20% are combined with Freight Trucks (think eighteen-wheelers) at 7%, they make up 27% of the country’s total consumption, making the Transportation sector the thirstiest. The most effective way to reduce petroleum consumption is to replace vehicles powered by internal combustion engines with electric vehicles (EVs). But there’s a catch.

As internal combustion engines diminish and EVs come online, petroleum consumption will drop and will help the planet. But, as EVs come online the demand for electricity will increase, making it even more important to replace coal and natural gas with zero-carbon sources of electricity: nuclear, hydro, wind and solar.

To save the planet, here’s what you can do. Vote for political candidates who will end federal subsidies for coal and natural gas. That single change will accelerate the adoption of wind and solar, as it will increase the existing cost advantage of wind and solar. And if that freed-up money can be reallocated to federally-funded R&D to improve the controllability of electrical grids, the change will come even sooner.

And at the state and local level, you can vote for candidates that want to make it easier for wind and solar projects to be funded.

And, lastly, you can buy an EV. You will see a much larger selection of new electric vehicles over the next year and the driving range continues to improve. Over the next year, most new EV models will be high performance and high cost, lower-cost EVs should follow soon after.

Image credit – NASA Goodard Flight Center

All-or-Nothing vs. One-in-a-Row

All-or-nothing thinking is exciting – we’ll launch a whole new product family all at once and take the market by storm! But it’s also dangerous – if we have one small hiccup, “all” turns into “nothing” in a heartbeat. When you take an all-or-nothing approach, it’s likely you’ll have far too little “all” and far too much “nothing”.

All-or-nothing thinking is exciting – we’ll launch a whole new product family all at once and take the market by storm! But it’s also dangerous – if we have one small hiccup, “all” turns into “nothing” in a heartbeat. When you take an all-or-nothing approach, it’s likely you’ll have far too little “all” and far too much “nothing”.

Instead of trying to realize the perfection of “all”, it’s far better to turn nothing into something. Here’s the math for an all-or-nothing launch of product family launch consisting of four products, where each product will create $1 million in revenue and the probability of launching each product is 0.5 (or 50%).

1 product x $1 million x 0.5 = $500K

2 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 = $500K

3 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = $375K

4 products x $1 million x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 x 0.5 = $250K

In the all-or-nothing scheme, the launch of each product is contingent on all the others. And if the probability of each launch is 0.5, the launch of the whole product family is like a chain of four links, where each link has a 50% chance of breaking. When a single link of a chain breaks, there’s no chain. And it’s the same with an all-or-nothing launch – if a single product isn’t ready for launch, there are no product launches.

But the math is worse than that. Assume there’s new technology in all the products and there are five new failure modes that must be overcome. With all-or-nothing, if a single failure mode of a single product is a problem, there are no launches.

But the math is even more deadly than that. If there are four use models (customer segments that use the product differently) and only one of those use models creates a problem with one of the twenty failure modes (five failure modes times four products) there can be no launches. In that way, if 25% of the customers have one problem with a single failure mode, there are can be no launches. Taken to an extreme, if one customer has one problem with one product, there can be no launches.

The problem with all-or-nothing is there’s no partial credit – you either launch four products or you launch none. Instead of all-or-nothing, think “secure the launch”. What must we do to secure the launch of a single product? And once that one’s launched, the money starts to flow. And once we launch the first one, what must we do to secure the launch the second? (More money flows.) And, once we launch the third one…. you get the picture. Don’t try to launch four at once, launch a single product four times in a row. Instead of all-or-nothing, think one-in-a-row, where revenue is achieved after each launch of a single launch.

And there’s another benefit to launching one at a time. The second launch is informed by learning from the first launch. And the third is informed by the first two. With one-in-a-row, the team gets smarter and each launch gets better.

Where all-or-nothing is glamorous, one-in-a-row is achievable. Where all-or-nothing is exciting, one-in-row is achievable. And where all-or-nothing is highly improbable, one-in-a-row is highly profitable.

Image credit – Mel

How To Know if You’re Moving in a New Direction

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

If you want to move in a new direction, you can call it disruption, innovation, or transformation. Or, if you need to rally around an initiative, call it Industrial Internet of Things or Digital Strategy. The naming can help the company rally around a new common goal, so take some time to argue about and get it right. But, settle on a name as quickly as you can so you can get down to business. Because the name isn’t the important part. What’s most important is that you have an objective measure that can help you see that you’ve stopped talking about changing course and started changing it.

When it’s time to change course, I have found that companies error on the side of arguing what to call it and how to go about it. Sure, this comes at the expense of doing it, but that’s the point. At the surface, it seems like there’s a need for the focus groups and investigatory dialog because no one knows what to do. But it’s not that the company doesn’t know what it must do. It’s that no one is willing to make the difficult decision and own the consequences of making it.

Once the decision is made to change course and the new direction is properly named, the talk may have stopped but the new work hasn’t started. And this is when it’s time to create an objective measure to help the company discern between talking about the course change and actively changing the course.

Here it is in a nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects change.

Here’s the failure mode to guard against. When the naming conventions in the operating plans reflect the new course heading but sitting under the flashy new moniker is the same set of tired, old projects. The job of the objective measure is to discern between the same old projects and new projects that are truly aligned with the new direction.

And here’s the other half of the nutshell. There can be no course change unless the projects solve different problems.

To discern if the company is working in a new direction, the objective measure is a one-page description of the new customer problem each project will solve. The one-page limit helps the team distill their work into a singular customer problem and brings clarity to all. And framing the problem in the customer’s context helps the team know the project will bring new value to the customer. Once the problem is distilled, everyone will know if the project will solve the same old problem or a new one that’s aligned with the company’s new course heading. This is especially helpful the company leaders who are on the hook to move the company in the new direction. And ask the team to name the customer. That way everyone will know if you are targeting the same old customer or new ones.

When you have a one-page description of the problem to be solved for each project in your portfolio, it will be clear if your company is working in a new direction. There’s simply no escape from this objective measure.

Of course, the next problem is to discern if the resources have actually moved off the old projects and are actively working on the new projects. Because if the resources don’t move to the new projects, you’re not solving new problems and you’re not moving in the new direction.

Image credit – Walt Stoneburner

People, Money and Time

If you want the next job, figure out why.

There’s nothing wrong with wanting the job you have.

When you don’t care about the next job it’s because you fit the one you have.

A larger salary is good, but time with family is better.

Less time with family is a downward spiral into sadness.

When you decide you have enough, you don’t need things to be different.

A sense of belonging lasts longer than a big bonus.

A cohesive team is an oasis.

Who you work with makes all the difference.

More stress leads to less sleep and that leads to more stress.

If you’re not sleeping well, something’s wrong.

How much sleep do you get? How do you feel about that?

Leaders lead people.

Helping others grow IS leadership.

Every business is in the people business.

To create trust, treat people like they matter. It’s that simple.

When you do something for someone even though it comes at your own expense, they remember.

You know you’ve earned trust when your authority trumps the org chart.

Image credit — Jimmy Baikovicius

Innovation Truths

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

If it’s not different, it can’t be innovation.

With innovation, ideas are the easy part. The hard part is creating the engine that delivers novel value to customers.

The first goal of an innovation project is to earn the right to do the second hardest thing. Do the hardest thing first.

Innovation is 50% customer, 50% technology and 75% business model.

If you know how it will turn out, it’s not innovation.

Don’t invest in a functional prototype until customers have placed orders for the sell-able product.

If you don’t know how the customer will benefit from your innovation, you don’t know anything.

If your innovation work doesn’t threaten the status quo, you’re doing it wrong.

Innovation moves at the speed of people.

If you know when you’ll be finished, you’re not doing innovation.

With innovation, the product isn’t your offering. Your offering is the business model.

If you’re focused on best practices, you’re not doing innovation. Innovation is about doing things for the first time.

If you think you know what the customer wants, you don’t.

Doing innovation within a successful company is seven times hard than doing it in a startup.

If you’re certain, it’s not innovation.

With innovation, ideas and prototypes are cheap, but building the commercialization engine is ultra-expensive.

If no one will buy it, do something else.

Technical roadblocks can be solved, but customer/market roadblocks can be insurmountable.

The first thing to do is learn if people will buy your innovation.

With innovation, customers know what they don’t want only after you show them your offering.

With innovation, if you’re not scared to death you’re not trying hard enough.

The biggest deterrent to innovation is success.

Image credit — Sherman Geronimo-Tan

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski