Archive for the ‘Fear’ Category

On Independence

Independence for a country is about choice. A country wants to be able to make choices to better itself, to control its own destiny. A country wants to feel like it has freedom to do what it thinks is right. Hopefully, a country thinks it’s a good to provide for its citizens in a long term sense. We can disagree what is best, but a good country makes an explicit choice about what it think is right and takes responsibility for its choices. For a country, the choices should be grounded in the long term.

Independence for a country is about choice. A country wants to be able to make choices to better itself, to control its own destiny. A country wants to feel like it has freedom to do what it thinks is right. Hopefully, a country thinks it’s a good to provide for its citizens in a long term sense. We can disagree what is best, but a good country makes an explicit choice about what it think is right and takes responsibility for its choices. For a country, the choices should be grounded in the long term.

Independence for a company is about choice. Like a country, a company wants control over its own destiny. A company wants to feel like it has freedom to do what’s right. A company wants to decide what’s right and wants the ability to act accordingly. There are lots of management theories on what’s right, but the company wants to be able to choose. Like it or not, the company will be accountable for its choices, as measured by stock price or profit.

And with children, independence is about choice. Children, too, want control over their own destiny, but they score low on the responsibility scale. And that’s why children earn responsibility over time – get a little, don’t get hurt, and get a little more. They don’t know what’s good for them, but don’t let that get in the way of wanting control over their own destiny. That’s why parents exist.

Independence is about the ability to choose. But there’s a catch. With independence comes responsibility – responsibility for the choice. With children, there’s insufficient responsibility because they just don’t care. And with employees in a company, there’s insufficient responsibility for another reason – fear of failure. I’m not sure about countries.

Independence is a two way street – choice and responsibility. And independence is bound by constraints. (There are unalienable rights, but unconstrained independence isn’t one of them.) For more independence, push hard on constraints; for more independence, take responsibility; for more independence, make more choices (and own the consequences).

Happy Independence Day.

Just Start

Starting is scary – we’re afraid to get it wrong. And we let our fear block us from starting. And that’s strange, because there’s never certainty on the right way because every situation is different. Fact is, you will be wrong, it’s just a matter of how wrong. But even the level of wrongness is not important. What’s important is starting because starting gives us the opportunity to respond to our wrongness. And that’s the trick – our response to being wrong is progress. Start, be wrong, refocus, and go. Progress.

Starting is scary – we’re afraid to get it wrong. And we let our fear block us from starting. And that’s strange, because there’s never certainty on the right way because every situation is different. Fact is, you will be wrong, it’s just a matter of how wrong. But even the level of wrongness is not important. What’s important is starting because starting gives us the opportunity to respond to our wrongness. And that’s the trick – our response to being wrong is progress. Start, be wrong, refocus, and go. Progress.

The biggest impediment to finishing is starting. Don’t let perfection get in the way of progress. Just start.

Impossible

Things aren’t impossible on their own, our thinking makes them so.

Things aren’t impossible on their own, our thinking makes them so.

Impossible is not about the thing itself, it’s a statement about our state of mind.

When we say impossible, we really say we lack confidence to try.

When we say impossible, we really say we are too afraid to try.

The mission of impossible is to shut down all possibility of possibility.

To soften it, we say almost impossible, but it’s the same thing.

When we say impossible, we make a big judgment – but not about the thing – about ourselves.

Untapped Power of Self

As a subject matter expert (SME), you have more power than you think, and certainly more than you demonstrate.

As a subject matter expert (SME), you have more power than you think, and certainly more than you demonstrate.

As an SME, you have special knowledge. Looking back, you know what worked, what didn’t, and why; looking forward, you know what should work, what shouldn’t, and why. There’s power in your special knowledge, but you underestimate it and don’t use it to move the needle.

As an SME, without your special knowledge there are no new products, no new technologies, and no new markets. Without it, it’s same-old, same-old until the competition outguns you. It’s time you realize your importance and behave that way.

As an SME, when you and your SME friends gang together, your company must listen. Your gang knows it all. From the system-level stuff to the most detailed detail, you know it. Remember, you invented the technology that powers your products. It’s time you behave that way.

As an SME, with your power comes responsibility – you have an obligation to use your power for good. Figure out what the technology wants, and do that; do the sustainable thing; do the thing that creates jobs; do what’s good for the economy; sit yourself in the future, look back, and do what you think is right.

As an SME, I’m calling you out. I trust you, now it’s time to trust yourself. And it’s time for you to behave that way.

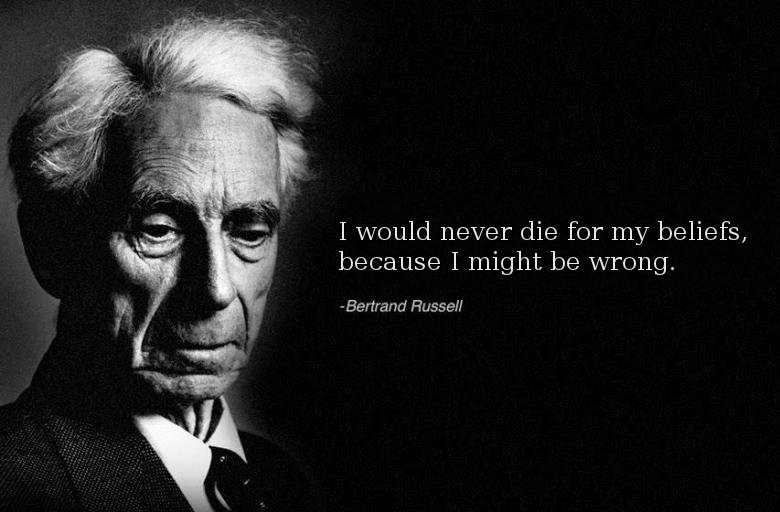

Beliefs Govern Ideas

Some ideas are so powerful they change you. More precisely, some ideas are so powerful you change your beliefs to fit them.

Some ideas are so powerful they change you. More precisely, some ideas are so powerful you change your beliefs to fit them.

These powerful ideas come in two strains: those that already align with your beliefs and those that contradict.

The first strain works subtly. While you think on the idea, your beliefs test it for safety. (They work in the background without your knowledge.) And if the idea passes the sniff test, and your beliefs feel safe, they let the subconscious sniffing morph into conscious realization – the idea fits your beliefs. The result: You now better understand your beliefs and you blossom, grow, and amplify yourself.

The second strain is subtle as a train wreck – a full frontal assault on your beliefs. This strain contradicts our beliefs and creates an emotional response – fear, anger, stress. And because these ideas threaten our beliefs, our beliefs reject them for safety’s sake. It’s like an autoimmune system for ideas.

But this autoimmune system has a back door. While it rejects most of the idea, for unknown reasons it passes a wisp to our belief system for sniffing. Like a vaccine, it wants to strengthen our beliefs against the strain. And in most cases, it works. But in rare cases, through deep introspection, our beliefs self-mutate and align with the previously contradicting idea. The result: You change yourself fundamentally.

Truth is, ideas are not about ideas; ideas are about beliefs. Our beliefs give life to ideas, or kill them. But we give ideas too much responsibility, and take too little. Truth is, we can change what we think and feel about ideas.

More powerfully, we can change what we think and feel about our beliefs, but only if we believe we can.

Work The Rule

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the rule makes things take too long, do you follow it or shortcut it?

If the reason for the rule is no longer, do you follow it or declare it unreasonable?

If you don’t understand the rule do you work to understand it, or conveniently trespass?

If you don’t follow the rule, does that say something about the rule, or you?

When is a rule a rule and when is it shackles?

When it comes to law, physics, and safety, a rule is a rule.

If you’re limited by the rule, is it bad? (Isn’t far worse if you don’t realize it?)

What if the solution demands unruliness?

If you don’t follow rules, is it okay to make them?

What if a culture is so strong it rules out most everything, except following the rules?

What if a culture is so strong it demands you make the rules?

When it comes to rules, there’s only one rule – You decide.

I will hold a Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

The Forbidden Fruit of Failure

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

We’ve mapped failure to the wrong words. And this mis-mapping is so strong and deep that un-mapping seems unlikely. I propose failure, as a word, be scratched from the dictionary.

Failure is learning in the form of experiments (including the thought kind) with outcomes different than theorized, where the outcomes create a more complete understanding of theory, or learning.

Wrong is mapped to failure, but failure should be mapped with – different than our best understanding.

Newness is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more newness, more learning. This is why tolerance of failure (and newness) is a must – no newness, no failure, no learning.

Risk is mapped to failure. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – more risk, more learning. Risk cannot be forbidden, if we’re to learn.

Risk and newness are mapped to late, and, guilt by association, failure is mapped to late. Replace failure with learning and the mapping is right – learn fast to avoid being late. And now, after several paragraphs of un-mapping, hopefully the re-substitution makes sense – fail fast to avoid being late.

Failure isn’t failure, failure is learning.

Creativity’s Mission Impossible

Whether it’s a top-down initiative or a bottom-up revolution, your choice will make or break it.

Whether it’s a top-down initiative or a bottom-up revolution, your choice will make or break it.

When you have the inspiration for a bottom-up revolution, you must be brave enough to engage your curiosity without self-dismissing. You’ll feel the automatic urge to self-reject – that will never work, too crazy, too silly, too loony – but you must resist. (Automatic self-rejection is the embodiment of your fear of failure.) At all costs you must preserve the possibility you’ll try the loony idea; you must preserve the opportunity to learn from failure; you must suspend judgment.

Now it’s time to tell someone your new thinking. Summon the next level of courage, and choose wisely. Choose someone knowledgeable and who will be comfortable when you slather them with the ambiguity. (No ambiguity, no new thinking.) But most importantly, choose someone who will suspend judgment.

You now have critical mass – you, your partner in crime, and your bias for action. Together you must prevent the new thinking from dying on the vine. Tell no one else, and try it. Try it at a small scale, try it in your garage. Fail-learn-fail until you have something with legs. Don’t ask. Suspend judgment, and do.

And what of top down initiatives? They start with bottom-up new thinking, so the message is the same: suspend judgment, engage your bias for action, and try it. This is the precursor to the thousand independent choices that self-coordinate into a top-down initiative.

New thinking is a choice, and turning it into action is another. But this is your mission, if you choose to accept it.

I will be holding a half-day Workshop on Systematic DFMA Deployment on June 13 in RI. (See bottom of linked page.) I look forward to meeting you in person.

Choose Your Path

There are only three things you can do:

There are only three things you can do:

1. Do what you’re told. This is fine once in a while, but not fine if you’re also told how.

2. Do what you’re not told. This is the normal state of things – good leaders let good people choose.

3. Do what you’re told not to. This is rarified air, but don’t rule it out.

Run From Your Success

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Don’t worry about your biggest competitor – they’re not your biggest competitor. You’ve not met your biggest competitor. Your biggest competitor is either from another industry or it’s three guys and a dog toiling away in their basement.

Certainly it’s impossible to worry about a competitor we’ve not met, but that’s just what we’ve got to do. We’ve got to use thought-shifting mechanisms to help us see ourselves from the framework of our unknown competitor.

Our unknown competitor doesn’t have much – no fully functional products, no fully built-out product lines, and no market share. And that’s where we must shift our thinking – to a place of scarcity – so we can see ourselves from their framework. We’ve got to look down (in the S-curve sense), sit ourselves at the bottom, and look up at our successful selves. It’s the best way to move from self-cherishing to self-dismantling.

To start, we must create our logical trajectory. First, define where we are and where we came from. Then, with a ruler aligned to the points, extend a line into the future. That’s our logical trajectory – an extrapolation in the direction of our success. Along this line we will do more of what got us here, more of what we’ve done. Without giving ground on any front, we will protect market share and build more. We’ve now defined how we see ourselves. We’ve now defined the thinking that could be our undoing.

Now we must force enlightenment on ourselves. We create an illogical trajectory where we see ourselves from a success-less framework. In this framework less is more; more-of-the-same is displaced with more-of-something-else; and success is a weakness. We know we’re sitting in the rights space when the smallest slice of incremental market share looks like a big, juicy bite – like it looks to our unknown competitor.

The disruptive technology created by our unknown competitor will start innocently. Immature at first, the disruptive technology will do most things poorly but do one thing better. Viewed from our success framework we will see only limitations and dismiss it, while our unknown competitors will see opportunity. We will see the does-most-things-poorly part and they’ll see the one-thing-better part. They will sell to a small segment that values the one-thing-better part.

In another variant, an immature disruptive technology will do less with far less. From our success framework we will see “less” while from their scarcity framework they will see “more”. They will sell a simpler product that does less for a price that’s far less. (And make money.)

Here’s the one that’s most frightening: an immature technology that does all things poorly but does them without a fundamental limitation of our technology. From our framework the limitation is so fundamental we won’t let ourselves see it. This limitation is un-seeable because we’ve built our business around it. (Think Kodak film.) This flavor of disruptive technology can put our business model out of business, yet we’ll dismiss it.

We’ll know we’ve shifted our thinking to the right place when we see our unknown competitors not as bottom-feeders but as hungry competitors who see our scraps as a smorgasbord.

We’ll know our thinking’s right when see not self-destruction, but self-disruption.

We’ll know all is right with the world we’re working on disruptive technologies to disrupt ourselves, disruptive technologies with the potential to create business models so compelling that we’ll gladly run from our success.

Can’t Say NO

- Yes is easy, no is hard.

- Sometimes slower is faster.

- Yes, and here’s what it will take:

- The best choose what they’ll not do.

- Judge people on what they say no to.

- Work and resources are a matched pair.

- Define the work you’ll do and do just that.

- Adding scope is easy, but taking it out is hard.

- Map yes to a project plan based on work content.

- Challenge yourself to challenge your thinking on no.

- Saying yes to something means saying no to something else.

- The best have chosen wrong before, that’s why they’re the best.

- It’s better to take one bite and swallow than take three and choke.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski