Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

Did you make a difference today?

Did you engage today with someone that needed your time and attention, though they didn’t ask? You had a choice to float above it all or recognize that your time and attention were needed. And then you had a follow-on choice: to keep on truckin’ or engage. If you recognized they needed your help, what caused you to spend the energy needed to do that? And if you took the further step to engage, why did you do that? For both questions, I bet the answer is the same – because you care about them and you care about the work. And I bet they know that and I bet you made a difference.

Did you alter your schedule today because something important came up? What caused you to do that? Was it about the thing that came up or the person(s) impacted by the thing that came up? I bet it was the latter. And I bet you made a difference.

Did you spend a lot of energy at work today? If so, why did you do that? Was it because you care about the people you work with? Was it because you care about your customers? Was it because you care enough about yourself to live up to your best expectations? I bet it was all those reasons. And I bet you made a difference.

Image credit — Dr. Matthias Ripp

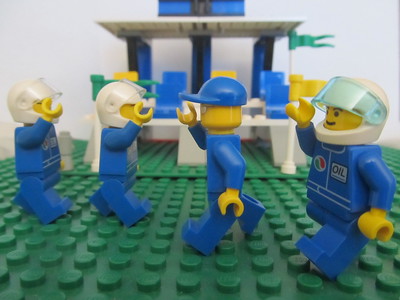

Small Teams are Mighty

When you want new thinking or rapid progress, create a small team.

When you want new thinking or rapid progress, create a small team.

When you have a small team, they manage the handoffs on their own and help each other.

Small teams hold themselves accountable.

With small teams, one member’s problem becomes everyone’s problem in record time.

Small teams can’t work on more than one project at a time because it’s a small team.

And when a small team works on a single project, progress is rapid.

Small teams use their judgment because they have to.

The judgment of small teams is good because they use it often.

On small teams, team members are loyal to each other and set clear expectations.

Small teams coordinate and phase the work as needed.

With small teams, waiting is reduced because the team members see it immediately.

When something breaks, small teams fix it quickly because the breakage is apparent to all.

The tight connections of a small team are magic.

Small teams are fun.

Small teams are effective.

And small teams are powered by trust.

“LEGO Octan pit crew celebrating High Five Day (held every third Thursday of April)” by Pest15 is marked with CC BY-SA 2.0.

When You Have No Slack Time…

When you have no slack time, you can’t start new projects.

When you have no slack time, you can’t start new projects.

When you have no slack time, you can’t run toward the projects that need your help.

When you have no slack time, you have no time to think.

When you have no slack time, you have no time to learn.

When you have no slack time, there’s no time for concern for others.

When you have no slack time, there’s no time for your best judgment.

When there is no slack time, what used to be personal becomes transactional.

When there is no slack time, any hiccup creates project slip.

When you have no slack time, the critical path will find you.

When no one has slack time, one project’s slip ripples delay into all the others.

When you have no slack time, excitement withers.

When you have no slack time, imagination dies.

When you have no slack time, engagement suffers.

When you have no slack time, burnout will find you.

When you have no slack time, work sucks.

When you have no slack time, people leave.

I have one question for you. How much slack time do you have?

“Hurry up Leonie, we are late…” by The Preiser Project is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Why are people leaving your company?

People don’t leave a company because they feel appreciated.

People don’t leave a company because they feel appreciated.

People don’t leave a company because they feel part of something bigger than themselves.

People don’t leave a company because they see a huge financial upside if they stay.

People don’t leave a company because they are treated with kindness and respect.

People don’t leave a company because they can make less money elsewhere.

People don’t leave a company because they see good career growth in their future.

People don’t leave a company because they know all the key players and know how to get things done.

People don’t leave the company so they can abandon their primary care physician.

People don’t leave a company because their career path is paved with gold.

People don’t leave a company because they are highly engaged in their work.

People don’t leave a company because they want to uproot their kids and start them in a new school.

People don’t leave a company because their boss treats them too well.

People don’t leave a company because their work is meaningful.

People don’t leave a company because their coworkers treat them with respect.

People don’t leave a company because they want to pay the commission on a real estate transaction.

People don’t leave a company because they’ve spent a decade building a Trust Network.

People don’t leave a company because they want their kids to learn to trust a new dentist.

People don’t leave a company because they have a flexible work arrangement.

People don’t leave a company because they feel safe on the job.

People don’t leave a company because they are trusted to use their judgment.

People don’t leave the company because they want the joy that comes from rolling over their 401k.

People don’t leave a company when they have the tools and resources to get the work done.

People don’t leave a company when their workload is in line with their capacity to get it done.

People don’t leave a company when they feel valued.

People don’t leave a company so they can learn a whole new medical benefits plan.

People don’t leave a job because they get to do the work the way they think it should be done.

So, I ask you, why are people leaving your company?

“Penguins on Parade” by D-Stanley is licensed under

Making Time To Give Thanks

The pandemic has taken much from us, but we’re still here. We have each other, and that’s something we can be thankful for.

The pandemic has taken much from us, but we’re still here. We have each other, and that’s something we can be thankful for.

But going forward, what will you do? Will you worry about making the right choice, or will you be thankful you have a choice? Or maybe both?

When things don’t go according to your arbitrarily set expectations, will you judge yourself negatively? Or will you give yourself some self-love and be okay with things as they are? Will you be angry that the universe didn’t bend to your will or will thankful that you have an opportunity to give it another try tomorrow? Or maybe a little of both?

When you see someone struggling, what will you do? Will you play the zero-sum game and save all your resources for yourself? Or will you be thankful for what you have and give some of your emotional energy to someone who is having a hard day? I don’t think Thanksgiving is a zero-sum game, but no need to take my word for it. What’s wrong with running your own experiment? You may find that by spending a little you’ll get a lot more in return.

Everything is a little harder these days. This is real and natural. We’ve been through a lot together. Last year we did everything we could just to keep our heads above water. We worked harder than ever just to break even. We’re worn down and yet there seems to be no relief in sight. And now, the not-so-subtle economic forces will push us to dismiss our tiredness and try to convince us to strive for improvements and productivity on all fronts. Where are the thanks in all that?

As people that care, we can give thanks. We can thank the people who gave us everything they had. Of course, their work wasn’t perfect (it never is), but they held it together and they made it happen. They deserve our thanks. A short phone call will do, and so will a short text. And for the people that gave everything they had and couldn’t hold it together, they deserve our thanks more than anyone. They gave so much to others that they had nothing in reserve for themselves. They deserve our thanks, and we are just the people to give it to them.

What we were able to pull off last year is amazing. And that’s something we can be thankful for. So, give yourself thanks and feel good about it. And, if you have anything left in your tank, think about those special people that gave too much and paid the price. They need your thanks, too. And, remember, a short phone call or text is all it takes to give thanks.

Next year will be difficult. The world will ask us to step it up, even though we’re not ready. We’ll be asked to do more, even though our emotional gas tanks are empty. Let’s help each other get ready for next year by giving thanks to each other. Why not reach out to three to five people who made a difference over the last year and thank them?

And, remember, all it takes to give thanks is a short phone call or text.

Happy Thanksgiving.

“Two Hands Making a Heart with Sunset in Background” by Image Catalog is marked with CC0 1.0

If you want to understand innovation, understand novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

If you want to get innovation right, focus on novelty.

Novelty is the difference between how things are today and how they might be tomorrow. And that comparison calibrates tomorrow’s idea within the context of how things are today. And that makes all the difference. When you can define how something is novel, you have an objective measure of things.

How is it different than what you did last time? If you don’t know, either you don’t know what you did last time or you don’t know the grounding principle of your new idea. Usually, it’s a little of the former and a whole lot of the latter. And if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t learn how potential customers will react to the novelty. In fact, if you don’t know how it’s different, you can’t even decide who are the right potential customers.

A new idea can be novel in unique ways to different customer segments and it can be novel in opposite ways to intermediaries or other partners in the business model. A customer can see the novelty as something that will make them more profitable and an intermediary can see that same novelty as something that will reduce their influence with the customer and lead to their irrelevance. And, they’ll both be right.

Novelty is in the eye of the beholder, so you better look at it from their perspective.

Like with hot sauce, novelty comes in a range of flavors and heat levels. Some novelty adds a gentle smokey flavor to your favorite meal and makes you smile while the ghost pepper variety singes your palate and causes you to lose interest in the very meal you grew up on. With novelty, there is no singular level of Scoville Heat Unit (SHU) that is best. You’ve got to match the heat with the situation. Is it time to improve things a bit with a smokey, yet subtle, chipotle? Or, is it time to submerge things in pure capsaicin and blow the roof off? The good news is the bad news – it’s your choice.

With novelty, you can choose subtle or spicy. Choose wisely.

And like with hot sauce, novelty doesn’t always mix well with everything else on the plate. At the picnic, when you load your plate with chicken wings, pork ribs, and apple pie, it’s best to keep the hot sauce away from the apple pie. Said more strongly, with novelty, it’s best to use separate plates. Separate the teams – one team to do heavy novelty work, the disruptive work, to obsolete the status quo, and a separate team to the lighter novelty work, the continuous improvement work, to enhance the existing offering.

Like with hot sauce, different people have different tolerance levels for novelty. For a given novelty level, one person can be excited while another can be scared. And both are right. There’s no sense in trying to change a person’s tolerance for novelty, they either like it or they don’t. Instead of trying to teach them to how to enjoy the hottest hot sauce, it’s far more effective to choose people for the project whose tolerance for novelty is in line with the level of novelty required by the project.

Some people like habanero hot sauce, and some don’t. And it’s the same with novelty.

Your core business is your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

Your core business, the long-standing business that has made you what you are, is both your greatest strength and your greatest weakness.

The Core generates the revenue, but it also starves fledgling businesses so they never make it off the ground.

There’s a certainty with the Core because it builds on success, but its success sets the certainty threshold too high for new businesses. And due to the relatively high level of uncertainty of the new business (as compared to the Core) the company can’t find the gumption to make the critical investments needed to reach orbit.

The Core has generated profits over the decades and those profits have been used to create the critical infrastructure that makes its success easier to achieve. The internal startup can’t use the Core’s infrastructure because the Core doesn’t share. And the Core has the power to block all others from taking advantage of the infrastructure it created.

The Core has grown revenue year-on-year and has used that revenue to build out specialized support teams that keep the flywheel moving. And because the Core paid for and shaped the teams, their support fits the Core like a glove. A new offering with a new value proposition and new business model cannot use the specialized support teams effectively because the new offering needs otherly-specialized support and because the Core doesn’t share.

The Core pays the bills, and new ventures create bills that the Core doesn’t like to pay.

If the internal startup has to compete with the Core for funding, the internal startup will fail.

If the new venture has to generate profits similar to the Core, the venture will be a misadventure.

If the new offering has to compete with the Core for sales and marketing support, don’t bother.

If the fledgling business’s metrics are assessed like the Core’s metrics, it won’t fly, it will flounder.

If you try to run a new business from within the Core, the Core will eat it.

To work effectively with the Core, borrow its resources, forget how it does the work, and run away.

To protect your new ventures from the Core, physically separate them from the Core.

To protect your new businesses from the Core, create a separate budget that the Core cannot reach.

To protect your internal startup from the Core, make sure it needs nothing from the Core.

To accelerate the growth of the fledgling business, make it safe to violate the Core’s first principles.

To bolster the capability of your new business, move resources from the Core to the new business.

To de-risk the internal startup, move functional support resources from the Core to the startup.

To fund your new ventures, tax the Core. It’s the only way.

“Core Memory” by JD Hancock is licensed under CC BY 2.0

If you “don’t know,” you’re doing it right.

If you know how to do it, it’s because you’ve done it before. You may feel comfortable with your knowledge, but you shouldn’t. You should feel deeply uncomfortable with your comfort. You’re not trying hard enough, and your learning rate is zero.

If you know how to do it, it’s because you’ve done it before. You may feel comfortable with your knowledge, but you shouldn’t. You should feel deeply uncomfortable with your comfort. You’re not trying hard enough, and your learning rate is zero.

Seek out “don’t know.”

If you don’t know how to do it, acknowledge you don’t know, and then go figure it out. Be afraid, but go figure it out. You’ll make mistakes, but without mistakes, there can be no learning.

No mistakes, no learning. That’s a rule.

If you’re getting pressure to do what you did last time because you’re good at it, well, you’re your own worst enemy. There may be good profits from a repeat performance, but there is no personal growth.

Why not find someone with “don’t know” mind and teach them?

Find someone worthy of your time and attention and teach them how. The company gets the profits, an important person gets a new skill, and you get the satisfaction of helping someone grow.

No learning, no growth. That’s a rule.

No teaching, no learning. That’s a rule, too.

If you know what to do, it’s because you have a static mindset. The world has changed, but you haven’t. You’re walking an old cowpath. It’s time to try something new.

Seek out “don’t know” mind.

If you don’t know what to do, it’s because you recognize that the old way won’t cut it. You know have a forcing function to follow. Follow your fear.

No fear, no growth. That’s a rule.

Embrace the “don’t know” mind. It will help you find and follow your fear. And don’t shun your fear because it’s a leading indicator of novelty, learning, and growth.

“O OUTRO LADO DO MEDO É A LIBERDADE (The Other Side of the Fear is the Freedom)” by jonycunha is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Success Strangles

Success demands people do what they did last time.

Success demands people do what they did last time.

Success blocks fun.

Success walls off all things new.

Success has a half-life that is shortened by doubling down.

Success eats novelty for breakfast.

Success wants to scale, even when it’s time to obsolete itself.

Success doesn’t get caught from behind, it gets disrupted from the bottom.

Success fuels the Innovator’s Dilemma.

Success has a short attention span.

Success scuttles things that could reinvent the industry.

Success frustrates those who know it’s impermanent.

Success breeds standard work.

Success creates fear around making mistakes.

Success loves a best practice, even after it has matured into bad practice.

Success doesn’t like people with new ideas.

Success strangles.

Success breeds success, right up until the wheels fall off.

Success is the antidote to success.

“20204-roots strangle bricks” by oliver.dodd is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Taking vacations and holidays are the most productive things you can do.

It’s not a vacation unless you forget about work.

It’s not a vacation unless you forget about work.

It’s not a holiday unless you leave your phone at home.

If you must check-in at work, you’re not on vacation.

If you feel guilty that you did not check-in at work, you’re not on holiday.

If you long for work while you’re on vacation, do something more interesting on vacation.

If you wish you were at work, you get no credit for taking a holiday.

If people know you won’t return their calls, they know you are on vacation.

If people would rather make a decision than call you, they know you’re on holiday.

If you check your voicemail, you’re not on vacation.

If you check your email, you’re not on holiday.

If your company asks you to check-in, they don’t understand vacation.

If people at your company invite you to a meeting, they don’t understand holiday.

Vacation is productive in that you return to work and you are more productive.

Holiday is not wasteful because when you return to work you don’t waste time.

Vacation is profitable because when you return you make fewer mistakes.

Holiday is skillful because when you return your skills are dialed in.

Vacation is useful because when you return you are useful.

Holiday is fun because when you return you bring fun to your work.

If you skip your vacation, you cannot give your best to your company and to yourself.

If neglect your holiday, you neglect your responsibility to do your best work.

Don’t skip your vacation and don’t neglect your holiday. Both are bad for business and for you.

“CatchingButterflies on Vacation” by OakleyOriginals is licensed under CC BY 2.0

When you don’t know the answer, what do you say?

When you are asked a question and you don’t know the answer, what do you say? What does that say about you?

When you are asked a question and you don’t know the answer, what do you say? What does that say about you?

What happens to people in your organization who say “I don’t know.”? Are they lauded or laughed at? Are they promoted, overlooked, or demoted? How many people do you know that have said: “I don’t know.”? And what does that say about your company?

When you know someone doesn’t know, what do you do? Do you ask them a pointed question in public to make everyone aware that the person doesn’t know? Do you ask oblique questions to raise doubt about the person’s knowing? Do you ask them a question in private to help them know they don’t know? Do you engage in an informal discussion where you plant the seeds of knowing? And how do you feel about your actions?

When you say “I don’t know.” you make it safe for others to say it. So, do you say it? And how do you feel about that?

When you don’t know and you say otherwise, decision quality suffers and so does the company. Yet, some companies make it difficult for people to say “I don’t know.” Why is that? Do you know?

I think it’s unreasonable to expect people to know the answer to know the answers to all questions at all times. And when you say “I don’t know.” it doesn’t mean you’ll never know; it means you don’t know at this moment. And, yet, it’s difficult to say it. Why is that? Do you know?

Just because someone asks a question doesn’t mean the answer must be known right now. It’s often premature to know the answer, and progress is not hindered by the not knowing. Why not make progress and figure out the answer when it’s time for the answer to be known? And sometimes the answer is unknowable at the moment. And that says nothing about the person that doesn’t know the answer and everything about the moment.

It’s okay if you don’t know the answer. What’s not okay is saying you know when you don’t. And it’s not okay if your company makes it difficult for you to say you don’t know. Not only does that create a demoralized workforce, but it’s also bad for business.

Why do companies make it so difficult to say “I don’t know.”? You guessed it – I don’t know.

“Question Mark Cookies 1” by Scott McLeod is licensed under CC BY 2.0

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski