Archive for the ‘Culture’ Category

Why We Wait

We wait because we don’t have enough information to make a decision.

We wait because we don’t have enough information to make a decision.

We wait until the decision makes itself because no one wants to be wrong.

We wait for permission because of the negative consequences of being wrong.

We wait to use our judgment until we have evidence our judgment is right.

We wait for support resources because they are spread over too many projects.

We wait for a decision to be made because no one is sure who makes it.

We wait to reduce risk.

We wait to reduce costs.

We wait to move at the speed of trust.

We wait because too many people must agree.

We wait because disagreement comes too slowly.

We wait for disagreement because we don’t subscribe to “clear is kind.”

We wait when decisions are unmade.

We wait because there is insufficient courage to stop the bad projects.

We wait to stop things slowly.

We use waiting as a slow no.

We wait to reallocate resources because even bad projects have momentum.

We wait when we dislike the impending outcome.

We wait for the critical path.

We wait out of fear.

Image credit — Sylvia Sassen

The Power of Praise

When you catch someone doing good work, do you praise them? If not, why not?

When you catch someone doing good work, do you praise them? If not, why not?

Praise is best when it’s specific – “I think it was great when you [insert specific action here].”

If praise isn’t authentic, it’s not praise.

When you praise specific behavior, you get more of that great behavior. Is there a downside here?

As soon as you see praise-worthy behavior, call it by name. Praise best served warm.

Praise the big stuff in a big way.

Praise is especially powerful when delivered in public.

If praise feels good when you get it, why not help someone else feel good and give it?

If you make a special phone call to deliver praise, that’s a big deal.

If you deliver praise that’s inauthentic, don’t.

Praise the small stuff in a small way.

Outsized praise doesn’t hit the mark like the real deal.

There can be too much praise, but why not take that risk?

If praise was free to give, would you give it? Oh, wait. Praise is free to give. So why don’t you give it?

Praise is powerful, but only if you give it.

Image credit — Llima Orosa

Going Against The Grain

If you have nothing to say, be the person that doesn’t say it.

If you have nothing to say, be the person that doesn’t say it.

If you’re not the right person to do it, you’re also the right person not to do it. Why is it so difficult for to stop doing what no longer makes sense?

If it made sense to do it last time, it’s not necessarily the right thing to do this time, even if it was successful last time. But if it was successful last time, it will be difficult to do something different this time.

If we always standardize on what we did last time, mustn’t this time always be the same as last time? And musn’t next time always be the same as this time?

If it’s new, it’s scary. And if it’s scary, it’s bad. And we don’t like to get in trouble for doing bad things. And that’s why it’s difficult to do new things.

Deming said to “Drive out fear.” But that’s scary. What are the attributes of the people willing to face the fear and demonstrate that fear can be overcome? At your company are they promoted? Do they stay? Do they leave?

Without someone overcoming their internal fear, there can be no change.

If a new thing is blocked from commercialization because it wasn’t invented here, why not reinvent it just as it is, declare ownership, and commercialize it?

If prevention is worth a pound of cure, why do people that put out forest fires get the credit while those that prevent them go unnoticed? Does that mean your career will benefit it you start small fires in private and put them out quickly for all to see?

If you always do what’s best for your career, that’s not good for your career.

When you do something that’s good for someone’s career but comes at the expense of yours, that’s good for your career.

Why not say nothing when nothing is the right thing to say?

Why not say no when no is the right thing to say?

Why not do something new even though it’s different than what was successful last time?

Why not demonstrate fearlessness and break the trail for others?

Why not be afraid and do it anyway?

Why not build on something developed by another team and give them credit?

Why not do what’s right instead of doing what’s right for your career?

Why not do something for others? As it turns out, that’s the best thing to do for yourself.

Image credit — Steve Hammond

Projects, Products, People, and Problems

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

With projects, there is no partial credit. They’re done or they’re not.

Solve the toughest problems first. When do you want to learn the problem is not solvable?

Sometimes slower is faster.

Problems aren’t problems until you realize you have them. Before that, they’re problematic.

If you can’t put it on one page, you don’t understand it. Or, it’s complex.

Take small bites. And if that doesn’t work, take smaller bites.

To get more projects done, do fewer of them.

Say no.

Stop starting and start finishing.

Effectiveness over efficiency. It’s no good to do the wrong thing efficiently.

Function first, no exceptions. It doesn’t matter if it’s cheaper to build if it doesn’t work.

No sizzle, no sale.

And customers are the ones who decide if the sizzle is sufficient.

Solve a customer’s problem before solving your own.

Design it, break it, and fix it until you run out of time. Then launch it.

Make the old one better than the new one.

Test the old one to set the goal. Test the new one the same way to make sure it’s better.

Obsolete your best work before someone else does.

People grow when you create the conditions for their growth.

If you tell people what to do and how to do it, you’ll get to eat your lunch by yourself every day.

Give people the tools, time, training, and a teacher. And get out of the way.

If you’ve done it before, teach someone else to do it.

Done right, mentoring is good for the mentor, the mentee, and the bottom line.

When in doubt, help people.

Trust is all-powerful.

Whatever business you’re in, you’re in the people business.

Image credit — Hartwig HKD

What does it mean to have enough?

What does it mean to have enough?

What does it mean to have enough?

If you don’t want more, doesn’t that mean you have enough?

And if you want what you have, doesn’t that mean you don’t want more?

If you had more, would that make things better?

If you had more, what would stop you from wanting more?

What would it take to be okay with what you have?

If you can’t see what you have and then someone helps you see it, isn’t that like having more?

What do you have that you don’t realize you have?

Do you have a pet?

Do you have the ability to walk?

Do you have friends and family?

Do you have people that rely on you?

Do you have a place where people know you?

Do you have people that care about you?

Do you have a warm jacket and hat?

When you have enough you have the freedom to be yourself.

And when you have enough it’s because you decided you have enough.

Image credit — Irudayam

The Three Ts of Empowerment

If you give a person the tools, time, and training, you’ve empowered them. They know what to do, they have supporting materials, and they have the permission to spend the time they need to get it done.

If you give a person the tools, time, and training, you’ve empowered them. They know what to do, they have supporting materials, and they have the permission to spend the time they need to get it done.

If you give a person the tools and the time but not the training, they will struggle to figure out the tools but they’ll likely get there in the end. It won’t be all that efficient, but because you’ve given them the time they’ll be able to figure out the tools and get it done.

If you give a person the time but not the tools or the training, they’ll go on a random walk and make no progress. Yes, you’ve given them the time, but you’ve given them no real support or guidance. They’ll likely become tired and frustrated and you’ll have allocated their time yet made no progress.

If you give a person the tools and training but not the time, you’ve demoralized them. They have new skills and new tools and want to use them, but they’re too busy doing their day job. This is the opposite of empowerment.

If you’re not willing to give people the time to do new work, don’t bother providing new tools, and don’t bother training them. Stay the course and accept things as they are. Otherwise, you’ll disempower your best people.

But if you want to empower people, give them all three – tools, time, and training.

Image credit — Paul Balfe

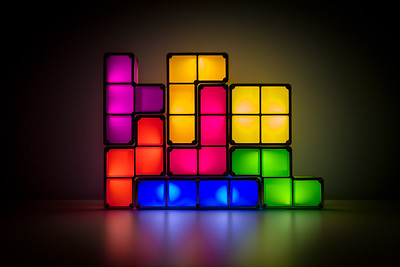

Playing Tetris With Your Project Portfolio

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

When planning the projects for next year, how do you decide which projects are a go and which are a no? One straightforward way is to say yes to projects when there are resources lined up to get them done and no to all others. Sure, the projects must have a good return on investment but we’re pretty good at that part. But we’re not good at saying no to projects based on real resource constraints – our people and our budgets.

It’s likely your big projects are well-defined and well-staffed. The problem with these projects is usually the project timeline is disrespectful of the work content and the timeline is overly optimistic. If the project timeline is shorter than that of a previously completed project of a similar flavor, with a similar level of novelty and similar resource loading, the timeline is overly optimistic and the project will be late.

Project delays in the big projects block shared resources from moving onto other projects within the appropriate time window which cascades delays into those other projects. And the project resources themselves must stay on the big projects longer than planned (we knew this would happen even before the project started) which blocks the next project from starting on time and generates a second set of delays that rumble through the project portfolio. But the big projects aren’t the worst delay-generating culprits.

The corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are usually well-staffed with centralized resources but these projects require significant work from the business units and is an incremental demand for them. And the only place the business units can get the resources is to pull them off the (too many) big projects they’ve already committed to. And remember, the timelines for those projects are overly optimistic. The big projects that were already late before the corporate initiatives and infrastructure projects are slathered on top of them are now later.

Then there are small projects that don’t look like they’ll take long to complete, but they do. And though the project plan does not call for support resources (hey, this is a small project you know), support resources are needed. These small projects drain resources from the big projects and the support resources they need. Delay on delay on delay.

Coming out of the planning process, all teams are over-booked with too many projects, too few resources, and timelines that are too short. And then the real fun begins.

Over the course of the year, new projects arise and are started even though there are already too few resources to deliver on the existing projects. Here’s a rule no one follows: If the teams are fully-loaded, new projects cannot start before old ones finish.

It makes less than no sense to start projects when resources are already triple-double booked on existing projects. This behavior has all the downside of starting a project (consumption of resources) with none of the upside (progress). And there’s another significant downside that most don’t see. The inappropriate “starting” of the new project allows the company to tell itself that progress is being made when it isn’t. All that happens is existing projects are further starved for resources and the slow pace of progress is slowed further.

It’s bad form to play Tetris with your project portfolio.

Running too many projects in parallel is not faster. In fact, it’s far slower than matching the projects to the resources on-hand to do them. It’s essential to keep in mind that there is no partial credit for starting a project. There is 100% credit for finishing a project and 0% credit for starting and running a project.

With projects, there are two simple rules. 1) Limit the number of projects by the available resources. 2) Finish a project before starting one.

Image credit – gerlos

When you say yes to one thing, you say no to another.

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

Life can get busy and complicated, with too many demands on our time and too little time to get everything done. But why do we accept all the “demands” and why do we think we have to get everything done? If it’s not the most important thing, isn’t a “demand for our time” something less than a demand? And if some things are not all that important, doesn’t it say we don’t have to do everything?

When life gets busy, it’s difficult to remember it’s our right to choose which things are important enough to take on and which are not. Yes, there are negative consequences of saying no to things, but there are also negative consequences of saying yes. How might we remember the negative consequences of yes?

When you say to yes to one thing, you say no to the opportunity to do something else. Though real, this opportunity cost is mostly invisible. And that’s the problem. If your day is 100% full of meetings, there is no opportunity for you to do something that’s not on your calendar. And in that moment, it’s easy to see the opportunity cost of your previous decisions, but that doesn’t do you any good because the time to see the opportunity cost was when you had the choice between yes and no.

If you say yes because you are worried about what people will think if you say no, doesn’t that say what people think about you is important to you? If you say yes because your physical health will improve (exercise), doesn’t that say your health is important to you? If you say yes to doing the work of two people, doesn’t it say spending time with your family is less important?

Here’s a proposed system to help you. Open your work calendar and move one month into the future. Create a one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. You just created a timeslot where you said no in the future to unimportant things and said yes in the future to important things. Now, make a list of three important things you want to do during those times. And after one month of this, create a second one-hour recurring meeting with yourself. Now you have two hours per week where you can prioritize things that are important to you. Repeat this process until you have allocated four hours per week to do the most important things. You and stop at four hours or keep going. You’ll know when you get the balance right.

And for Saturday and Sunday, book a meeting with yourself where you will do something enjoyable. You can certainly invite family and/or friends, but it the activity must be for pure enjoyment. You can start small with a one-hour event on Saturday and another on Sunday. And, over the weeks, you can increase the number and duration of the meetings.

Saying yes in the future to something important is a skillful way to say no in the future to something less important. And as you use the system, you will become more aware of the opportunity cost that comes from saying yes.

Image credit – Gilles Gonthier

Overcoming Not Invented Here (NIH), The Most Powerful Blocker of Innovation

When new ideas come from the outside, they are dismissed out of hand. The technical term for this behavior is Not Invented Here (NIH). Because it was not invented by the party with official responsibility, that party stomps it into dust. But NIH doesn’t stomp in public; it stomps in mysterious ways.

When new ideas come from the outside, they are dismissed out of hand. The technical term for this behavior is Not Invented Here (NIH). Because it was not invented by the party with official responsibility, that party stomps it into dust. But NIH doesn’t stomp in public; it stomps in mysterious ways.

Wow! That’s a great idea! Then, mysteriously, no progress is made and it dies a slow death.

That’s cool! Then there’s a really good reason why it can’t be worked.

That’s interesting! Then that morphs into the kiss of death.

We never thought of that. But it won’t scale.

That’s novel! But no one is asking for it.

That’s terribly exciting! We’ll study it into submission.

That’s incredibly different! And likely too different.

When the company’s novel ideas die on the vine, they likely die at the hands of NIH. If you can’t understand why a novel idea never made it out of the lab, investigate the crime scene and you may find NIH’s fingerprints. If customers liked the new idea yet it went nowhere, it could be NIH was behind the crime. If it makes sense, but it doesn’t make progress, NIH is the prime suspect.

If a team is not receptive to novel ideas from the outside, it’s because they consider their own ideas sufficiently good to meet their goals. Things are going well and there’s no reason to adopt new ideas from the outside. And buried in this description are the two ways to overcome NIH.

The fastest way to overcome NIH is to help a new idea transition from an idea conceived by someone outside the team to an idea created by someone inside the team. Here’s how that goes. The idea is first demonstrated by the external team in the form of a functional prototype. This first step aims to help the internal team understand the new idea. Then, the first waiting period is endured where nothing happens. After the waiting period, a somewhat different functional prototype is created by the external team and shown to the internal team. The objective is to help the internal team understand the new idea a little better. Then, the second waiting period is endured where nothing happens. Then, a third functional prototype is created and shown to the internal team. This time, shortcomings are called out by the external team that can only be addressed by the internal team. Then, the last waiting period is endured. Then, after the third waiting period, the internal team addresses the shortcomings and makes the idea their own. NIH is dead, and it’s off to the races.

The second fastest way to overcome NIH is to wait for the internal team to transition to a team that is receptive to new ideas initiated outside the team. The only way for a team to make the transition is for them to realize that their internal ideas are insufficient to meet their objectives. This can only come after their internal ideas are shown to be inadequate multiple times. Only after exhausting all other possibilities, will a team consider ideas generated from outside the team.

When the external team recognizes the internal team is out of ideas, they demonstrate a functional prototype to the internal team. And they do it in an “informational” way, meaning the prototype is investigatory in nature and not intended to become the seed of the internal team’s next generation platform. And as it turns out, it’s only a strange coincidence that the functional prototype is precisely what the internal team needs to fuel the next-generation platform. And the prototype is not fully wrung out. And as it turns out, the parts that need to be wrung out are exactly what the external team knows how to do. And when the internal team needs expertise from the external team to address the novel elements, as it turns out the external team conveniently has the time to help out.

Not Invented Here (NIH) is real. And it’s a powerful force. And it can be overcome. And when it is overcome, the results are spectacular.

Image credit — Becky Mastubara

Bucking The Best Practice

Doing what you did last works well, right up until it doesn’t.

Doing what you did last works well, right up until it doesn’t.

When you put 100% effort into doing what you did last time and get 80% of the output of last time, it’s time to do something different next time.

If it worked last time, but the environment or competition has changed, chances are it won’t work this time.

You can never step in the same river twice, and it’s the same with best practices.

Doing what you did last time is predictable until it isn’t.

The cost of trying the same thing too often is the opportunity cost of unlearned learning, which only comes from doing new things in new ways.

Our accounting systems don’t know how to capture the lost value due to unlearned learning, but your competition does.

Doing what you did last time may be efficient, but that doesn’t matter when it becomes ineffective.

Without new learning, you have a tired business model that will give you less year on year.

If you do what you did last time, you slowly learn what no longer works, but that’s all.

The best practice isn’t best when the context is different.

It’s not okay to do what you did last time all the time.

If you always do what you did last time, you don’t grow as a person.

If you do what you did last time, there are no upside surprises but there may be downside surprises.

Doing what you did last time is bad for your brain and your business.

How much of your work is repeating what you did last time? And how do you feel about that?

If you are tired of doing what you did last time, what are you going to do about it?

Might you sneak in some harmless novelty when no one is looking?

Might you conspire to try something new without raising the suspicion of the Standard Work Police?

Might you run a small experiment where the investment is small but the learning could be important?

Might you propose trying something new in a small way, highlighting the potential benefit and the safe-to-fail nature of the approach?

Might you propose small experiments run in parallel to increase the learning rate?

Might you identify an important problem that has never been solved and try to solve it?

Might you come up with a new solution that radically grows company profits?

Might you create a solution that obsoletes your company’s most profitable offering?

Might you bring your whole self to your work and see what happens?

Image credit – Marc Dalmulder

Start, Stop, Continue Gone Bad

Stop, Start, Continue is a powerful, straightforward way to manage things.

Stop, Start, Continue is a powerful, straightforward way to manage things.

If it’s not working, Stop.

If it’s working well, Continue.

If there’s a big opportunity to grow, Start.

Sounds pretty simple, but it’s often executed poorly.

The most dangerous variant of Stop, Start, Continue is Start, Start, Continue. Regardless of how well projects are doing, they Continue. The market has changed but the product hasn’t launched yet, Continue the project. Though the technical risk is increasing instead of decreasing, keep your mouth shut and Continue the project. Though resources have moved to different projects (that have recently started), Continue the project and pretend progress is being made. And though Continue is a big problem, Starting is a bigger one.

With Start, Start, Continue, the company’s eyes are too big for their stomach. Because there is no mechanism to limit the start of new projects based on the available resources (people, tools, infrastructure), projects start without the resources needed to get them done. In the short term, there’s a celebration because an important new project has started. But a month later, everyone on the project team knows the project is doomed because the project is largely unstaffed. And because of the tight lips, no one in company leadership knows there’s a problem. The telltale signs of Start, Start, Continue are long projects (insufficient resources) and a lack of Finishing (too many projects and too little focus).

There is a little-known process that can overpower Start, Start, Continue. It’s called Stop, Stop, Stop. It’s simple and powerful.

With Stop, Stop, Stop, stalled projects are stopped and resources are freed up to accelerate the best remaining projects. Think of it as moving from Continue existing projects to Accelerate the most important projects. And with Stop, Stop, Stop, there is no starting. None. There is only stopping, at least to start. Pet projects are stopped. Long-in-the-tooth projects are stopped. Irrelevant projects are stopped. And even good projects are stopped to allow great projects to Start.

With Stop, Stop, Stop, at least two projects must stop before a new project can start. And it’s better to stop three.

The result of Stop, Stop, Stop is a glut of freed-up resources that can be applied to amazing new projects. And because the resources are unallocated and ready to go, those new projects can be fully staffed and can make progress quickly. And because there are now fewer projects overall, the shared resources can respond more quickly for double acceleration. And with fewer projects, there are fewer resource collisions among projects and fewer slowdowns. Triple acceleration and a lighter project management burden.

If your projects are moving too slowly, use Stop, Stop, Stop to stop the worst projects. If you have too many projects and too few resources, Stop, Stop, Stop can set you free. If you want to Start an amazing new project, use Stop, Stop, Stop to free up the resources to make it happen.

Before you Start, Stop. And before you Continue, Stop. And instead of pretending to Stop or talking about Stopping, Stop.

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski