Archive for the ‘Clarity’ Category

Trust-Based Disagreement

When there’s disagreement between words and behavior, believe the behavior. This is especially true when the words deny the behavior.

When there’s disagreement between the data and the decision, the data is innocent.

When there’s agreement that there’s insufficient data but a decision must be made, there should be no disagreement that the decision is judgment-based.

When there’s disagreement on the fact that there’s no data to support the decision, that’s a problem.

When there’s disagreement on the path forward, it’s helpful to have agreement on the process to decide.

When there’s disagreement among professionals, there is no place for argument.

When there’s disagreement, there is respect for the individual and a healthy disrespect for the ideas.

When there’s disagreement, the decisions are better.

When there’s disagreement, there’s independent thinking.

When there’s disagreement, there is learning.

When there’s disagreement, there is vulnerability.

When there’s disagreement, there is courage.

When there’s disagreement, there is trust.

“Teamwork” by davis.steve32 is licensed under CC BY 2.0

What Good Coaches Do

Good coaches listen to you. They don’t judge, they just listen.

Good coaches listen to you. They don’t judge, they just listen.

Good coaches continually study the game. They do it in private, but they study.

Good coaches tell you that you can do better, and that, too, they do in private.

Good coaches pick you up off the floor. They know that getting knocked over is part of the game.

Good coaches never scream at you, but they will cry with you.

Good coaches never stop being your coach. Never.

Good coaches learn from you, and the best ones tell you when that happens.

Good coaches don’t compromise. Ever.

Good coaches have played the game and have made mistakes. That’s why they’re good coaches.

Good coaches do what’s in your best interest, not theirs.

Good coaches are sometimes wrong, and the best ones tell you when that happens.

Good coaches don’t care what other people think of them, but they care deeply about you.

Good coaches are prepared to be misunderstood, though it’s not their preference.

Good coaches let you bump your head or smash your knee, but, otherwise, they keep you safe.

Good coaches earn your trust.

Good coaches always believe you and perfectly comfortable disagreeing with you at the same time.

Good coaches know it’s always your choice, and they know that’s how deep learning happens.

Good coaches stick with you, unless you don’t do your part.

Good coaches don’t want credit. They want you to grow.

Good coaches don’t have a script. They create a custom training plan based on your needs.

Good coaches simplify things when it’s time, unless it’s time to make things complicated.

Good coaches aren’t always positive, but they are always truthful.

Good coaches are generous with their time.

Good coaches make a difference.

How To See What’s Missing

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

With one eye open and the other closed, you have no depth perception. With two eyes open, you see in three dimensions. This ability to see in three dimensions is possible because each eye sees from a unique perspective. The brain knits together the two unique perspectives so you can see the world as it is. Or, as your brain thinks it is, at least.

And the same can be said for an organization. When everyone sees things from a single perspective, the organization has no depth perception. But with at least two perspectives, the organization can better see things as they are. The problem is we’re not taught to see from unique perspectives.

With most presentations, the material is delivered from a single perspective with the intention of helping everyone see from that singular perspective. Because there’s no depth to the presentation, it looks the same whether you look at it with one eye or two. But with some training, you can learn how to see depth even when it has purposely been scraped away.

And it’s the same with reports, proposals, and plans. They are usually written from a single perspective with the objective of helping everyone reach a single conclusion. But with some practice, you can learn to see what’s missing to better see things as they are.

When you see what’s missing, you see things in stereo vision.

Here are some tips to help you see what’s missing. Try them out next time you watch a presentation or read a report, proposal, or plan.

When you see a WHAT, look for the missing WHY on the top and HOW on the bottom. Often, at least one slice of bread is missing from the why-what-how sandwich.

When you see a HOW, look for the missing WHO and WHEN. Usually, the bread or meat is missing from the how-who-when sandwich.

Here’s a rule to live by: Without finishing there can be no starting.

When you see a long list of new projects, tasks, or initiatives that will start next year, look for the missing list of activities that would have to stop in order for the new ones to start.

When you see lots of starting, you’ll see a lot of missing finishing.

When you see a proposal to demonstrate something for the first time or an initial pilot, look for the missing resources for the “then what” work. After the prototype is successful, then what? After the pilot is successful, then what? Look for the missing “then what” resources needed to scale the work. It won’t be there.

When you see a plan that requires new capabilities, look for the missing training plan that must be completed before the new work can be done well. And look for the missing budget that won’t be used to pay for the training plan that won’t happen.

When you see an increased output from a system, look for the missing investment needed to make it happen, the missing lead time to get approval for the missing investment, and the missing lead time to put things in place in time to achieve the increased output that won’t be realized.

When you see a completion date, look for the missing breakdown of the work content that wasn’t used to arbitrarily set the completion date that won’t be met.

When you see a cost reduction goal, look for the missing resources that won’t be freed up from other projects to do the cost reduction work that won’t get done.

It’s difficult to see what’s missing. I hope you find these tips helpful.

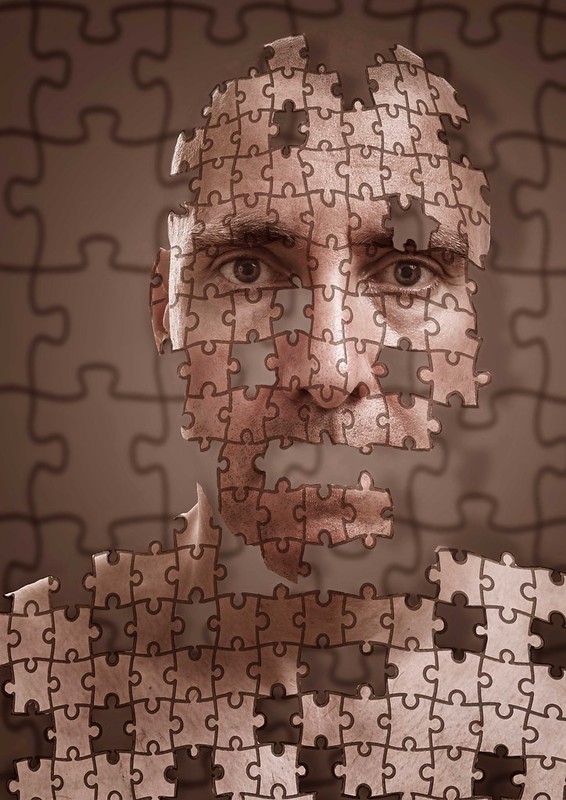

“missing pieces” by LeaESQUE is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

How To Grow Leaders

If you want to grow leaders, meet with them daily.

If you want to grow leaders, meet with them daily.

If you want to grow leaders, demand that they disagree with you.

If you want to grow leaders, help them with all facets of their lives.

If you want to grow leaders, there is no failure, there is only learning.

If you want to grow leaders, give them the best work.

If you want to grow leaders, protect them.

If you want to grow leaders, spend at least two years with them.

If you want to grow leaders, push them.

If you want to grow leaders, praise them.

If you want to grow leaders, get them comfortable with discomfort.

If you want to grow leaders, show them who you are.

If you want to grow leaders, demand that they use their judgment.

If you want to grow leaders, give them just a bit more than they can handle and help them handle it.

If you want to grow leaders, show emotion.

If you want to grow leaders, tell them the truth, even when it creates anxiety.

If you want to grow leaders, always be there for them.

If you want to grow leaders, pull a hamstring and make them present in your place.

If you want to grow leaders, be willing to compromise your career so their careers can blossom.

If you want to grow leaders, when you are on vacation tell everyone they are in charge.

If you want to grow leaders, let them chose between to two good options.

If you want to grow leaders, pay attention to them.

If you want to grow leaders, be consistent.

If you want to grow leaders, help them with their anxiety.

If you want to grow leaders, trust them.

If you want to grow leaders, demonstrate leadership.

“Mother duck and ducklings” by Tambako the Jaguar is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

The truth can set you free, but only if you tell it.

Your truth is what you see. Your truth is what you think. Your truth is what feel. Your truth is what you say. Your truth is what you do.

If you see something, say something.

If no one wants to hear it, that’s on them.

If your truth differs from common believe, I want to hear it.

If your truth differs from common believe and no one wants to hear it, that’s troubling.

If you don’t speak your truth, that’s on you.

If you speak it and they dismiss it, that’s on them.

Your truth is your truth, and no one can take that away from you.

When someone tries to take your truth from you, shame on them.

Your truth is your truth. Full stop.

And even if it turns out to be misaligned with how things are, it’s still your responsibility to tell it.

If your company makes it difficult for you to speak your truth, you’re still obliged to speak it.

If your company makes it difficult for you to speak your truth, they don’t value you.

When your truth turns out to be misaligned with how things are, thank you for telling it.

You’ve provided a valuable perspective that helped us see things more clearly.

If you’re striving for your next promotion, it can be difficult to speak your dissenting truth.

If it’s difficult to speak your dissenting truth, instead of promotion, think relocation.

If you feel you must yell your dissenting truth, you’re not confident in it.

If you’re confident in your truth and you still feel you must yell it, you have a bigger problem.

When you know your truth is standing on bedrock, there’s no need to argue.

When someone argues with your bedrock truth, that’s a problem for them.

If you can put your hand over mouth and point to your truth, you have bedrock truth.

When you write a report grounded in bedrock truth, it’s the same as putting your hand over your mouth and pointing to the truth.

If you speak your truth and it doesn’t bring about the change you want, sometimes that happens.

And sometimes it brings about its opposite.

Your truth doesn’t have to be right to be useful.

But for your truth to be useful, you must be uncompromising with it.

You don’t have to know why you believe your truth; you just have to believe it.

It’s not your responsibility to make others believe your truth; it’s your responsibility to tell it.

When your truth contradicts success, expect dismissal and disbelief.

When your truth meets with dismissal and disbelief, you may be onto something.

Tomorrow’s truth will likely be different than today’s.

But you don’t have a responsibility to be consistent; you have a responsibility to the truth.

image credit — “the eyes of truth r always watching u” by TheAlieness GiselaGiardino²³ is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

Without a problem there can be no progress.

Without a problem, there can be no progress.

And only after there’s too much no progress is a problem is created.

And once the problem is created, there can be progress.

When you know there’s a problem just over the horizon, you have a problem.

Your problem is that no one else sees the future problem, so they don’t have a problem.

And because they have no problem, there can be no progress.

Progress starts only after the calendar catches up to the problem.

When someone doesn’t think they have a problem, they have two problems.

Their first problem is the one they don’t see, and their second is that they don’t see it.

But before they can solve the first problem, they must solve the second.

And that’s usually a problem.

When someone hands you their problem, that’s a problem.

But if you don’t accept it, it’s still their problem.

And that’s a problem, for them.

When you try to solve every problem, that’s a problem.

Some problems aren’t worth solving.

And some don’t need to be solved yet.

And some solve themselves.

And some were never really problems at all.

When you don’t understand your problem, you have two problems.

Your first is the problem you have and your second is that you don’t know what your problem by name.

And you’ve got to solve the second before the first, which can be a problem.

With a big problem comes big attention. And that’s a problem.

With big attention comes a strong desire to demonstrate rapid progress. And that’s a problem.

And because progress comes slowly, fervent activity starts immediately. And that’s a problem.

And because there’s no time to waste, there’s no time to define the right problems to solve.

And there’s no bigger problem than solving the wrong problems.

Love Everyone and Tell the Truth

If you see someone doing something that’s not quite right, you have a choice – call them on their behavior or let it go.

If you see someone doing something that’s not quite right, you have a choice – call them on their behavior or let it go.

In general, I have found it’s more effective to ignore behavior you deem unskillful if you can. If no one will get hurt, say nothing. If it won’t start a trend, ignore it. And if it’s a one-time event, look the other way. If it won’t cause standardization on a worst practice, it never happened.

When you don’t give attention to other’s unskillful behavior, you don’t give it the energy it needs to happen again. Just as a plant dies when it’s not watered, unskillful behavior will wither on the vine if it’s ignored. Ignore it and it will die. But the real reason to ignore unskillful behavior is that it frees up time to amplify skillful behavior.

If you’re going to spend your energy doing anything, reinforce skillful behavior. When you see someone acting skillfully, call it out. In front of their peers, tell them what you liked and why you liked it. Tell them how their behavior will make a difference for the company. Say it in a way that others hear. Say it in a way that everyone knows this behavior is special. And if you want to guarantee that the behavior will happen again, send an email of praise to the boss of the person that did the behavior and copy them on the email. The power of sending an email of praise is undervalued by a factor of ten.

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, how do you feel?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, will you do more of that behavior or less?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, what do you think of the person that sent it?

When someone sends your boss an email that praises you for your behavior, will you do more of what the sender thinks important or less?

And now the hard part. When you see someone behaving unskillfully and that will damage your company’s brand, you must call them on their behavior. To have the most positive influence, give your feedback as soon as you see it. In a cause-and-effect way, the person learns that the unskillful behavior results in a private discussion on the negative impact of their behavior. There’s no question in their mind about why the private discussion happened and, because you suggested a more skillful approach, there’s clarity on how to behave next time. The first time you see the unskillful behavior, they deserve to be held accountable in private. They also deserve a clear explanation of the impacts of their behavior and a recipe to follow going forward.

And now the harder part. If, after the private explanation of the unskillful behavior that should stop and the skillful behavior should start, they repeat the unskillful behavior, you’ve got to escalate. Level 1 escalation is to hold a private session with the offender’s leader. This gives the direct leader a chance to intervene and reinforce how the behavior should change. This is a skillful escalation on your part.

And now the hardest part. If, after the private discussion with the direct leader, the unskillful behavior happens again, you’ve got to escalate. Remember, this unskillful behavior is so unskillful it will hurt the brand. It’s now time to transition from private accountability to public accountability. Yes, you’ve got to call out the unskillful behavior in front of everyone. This may seem harsh, but it’s not. They and their direct leader have earned every bit of the public truth-telling that will soon follow.

Now, before going public, it’s time to ask yourself two questions. Does this unskillful behavior rise to the level of neglect? And, does this unskillful behavior violate a first principle? Meaning, does the unskillful behavior undermine a fundamental, or foundational element, of how the work is done? Take your time with these questions, because the situation is about to get real. Really real. And really uncomfortable.

And if you answer yes to one of those two questions, you’ve earned the right to ask yourself a third. Have you reached bedrock? Meaning, your position grounded deeply in what you believe. Meaning, you’ve reached a threshold where things are non-negotiable. Meaning, no matter what the negative consequences to your career, you’re willing to stand tall and take the bullets. Because the bullets will fly.

If you’ve reached bedrock, call out the unskillful behavior publicly and vehemently. Show no weakness and give no ground. And when the push-back comes, double down. Stand on your bedrock, and tell the truth. Be effective, and tell the truth. As Ram Dass said, love everyone and tell the truth.

If you want to make a difference, amplify skillful behavior. Send emails of praise. And if that doesn’t work, send more emails of praise. Praise publicly and praise vehemently. Pour gasoline on the fire. And ignore unskillful behavior, when you can.

And when you can’t ignore the unskillful behavior, before going public make sure the behavior violates a first principle. And make sure you’re standing on bedrock. And once you pass those tests, love everyone and tell the truth.

Image credit — RamDass.org

The Toughest Word to Say

As the world becomes more connected, it becomes smaller. And as it becomes smaller, competition becomes more severe. And as competition increases, work becomes more stressful. We live in a world where workloads increase, timelines get pulled in, metrics multiply and “accountability” is always the word of the day. And in these trying times, the most important word to say is also the toughest.

As the world becomes more connected, it becomes smaller. And as it becomes smaller, competition becomes more severe. And as competition increases, work becomes more stressful. We live in a world where workloads increase, timelines get pulled in, metrics multiply and “accountability” is always the word of the day. And in these trying times, the most important word to say is also the toughest.

When your plate is full and someone tries to pile on more work, what’s the toughest word to say?

When the project is late and you’re told to pull in the schedule and you don’t get any more resources, what’s the toughest word to say?

When the technology you’re trying to develop is new-to-world and you’re told you must have it ready in three months, what’s the toughest word to say?

When another team can’t fill an open position and they ask you to fill in temporarily while you do your regular job, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re asked to do something that will increase sales numbers this quarter at the expense of someone else’s sales next quarter, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re told to use a best practice that isn’t best for the situation at hand, what’s the toughest word to say?

When you’re told to do something and how to do it, what’s the toughest word to say?

When your boss asks you something that you know is clearly their responsibility, what’s the toughest word to say?

Sometimes the toughest word is the right word.

Image credit –Noirathse’s Eye

When The Wheels Fall Off

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When your most important product development project is a year behind schedule (and the schedule has been revved three times), who would you call to get the project back on track?

When the project’s unrealistic cost constraints wall of the design space where the solution resides, who would you call to open up the higher-cost design space?

When the project team has tried and failed to figure out the root cause of the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of it?

And when you bring in the regular experts and they, too, try and fail to fix the problem, who would you call to get to the bottom of getting to the bottom of it?

When marketing won’t relax the specification and engineering doesn’t know how to meet it, who would you call to end the sword fight?

When engineering requires geometry that can only be made by a process that manufacturing doesn’t like and neither side will give ground, who would you call to converge on a solution?

When all your best practices haven’t worked, who would you call to invent a novel practice to right the ship?

When the wheels fall off, you need to know who to call.

If you have someone to call, don’t wait until the wheels fall off to call them. And if you have no one to call, call me.

Image credit — Jason Lawrence

Two Questions to Grow Your Business

Two important questions to help you grow your business:

Two important questions to help you grow your business:

- Is the problem worth solving?

- When do you want to learn it’s not worth solving?

No one in your company can tell you if the problem is worth solving, not even the CEO. Only the customer can tell you if the problem is worth solving. If potential customers don’t think they have the problem you want to solve, they won’t pay you if you solve it. And if potential customers do have the problem but it’s not that important, they won’t pay you enough to make your solution profitable.

A problem is worth solving only when customers are willing to pay more than the cost of your solution.

Solving a problem requires a good team and the time and money to run the project. Project teams can be large and projects can run for months or years. And projects require budgets to buy the necessary supplies, tools, and infrastructure. In short, solving problems is expensive business.

It’s pretty clear that it’s far more profitable to learn a problem is not worth solving BEFORE incurring the expense to solve it. But, that’s not what we do. In a ready-fire-aim way, we solve the problem of our choosing and try to sell the solution.

If there’s one thing to learn, it’s how to verify the customer is willing to pay for your solution before incurring the cost to create it.

Image credit — Milos Milosevic

The Most Powerful Question

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Artificial intelligence, 3D printing, robotics, autonomous cars – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

Creativity, innovation and continuous improvement – what do they have in common? In a word – learning.

And what about lifelong personal development? Yup – learning.

Learning results when a system behaves differently than your mental model. And there four ways make a system behave differently. First, give new inputs to an existing system. Second, exercise an existing system in a new way (for example, slow it down or speed it up.) Third, modify elements of the existing system. And fourth, create a new system. Simply put, if you want a system to behave differently, you’ve got to change something. But if you want to learn, the system must respond differently than you predict.

If a new system performs exactly like you expect, it isn’t a new system. You’re not trying hard enough.

When your prediction is different than how the system actually behaves, that is called error. Your mental model was wrong and now, based on the new test results, it’s less wrong. From a learning perspective, that’s progress. But when companies want predictable results delivered on a predictable timeline, error is the last thing they want. Think about how crazy that is. A company wants predictable progress but rejects the very thing that generates the learning. Without error there can be no learning.

If you don’t predict the results before you run the test, there can be no learning.

It’s exciting to create a new system and put it through its paces. But it’s not real progress – it’s just activity. The valuable part, the progress part, comes only when you have the discipline to write down what you think will happen before you run the test. It’s not glamorous, but without prediction there can be no error.

If there is no trial, there can be no error. And without error, there can be no learning.

Let’s face it, companies don’t make it easy for people to try new things. People don’t try new things because they are afraid to be judged negatively if it “doesn’t work.” But what does it mean when something doesn’t work? It means the response of the new system is different than predicted. And you know what that’s called, right? It’s called learning.

When people are afraid to try new things, they are afraid to learn.

We have a language problem that we must all work to change. When you hear, “That didn’t work.”, say “Wow, that’s great learning.” When teams are told projects must be “on time, on spec and on budget”, ask the question, “Doesn’t that mean we don’t want them to learn?”

But, the whole dynamic can change with this one simple question – “What did you learn?” At every meeting, ask “What did you learn?” At every design review, ask “What did you learn?” At every lunch, ask “What did you learn?” Any time you interact with someone you care about, find a way to ask, “What did you learn?”

And by asking this simple question, the learning will take care of itself.

Image credit m.shattock

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski