DFA and Lean – A Most Powerful One-Two Punch

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Lean is all about parts. Don’t think so? What do your manufacturing processes make? Parts. What do your suppliers ship you? Parts. What do you put into inventory? Parts. What do your shelves hold? Parts. What is your supply chain all about? Parts.

Still not convinced parts are the key? Take a look at the seven wastes and add “of parts” to the end of each one. Here is what it looks like:

- Waste of overproduction (of parts)

- Waste of time on hand – waiting (for parts)

- Waste in transportation (of parts)

- Waste of processing itself (of parts)

- Waste of stock on hand – inventory (of parts)

- Waste of movement (from parts)

- Waste of making defective products (made of parts)

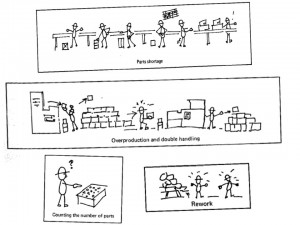

And look at Suzaki’s cartoons. (Click them to enlarge.) What do you see? Parts.

Take out the parts and the waste is not reduced, it’s eliminated. Let’s do a thought experiment, and pretend your product had 50% fewer parts. (I know it’s a stretch.) What would your factory look like? How about your supply chain? There would be: fewer parts to ship, fewer to receive, fewer to move, fewer to store, fewer to handle, fewer opportunities to wait for late parts, and fewer opportunities for incorrect assembly. Loosen your thinking a bit more, and the benefits broaden: fewer suppliers, fewer supplier qualifications, fewer late payments; fewer supplier quality issues, and fewer expensive black belt projects. Most importantly, however, may be the reduction in the transactions, e.g., work in process tracking, labor reporting, material cost tracking, inventory control and valuation, BOMs, routings, backflushing, work orders, and engineering changes.

However, there is a big problem with the thought experiment — there is no one to design out the parts. Since company leadership does not thrust greatness on the design community, design engineers do not have to participate in lean. No one makes them do DFA-driven part count reduction to compliment lean. Don’t think you need the design community? Ask your best manufacturing engineer to write an engineering change to eliminates parts, and see where it goes — nowhere. No design engineer, no design change. No design change, no part elimination.

It’s staggering to think of the savings that would be achieved with the powerful pairing of DFA and lean. It would go like this: The design community would create a low waste design on which the lean community would squeeze out the remaining waste. It’s like the thought experiment; a new product with 50% fewer parts is given to the lean folks, and they lean out the low waste value stream from there. DFA and lean make such a powerful one-two punch because they hit both sides of the waste equation.

DFA eliminates parts, and lean reduces waste from the ones that remain.

There are no technical reasons that prevent DFA and lean from being done together, but there are real failure modes that get in the way. The failure modes are emotional, organizational, and cultural in nature, and are all about people. For example, shared responsibility for design and manufacturing typically resides in the organizational stratosphere – above the VP or Senior VP levels. And because of the failure modes’ nature (organizational, cultural), the countermeasures are largely company-specific.

What’s in the way of your company making the DFA/lean thought experiment a reality?

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski

Absolutely…One of the biggest mistakes a engineering manufacturer can make is to release a design with the belief that Manufacturing will have to lean out their enterprise to make the venture profitable with the new design. I run into this every day, and I’ve heard it proclaimed right out loud. I shake my head.

The need for lean methodologies in the first place is based on waste. Without waste, lean really has no place to go (which would be great). Lean won’t fix an inefficient design either. When a new product is in the development / design stage, it’s a GREAT idea to have the seven wastes plastered right to the wall and in your face with a goal to see that none of them exist within the plans for production release.

The author is spot-on when he says DFA [and DFM] first, then lean out the production process to dial it in. DFMA means never having to say you’re sorry.

We have driven this point home with our Design Engineers to the point where they preach it to other new Design Engineers. I dont hear “buts its just one part” from our guys anymore. But it’s a constant fight to keep from slipping back to the old ways. Well written. Thanks.

As always, the points in your recent articles are well stated. DFMA and quality initiatives generally share a common impedance source. Despite the enormous impact potential of various front end DFMA and quality improvement tools available, there is seldom any glory and/or recognition for those who pursue them. Unfortunately this phenomenon is, as you state organizationally and culturally rooted…not only within an organization, but within us as Americans.

If you are the leader who skillfully negotiated an organization through the worst imaginable product quality disaster, you are immediately hailed as a hero. If you are the guy who made the worst imaginable product quality disaster never happen in the first place, no one notices. Not even a little. If you are the DFMA Design Engineer who made the offending product not exist in the first place such that a quality disaster wasn’t even possible, no one notices.

Our cultural reactions to tragedies, such as the recent one in Haiti are another example of this. We think of people who provide emergency medical assistance to folks in need as heroes. People who enforce building codes, install concrete rebar, or design sprinkler systems are not considered heroes. Building codes save more lives each year than firefighters.

DFMA is fantastically powerful. The group doing it won’t receive much gratitude. American executive leaders, or those pursuing these positions gravitate toward short term highly visible activities that get them noticed…even if they are frivolous. Unfortunately it’s no surprise DFMA isn’t everywhere. It needs to be if American manufacturing wants to compete globally.

Didn’t Toyoda say something about western engineers obviously being scared of the plant, as they never went there?

Produce centric teams instead of function centric departments help people remember who the customer is.

“A bad company cannot make a good product”