How To Create Clarity

Take a position. People will have to reconcile their thinking with yours and, together, the crew will deepen the collective understanding.

Take a position. People will have to reconcile their thinking with yours and, together, the crew will deepen the collective understanding.

Take an opposite position. Announce you are running a thought experiment and take a position that is opposite of the prevailing theory. Make it good. Make it deep. Do it for real. The prevailing theory will be strengthened, adapted, or discarded, and everything will be better for it.

Take an opposite position to your own prevailing wisdom. If there’s no one to play with, repeat the previous exercise with yourself. Give yourself the business. I bet you’ll teach yourself something and you’ll have better clarity on what you know and what you don’t.

Challenge someone’s best thinking. Announce you want to help them sharpen their thinking. Ask them why they think as they do. When they answer, ask them “why?” again. Repeat this process until you’ve asked “why?” five times. This process is aptly named The Five Whys. If they don’t feel uncomfortable, you’re doing it wrong.

Draw a picture. Announce that you want to help solve the problem. Ask “What’s the problem?” Then, draw a picture of the problem and show it to the crew. It won’t be right, but that’s okay. Ask them to fix the drawing so it captures the problem. Repeat the process until the picture looks like the problem. From there, the solving will come easily. Here’s an old blog post from 2013 with a simple “problem defining” template — How Engineers Create New Markets and another from 2017 that describes how to sketch a problem — See Differently To Solve Differently.

Make a Map. Check out these two blog posts — To Make Progress, Make a Map (2023) and The Half-Life of Our Maps (2014).

I think it’s better to be clear than correct. Clarity brings contrast; contrast creates conversation; and conversation begets understanding.

Clarity is king.

Image credit – Natashi Jay

What race are you running?

The marathon is a two-to-three-hour race. The training plan is specialized and designed to get the athletes ready to run twenty-six miles. And the marathon runners are lean and light because the physics of their event demands it.

The marathon is a two-to-three-hour race. The training plan is specialized and designed to get the athletes ready to run twenty-six miles. And the marathon runners are lean and light because the physics of their event demands it.

The 100-meter sprint is a sub-ten-second race. The training plan develops explosive power to accelerate quickly and strength to hold on for the last twenty meters. Sprinters are muscled all over – shoulders, chest, glutes, quads, and calves – because that’s what’s required to win their event.

The decathlon is a multi-day event. The training plan includes jumping, vaulting, throwing, sprinting, and distance running. Decathletes are strong, nimble, fast, robust, and multi-skilled because they compete in a wide range of events. They do it all, and they do it on their own. They are often called the best track athletes because they are highly capable in ten diverse events. But they cannot outlast a marathon runner or out-accelerate a sprinter.

The 4 X 400-meter relay is a three-plus-minute race in which each of the four teammates runs 400 meters carrying a baton and passes it to their teammate. They train as a team for their specific distance and build the right amount of strength. They are muscled all over, but a little less so than the sprinters. And they must work together with their teammates to time and coordinate a high-speed baton pass within the pass zone. If they drop the baton, they all lose, so teamwork is a must.

Some questions for you.

What are you built for?

Does your sport fit you?

Do you have a good training plan?

How much time will you spend on your training?

Do you want to work on one thing or ten?

Do you want to run solo or with a relay team?

Image credit – Steve Austin

Would you rather have too many projects or too many resources?

When you have more projects than people, you have far more activity but far less progress.

When you have more projects than people, you have far more activity but far less progress.

Pro Tip: Activity doesn’t pay the bills. Progress does.

Would you rather make lightning progress on two projects or tortoise progress on four? I prefer lightning.

But isn’t four projects better than two? It is, if you get compensated for the number of active projects. But it’s not, if you get compensated for finishing projects.

Pro tip: There’s no partial credit for a project that’s less than 100% done.

But how to protect your resources from four projects when you have the resources to deliver on two? This is not a complicated answer: block the extra project from entering the pipeline until you finish one.

Pro Tip: Finish one before you start one, not the other way around.

But what about the efficiency that comes from shared resources that can be spread over four projects? Don Reintertsen would say “Shared resources create waiting and waiting is the enemy.” I agree with Don, but I think his language is too reserved. I say “If you’re focused on the efficiency that comes from shared resources, you don’t know what you’re doing.”

Pro Tip: Waiting kills progress. Don’t do it.

Here’s a process to consider.

- Define the resources you have on hand to work on projects.

- Choose the most important project and fully staff the project. If the project is fully staffed, start the project.

- Define the remaining unallocated resources.

- Choose the next most important project and fully staff the project. If the project is fully staffed, start the project. If the project is not fully staffed, don’t start a project until you finish one, or you can hire the incremental resources to fully staff a project.

- Repeat.

Image credit – KIUKO (Elephant Tortoise)

How To Create The Conditions For Good Things To Happen

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Reduce the energy cost of virtue so it’s less than the energy cost of sin. (Dave Snowden)

Said another way – make it easy to do the right thing.

Don’t push through. Move obstacles out of the way.

Don’t tell people about their problem. Ask people about their problem.

Try small experiments and do more of what works and less of what doesn’t.

Don’t tell people they have a problem. Volunteer to help them.

Instead of Ready, Fire, Aim, try Ready, Aim, Fire.

Before trying to improve things, define the system as it is.

When two competing theories cause disagreement, agree to try both.

Slow down to go faster.

Say no so you can say yes.

Give praise in public and give criticism in private.

Say nothing negative unless you’ve exhausted all other possibilities.

Build trust BEFORE you need it.

These are good ways to create the conditions for good things to happen.

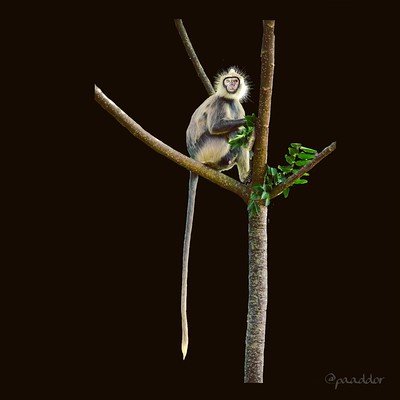

Image credit — Peter Addor – The monkey that makes a monkey of us.

It’s All About Your Questions

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to test others?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to test others?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question to help others think differently?

When you know the answer, do you keep quiet because it’s not the right time for a question?

When you know the answer, do you ask the question even though it’s not the right time for a question?

What does that say about you?

When you think you know the answer, do you ask the question to seek the right answer?

When you think you know the answer, do you ask the question and risk looking like you don’t know?

When you think you know the answer, do you keep quiet for reasons you don’t understand?

What does that say about you?

When you don’t know the answer, do you ask in public to solicit diverse perspectives?

When you don’t know the answer, do you ask someone you trust in private?

When you don’t know the answer, do you throw away the question?

What does that say about you?

When you’re asked a question that doesn’t need to be answered yet, do you ask, “Do we need to know that yet?”

When you’re asked a question that cannot be answered yet, do you ask, “Can we know that yet?”

When you’re asked a question that is too costly to answer, do you ask, “Do we have enough time and money to know that?”

Do you have the courage to ask those three questions?

What does that say about you?

Image credit – Tambako The Jaguar

Small Improvements Are Beautiful

When the cost of the experiment is small, the downside of its potential failure is also small.

When the cost of the experiment is small, the downside of its potential failure is also small.

Small improvements cost little and can be implemented quickly.

Small improvements make a difference.

If the transformational improvement never sees the light of day because it costs too much to implement, its realized value is less than the smallest improvement that was implemented.

When a small experiment does not go as planned, the learning can be significant (and fast).

Small experiments are funded by small investments that don’t require approval. Don’t seek approval. Run the experiment.

The second small improvement stands on the shoulders of the first one

If the improvement is never implemented, it’s not an improvement.

Small improvements can be tested under the radar. When they work well, give the credit to someone who deserves it. When they go poorly, try something else.

Like ants, small improvements gang up to make a real difference.

Once a small improvement is implemented, it stays implemented. Like a one-way ratchet, there’s no backsliding.

Small improvements add up over time, but only if you bring them to life.

When it comes to improvements, small is beautiful.

Image credit — Jim Roberts – Papa I’m only a little sparrow

Do you have what it takes?

When there’s no light, no one can see.

When there’s no light, no one can see.

When no one can see, what do you do?

Can you be a source of light?

Do you care enough to do that?

When there’s too much input, focus is difficult.

When there’s a shortfall of focus, what do you do?

Can you dampen things and bring focus?

Do you have the emotional energy for that?

When there’s too much emotional stress, people become scattered.

When scattering comes, what do you do?

Can you pull people together?

Do you take responsibility and do that?

When the old recipe no longer works, people pucker.

When there is puckering, what do you do?

Can you recognize the pucker and plot a new course?

Do you bring the energy for that?

When there is support and guidance, people do great work.

When they did great work, did you play a role?

When they did great work, did you tell them?

Do you have the mojo to do it again?

When there is air cover and protection, people take risks.

When they took a risk, did you create the causes and conditions?

When they took a risk, did you praise them in public?

Do you have what it takes to praise in public?

When there is a teacher and time to learn, everything gets better.

When they learned, were you the teacher?

When they learned, did you create the opportunity for them to demonstrate their learning?

Do you have what it takes to teach and create the causes and conditions for learning to come more easily?

Image credit — Darren Flinders, Flamborough Lighthouse

Projects generate progress.

Companies make progress through projects.

Companies make progress through projects.

Projects have objectives that are defined by the company’s growth or improvement objectives.

Projects have quantifiable goals that are, hopefully, time-bound.

Projects require resources, and those resources limit the number of projects that are completed.

Projects are run with the resources allocated, not with the resources we want to allocate.

Projects have timelines that are governed by the work content, novelty, and resources.

Project timelines cannot violate the governing constraints of work content, novelty, and resources.

Projects have project managers, or they’re not projects.

Projects can be accelerated by eliminating waiting. To find the waiting, look for the work queued up in front of the bottleneck resources. Those resources are usually resources that support multiple projects (shared resources). When it comes to waiting, shared resources are almost always the culprit.

Projects have a critical path. A one-day delay (waiting) on the critical path delays project completion by a day. That’s how you know it’s the critical path.

If you don’t know the project’s critical path, you don’t know much.

When it comes to projects, effectiveness is far more important than efficiency, yet we fixate on efficiency. Would you rather run the wrong project efficiently (ineffective) or run the right project inefficiently (effective)?

Regardless of the business you’re in, it’s all about the projects.

Image credit — State Library of South Australia

Things aren’t good or bad. We make them that way.

More isn’t better, it’s just more. What makes it better is how it compares to the expectations we set.

More isn’t better, it’s just more. What makes it better is how it compares to the expectations we set.

Less isn’t worse, it’s just less. What makes it work is how we compare it to what we want.

Enough isn’t enough until we decide it is.

We forget what we have until we don’t have it.

Our health isn’t bad until we can’t do what we want to do. But don’t we decide what we want to do?

Activities aren’t fun unless the experiences exceed our minimum level of enjoyment. But aren’t we the ones who define that threshold?

When we look back at last year, we will have more of some things and less of others. None of the situations are good or bad, but we will make them that way by comparing what happened with what we wanted, what we expected, or the thresholds society sets for us. We will decide what’s good and what’s bad. We will define our level of happiness.

When we look forward to next year, we will set expectations or goals to have more of some things and less of others. We will define those thresholds and establish the criteria for good/bad. And at the end of the year, we will compare what happened against our self-defined thresholds. We will be responsible for our happiness.

Things happened last year. They were not good or bad. They just were. We can’t change what happened, but we can change how we feel about what happened. At the end of the year, may we be aware that we set our good/bad thresholds for the year. And may we remember that we defined our thresholds somewhat arbitrarily, and we can reset them along the way.

Things will happen next year. They will not be good or bad. They will just be. We won’t have infinite control over what happens, but we can control our good/bad thresholds. At the start of next year, may we set our good/bad thresholds skillfully.

Image credit — Ajay Goel

Elevate the Holiday Season by Understanding WHY

What is this all about?

What is this all about?

What is the reason you do what you do? What’s your WHY behind the WHAT?

When you don’t do what you said you’d do, what’s the reason? And what does that say about you?

If the reason is right, I think it can be okay NOT to do something you said you’d do. But I try to set a high bar on this one.

When things get tough, what gets you to push through? For me, it’s about doing something for the people I care about.

When things go well, what causes you to give credit to others? For me, it’s about building momentum and helping people understand the special things they did to make it happen.

Why do you show up? When you ask yourself, do you have an answer?

How do you show up for? And the more difficult question – WHY?

When is it okay to be compliant in a minimum energy way? And how do you decide that’s okay?

When do you decide to apply your whole self to something that others think is misaligned with the charter? I think this says a lot about a person.

What are you willing to do even though you know you’ll be judged negatively for doing it? I’m often unsure why to do it, but I’m sure it’s the right thing to do. I don’t know what that says about me, but I’m okay with it.

To me, the WHY is far more important than the WHAT. The WHY explains things. The WHY tells the story. The WHY gives guidance on what will happen next time.

When you do something happen that’s out of the ordinary (a WHAT), I suggest you try to figure out the WHY. I have found that some seemingly nonsensical WHATs make a lot of sense when you understand the WHY underpinning the WHAT.

And during this holiday season, may you give people the benefit of the doubt on their WHATs, and take the time to understand their highly personal WHYs. That can make for a happier holiday season for all.

Image credit — Christopher Henry

How To Battle Emotional Stress

Emotional stress is similar to physical stress. Both are exhausting, depleting, distracting, and physically limiting. But with physical stress, the cause is clear; the cause of emotional stress can be invisible.

Emotional stress is similar to physical stress. Both are exhausting, depleting, distracting, and physically limiting. But with physical stress, the cause is clear; the cause of emotional stress can be invisible.

When you go to the gym and lift weights, the physical stress is clear. You can see the dumbbells move up and down; you can see your arms connected to the dumbbells as they move; and you can feel your muscles do their work. And after the workout, you know why you are tired, and you expect to feel sore the next day. Action-response. Input-output. Cause-effect.

When you go into the office and do your work, the emotional stress is less clear. You can see what must be done, but sometimes you are too busy to do it. You want to do it, but you cannot. And that mismatch between what you want and your inability to get it done creates emotional stress. You take no action, yet you still experience emotional stress. There is input but no output, yet there is stress. There is a cause you cannot affect, and you create emotional stress.

With physical stress, you generate stress through movement. With emotional stress, you can generate stress through a lack of movement or progress.

If you forgot you went to the gym yesterday and woke up this morning tired and with sore muscles, you’d be confused about what was going on in your body. Why am I sore? Why am I tired? I don’t get it. What’s wrong with me? But, in truth, there would be nothing wrong with you. There would be a reason for your bodily tiredness and soreness, but the cause would be invisible to you. Emotional stress is like this.

Many situations can cause you to create emotional stress. For example, emotional stress can come when things don’t go as planned, when someone treats you poorly, or when the outcome is different than your expectations. But because your day is busy and you are juggling projects, the cause of your stress can be less than obvious. You feel more tired than you should, but you don’t know why. You are irritable, but you don’t understand what’s behind it. And maybe you ask – What’s wrong with me? And maybe you’re confused, and you judge yourself negatively.

I think we can reduce our emotional stress if we are more aware of its causes. What if we saw our workplaces as a gym? What if we saw our workdays as physical workouts? We could label our meetings as emotional bench press exercises. We could declare our conversations are dumbbell curls. We could see our deep work as an aerobic activity.

Why not give it a try? You may be more relaxed when you get home after your eight-hour “workout.”

Image credit — Joachim Dobler

Mike Shipulski

Mike Shipulski